Ming Wong’s Imitations

Barbara Mennel

Abstract

The article “Ming Wong’s Imitations” analyzes the installation Life of Imitation, created by visual artist Ming Wong for the Singapore Pavilion at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009. Life of Imitation restages a key scene from Douglas Sirk’s 1959 melodrama Imitation of Life, in which the African American character Annie visits her daughter Sarah Jane who is passing as white. In Wong’s restaging three male actors from different ethnic groups in Singapore reenact the scene, but switch roles at every cut. The article traces the shifts from the original literary source, Fannie Hurst’s 1933 Imitation of Life to John M. Stahl’s 1934 film of the same title to Sirk’s version. Emphasizing melodrama’s organizing structure of “too late,” I show how Sirk shifted the melodramatic emphasis from the white mother/daughter pair’s romantic conflict to the African American mother/daughter pair’s racial conflict. Addressing the question whether such a shift implies a progressive politics, I turn to the contentious discussion of Sirk’s earlier film work in Weimar and Nazi Germany, pointing to ideological and formal continuities.

In contrast to these significant shifts in the different instantiations of the text, I propose that the different versions share the subordination and disavowal of ethnic difference in order to construct a racial binary, which then becomes the setting of the passing narrative organized around the ‘tragic mulatta’. I illustrate my argument with the instances of ethnic passing of the writers, directors, and actors involved in the different versions of the text. However, I also show the appeal of racial passing narratives can have for a gay camp imagination, identification, and appropriation. I conclude the article with a discussion of Wong’s double move in Life of Imitation of returning ethnic bodies that have been excised from the original diegesis to their significance and appropriating the gendered melodrama through cross-dressing. After a survey of the term “remediation” as it emerged from the discussion of new media, I show that Wong’s piece belongs to a group of works by visual artists who remake film in digital media in the environment of the art space. I conclude with reading the effect of rotating the actors at each cut, which does not subvert spatial and temporal continuity, but challenges spectators’ perception of ethnicity and gender, and produces unstable identities.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Angelica Fenner and Uli Linke for inviting me to the symposium “Contemporary (Re)Mediations of Race and Ethnicity in German Visual Cultures” at the University of Toronto and for their patience and sophistication in guiding this article to its current version. I would also like to acknowledge the scholarly generosity of Katrin Sieg, who introduced me to Ming Wong’s work some time ago, and Ming Wong and his gallerist Mathilda Legemah of carlier | gebauer in Berlin for sharing digital copies of Wong’s installation pieces. Finally, I would like to acknowledge Jeffrey S. Adler for introducing me to some of the research tools, Amy Ongiri for indulging my obsession with Imitation of Life, and Wayne Losano for editing an earlier version of this article. I also thank my colleague Theresa A. Antes for confirming my reading of the French article, the anonymous reviewer for incisive references and corrections that spared me minor embarrassments, and Erik Born for all his help.

Ming Wong’s Art of Imitation

Life of Imitation—the installation prepared by Singaporean performance and multi-media artist Ming Wong for his solo exhibition in the Singapore Pavilion at the 2009 Venice Biennale—restages a pivotal scene from Imitation of Life, Douglas Sirk’s famous 1959 Hollywood maternal melodrama, closely replicating its stage blocking of characters, dialogue, and shot composition.

Source: Ming Wong, Life of Imitation, 2009; two channel video installation

Courtesy: carlier | gebauer, Berlin and Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou

In Wong’s double projection, the three Singaporean actors Sebastian Tan, Moe Kasim, and Alle Majeed—each a member of one of the country’s dominant ethnic groups (Chinese, Malayan, and Indian)—systematically rotate through the female roles of the source material.1 In the key scene from Imitation of Life, the African American maid Annie Johnson, one of the two lead female characters, is visiting her light-skinned daughter Sarah Jane at her workplace in a Los Angeles nightclub. To pass as white, Sarah Jane had previously run away and renounced her mother, who was only able to track her down with the help of a private detective. After a confrontation between the two in a motel room, which ends in a tearful embrace, Sarah Jane’s friend (billed as “Showgirl”) happens to enter and becomes a witness to Sarah Jane’s racial passing, which her mother reinforces by pretending to be her former mammy.

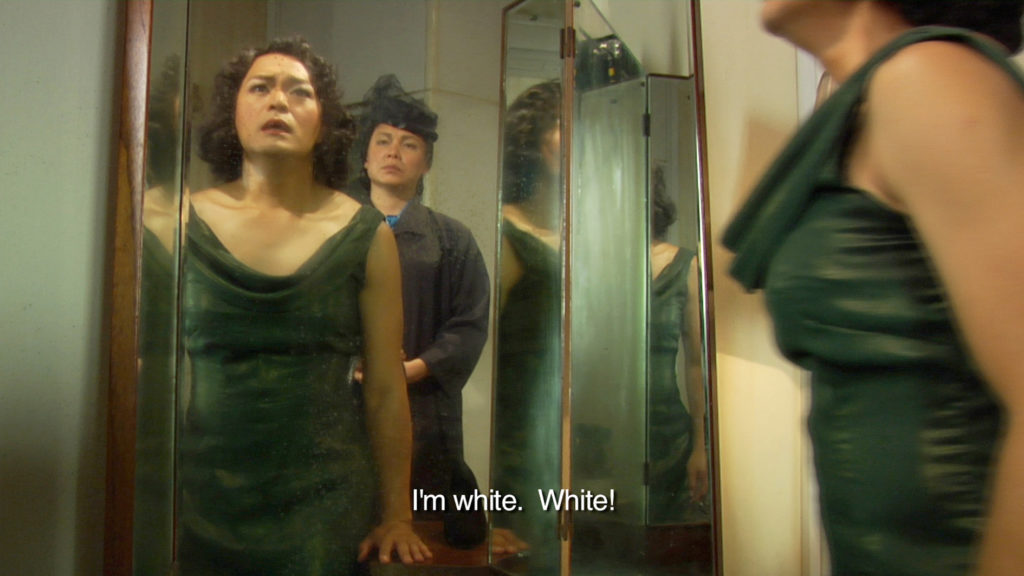

Source: Douglas Sirk, Imitation of Life, 1959

In Life of Imitation, the male actors cross-dress while performing the melodramatic dialogue with their respective foreign language accents, thus producing different levels of distantiation. They open the scene with an understated acting style that inhibits audience identification and contrasts with the hyperbolic performance otherwise characteristic of the melodramatic genre.2 Yet as the scene continues, their acting increases in dramatic expression and they finally embrace with tearful eyes, shown in close-ups that mimic the original frame composition of Sirk’s film. The accompanying music composed for Life of Imitation by Heathcliff Blair, in very close approximation of the original melodic theme, also heightens the emotional impact of the scene.3 Neither the set design nor the blocking in the double-channel video installation operates in parallel. Instead of moving in the same direction on both screens, the characters each move toward the shared center, and the composition, mise-en-scène, and blocking consistently mirror each other, reproducing the prevalence of mirrors in Sirk’s films.4 In Imitation of Life, for example, key scenes tend to feature characters gazing at themselves in mirrors while delivering central lines of dialogue—an effect Wong replicates in his installation. Two side-by-side projections in a loop of under five minutes are set up with “mirrors opposite two video monitors that refract parallel and never-crossing worlds” in the reenactment of Sirk’s key narrative moment (Fang, 4 of 5).

Cuts in each projection coincide with the switching of actors’ roles, making it impossible for viewers to align an individual actor with a particular role, and thereby also destabilizing preconceived notions of race, ethnicity, or gender. In this way, the installation recalls the fantasy of coherent identities Sirk’s Imitation of Life reproduced even while purporting to unravel oppressive racial demarcations. Sirk mobilized the figure of the ‘tragic mulatta,’ a nineteenth-century stock character intended to invoke pity from white readers after the revelation of her ‘true’ identity led to her fall from grace. In classic passing narratives, female characters “are more likely to be punished for passing than are men,” a discrepancy that points to the gendered dimension of the racial passing narrative (Valerie Smith 43).

Wong’s double screen does not project two identical versions of the same scene simultaneously; instead it presents two distinct performances that diverge as a result of the actors’ rotations and spoken dialogue, causing both soundtracks to overlap in some instances of the dialogue and diverge in others when individual lines echo each other. The overall sense of simultaneous recognition of and estrangement from the original film’s famously dramatic scene creates an uncanny effect. By remaking key scenes from art films and usually performing all the character roles himself, Wong, I propose, speaks to the identifications and desires that moving image-cultures evoke among spectators in the contemporary context of global and digital media circulation.

