Reimagining the German-Polish Borderlands in Nowa Amerika and Słubfurt

TRANSIT vol. 14, no. 1

Karolina May-Chu

Reimagining the German-Polish Borderlands in Nowa Amerika and Słubfurt[1]

Abstract

Nowa Amerika and Słubfurt are two related activist art projects that are set in the German-Polish borderland. Nowa Amerika is an imagined country, and Słubfurt its capital. This contribution introduces these projects and examines their underlying cosmopolitan principles and their strategies of reality construction and performance. The analysis highlights how Nowa Amerika intervenes in the borderland’s spatial and temporal reality and creates new narratives that challenge established political, cultural, and social boundaries. On the one hand, the projects engage critically with existing borders and produce a cosmopolitan vision for the borderland by playfully subverting the borders of the nation state: They remap the borderland as a shared space, for example, through the creation of new cartographies or by bringing people together to form cross-border networks within the local community. On the other hand, their decided focus on the present and future means that historical context is at times oversimplified or elided, thus blurring the cosmopolitan vision. This article invites thinking about the tensions and difficulties that are embedded in cosmopolitan projects, as well as the challenges and taboos in the relationship between Germany and Poland.

Keywords: Germany, Poland, borderland, cosmopolitanism, Nowa Amerika, Słubfurt, Frankfurt (Oder), Słubice, performance, activist art

Introduction

In the heart of Europe, stretching along the German-Polish border, lies the country of Nowa Amerika with its capital Słubfurt. It is likely unfamiliar to most travelers, and conventional maps provide no assistance in finding it. Nonetheless, it is a real place with clear signposts in the German-Polish present: Nowa Amerika has a constitution and a government, an anthem, a flag, and its own currency. It even boasts a university, a radio station, and a newspaper.[2] Its territory is laid out in several maps, and a guidebook explores its sites and landmarks. But what is this place that both exists and does not exist at the same time? In short, Słubfurt and Nowa Amerika are activist art projects that work through community engagement and aim to create positive identification opportunities for people in the region.[3] Everything began in 1999 when artist-activist Michael Kurzwelly founded the fictitious town Słubfurt by conceptually merging the border towns Frankfurt an der Oder and Słubice. Then, in 2010, Kurzwelly and his colleague Andrzej Łazowski, together with other German and Polish artist-activists, expanded the project and created an entire “country,” which they named Nowa Amerika. An event announcement from 2022 states that more than 300 activists (among them artists, journalists, students, retirees, and asylum seekers) are involved in the project (Brandenburgische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung). Financing for Nowa Amerika comes from various sources (mainly European and German), and over the years, it has been recognized with numerous awards, including the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesverdienstkreuz am Bande) for Kurzwelly in 2019.

The name for this imagined country was inspired by the little-known history of a settlement named “Neu Amerika,” which was established in the reclaimed marshlands of the Oder River, or “Oderbruch,” in the eighteenth century. The American frontier and pioneer spirit served as further, and more readily recognizable, inspirations for the project. While this reference was originally articulated in positive terms, the 2020 book The Message of Nowa Amerika (hereafter The Message) complicates this view and posits that America’s status as a “paradise of never-ending possibilities” was “achieved by exploiting the slaves and crimes agains [sic] the indigenous people.” Nowa Amerika, the statement continues, proposes a different model, one that is even “diametrically opposite to the [intention], desires and aims of the powerful brother” (Kurzwelly and Stefański 9).[4] Kurzwelly, who continues to be the main spokesperson and most recognizable face of the project, envisions Nowa Amerika as a shared space that brings people from both sides of the border closer together to help overcome the divisiveness in German-Polish relations. At the same time, the organizers also try to expand their original focus on Germany and Poland and espouse a global consciousness by including newly arrived immigrants or organizing events with international guests.

