Kiezdeutsch: Ein neuer Dialekt entsteht

by Heike Wiese

Reviewed by Lindsay Preseau

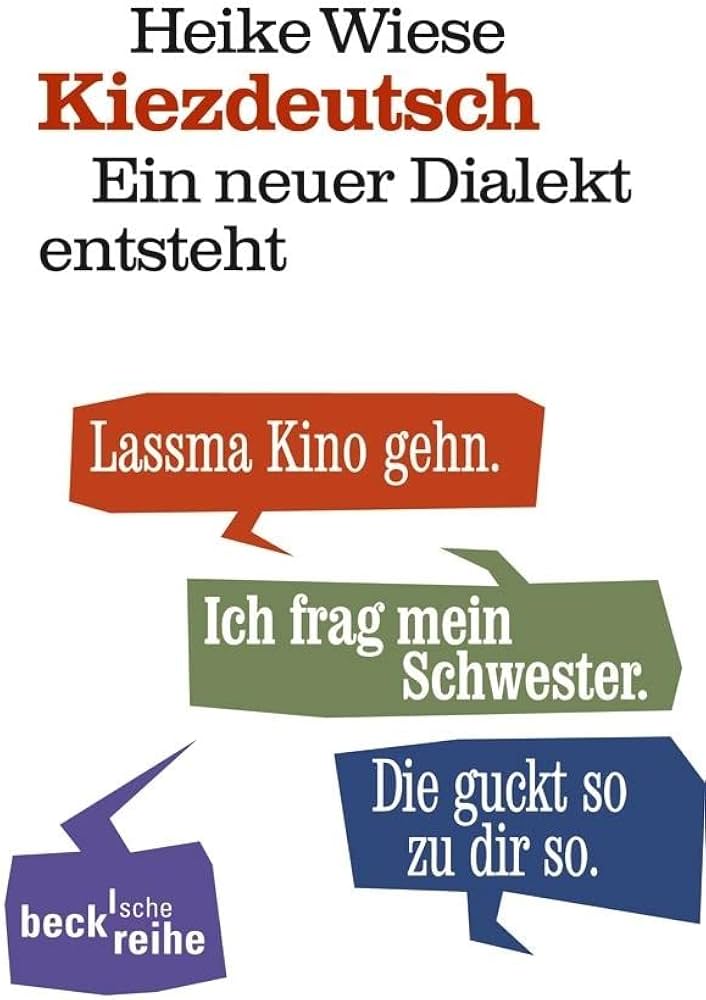

Heike Wiese, Kiezdeutsch: Ein neuer Dialekt entsteht. München: Beck, 2012. Pp. 280. Paper, 12,95 €.

Linguist Heike Wiese has been researching the German urban youth dialect called Kiezdeutsch (literally translated as ‘neighborhood German,’ and reminiscent of English terms such as ‘hood talk’) with her colleagues at University of Potsdam since 2006. Her diverse work on the syntactic, information-structural, lexical, and sociolinguistic features of Kiezdeutsch has led her to propose that Kiezdeutsch is best understood not as a traditional ethnolect, but as a “multiethnolect” spoken by speakers of various ethnic and immigration backgrounds. Kiezdeutsch, she argues, nonetheless shows systematic grammatical regularities, many of which are typical of Germanic languages. Though Kiezdeutsch: Ein neuer Dialekt ensteht presents Wiese’s findings to a non-academic audience, it provides a comprehensive overview of her research on Kiezdeutsch, and, more importantly, it serves as an effective instrument of education and advocacy on behalf of Kiezdeutsch in the public discourse.

Part One of Kiezdeutsch, which gives a linguistic account of Kiezdeutsch as a dialect of German, begins by introducing the dialect as a phenomenon of a multilingual speech community. Wiese deconstructs the popular assumption that Kiezdeutsch is a mixed Turkish-German and/or Arabic-German variety, arguing further that the specific non-German languages spoken by Kiezdeutsch speakers have had little effect on the linguistic features of the dialect itself. Instead, Wiese argues that “non-standard” variations in Kiezdeutsch largely stem from the fact that its multilingual speakers are particularly linguistically flexible and open to accepting regional variations or changes already in progress in the German language. While Wiese observes that Kiezdeutsch was born among youth in multilingual urban environments, she emphasizes that many of the “non-standard” features of Kiezdeutsch are common in regional dialects of German. Furthermore, she argues that the features of Kiezdeutsch which do represent foreign borrowings are mainly lexical, are integrated into German phonology, and are used by Kiezdeutsch speakers who are not necessarily competent in the languages from which forms are borrowed. Finally, Wiese claims that there are parallels to Kiezdeutsch in other Germanic languages in Europe such as Swedish and English. These dialects show lexical, phonological, and grammatical similarities to Kiezdeutsch, and can all be similarly characterized as “multiethnolects” emerging from multilingual urban youth populations.

Chapter Three gives specific examples of characteristic grammatical innovations of Kiezdeutsch, including preposition- and article-dropping, shortening and deletion of inflectional endings and function words, particalization, light-verb constructions, and word order variation. Wiese argues that each innovation supports her previous arguments that innovations in Kiezdeutsch are mainly typical “Germanic” innovations rather than markers of influence from immigrant languages, and that none of the innovations represent a “reduction” of German grammar. This chapter is prefaced as being an optional read for the grammar-shy. However, the examples should be accessible even to those without knowledge of linguistics or German grammar, and will likely be more convincing than Wiese’s claims alone, especially to non-linguists unfamiliar with the study of language change.