His global work reflects the current technological transformation of art film from celluloid single projection in movie theatres to multiple screens exhibited in spaces such as museums, galleries, and art biennials. Thus, Learning Deutsch with Petra von Kant (2007) is based on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972), and Angst Essen/Eat Fear (2008) restages Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974). The film In Love for the Mood (2009) remakes Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000), while Devo partire. Domani (I must go. Tomorrow, 2011) rewrites an excerpt of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968). Similarly, Life and Death in Venice (2011) reworks Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice (1971), and Persona Performa (2011) restages a section of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), whereas Making Chinatown (2012) reflects on Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974). Residing in Berlin, Germany, Wong has shown his installations in Tokyo, Hong Kong, Toronto, New York, and Florence, among other cities and, in some instances, he tailored an individual exhibit to its specific geopolitical location. Although Wong’s international stature more recently earned him governmental support from his native Singapore, his oeuvre is more closely aligned with the global diaspora of gay film artists. Directors such as Pasolini or Visconti and films such as Death in Venice or Ali: Fear Eats the Soul have inspired his work, as they have that of others.5

I shall argue that Wong confronts viewers with the practices by means of which different media and aesthetics produce and circulate identity at particular historical moments and across the divides of history and geography. Life of Imitation rewrites the American racial binary of black and white depicted in Imitation of Life and transposes it by casting three actors of Indian, Chinese, and Malayan descent in the roles. Sirk’s original female character roles are performed in drag by men, thereby highlighting—consistent with Wong’s other work—the intersections of race and ethnicity with those of gender and sexuality encoded in the various remediations of the original story.6 I demonstrate that Wong’s double-projection moves beyond merely plundering a famous film from the 1950s to forge an artistic production that speaks to us about the medialization of identity in the networks of global art. Moreover, I take seriously the installation’s charge to its viewers to trace the various incarnations of identification, desire, and identity through the different textual manifestations of Imitation of Life, ranging from the 1933 book by Fannie Hurst to the 1934 film by John M. Stahl and the second film version by Sirk.

Wong challenges us to revisit the literary and visual pre-histories that he is reworking and to see them anew through his restaging. His method is best captured by the term that gives this special volume its title: remediation, a concept born out of the possibilities engendered by new media and defined by “digital networking, global reach, interactivity and many-to-many communication” (Flew xv). This ability to excerpt, loop, and offer multiple recombinatory projections of older texts certainly defines Wong’s work. New media’s affinity for convergence, which is primarily understood in relation to the bundling of information, communication, and telecommunication activities, characterizes Wong’s oeuvre insofar as his individual pieces are exhibited not only as distinct installations but also as electronic versions accessible on the web (Lievrouw and Livingstone 393). New media also increase the mobility of images and their producers and thus enable appropriations of visual texts in the art world and in popular and social media. As Wong’s piece shows, and this article suggests, identities were also circulated between different geographic regions prior to the advent of new media and could thus be similarly appropriated. Yet digital and virtual media have increased the speed and quantity of such disseminations to the point where a qualitative shift has occurred.

Changes in media practices heighten our awareness of both the possibilities of a new medium and the characteristics of earlier ones. Wong’s Life of Imitation invites spectators to revisit the process of remediation already inherent in Sirk’s version as a remake of an earlier film adaptation of a book. Wong’s Life of Imitation evokes the specificity of Sirk’s film, but engages meta-textual questions about originality, reproduction, imitation, and the global circulation of visual texts. The next section introduces the different versions of Imitation of Life and analyzes the disavowed presence of ethnic difference in the construction of a racial binary as a common thread across the text’s different instantiations. I conclude this article with a reading of Wong’s piece as an instance of global remediation.

Art Imitating Art

Sirk’s Hollywood blockbuster has remained the most widely known version of the story, even though already remediating the novel by Hurst, and Stahl’s black-and-white film with Claudette Colbert, Freda Washington, and Louise Beavers.7 All three versions tell the intertwined story of two mother/daughter pairs, one white and the other African American, but Sirk’s version deviated significantly from Hurst’s original novel and Stahl’s adaptation. The latter two center on the white woman named Bea Pullman, who builds a financial empire based on abbreviating her first name as B. to efface her gender. She launches a chain of successful restaurants that serve waffles, using the image of African American Delilah Johnston’s radiant face and persona as trademark. In Hurst’s novel, the chain of restaurants is described as attracting hurried and rushed urbanites, who find comfort in the sense of calm and comfort associated with Delilah’s persona, which, in turn, perpetuates the stereotype of the nurturing African American mammy and naturalizes her labor.8 In Hurst’s original version, every store in Bea Pullman’s empire hires an African American woman who duplicates Delilah’s persona, casting her type as reproducible. Stahl’s film transforms the qualities associated with Delilah into a form of visual shorthand, captured by Delilah’s face and smile on the sign Bea displays outside her first restaurant.9

Source: John M. Stahl, Imitation of Life, 1934

Although Bea and Delilah and their respective daughters share a common household, socio-economic distinctions are upheld within the home and in their social activities that reflect their racialized positioning within the wider society. Each mother/daughter pair suffers from a deep conflict the narrative construes as inherently connected to their race and their upward mobility, and that—in the fashion of the maternal melodrama—leaves both mothers lonely without their daughters’ love at the novel’s end. Bea sends her daughter Jessie to boarding school in Switzerland to provide her the knowledge and manners she herself cannot bestow on her because she is too busy with work and also has too limited a social background. But she also wishes to separate Jessie from Delilah’s light-skinned daughter Peola, as the two have become close. Both mothers worry their daughters will not recognize the racialized distinctions that they believe should set them apart. Over the years Bea becomes increasingly estranged from her daughter Jessie. At the peak of her success at the end of the novel, Bea realizes she is in love with her younger assistant Frank Flake who, however, marries her daughter Jessie instead, leaving the humiliated, lonely, yet rich Bea to travel the world, avoiding her only child. Delilah faces a parallel yet different tragedy with her light-skinned daughter Peola. The deeply religious mother wants Peola to embrace her African American identity, including voluntary submission to a status of secondary citizenship. Instead, however, Peola leaves the household in order to move cross-country and pass as a white woman.

Sirk’s later film version excavated a meaning latent to the novel’s original title, namely, its reference to representation as imitation, including the medium of film more specifically. In turn, he changed the original businesswoman Bea Pullman into the photo model Lora Meredith (played by Lana Turner), who becomes an international theatre and film star. With this move, Sirk shifted the commodity association from Delilah to Lora, and correspondingly transferred the focus from marketing the consumption of food to that of the filmic image. This change reflects the different economic contexts of two distinct historical eras. Whereas the years 1933 and 1934 mark a global economic crisis, 1959 belongs to a period of stability and growth. While the early 1930s built upon advances women had made entering the public sphere during the 1920s, the late 1950s concluded a period associated with women’s return to the private sphere following their participation in heavy industries during the Second World War. Conceived in 1933, Bea conquers the public sphere with an underlying desperation to survive, yet exploits Delilah as a commodity fetish. Sirk’s late 1950s imagination envisions Bea’s glamorous counterpart Lora as a visual fetish after a chance encounter at the beach with a male photographer, Steve Archer (John Gavin), and Annie as invisible help in the home.10

Sirk’s Imitation of Life opens with a young mother, Lora Meredith, who has lost sight of her six-year-old daughter Susie (Terry Burnham) on a crowded beach. When she finally finds her, she discovers that Susie has made friends with a light-skinned African American girl, Sarah Jane (Karin Dicker), and her comparatively darker-skinned mother, Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore), whom Lora mistakes for the little girl’s maid. When Lora learns that Annie and Sarah Jane are homeless, she invites them to move in with her and Susie. Within the household’s racialized division of labor and status, Annie immediately falls into the role of the domestic servant. Lora, on the other hand, gradually rises to stardom as a model and actress, accumulating wealth and male admirers, and providing materially for her daughter Susie, but overlooking her daughter’s emotional needs. Susie (Sandra Dee) subsequently falls for Steve Archer, who is in love with her mother, and turns for emotional solace to Annie rather than her own mother.