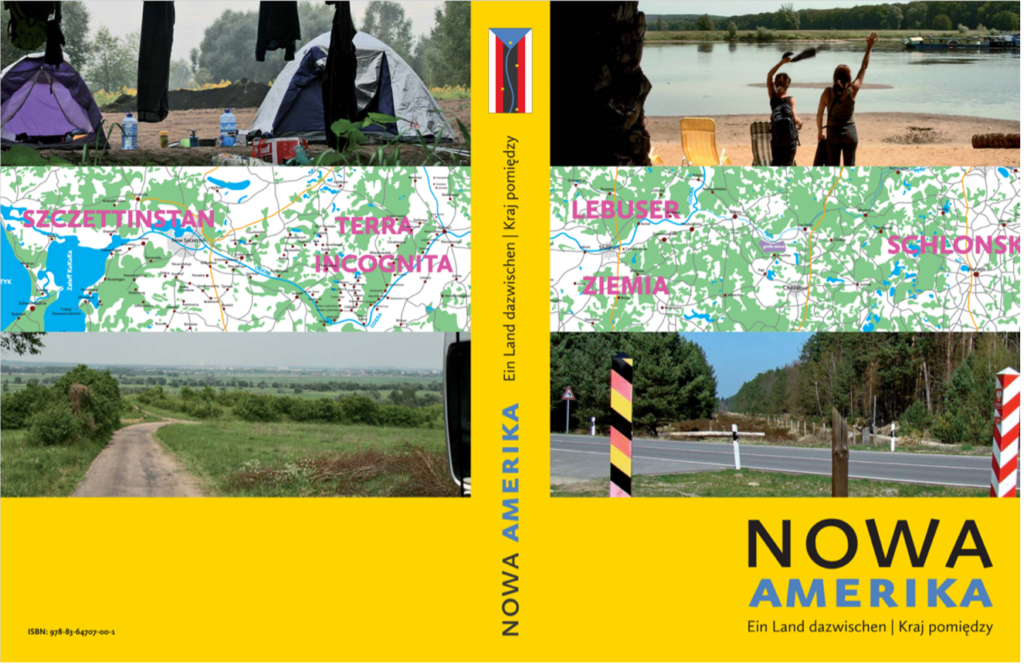

This contribution introduces some of the projects under the umbrella of Nowa Amerika and examines their underlying principles and strategies. By analyzing specific examples (e.g., maps and language), I argue that Nowa Amerika intervenes in the borderland’s temporal and spatial reality and creates new narratives that challenge established political, cultural, and social boundaries. On the one hand, the projects produce a cosmopolitan vision of the borderland by playfully subverting the borders of the nation state: they remap its divisive reality into a shared space, for example, through the creation of new cartographies or by bringing people together to form cross-border networks within the local community. On the other hand, their decided focus on the present and future means that historical context is at times oversimplified or elided. Because a (self-)critical stance is an essential element of contemporary understandings of cosmopolitanism (Delanty), this lack of complexity blurs the cosmopolitan vision. Omissions are for example evident in the way in which the 2014 Nowa Amerika guidebook (Fig. 1 below) represents the project’s founding mythology as well as the history of this borderland in the 20th century. My analysis acknowledges the extensive labor that goes into these projects and their positive contributions to the local community. At the same time, it invites thinking about two larger concerns: first, the tensions and difficulties that are embedded in projects of this scale, as they try to appeal to a diverse audience, and second, the challenges and taboos in the relationship between Germany and Poland.

Since it is difficult to assess the local impact of these projects and to ascertain how many people are actually engaged in them on a regular basis, this contribution focuses primarily on the narrative Nowa Amerika creates about itself in written publications.[5] Furthermore, for over two decades now, Nowa Amerika and Słubfurt have been receiving funding and recognition from German institutions, such as the Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Germany’s Federal Agency for Civic Education. Major funding also comes from various European Union grants, which can be seen as an acknowledgement that the projects foster “international cooperation and integration by de-emphasizing national borders and promoting a transnational sense of ‘European’ identity” (Asher 497).[6] These projects are therefore not only local initiatives but also part of what Azade Seyhan has described as “officially sanctioned” discourse (31).