Part Two of Kiezdeutsch departs from the more technical discussion of the grammatical features of Kiezdeutsch and approaches Kiezdeutsch as a dialect of German from a sociolinguistic perspective. In the style of Laurie Bauer and Peter Trudgill’s popular linguistics book Language Myths, Wiese refutes three popular myths about Kiezdeutsch that regularly circulate in the media and public discourse. First, she argues against the belief that Kiezdeutsch is broken German or immigrants’ failed attempt at speaking German. This myth, which arose in 1990s media discourse about so-called ‘Kanak-Sprak,’ relies on a misunderstanding of the grammatical innovations of Kiezdeutsch as reductive and exemplifies typical devaluation of minority dialects and their speakers by prestige-dialect speakers. Similarly, Wiese argues that it is a myth that Kiezdeutsch signifies poor integration of immigrants into German society. She points out that not only is Kiezdeutsch spoken by non-immigrants, but it is a social register used by urban youth, and that speakers are thus generally also proficient in standard German and/or regional dialects of German. Finally, Wiese tackles the myth that Kiezdeutsch is a threat to the German language that constitutes a fatal simplification of German grammar or a process of German changing into Turkish. She claims that this argument often coincides with general fears about the alleged insecurity of modern German social order in the face of immigration and is part of a more general trend of anti-Islamic sentiment and moral panic. Moreover, she points out that the number of first- and second-language speakers of German and the status of German as a majority language is simply not consistent with the greater myth of German as an endangered language.

It is not until the conclusion of the book that Wiese presents solutions for the stigmatization and devaluation of Kiezdeutsch. Wiese seems to believe that the responsibility lies mainly with the school system, pointing out the disparities in scholastic success among immigrant children in the German schools. The solutions, she says, include recognizing varieties like Kiezdeutsch as legitimate dialects rather than “incorrect” forms of German. Standard German, she continues, should be taught from a young age so that all children, not just those who speak near-standard dialects at home, have access to the standard. In terms of putting such solutions into practice, Wiese introduces her online Kiezdeutsch Infoportal project, which provides activities, sound clips, and information for teaching about Kiezdeutsch in the classroom. Additionally, the book ends with a Kiezdeutsch quiz and glossary as a fitting culmination to the book’s goal of presenting Kiezdeutsch as a systematically-regular dialect of German. However, in her discussion of the future of Kiezdeutsch in the last pages of her book, Wiese hints that such destigmatization may already be occurring “naturally.” She predicts that many features of Kiezdeutsch will continue to be carried over into areas of language use outside of casual youth language, which may play a role in legitimatizing Kiezdeutsch as a dialect of German.

For linguists, much of the sociolinguistic discussion in Kiezdeutsch, particularly in the second half of the book, will likely not be particularly enlightening or informative. However, considering the book is intended as popular science, the first half of the book presents a surprisingly broad overview of Wiese and her colleagues’ work on the grammar of Kiezdeutsch. Furthermore, the argument that Kiezdeutsch is better understood as a typical dialect of German than as “Turkish-German” or a specialized ethnolect is, in fact, a new and provocative argument in the field of Germanic linguistics in light of previous scholarship on these dialects. Prior to Wiese and her colleague’s work, such dialects were often referred to in literature using terms such as “ethnolect” or, more specifically, “Kanak-Sprak,” both of which distance Kiezdeutsch from the German language and emphasize a foreignness and/or heterogeneity of its speakers that Wiese argues does not exist. The claim that Kiezdeutsch is best viewed as a “multiethnolect” will no doubt whet linguists’ appetites for a more in-depth linguistic substantiation of this claim, which can be found in the article “Kiezdeutsch as a multiethnolect,” published by Wiese and her colleagues in 2012.

As a popular linguistics books for a more general audience, Kiezdeutsch succeeds in being accessible and entertaining and, perhaps more importantly, provides a refreshing voice of reason in German popular culture. Using examples from internet forums and popular websites like Urban Dictionary alongside data from linguistic corpora and experiments, Wiese maintains a light, entertaining tone without overgeneralizing, oversimplifying, or sacrificing academic rigor. The press coverage that the book has received in German and English media alike (in The Economist, Der Spiegel, and FOCUS, for example) has clearly sparked a more informed public conversation about Kiezdeutsch (compare these articles, for example, with a 2007 Welt article bemoaning the fact that German is morphing into Turkish through “reductive” changes to the German lexicon and grammar).

Though some may find the book’s brief proposed solutions to the stigmatization of Kiezdeutsch unsatisfying, it should be clear to linguists that Kiezdeutsch is perhaps in and of itself one of the most effective solutions. Kiezdeutsch is an excellent example of effective education and awareness through popular science, as evidenced by its reception in the German media. Furthermore, the book fills a nearly empty gap in popular German literature on language, which has long lacked the voices of trained linguists in the style of English-language linguist-authors such as Stephen Pinker and David Crystal. With the notable exception of linguist André Meinunger’s recent book Sick of Sick, a rebuttal of popular German language critic Bastian Sick’s prescriptivist claims, German popular literature on language has until recently consisted mainly of instructional grammars and book-length diatribes lamenting the fall of the German language. The fact that Kiezdeutsch is truly innovative in German popular literature is perhaps best illustrated in the irony of the advertisements printed in the back of Kiezdetusch for Lost in Laberland: Neuer Unsinn in der deutschen Sprache and Die 101 häufigsten Fehler im Deutschen. Kiezdeutsch is a prime example of the practical application of academic research, and, with any luck, will continue to spark new trends in media discussion of minority dialects and in popular German literature on language.

—Lindsay Preseau (University of California, Berkeley)