Yet the real locus of melodrama in Sirk’s version lies with Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner), who appears white and rejects the inferior social position accorded to her. Rebelling against the racial stratification of the Meredith/Johnson household, she rejects her home, including her mother. She attempts a romance with Frankie (Troy Donahue), a white young man in town, who beats her up when he hears from others that she is black. After her mother, Annie, discovers her dancing in a nightclub, Sarah Jane flees the household altogether, leaving behind a note asking her mother not to search for her. During the following years Annie becomes increasingly frail. When a hired private detective finds Sarah Jane working as a revue girl in Los Angeles, Annie flies out to visit her “once more,” which turns into the fateful encounter in Sarah Jane’s motel room taken up as the subject of Wong’s installation. The film ends with the melodramatic staging of Annie’s funeral; Sarah Jane reappears just in time to throw herself on her mother’s casket in despair.

Sirk and the Politics of Melodrama

The efficacy of Sirk’s film in confronting a racist society hinges on the politics of melodrama as a genre eliciting an audience response primarily through tearful identification. Typical for melodrama are “chance happenings, coincidences, missed meetings, sudden conversions, last-minute rescues and revelations, deus ex machina endings” (Neale 6). As Steve Neale explains, melodrama’s implicit assumption that the “spectator often knows more” creates the genre’s simultaneous tears and pleasure (7). He outlines how “particularly moving moments” result from a “structure in which the point of view of one of the characters comes to coincide” with that of the spectator, but often “too late” (7). Linda Williams importantly proposes “a give and take of ‘too late’ and ‘in the nick of time’” (30). The final scene of Imitation of Life—the “most moving and tearful of all scenes in melodrama” according to Neale—illustrates his claim, as Sarah Jane arrives at her mother’s funeral “too late” to reconcile with her (19).

This melodramatic characteristic also organizes the scene in which Annie visits her daughter Sarah Jane out West, shortly before the film closes with Annie’s funeral. Audience members can already infer that Annie will die and that this encounter represents her final good-bye to her daughter, but Sarah Jane is blind to the signs of her mother’s deteriorating health. For the audience, this knowledge intensifies the tragic impact of Sarah Jane’s rejection of her mother. The film indicates that Annie’s increasing exhaustion results from her domestic servitude and the psychical pain estrangement from her daughter causes her, which is highlighted by repeated references to her weakness. Following the scene in which Sarah Jane is beaten up by her boyfriend, Annie finds the address of a bar named Harry’s Club in New York City, where she then watches Sarah Jane performing a song-and-dance number. Through her visible difference but filial association, Annie inadvertently exposes her daughter as African American to the club owner; we learn that Sarah Jane had also taken on a false identity as Judy Brand, a name emphasizing her commodity status. Sarah Jane then abandons Annie in the streets of New York City, where she collapses in tears on some tenement stairs.

Source: Douglas Sirk, Imitation of Life, 1959

The film thus places the guilt for the African American servant’s exhaustion onto her own daughter, a theme taken up in the scene that Wong chose to restage, when Annie asks whether she can sit down and Sarah Jane denies her a seat.11

Yet, even as scholars have repeatedly returned to the motel scene for its pivotal melodramatic impact, it is actually the scene prior that establishes the public form that Sarah Jane’s imitation of white femininity will assume. In that scene, Annie arrives in Los Angeles and goes to watch her daughter perform on stage as a revue girl at the Moulin Rouge, a club catering to a high-class, white clientele. Sarah Jane’s racial difference disappears in a sexualized performance as she merges with the girl chorus of mechanized movements—what Siegfried Kracauer called “the mass ornament”—which relies on and emphasizes the women’s apparent sameness. The slowly turning circular stage on which the women perform displays them seated on individual swivel chairs: they tilt their heads back in mimicry of drinking from oversized champagne glasses while provocatively arching their back and each lifting one leg to connote their wholesale sexual availability. The camera stays at Annie’s eye level, presenting the show from her point of view. But soon a hotel employee appears, presumably asking Annie to leave her position close to the stage. We cannot hear what he says, as the sound of the performance cancels out their dialogue, but we witness the implication that she does not belong to the leisure class privy to this form of entertainment. The moment Annie leaves, the camera shifts to a high-angle shot, rendering Sarah Jane’s sexualized movement on her prop chair subservient to the gaze of the film audience.

Source: Douglas Sirk, Imitation of Life, 1959

In a gesture typical of liberal films about racism, the injuries critiqued by the film’s discourse are reinscribed at a technical and formal level. The camera’s position both sexualizes and morally discredits Sarah Jane while critiquing the limited employment options available to African American women.

The next scene is recaptured by Wong in Life of Imitation. In this penultimate encounter between mother and daughter, Sarah Jane turns away from her mother to address herself in a nearby mirror, insisting, “I am white, white, white.” By contrasting Annie’s desexualized and maternal labor of love for Lora and Susie with Sarah Jane’s performance as a revue girl, the film endorses African American women’s domestic work as morally superior to the sexualized labor the film presents as the only viable alternative. Imitation of Life hereby willfully ignores African American women’s legacy of postwar employment in various positions outside the domestic sphere at a crucial transitional moment in American history.12 The endorsement of the domestic sphere as a site for African American women to engage in ‘natural’ and non-alienated work also depends on depicting Sarah Jane’s labor as an abject imitation of whiteness doomed to fail. While Sarah Jane passes as Linda, a white woman, within the diegesis, the film apparatus sexualizes her as a black woman.

Much of the feminist discussion around Sirk’s film version responds to the fact that Sirk shifted emphasis from the conflict between the white mother/daughter pair to the African American mother/daughter pair and, thus, from romance to race. This shift to a passing narrative also involved resequencing narrative events. In chapter 39 out of 47 in Fannie Hurst’s novel, the light-skinned daughter Peola returns after three years working as a white librarian out West to plead with her mother (in Bea’s presence) to help her making a break from the all-female household in order to live as white and marry a white man. Although the novel implies that this is heart-wrenching for her mother, Peola’s request and decision are presented as one possible and rational response to racism. Following this last appearance, Peola completely disappears from the narrative.

The novel’s “too late” structure applies primarily to Bea and her daughter Jessie. As Bea grows older and her empire is secure enough to allow her to pursue her own desires, she realizes she is in love with her right-hand man, Frank Flake. But at the very moment when she confesses her love to Flake (in the book’s very last short chapter), expecting to announce their engagement to her daughter so all can move in together, Jessie interrupts her to let her know that she and Flake already have plans to get married. Thus, Bea recognizes too late that Flake and her daughter Jessie were romantically involved, a circumstance to which she was blind not only because she had devoted so completely devoted her time to work but, ironically, also because she herself was so in love with Flake. By contrast, Sirk accords the story of the African American mother/daughter pair greater melodramatic weight and shifts the textual emphasis from the romantic competition between the white mother and daughter to the conflict concerning racial embodiment in the United States.

The question whether privileging the racial over the romantic conflict constitutes progressive politics has driven Sirk criticism revolving around Sarah Jane’s racial passing.13 Lauren Berlant frames the film’s racial and gender politics in the context of the role of the female body in the American public sphere, emphasizing especially the theme of branding in the different textual versions. In Sirk’s version, she points out, Sarah Jane blames her mother rather than the state for the racial discrimination she experiences, and chooses passing over her mother’s subordination, while also embracing “a libidinous, assertive physicality” that Berlant sees as “typical of women” (137). Sarah Jane imitates Lora, who presumes that “physical allure is the capital a woman must use to gain a public body” (137). In the diegetic world, Sarah Jane passes in order to demand the same cultural capital accorded Lora. Even if some upward mobility is evident in her move from sleazy Harry’s Club in New York City to the more upscale Moulin Rouge in Los Angeles, as signaled by the increased distance between performer and audience in the two clubs, the film does not accord her the same spectacular attention given over to Lora (and Lana Turner as star of the film), and instead discredits Sarah Jane’s sexuality through its cheap availability as mass reproduction.

Source: Douglas Sirk, Imitation of Life, 1959

Sarah Jane imitates Lora who, according to Judith Butler (who refers to Lora as Lana, proposing that the similarity of their names evokes the star actress Lana Turner), constitutes the film’s feminine icon (5). Her figure signals “the cruelty of whiteness,” owing to its “compulsory normative requirement for desirability” (5). Butler also shows how Lora/Lana, from the very opening shot, appears “ideal, frozen into the photographic pose, available only to the gaze” (13).14 The apparatus creates a “look-don’t touch quality” in Lana’s performance that contrasts with “Sara [sic] Jane’s exaggeration of Lana’s exaggeration” (10).