Disrupted Spaces

The name of Nowa Amerika’s capital Słubfurt is an amalgamation of Słubice and Frankfurt an der Oder, two border towns on the Oder River, about 60 miles east of Berlin. From the Middle Ages until the end of the Second World War, there was only one town here, namely Frankfurt (Oder). After the end of war, the Oder and Neisse Rivers became the new German-Polish border, and Frankfurt was divided. The part on the right riverbank was integrated into the Polish state and renamed Słubice, while the part on the left riverbank soon became part of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). The border remained a point of contention, and even after the GDR officially recognized the new German-Polish border in 1950, and despite the rhetoric of brotherhood that presumably united the Eastern Bloc, the cities remained divided politically as well as in the minds of their inhabitants. After the end of communism, this difficult legacy was not easy to overcome.[7]

Today Słubice has about 18,000 inhabitants, while Frankfurt (Oder) is considerably larger with a population of about 58,000. A bridge that spans some 820 feet connects the two towns. For six decades, i.e., throughout the communist period and before Poland joined the European Union in 2004, the bridge served as an important border crossing point, with a hard national border running through the middle of the Oder River flowing below. After Poland’s accession to the Schengen zone in 2007, the border checkpoints were removed, enabling pedestrians and motorists to cross freely between the German and Polish sides. This openness was briefly interrupted in 2020, when travel restrictions were put in place during the early phase of the Covid-19 pandemic. In spring 2023, some politicians started to call for a reinstatement of stationary border controls to prevent asylum seekers from entering Germany, but for now border practices have not changed for EU citizens.[8] Despite more than a decade of open borders, and some successful collaborations on the municipal and administrative levels, the cities nonetheless still largely function as separate entities, not only politically and administratively, but also culturally and socially. The academic communities connected to the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder) and Słubice’s Collegium Polonicum (a branch of the University of Poznań) are major forces in fostering a closer German-Polish cooperation, but as new additions to the city, even they had a hard time finding their place in the local community.[9]

In the 2010 guidebook Słubfurt: City Guide/ Przewodnik miejski/ Stadtführer (hereafter City Guide), Kurzwelly explains that Słubfurt was conceived to counteract the deep-seated “identity crisis” that was afflicting the inhabitants of Frankfurt (Oder) and Słubice (12). As the book explains, this crisis had its origins in the radical population shifts that accompanied the westward movement of Poland’s borders after the Second World War: at the end of the war, the National Socialists had turned Frankfurt (Oder) into a defensive strongpoint and largely emptied the city of its civilian population. Afterwards, the heavily damaged city initially became a reception center for German expellees from the East and was later settled by people from different parts of the GDR (7, 10). The Germans who had previously lived in the part that became Słubice were forced to leave, and Poles moved in, many of them expellees from Poland’s former Eastern territories that had become part of the Soviet Union. For a long time, Poles in the formerly German regions feared that the Germans would eventually return, leading to what historian Gregor Thum has described as “impermanence syndrome” (171) in his study on Wrocław (formerly Breslau).[10] To counteract this insecurity, the Polish government sought to establish for these regions a Polish identity by referring back to the Middle Ages, when this area had been ruled by the Polish Piast dynasty (Kurzwelly et. al. City Guide 10). When communism fell, narratives were disrupted yet again. Because of the fundamental changes in the political systems of both countries and the subsequent enlargement of the EU, anthropologist Andrew D. Asher has described Słubfurt as the “re-imagined vision of a bi-national and ‘European’ city” (506). Moreover, as I discuss here, it also aspires to overcome national frameworks altogether.

Cosmopolitan Interventions

Figure 1. Cover of the guidebook Nowa Amerika: Ein Land dazwischen / Kraj pomiędzy, Słubfurt e.V., 2014. Cover images by Andrzej Łazowski. Reprinted with permission of Michael Kurzwelly and Słubfurt e. V.