Source: Douglas Sirk, Imitation of Life, 1959

Source: Douglas Sirk, Imitation of Life, 1959

Sarah Jane’s desire to be touched—in contrast to Lora’s “to-be-looked-at-ness” (Mulvey 1988: 62)—is horrifically transformed into violence when her boyfriend Frankie beats her in a scene that contrasts dramatically with an example of tender touch—Annie massaging Lora’s feet—in the next shot. Physical intimacy is reserved solely for Lora and Annie, but always inscribed within Annie’s subservience, which deflects any possibility of a lesbian reading of the all-female household. Sarah Jane’s tragic desire for human touch finds its most moving expression when she leans her head against the door after Annie leaves her motel room; the closed door as surrogate for her mother’s body presages her embrace of her mother’s coffin in the final scene.

Source: Douglas Sirk, Imitation of Life, 1959

From Ufa to Hollywood: Continuities and Ruptures

By exploring films by Douglas Sirk in light of his immigration from Germany to America in the 1930s (a move he undertook to save his Jewish wife, actress Hilde Jary), not only do continuities and ruptures in his work come into focus, they also lead us beyond considerations of skin color as a dominant signifier of identity and of the United States as the only socio-geographical realm shaping the text’s depiction of identity. For indeed, the scholarly debates over the gender and racial politics articulated by Imitation of Life also apply to his films made in Nazi-era Germany. Sirk had worked very successfully at Ufa, making 13 feature-length films, including The Girl from the Marsh Croft (Das Mädchen vom Moorhof, 1935), Final Accord (Schlussakkord, 1936), The Court Concert (Das Hofkonzert, 1936), Toward New Shores (Zu neuen Ufern, 1937), and La Habanera (1937). The latter two featured Zarah Leander, the Nazi star who came to replace Marlene Dietrich following her departure for Hollywood. Disputes over the political significance of Sirk’s German films variously emphasize aesthetics or gender. Linda Schulte-Sasse produces a potentially subversive reading of Sirk’s Nazi films by focusing on aesthetic and self-reflexive dimensions, whereas Gertrud Koch indicts Sirk for his sadistic camera work in the depiction of femininity, which she regards as a point of continuity between his Nazi era and Hollywood films.

Schulte-Sasse’s overview of the critical scholarship on his films from the Nazi period reveals a radical division between claims that his films accommodated fascist ideology and assertions that his films offered aesthetic subversion (2–6). In a close reading of Final Accord, she argues for aesthetic resistance, claiming Sirk’s work creates a “reflexive space” that can be read “in competing ways, for example, as a ‘Nazi’ film or not” (6). Like scholars who see his melodramas as laden with irony, she places the burden of critical analysis on the audience, a point Koch emphasizes in strong terms. A fascist state creates conditions where double-speak becomes necessary to enable both affirmative and subversive readings. Koch’s damning reading of Sierck/Sirk’s politics first identifies the Sirkian “renaissance” of the early 1970s as a “by-product of the politique des auteurs” launched by directors of the Nouvelle Vague, who “elevated Sirk into the Pantheon of authors” and invented a “new biography” that separated him “from his Nazi features” and “transposed” his nationality into “the country of the admired Dreyer” (14–15). She particularly criticizes Jon Halliday’s view that Ufa offered “enclaves of freedom … after 1933” and that cast Sierck as a “left-wing director” before he left Germany (17). Koch, by contrast, turns to reviews of the Weimar Republic that describe Sirk’s “anti-intellectual, emotionally appealing style of directing,” capturing an evaluation of his work that differs significantly from the scholarly claims that advanced his political rehabilitation in West Germany during the 1980s (17).

Koch identifies a continuity leading from Sirk’s German films to his more famous American melodramas, claiming Sirk’s films channel the excessive emotions they create through an “authoritarian and sadistic gaze” that is directed onto “the body of the sexual woman as a destructive and deformed fetish which needs to be cleansed through a cathartic exorcism” (21). In her reading of his Ufa film, The Girl from the Marsh Croft, she shows how the character of the unwed mother fits into the “racially constituted community” with “the Führer as pater familias” replacing any real fathers (25). In general, she claims, Sirk denounces female sexuality by endowing it with a repulsive quality (29). She concludes her article by turning to Imitation of Life, which she calls “the piéce de resistance of any criticism of Sirk” for his admirers (30). While Koch sees Sirk’s sadistic camera at work in Sarah Jane’s attempt to enter white society, “her return to the black community is staged as a grandiose and tear-jerking march of atonement” (30).

Source: Douglas Sirk, Imitation of Life, 1959

Source: Douglas Sirk, Imitation of Life, 1959

When Sirk shifted the melodramatic focus from the white mother/daughter pair to the African American mother/daughter pair, he sexualized Sarah Jane and portrayed her through a sadistic gaze, particularly in the scenes where she performs sexual availability, and in the scene where Frankie beats her.

Sirk Remaking Sierck Remaking Stahl Remaking Strelitsky Remaking Hurst

Taking our cue from Wong’s installation and following the history of remaking, we find in Sirk’s remake of Stahl’s version a remake of Hurst’s version, and, along the way, directors and writers who are not what they seem to be, but nonetheless successfully pass as unmarked Americans. Layers and complications of national, immigrant, and religious affiliations had to be disavowed in order to create a narrative organized around the racial binary that organizes American public life. Imitation of Life relies on illusions of pure racial categories in order to mobilize one impure character to criticize racism. While the story of passing appears to be gendered female, the textual history of Imitation of Life reveals that Stahl and Sirk are passing as well. A complex network of exchanges, displacements, translations, and projections between ethnicity and race already characterized successful Jewish writer Fannie Hurst’s work. Daniel Itzkovitz points out for example that “readers of her early stories will recognize in Imitation of Life’s mammy Delilah Hurst’s numerous portrayals of all-loving Yiddishe Mamas” (xi). Yet Hurst was also known for her “extraliterary, outspoken commitment to progressive political causes, especially women’s and antiracist issues” (viii).

John M. Stahl, it appears, was born Jacob Morris Strelitsky in the town of Baku (Azerbaijan) and at a young age immigrated with his Russian Jewish family to New York City. As is often the case for those who take on a normative and unmarked identity, Stahl so successfully invented his American biography that the majority of sources note January 21, 1886, in New York City as his date and place of birth; solely the French newspaper Libération published claims that he was not born in the US and that he spent time in prison prior to launching his Hollywood career under the name of Stall (Waintrop). As part of MGM, he was an influential presence in the early Hollywood studio system. A brief article in the San Diego Union in 1950 reports a claim made by his daughter Sarah Appel that his third wife Roxanna Stahl blackmailed him to designate her as his sole heir by threatening to go public about his prison term while a young man in New York and Pennsylvania working under the false names of Jack Stall and John Stoloff.15 John Malcolm Stahl’s World War I Draft Registration Card shows the word “Russia” hand-written in the column that asks: “If not a citizen, of what country are you a citizen or subject?”16 While the name Jacob Morris Strelitsky or the surname Strelitsky do not appear in the 1900 New York City census, the name John Stahl, son of Morris and Margaret Stahl (with a sister Mamie) does, naming Germany as the place of origin.

The most obvious explanation for these inconsistencies would be that the family of immigrating Russian Jews was assigned the name Stahl upon arrival in the U.S., most likely on Ellis Island.17 The anti-Semitism and anti-Bolshevik sentiments alive in Hollywood in the 1930s offer a contextual explanation for why an aspiring director in Hollywood would hide his Russian and Jewish roots. Thomas Doherty documents the anti-Semitism with a leaflet that circulated in Hollywood in 1936, calling on audience members to boycott films with Jewish stars, outing Jewish actors and actresses, as well as those married to Jews, and calling on the public to join “clubs chartered for the purpose of eliminating the enemy—the JEW from all Industry! Become a member of this Legion to make this great country of ours safe from the Jew and Russia” (n.p). The leaflet also illustrates the common tendency to innately link Jews and Russians.

As a biracial character, Sarah Jane embodies the critique of the binary racial system in America. The actress Susan Kohner, however, is not necessarily deemed visibly biracial. She is the daughter of the Mexican actress Lupita Tovar and Austro-Hungarian Jew Paul Kohner, who immigrated from Teplitz-Schoenau to California in 1920.18 He worked for Universal in Europe and left Germany when the Nazis rose to power, becoming one of the most important middlemen who enabled members of the German film industry to immigrate to Hollywood (see Klapdor). The casting of Kohner as Sarah Jane also reveals that Hollywood neither acknowledged its own racism, nor captured the complexity of ethnicity.19

Sirk, in turn, had worked under the Nazis until 1937 and left under dramatic circumstances because his wife was Jewish, changing his name from Detlef Sierck to Douglas Sirk. According to his own account, he was without passport “‘for certain reasons’” and, in order to leave the country, had to first film in Tenerife, then meet his wife in fascist Italy, fake an illness when producers from Germany were looking him up, and travel through Switzerland, France, and Holland, before he was finally hired by Warner Brothers to remake his German success To New Shores (Halliday 55–63). He claims he was courted by Goebbels but made it clear in a letter to him “what [he] thought of the Nazis and everything” and that he would not return to Germany (Halliday 58).

The genealogy of remaking Imitation of Life can thus be seen to encompass not only gendered projections of passing onto a female character, but also displacement of ethnic difference onto African Americans. Wong’s strategy of having actors of different ethnicities embody racialized characters reconstitutes some of the displacements that took place in earlier adaptations. The very presence of the actors delivering the melodramatic dialogue about racial passing captures the simultaneous ethnic embodiment put in the service of discourses about race. It exposes not only the illusion of coherent racial identities that organizes America’s social imaginary, but also the role of film more generally in creating key fantasies predicated upon the visual construction of seamless character identities.20 The web of international migration, exile, and ethnicity is thus more complex than the two films and one novel posit when contrasting light-skinned blackness with undifferentiated and normative whiteness, while also claiming to complicate the race question. The ‘tragic mulatta’ serves to both displace and negate a complex ethnic fabric that has, over time, come to constitute ‘whiteness’ in the United States.

Melodramatic Flamboyance and the Queer Imagination

Wong’s reworking of the story using male actors who cross-dress as Sarah Jane and her mother also brings forth melodrama’s coded gay language. Hurst’s own “flamboyant style” refers not only to her literary work but also to her personal life, which included a scandalously secret marriage with pianist Jacques Danielson, with whom she “shared neither a home nor a name” (Itzkovitz xii). Hurst moved in the sexually liberated and aesthetically vibrant circles of the Harlem Renaissance and was friends with its gay and lesbian artists, including Langston Hughes, Carl Van Vechten, and Dorothy West.21

Flamboyance constitutes a site for transference and exchange of femininity between straight women and gay men. The latter’s exaggerated imitation marks a difference from traditional masculinity, which otherwise denies the expression of any feminine affect. In his essay “The Cinema of Camp (aka Camp and the Gay Sensibility),” Jack Babuscio lists different characteristics of camp, including that of irony and an “aesthetic element,” both associated with Sirk’s films, especially Imitation of Life (120). He also identifies “theatricality” as another aspect, one encompassing “the notion of life-as-theatre,” applicable to “‘passing for straight’” as a fact of gay existence: “The art of passing is an acting art: to pass is to be ‘on stage’, to impersonate heterosexual citizenry, to pretend to be a ‘real’ (i.e. non-gay) man or woman” (123). Since melodrama emphasizes aestheticism and theatricality, it often serves as a foil for camp.

Another lesser-known and much earlier revision of the urtext of Imitation of Life seems to have combined camp with a reversal of the racial identities of the two main female characters. In 1938 Langston Hughes wrote “Limitations of Life,” a short satire of Imitation of Life. The one-act play was performed for “a raucous Harlem audience appreciative of the simple but deadly switch that left a white woman in the role of the obsequious, dialect-speaking domestic servant” hired by a “wealthy black mistress” (Itzkovitz viii). As James V. Hatch and Ted Shines explain in the short preface to their edition of the play, “Hughes wrote four skits to satirize the American motion pictures produced by an industry that perpetuated the concept of white superiority” (223).22 In the one-act play, Mammy Weavers, a rich African American woman, returns home from the opera, and her white maid Audette Aubert, whose name is modeled after that of actress Claudette Colbert in Stahl’s film version, serves pancakes, rubs Mammy Weavers’ feet, and has a daughter “tryin’ so hard to be colored. She just loves Harlem” (225). Audette Aubert speaks in the stereotypical language associated with African American speech in Hurst’s novel and Stahl’s film.

Hughes exposes the text’s reliance on the stereotype of subservient African American women. The use of Imitation of Life as a foil for drag performances apparently continues into the contemporary era with “a stage parody, Imitation of Imitation of Life, featuring drag divas Lypsinka and Flotilla DeBarge” from 2000 (Itzkovitz ix). Drag and camp tend to exaggerate already excessive performances of gender found in original templates on which drag performers base their shows; but as indicated by the example of Hughes, who was one of the openly gay members of the Harlem Renaissance, gender was always already racialized, and African American consumers and producers of culture were highly aware of this.

Remediation: New Media Remakes Old Media

If my analysis thus far demonstrates that one can retrace a genealogy of literary and filmic adaptations and parodies for this text, what is the particularity of Wong’s contemporary remediation process? In order to address this question, I will offer a brief account of ‘remediation’ as a concept that emerged in the context of new media. According to David J. Bolter and Richard Grusin, media generally endeavor to erase any traces of their own processes in order to achieve an overall sense of immediacy (5). While advocates of virtual reality tout its close approximation of the experience of social life, Bolter and Grusin show that the notion of immediacy has a longer history. They outline the development of perspective in painting, which “promised immediacy through transparency,” and add that the close connection between Albertian perspective and Descartes’ spatial mathematics results in a “peculiar way of seeing that dominated Western culture from the single vantage point“ (24). According to Bolter and Grusin, a “linear perspective could be regarded as the technique that effaced itself as technique,” and functioned as a forerunner of contemporary media strategies for obscuring its own presence (24).

New media’s newness also appears in the ways old media is refashioned (15). Artists achieve success based on the degree to which they are able to erase the traces of mediation. When a media form is new, it heightens spectatorial and consumer awareness of its presence: “Although each medium promises to reform its predecessors by offering a more immediate or authentic experience, the promise of reform inevitably leads us to become aware of the new medium as a medium” (Bolter and Grusin 19). Mulvey explains that even though “the arrival of digital technology created an opposition between the old and the new, the convergence of the two media translated their literal chronological relation into a more complex dialectic“ (2006: 26). In that context, she emphasizes the ability of digital media to detach film material from its original site.

Recent art pieces address the shift from celluloid film to digital media by remediating films from the past. They often invite audiences to reflect on the ways in which old media technologies, such as film, have shaped our sense of history and also our memories. As Mulvey points out “video and digital media have opened up new ways of seeing old movies.” She explains that “a return to the past through cinema is paradoxically facilitated by the kind of spectatorship that has developed with the use of new technologies, with the possibility of returning to and repeating a specific film fragment” (2006: 8). These artistic practices contrast with Bolter and Grusin’s argument that new media aim for the illusion of capturing reality without medialization.

Life of Imitation belongs to a group of contemporary installations that rework films in digital multiple projections and pay homage to original films and enable a new, sometimes critical, viewing experience. For example, Amie Siegel’s two-channel video installation Berlin Remake (2005) consists of a double projection of sequences of original DEFA films and her reshooting of the exact same scenes in the same location; the effect is uncanny, foregrounding the temporal difference between the GDR and the post-Wall period (see Mennel). Similarly, Péter Forgácz’s The Kaiser Going for a Walk (Der Kaiser auf dem Spaziergang, 2003) digitizes an early silent film of the exiled emperor going for a walk sometime in the early 1920s. The term remediation captures the different dimensions involved in the remaking process: the shift from celluloid to digital, the subtle revision of the content, and the accompanying change in screening environment, from the movie theater to either the gallery or museum. Siegel and Wong create a disjuncture between the original and the remake by reshooting scenes. At the same time, the striking similarity of the remake creates an uncanny effect. In a paradoxical process, it is precisely the similarity that heightens the awareness of the difference.

Neither Wong, Siegel, nor Forgács is German, yet all have produced installations that rework German films and that have been exhibited in Germany and abroad. Digital remediation enables increased mobility for artists and their art works, as the digital allows for easy excerpting, mixing, duplicating, storing, reproducing, sending, and receiving. Nevertheless, the works mentioned here do reference national frameworks in Germany, Singapore, the US, and Hungary. Life of Imitation captures the sense of both artistic mobility and grounding in location in a piece created by a Singaporean living in Germany, reworking an American film directed by a German in exile, in an installation shown first in the Singaporean Pavilion in Italy.