Kurzwelly stepped into this multiply disrupted space not with the goal to build a bridge between Germany and Poland but rather to overcome binary thinking and merge two seemingly distinct spaces into a new and shared space. The City Guide describes Słubfurt as a “city at the border of two countries that do not exist” (107).[11] The 2014 guidebook Nowa Amerika: Ein Land dazwischen/ Kraj pomiędzy (hereafter N.A. Guide) (Fig. 1 above) explains: “The Germans over here, and the Poles over there—we don’t have that here anymore. We are Nowo-Americans with post-Polish, post-German, and many other migration backgrounds. We have established a new space in the in-between space that dissolves the dialectic between two national societies. As Nowo-Americans we feel committed to this new commonality, and we therefore no longer have any German-Polish handshake-performances” (5).[12] The guidebook’s subtitle also refers to Nowa Amerika as a “country in-between,” and one can see how this applies in a double sense: it is a country between two countries, and it occupies a space between an existing and an imagined reality.

Kurzwelly describes Nowa Amerika and Słubfurt as reality constructions (“Wirklichkeitskonstruktion”). For him, reality is always constructed and accordingly, these projects propose an alternative reality in which borders do not exist (N.A. Guide 4, 15). It is important to add that these constructions are not unrecognizable or detached from the existing reality; they are based in and determined by the borderland’s actual conditions, and like the borderland itself, they are constantly changing.[13] These new “post-German” and “post-Polish” spaces are practice-oriented, and they link to real places, locations, and people who physically inhabit the borderland space. Contemporary notions of cosmopolitanism build on the very idea that a universally conceived humanity and world citizenship are deeply entwined with specific, local attachments and self-reflective practices. This complexity has been variously theorized, e.g., as “rooted cosmopolitanism” (Appiah), “regional cosmopolitanism” (Berman), or as a “situated” or “locally inflected,” and “actually existing” cosmopolitanism (Robbins). In the German-Polish context, historian Robert Traba has proposed a cosmopolitan constellation through the concept of “open regionalism” (“otwarty regionalizm”), which follows the motto: “Think universally, act locally!” Its underlying belief is that the active engagement with local conditions and histories leads to a better understanding of oneself, one’s neighbor, and Europe – and even “universal reality” (Loew and Traba 100, translations mine). Importantly, in this contribution, I refer to universalism as a desire for unity in the face of disintegration and crisis, as Daniel Chernilo has argued.[14] Such a sense of fragmentation and conflict is inscribed into borderlands in particularly forceful ways.

Humor and performance serve as two essential tools to Nowa Amerika’s reality construction: humor lowers the threshold to tackle difficult problems (Kurzwelly and Stefański The Message 26), and performance brings the imagined space to life in the existing one. The City Guide states, for example: “Our theater is the space of the city, our actors are all who are present“ (28).[15] These performances, then, are both actions in space and enactments of space: On the one hand, they happen in the borderland: Nowa Amerika’s institutions, projects, and events are located in a particular, if not clearly delineated space that extends out from the real Polish-German border. On the other hand, they are also performances of the borderland that stage the space itself as a complex set of local and global constellations. Following J. L. Austen’s speech act theory, Nowa Amerika creates reality simply by declaring it. The performances address the German, Polish, European, and global present, and they draw attention to the social, cultural, linguistic, and political entanglements that shape our world. The borderland is thus made visible as a fluid and multilayered concept: it is a palimpsest of different histories, cultures, and languages that is constantly changing.