Global Remediation of Life of Imitation

Wong’s installation reflects Bolter and Crusin’s description of new media’s characteristics, but it does not erase the traces of (re)mediation. Instead it foregrounds its own and the past history of the mediation of this particular text, including the global circulation of mediations of race, ethnicity, and gender. The installation updates the original mise-en-scène with a television set from the 1970s and by proliferating the Hollywood monoscreen to reflect the multiplicity of screens in contemporary visual culture. The television set, however, is not without significance. It connects Life of Imitation to Fassbinder’s earlier reworking of Sirk’s All that Heaven Allows (1955), a love story about a suburban widow named Cary Scott (Jane Wyman) who falls in love with her gardener Ron Kirby (Rock Hudson) and is consequently ostracized by members of her upper-class small-town community and chided by her children. It inspired Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), the love story between an elderly cleaning woman, Emmi (Brigitte Mira), and a younger Moroccan immigrant worker, Ali (El Hedi ben Salem), in West Germany.23 In All that Heaven Allows, Cary’s adult children give her a television for Christmas after she breaks off her relationship with Ron. The television becomes associated with an alienated medialized culture, hereby both metonymizing Cary’s loneliness in her home and contrasting with the authenticity associated with Ron, a character molded in the non-technological tradition of Henry David Thoreau. Recent scholarship has further linked actor Rock Hudson’s homosexuality to a complex and disavowed subtext in the Sirkian oeuvre.

Source: Douglas Sirk, All That Heaven Allows, 1955

The key scene involving the television returns in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul: Emmi invites her adult children into her living room to announce that she has fallen in love with Ali. When she formally introduces him, a tracking shot registers her children’s silent disapproval, and then her son Bruno gets up, angrily kicks her television, and all the children leave. The scene seems to express a more aggressive attitude towards television as a medium that, in that era, had begun competing with film for audiences.

Source: Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (Angst essen Seele auf), 1974

Fassbinder himself drew attention to this scene by arguing that Ali: Fear Eats the Soul is “set in a coarser, more brutal world,” but that “the process of giving a television set instead of a man appears much more brutal” (Burkel 42). Both films point to media’s historicity via television. In Sirk’s film there is a literal dimension to this when Cary glimpses her own lonely image reflected on the television screen as it is being delivered into her home.

If screens as such have more recently come to preoccupy art historians and film scholars alike (see Mondloch, Friedberg), Wong’s installation also emphasizes the continuous significance of the body. By substituting the two famous actresses—Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner—with three male actors of Chinese, Malayan, and Indian background, he refracts the American racial binary of black and white that organizes Sirk’s film and points towards Hollywood’s unacknowledged body politic. This casting strategy creates multiple levels of estrangement, which, in turn, reflect on the original text’s staging of Sarah Jane’s feelings of non-belonging. Ethnically coded actors perform what Katrin Sieg (2002) has termed “ethnic drag,” providing a complex layering of ethnic and racial identities that organize social meaning. Wong inserts global subjects into the bifurcated racialized American discourse and highlights the transnational quality of such canonical and widely circulating texts.

The three actors switch roles at every cut; we do not witness the switch, only its effect. The roles remain consistent, but switching the actors undermines spectators’ confidence in their own capacities for recognition. The technique presents a cognitive challenge to reading the ethnic, gender, and racial appearance of the characters without subverting the rules of continuity editing with which classical cinema facilitates the imaginary coherence of time and space. Our disorientation is compounded in Wong’s installation because female roles are played by male actors in costumes modeled after Sirk’s 1959 version. The shuffling of male actors also repeatedly undermines our understanding of mother-daughter roles, otherwise foundational to the structure of the maternal melodrama, as all three actors play mother and daughter at different points in the installation. The title Life of Imitation mirrors its historical predecessor Imitation of Life, repeating the words of the original title in reverse order. The two screens of the double projection reflect each other, creating a mise-en-abyme. But because the actors change places at each cut, at each point in the installation the same character is performed by a different actor in the concurrent mirror versions, thereby also unraveling the understanding of representation as mirroring reality on a meta-textual, abstract level.

Cuts organize shot-reverse-shots, which Kaja Silverman, following Stephen Heath, sees as a key device for suturing audiences into a film: “films are articulated and the viewing subject spoken by means of interlocking shots” as the “shot/reverse shot” “reduplicate[s] the history of the subject” (220). Traditionally, these shots appear in temporal sequence, but Wong also places them side-by-side. Silverman argues that the pleasure of cinema relies on the spectator’s willingness to permit “a fictional character to ‘stand in’” for the viewing subject (222). Thus, suture occurs when the “viewing subject says, ‘Yes, that’s me’, or ‘that’s what I see’” (222). Wong’s strategy of reproducing the cuts of the original film, but switching the actors at those exact moments, asks spectators to attend to the bodies within the space of the film and, following Heath and Silverman, deconstructs the notion of the coherent subject that Imitation of Life sets forth. Sarah Jane’s role opens up the possibility of a disjuncture between appearance and self-identification and thus also invites identification and projection for those who desire to explore the performance of gender detached from the assignment of biological sex. Wong draws attention to the fact that desire and identification in the cinema are guided by formal choices, such as cuts, and the bodies present on the screen.

Life of Imitation not only reproduces Singaporean multiculturalism24 in an originally American text; its cross-dressing also makes it a subversive text in a Singaporean society that otherwise represses homosexuality.25 Kenneth Paul Tan explains that in Singapore the “discourse on the patriarchal, monogamous, and heterosexual family imposes a restriction on the erotic possibilities of Singaporeans, legitimizing heterosexual unions, … while delegitimizing (condemning and repressing) other polymorphous erotic expressions such as homosexuality” (33). Life of Imitation thus takes on different significance in distinct sites of its reception, while also accruing meaning in its global circulation. The installation comments on passing as a multivalent process that can result from and reproduce racist, sexist, and homophobic structures and forces, but that can also foreground and critique these.26

By doubling the performance and circulating the actors, Life of Imitation achieves a paradoxical effect: it is able to disaggregate sound from image, even though bodies produce their actual voices.27 The out-of-sync double projection of Life of Imitation provides critical reflection even while reenacting and reproducing the narrative structure of the original by employing the formal and technological possibilities of new media. Life of Imitation deconstructs the textual representation of passing from the inside out instead of offering an alternative narrative. It remediates Imitation of Life and in that process appropriates the melodramatic gender politics to exercise a subtle gay critique. The physicality of the actors emphasizes the interplay between the technological possibilities of new media and the continuing importance of actual embodiment in producing the affective dimensions of melodrama, most especially through the human and accented voice.

In general, the installation of film art in the expansive space of the gallery and museum aims to address the spectator on a meta-level of reflection, often by way of a multi-screen format. The experience of shifting actors and out-of-sync yet doubled sound performed with different accents undercuts immersion in the melodrama and instead invites viewers to reflect on the performance and its revision of earlier instantiations of the text. In the gap that emerges between the moment of recognition and recollection of a familiar text, on the one hand, and the difficulty of recognizing characters based on the incongruence of actor and role, on the other, viewers are asked to reflect on the text’s genealogy with particular attention to embodied performance and the larger questions this particular staging evokes about the mediation of gender, race, and ethnicity across time and space.

When Wongtransforms popular melodrama into installation art, discourses of gender are activated not only on the level of content but also in the gendering of high art and low culture. Questions of femininity have traditionally defined the domestic and maternal melodrama as the genre to which Imitation of Life belongs. Melodrama associated with the so-called women’s film of classical Hollywood reached its zenith when film was still associated with the darkened theatre, a site of anonymity that enables identification, voyeurism, and tearful catharsis. Multi-screen installation art, by contrast, appears in settings that work against immersion and identification: in the open and well-lit spaces of museums and galleries, where audience members are aware of each other in relationship to the space and its screen(s).

Melodrama as a mode of exaggerated expression circulates not only in western cinemas, but is also indigenous to cinemas of South-East Asia and the Middle East. Its codes often extend beyond individual films to shape their extra-textual context, for example, in the public persona of a star or, in the case Life of Imitation, in the form of hand-painted posters. Hu Fang relates how Wong “rediscovered hand-painted movie billboards, as well as their gradual disappearance in Singapore. He tracked down the last remaining billboard painter in Singapore, Neo Chon Teck, and commissioned him to make posters for the pavilion” (4 of 5). According to Fang, the gradual disappearance of painted movie billboards correlates with the vanishing film culture of “Singapore’s golden age in the 1950s and 60s” (4 of 5). Symptomatic of that loss is the transformation of film houses into shopping centers and karaoke parlors, with Wong’s memories of his “own cinematic heritage from Singapore” serving as inspiration for his work (Uttam 2 of 4). This concern with memory may be understood as a response to radical modernization processes, particularly in Singapore.

The hand-painted posters also added a vernacular layer to Wong’s complex spatial and technical installation at the Venice Biennale, and shed further intriguing light onto how Wong remediates both old and new media and bridges past, present, and future. Neo Chon Teck’s artisanal creation of billboards displaying the very strokes of his paintbrush, also contrasts with the multi-layered authorship of Imitation of Life.28 When accompanying Wong’s exhibition in the Singapore Art Museum and the Hara Museum for Contemporary Art in Tokyo in 2011, these posters exemplify how contemporary remediation of 1950s Hollywood melodrama not only expands spatially inside the Singapore pavilion at the Venice Biennale, but also globally, from Berlin to Singapore and Tokyo, and indeed, undergoes deterritorialization via circulation on the Internet.

Conclusion

Life of Imitation captures the mediated history of Imitation of Life, whose global circulation offered melodramatic scripts of gendered racial belonging and familial relations. Remediation offers homage to the original text, but need not exclude critique; ideally it teases out the productive possibilities in the original text instead of faulting it for not living up to its critical potential. Building on the ways melodramatic hyperbole has long served as a foil for gay male resignification, the cross-dressing actors of Life of Imitation mimic performances of unstable identity categories. Life of Imitation works against melodramatic manipulation through cross-gender casting, the actors’ circulation among the roles, the decontextualization of the melodramatic sequence at hand, and the doubling of the screens. The piece appropriates the terms of Hollywood melodrama for a remediation of race, gender, and ethnicity in the context of the global flow of images. The three dominant ethnicities of Singapore and the Italian and English subtitles for the Venice Biennale mark the installation as multi-lingual and mobile. By inserting subaltern and queered bodies into an iconic scene from Imitation of Life, Wong asks spectators to reflect on the global circulation of melodramatic key texts and the accompanying representational politics that produce perceptions of gender and race. Life of Imitation simultaneously validates the original film’s productive potential and ruptures the conservative discourse of race generally inscribed into maternal melodrama.

Works Cited

Babuscio, Jack. “The Cinema of Camps (aka Camp and the Gay Sensibility).” Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject: A Reader. Ed. Fabio Cleto. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1999: 117–35.

Berlant, Lauren. “National Brands, National Body: Imitation of Life.” The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008: 107–67.

Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1999.

Burkel, Ernst. “‘Reacting to What You Experience: Ernst Burkel Talks with Douglas Sirk and Rainer Werner Fassbinder.” The Anarchy of the Imagination. Interviews, Essays, Notes: Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Eds. Michael Töteberg and Leo A. Lensing. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992: 41–44.

Butler, Jeremy G. “Imitation of Life (1934 and 1959): Style and the Domestic Melodrama.” Imitation of Life: Douglas Sirk, Director. Ed. Lucy Fischer. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991: 289–301.

Butler, Judith. “Lana’s ‘Imitation’: Melodramatic Repetition and the Gender Performative.” Genders 9 (Fall 1990): 1–18.

Comolli, Jean-Louis. “L’aveugle et le miroir ou l’impossible cinéma de Douglas Sirk.” [“The Blind Man and the Mirror or the Impossible Cinema of Douglas Sirk.”] Cahiers du Cinéma 189 (April 1967): 14–19.

“Daughter of Film Man Tells ‘Threat.’” San Diego Union (August 28, 1950): 4.

Doherty, Thomas. Hollywood and Hitler, 1933–1939. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Fang, Hu. “Ming Wong: Essay II. Stranger on the Road.” ART IT:

http://www.art-it.asia/u/admin_ed_feature_e/GPfvNUIKFEW298ugHqB1/. Accessed December 14, 2013.

Fenner, Angelica. Race under Reconstruction in German Cinema: Robert Stemmle’s Toxi. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011.

Fischer, Lucy, ed. Imitation of Life: Douglas Sirk, Director. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991.

Fischer, Lucy. “Three-Way Mirror: Imitation of Life.” Imitation of Life: Douglas Sirk, Director. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991: 3–28.

Flew, Terry. New Media: An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Friedberg, Anne. The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2006.

Halliday, Jon. Sirk on Sirk: Conversations with Jon Halliday. London: Faber and Faber, 1997.

Harvey, James. “Sirkumstantial Evidence.” Film Comment 14.4 (July/August 1978): 52–59.

Heung, Marina. “‘What’s the Matter with Sarah Jane?’: Daughters and Mothers in Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life.” Imitation of Life: Douglas Sirk, Director. Ed. Lucy Fischer. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991: 302–24.

Hill, Michael, and Lian Kwen Fee, eds. The Politics of Nation Building and Citizenship in Singapore. London: Routledge, 1995.

Hughes, Langston. “Limitations of Life.” (1938) Black Theatre USA: Plays by African Americans, The Recent Period 1935–Today. Eds. James V. Hatch and Ted Shine. New York: The Free Press, 1974, 1996: 223–25.

Hurst, Fannie. Imitation of Life. (1933) Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Hurst, Fannie. “Zora Hurston: A Personality Sketch.” (1961) Imitation of Life: Douglas Sirk, Director. Ed. Lucy Fischer. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991: 173–76.

Hurston, Zora Neale. “Two Women in Particular.” Dust Tracks on a Road: An Autobiography. New York: Harper Collins, 1991: 173–76.

Itzkovitz, Daniel. “Introduction.” Imitation of Life (by Fannie Hurst). Ed. Daniel Itzkovitz. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004: vii–xlv.

Klapdor, Heike. Ich bin ein unheilbarer Europäer: Briefe aus dem Exil.Berlin: Aufbau, 2007.

Koch, Gertrud. “From Detlef Sierck to Douglas Sirk.” Film Criticism 23.2–3 (Winter/Spring 1999): 14–32.

Kohner, Pancho. Lupita Tovar: The Sweetheart of Mexico: A Memoir. N.P.: Xlibris Corporation, 2011.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “The Mass Ornament.” The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays. Ed. Thomas Y. Levin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995: 75–86.

Lievrouw, Leah A. and Sonia Livingstone, eds. The Handbook of New Media. London: Sage, 2002.

Manring, M. M. Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998.

Mennel, Barbara. “The Architecture of Heimat in the Mise-en-Scène of Memory: Amie Siegel’s Video Installation.” Heimat at the Intersection of Memory and Space. Eds. Friederike Eigler and Jens Kugele. Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2012: 108–22.

Mondloch, Kate. Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Feminism and Film Theory. Ed. Constance Penley. London: Routledge, 1988: 57–68.

Mulvey, Laura. Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image. London: Reaktion Books, 2006.

Neale, Steve. “Melodrama and Tears.” Screen 27 (1986): 6–22.

Nichols, Bill. Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Schulte-Sasse, Linda. “Douglas Sirk’s Schlußakkord and the Question of Aesthetic Resistance.” The Germanic Review 73.1 (Winter 1998): 2–28.

Sieg, Katrin. “Remediating Fassbinder in Video Installations by Ming Wong and Branwen Okpako.” Transit: A Journal of Travel, Migration and Multiculturalism in the German-Speaking World 9.2 (Summer 2014): http://transit.berkeley.edu/2014/sieg/.

Sieg, Katrin. Ethnic Drag: Performing Race, Nation, Sexuality in West Germany. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002.

Silverman, Kaja. “Suture.” (excerpts) (1983) Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology: A Film Theory Reader. Ed. Philip Rosen. New York: Columbia University Press, 1986: 219–35.

Smith, Jeff. “Black Faces, White Voices: The Politics of Dubbing in Carmen Jones.” The Velvet Light Trap 51 (Spring 2003): 29–42.

Smith, Valerie. “Reading the Intersection of Race and Gender in Narratives of Passing.” diacritics 24.2–3 (Summer-Fall 1994): 43–57.

Tan, Adele. “Ming Wong: Essay I. The Scene is Elsewhere: Tracking Ming Wong.” ART IT:http://www.art-it.asia/u/admin_ed_feature_e/zoJ9KmD2WbsCuPreEwj1/. Accessed December 14, 2013.

Tan, Kenneth Paul. Cinema and Television in Singapore: Resistance in One Dimension. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishing, 2008.

Uttam, Payal. “Ming Wong, the chameleon artist, on Hong Kong cinema and Turkish porn.” CNN Travel (May 24, 2011):http://travel.cnn.com/hong-kong/play/does-art-have-be-beautiful-025471. Accessed December 15, 2013.

Waintrop, Edouard. “Actualité de la cinephilie. Le mélodrame strict de John M. Stahl. Saint-Sébastien rend hommage à un maître oublié.” Libération (September 24, 1999): http://www.liberation.fr/culture/1999/09/24/actualite-de-la-cinephilie-le-melodrame-strict-de-john-m-stahlsaint-sebastien-rend-hommage-a-un-mait_284379. Accessed December 5, 2013.