This universal, globally networked thinking, combined with local performance or action, defines the project’s aim to be an open and inviting space. Belonging can be claimed easily by obtaining a Słubfurt ID in a local copy shop or by simply printing it out at home. One can also become a community member in practice, for example by participating in Słubfurt’s “banking system,” where a “ZeitBankCzasu” (literally a “time-bank of time”) helps with the exchange of volunteer services, such as cleaning, shopping for the elderly, or construction.[16] In early 2015 the “ZeitBankCzasu” welcomed asylum seekers, such as a restaurant owner from Damascus, who was not permitted to work while waiting for the approval of his asylum request. He cooked for a Słubfurt event and received German language lessons in exchange for his time (Weiß). More recently, Słubfurt assisted with legal services or helped arrange sanctuary in a local church for asylum applicants facing deportation. A “Free Shop” on the grounds of Nowa Amerika (Fig. 2 below) provides in-kind assistance in the form of clothing and other items, and it offers spaces and community for singing or theater performances (MacGregor).[17] This kind of support and welcoming of newcomers sends an important message in Frankfurt an der Oder, which saw a high level of right-wing extremism in the 1990s (Asher 500) and where the rightwing anti-immigration and anti-EU party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) came in second in the 2021 federal elections (Landeswahlleiter). Similarly, for participants from the Polish side of the border, Słubfurt counteracts the anti-immigrant, anti-EU, and anti-German rhetoric and politics coming from the national-conservative Polish government since 2015.[18]

Figure 2. View of the Nowa Amerika grounds at “Brückenplatz/ Platz Mostowy” in Frankfurt (Oder). The multilingual sign reads: “Bridge Plaza 2.0. This is an open space. Everybody may feel at home here and bring in his/her ideas.” Photo taken by the author, July 2021.

Remapping the Borderland

Nowa Amerika’s spatial interventions in the borderland are especially evident in maps. As Kurzwelly explains in an interview, and as indicated in earlier examples, a main strategy is to mimic and subvert the tools used by nation-states (Kannegießer 00:09:15-00:10:08). This approach also pertains to the creation of maps. While these experiments have no direct political impact, Marta Smolińska has noted with regard to Kurzwelly’s remapping of the borderland that “cartographic imaginations can have performative force and are able to create a counter-hegemonic borderscape not only on the map, but also in people’s mindscapes” (12). Nowa Amerika’s unusual geography reflects this strategy: to locate the country, one must begin by imagining a conventional map of Germany and Poland today. Nowa Amerika stretches along the entire length of the Oder and Neisse Rivers. In the artists’ conception, these rivers constitute “the former German-Polish border” and the country’s “backbone” (Kurzwelly et al. City Guide 17). This backbone is the only non-negotiable (albeit fluid) part of the country’s geography. The once divisive border now holds the new country together, and the former peripheries of two nation states have moved to the center of this new, postnational body.

All the outer limits of this space are flexible, allowing the country to extend like an “amoeba” and sometimes even including the more distant “provinces” of Berlin and Poznań (Kurzwelly et al. City Guide 16). In addition to its fluid and flexible expanse, Nowa Amerika no longer follows the north-south orientation of the Oder and Neisse Rivers.

Figure 3. A map of “Szczettinstan,” one of the four regions of Nowa Amerika, created by Tomasz Stefański. Nowa Amerika: Ein Land dazwischen / Kraj pomiędzy, Słubfurt e.V., 2014, pp. 56-57. Reprinted with permission of Michael Kurzwelly and Słubfurt e.V.

Instead, the conventional map has been turned by 90 degrees so that the Baltic Sea is alternately located in the western or the eastern part of the country. The southern-most tip, where Poland, the Czech Republic, and Germany meet, can now be found in the country’s eastern- or westernmost corner (depending on which map one consults). In Nowa Amerika, the rivers Oder and Neisse thus flow from east to west or from west to east, respectively. The map below shows “Szczettinstan,” one of Nowa Amerika’s four states, and it illustrates a section of this reimagined geography (Fig. 3).