Williams, Linda. Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Films and Installations Cited

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (Angst essen Seele auf). Dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Perf. Brigitte Mira, El Hedi ben Salem, Barbara Valentin, Irm Hermann. 1974.

All that Heaven Allows. Dir. Douglas Sirk. Perf. Jane Wyman, Rock Hudson. 1955.

Angst Essen/Eat Fear. Ming Wong. 2008.

Berlin Remake. Amie Siegel. 2005.

Carmen Jones. Dir. Otto Preminger. Per. Dorothy Dandridge, Joe Adams, Harry Belafonte. 1954.

Chinatown. Roman Polanski. Perf. Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway, John Huston. 1974.

Death in Venice. Dir. Luchino Visconti. Perf. Dirk Bogarde, Romolo Valli, Mark Burns. 1971.

Far from Heaven. Dir. Todd Haynes.Perf. Julianne Moore, Dennis Quaid, Dennis Haysbert. 2002.

Final Accord (Schlussakkord). Dir. Detlef Sierck. Perf. Willy Birgel, Lil Dagover, Mária Tasnádi Fekete. 1936.

I must go. Tomorrow (Devo partire. Domani). Ming Wong. 2011.

Illusions. Dir. Julie Dash. Perf. Lonette McKee, Rosanne Katon, Ned Bellamy. 1982.

Imitation of Life. Dir. Douglas Sirk. Perf. Lana Turner, John Gavin, Sandra Dee, Susan Kohner, Juanita Moore. 1959.

Imitation of Life. Dir. John M. Stahl. Perf. Claudette Colbert, Louise Beaver, Fredi Washington, Warren William, Rochelle Hudson. 1934.

In Love for the Mood. Ming Wong. 2009.

In the Mood for Love. Dir. Wong Kar-wai. Perf. Tony Leung Chiu Wai, Maggie Cheung, Ping Lam Sui. 2000.

La Habanera. Dir. Detlef Sierck. Perf. Zarah Leander, Ferdinand Marian, Karl Martell. 1937.

Learning Deutsch with Petra von Kant. Ming Wong. 2007.

Life and Death in Venice. Ming Wong. 2011.

Life of Imitation. Ming Wong. 2009.

Making Chinatown. Ming Wong. 2012.

Persona. Dir. Ingmar Bergman. Perf. Bibi Anderson, Liv Ullmann, Margaretha Krook. 1966.

Persona Performa. Ming Wong. 2011.

Teorema. Dir. Pier Paolo Pasolini. Perf. Silvana Mangano, Terence Stamp, Massimo Girotti. 1968.

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant. Dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Perf. Margit Cartensen, Hanna Schygulla, Katrin Schaake. 1972.

The Court Concert (Das Hofkonzert). Dir. Detlef Sierck. Perf. Martha Eggerth, Johannes Heesters, Kurt Meisel. 1936.

The Girl from the Marsh Croft (Das Mädchen von Moorhof). Dir. Detlef Sierck. Perf. Hansi Knoteck, Ellen Frank, Friedrich Kayßler. 1935.

The Kaiser Going for a Walk (Der Kaiser auf dem Spaziergang). Dir. Péter Forgácz. 2003.

To New Shores (Zu neuen Ufern). Dir. Detlef Sierck. Perf. Zarah Leander, Willy Birgel, Edwin Jürgensen. 1937.

Additional Websites

http://www.mingwong.org/index.php?/project/life-of-imitation/

http://www.themediamusiccompany.com/heathcliff_blair_biography.html

http://www.themediamusiccompany.com/life_of_imitation_heathcliff_blair.mp3

http://interactive.ancestry.com

- This and all other information regarding the individual pieces and exhibitions comes from Ming Wong’s rich website: http://www.mingwong.org/index.php?/project/life-of-imitation/ (Accessed December 16, 2013). ↩︎

- I am retaining the term genre instead of approaching melodrama as “a broad aesthetic mode,” as does Linda Williams (12). Her use of the notion of “mode” allows Williams to situate cinematic “melodramas of black and white,” in a much longer and diverse medial history. Her magisterial account of melodramatic configurations “leaping” from literature, to performance, to musical, to film, and to television is convincing and impressive. However, retaining the term “genre” keeps the focus on distinctions between different media. Discussions of genre in film studies identify correlations among audience expectations, style, narrative, reception, and marketing along gendered lines; for example, the contrast between the masculine-coded Western films and the feminine-coded romance movies. The association between melodrama and femininity shapes my own argument. Scholarship on the melodrama genre has also led to systematic categorizations of subgenres, such as the maternal, domestic, and family melodrama. Also, Wong’s installation explicitly reworks a genre film from the late 1950s. ↩︎

- For Heathcliff Blair’s background, see: http://www.themediamusiccompany.com/heathcliff_blair _biography.html. For the score of Life of Imitation, go to: http://www.themediamusiccompany .com/life_of_imitation_heathcliff_blair.mp3 (accessed December 16, 2013). ↩︎

- Sirk himself stated: “The mirror is the imitation of life. What is interesting about a mirror is that it does not show yourself as you are, it shows you your own opposite” (Fischer 3). Sirk’s predilection for mirrors is widely acknowledged in scholarship on his work. Jeremy G. Butler calls the mirror “Sirk’s trademark” (299). The “Sirkian system” emphasizes surfaces, such as windows and mirrors, but also frames, such as window and door frames, as well as a mobile camera that shoots characters via mirroring surfaces or entraps them by such framing. One of the early key essays in analyzing the Sirk touch was Jean-Louis Comolli’s “L’aveugle et le miroir ou l’impossible cinéma de Douglas Sirk” (The Blind Man and the Mirror or the Impossible Cinema of Douglas Sirk) in a special dossier on Douglas Sirk in Cahiers du Cinéma in 1967. ↩︎

- For a discussion of Wong’s Lerne Deutsch mit Petra von Kant, which anticipates the concerns of Life of Imitation, see Katrin Sieg’s contribution to this special volume. ↩︎

- Both art reviewers and Wong himself in interviews have been sensitive to and perceptive about audience reactions to his films, and Wong emphasizes his personal relationship to the films that he uses as a foil for his own work. Hu Fang in “Ming Wong: Essay II, Stranger on the Road,” puts it this way: “Every time images from the movies are reincarnated in our own lives—every time there is a coincidence between the movies and ourselves—a new life comes into being. Through Ming Wong’s process of reenactment, these images, which both preserve and exceed consumption, take on a new life” (1 of 5). Fang continues specifically about Life of Imitation, “While these performances appear to imitate imagery from preexisting films, they are also a catalyst for the exercise of memory. They are a fresh rehearsal of images that formerly existed in the minds of the audience” (2 of 5). Adele Tan also considers the audience of Life of Imitation: “In Life of Imitation the black mother and her daughter who passes as white in Douglas Sirk’s film Imitation of Life are reinterpreted by three male actors of different ethnicities who cross-dress for the two female parts and who seamlessly swap roles through the video. Two facing projections of this remake are then doubled by their reflections in mirrors placed beside the projections. But for whom does Wong intend these dispersals, reversals and misrecognitions? These diegetic breakdowns have been summarily accounted for as being motivated by Wong’s outsider status, his racial otherness in Berlin and the dispossession of his cultural memory in Singapore” (4 of 6). ↩︎

- Film Studies scholarship continues to privilege Sirk’s film. See Berlant, Judith Butler, Fischer, and Heung. Sirk’s place in film studies was initially marred by an intellectual disdain for ‘the weepy’, but then embraced by a generation of scholars and filmmakers on the basis of a renewed interest in melodrama. A similar reception has defined the work of Fannie Hurst, as Daniel Itzkovitz observes in the 2004 edition of her original novel from 1933: “Fannie Hurst remains largely forgotten. When she has been noticed in recent years, it is usually either as a footnote to discussions of Zora Neale Hurston, the great folklorist and novelist of the Harlem Renaissance with whom she had an intimate friendship” (xv). While Hurst’s work has experienced a resurgence of attention, thanks to his efforts, he also points out that even though Hurst was among the bestselling writers around 1918, her literary status suffered during the rise of modernism, especially because of her association with a feminine-coded melodramatic style. In this regard, her reception history parallels that of Sirk in film studies. ↩︎

- Williams states: “The figure of continuity with the racially integrated, rigidly hierarchical, agrarian past and the racially segregated urban future was the mammy” (202). ↩︎