In this new, flexible cartography, the former boundary between East and West is not only unclear, but these notions in themselves are meaningless on a map that does not commit to a specific orientation. This map also rejects the idea of Eastern Europe as the other, thereby dissolving a binary that was invented during the Enlightenment period, when the lands of “barbarism and backwardness” were shifted from northern Europe to the East, as Larry Wolff has argued (5). Kristin Kopp has examined how this long-standing othering of the East has also informed Germany’s discursive colonization of Eastern Europe, and especially Poland, in the nineteenth and twentieth century. Kopp’s analysis includes maps created by German nationalists and National Socialists before and during the Second World War and the cartographic strategies that were used to delineate Polish space and its people as other, chaotic, and inferior (143-178). Such strategies included the use of stark contrasts in graphics or black-and-white images, or the uneven inclusion of cartographic information so that Polish space appeared empty and underdeveloped (138-141). The maps of Nowa Amerika, with their flexible topography and their green, white, and blue coloration and softly outlined spaces, stand in stark contrast to conventional national maps and, still more, subvert the propagandistic German maps that Kopp analyzes.

Language also plays an important role in reshaping these border spaces. The language of Nowa Amerika is “Słubfurtisch,” which consists of alternating between German and Polish while speaking. When the Nowa Amerika map was created, the places on it also had to be linguistically adapted, and for this purpose, a “Commission for Name Changes in the Lands of Nowa Amerika” was established. The renaming of places represents another satirization and subversion of previous nationalist policies, such as the Germanization strategies that the National Socialists had applied to Polish space. After the war, the communist Polish government in turn changed the German names into Polish names (N.A. Guide 18-19, 21, see also Kuszyk 48). Unlike these earlier efforts, when names were either German or Polish, Nowa Amerika’s Commission uses various linguistic strategies to produce hybridized German and Polish place names for this postnationally defined space (see Fig 3 above). For some sites, German and Polish place names were morphed into new words, carefully maintaining diacritical markings, e.g., “Ostbałtyk” (a combination of German Ostsee and Polish Bałtyk) or “Küstrzyn” (Küstrin and Kostrzyn) and “New Szczettin” (Polish Szczecin and German Stettin). The border rivers Oder/Odra and Neiße/Nysa became “Odera” and “Nyßa.” Other names have been translated and recombined, e.g., in the case of “Eisenhutastadt” where the German word Hütte in Eisenhüttenstadt was replaced by the Polish word huta (both meaning foundry in English). Sometimes referents were added to hybridized place names, as is the case with “New Szczettin,” where the adjective “new” is meant to express a similarity to the port city New York in the “old America” in the same way in which “Słubfurt […] corresponds to Washington” (Kurzwelly et. al. N.A. Guide 59). In addition, and as I explain below, Nowa Amerika also brought back place names such as “Hampshire,” “Sumatra,” and “New Yorck,” recalling towns that were established in this area in the 18th century, which disappeared or were renamed after 1945 (10–11).

Nowa Amerika uses maps and language to defamiliarize the borderland and lift it beyond the nation not merely into a transnational space, but into one where national borders have become irrelevant. So far, I have shown that the projects are firmly anchored in the space of the German-Polish borderland. The project’s temporal, i.e., historical, links to this space are much looser, as the next section shows.

No Past? Blurring the Cosmopolitan Vision

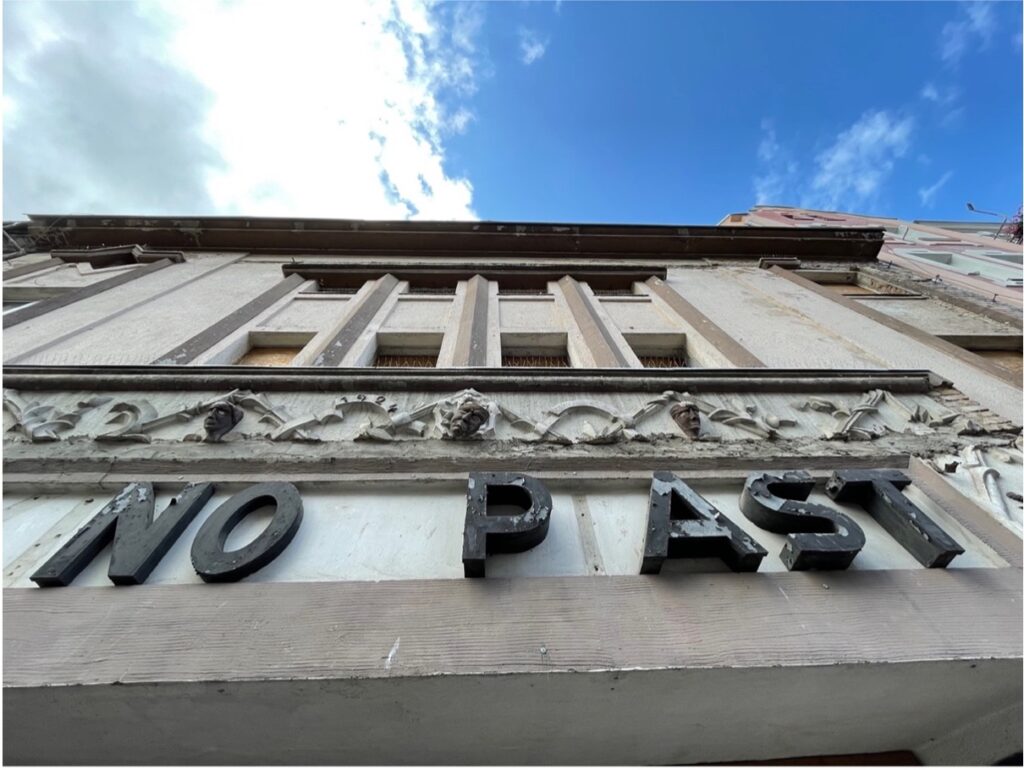

Figure 4: The former movie theater “Kino Piast” in Słubice. Photo taken by the author, July 2021.

The ruins of the former movie theater pictured above (Fig.4) can be seen as a fitting illustration of the entangled and palimpsestic nature of time and space in the German-Polish borderland that Nowa Amerika has chosen as its stage. According to a Polish Wikipedia entry, the “Filmpalast Friedrichstraße” was completed in Frankfurt’s suburb Dammvorstadt in 1924 and, after the Second World War, found itself in the now Polish town of Słubice. In reference to this area’s medieval Polish past under the Piast dynasty, the post-German building was renamed to “Kino Piast,” utilizing the lettering from its former name to spell out “Piast” (“Kino Piast”). After the end of the Cold War, the movie theater changed ownership several times but remained in operation until 2005. In 2012, the owner attempted to demolish the building, leaving only the historic facade. A year later, the Foundation of Cultural Heritage Słubice (Fundacja Dobro Kultury w Słubicach) and the Institute for Applied History (Institut für angewandte Geschichte) in Frankfurt (Oder) organized a film- and cultural festival to help preserve the building’s memory. The letters K and I from the word “Kino” had been removed during the attempted demolition, giving the festival its name: “No Piast” (Abraham-Diefenbach 399-406). Under circumstances that are unclear to me, the letter I vanished from “Piast” sometime around 2017. The current lettering of “No Past,” as well as the movie theater’s story could hardly be a more fitting commentary on the complex and changing history of the German-Polish borderland and the challenges of addressing this past within a European or global present—a weathered facade with many blank spots beneath.

What role does the history of the borderland play in Nowa Amerika? From the beginning, Słubfurt and the projects that emerged from it have clearly focused on the present and future, and this has at times resulted in an uncritical engagement with the borderland. In an article, based on field research conducted between 2004 and 2006, Asher has noted that “Słubfurt tends to de-emphasize the more difficult and potentially sensitive aspects of the cities’ history, and its website makes no mention of the cities prior to Słubfurt’s foundation in 1999” (506). While even the early publications provide some historical context, it is true that this information is kept general and free of sensitive topics such as the Holocaust or antisemitism. Until its relaunch in 2022, this historical context was also difficult to locate on the projects’ websites.[19]

Despite its focus on the present, Nowa Amerika claims deep historical roots, as the name itself highlights. In publications or interviews Kurzwelly and his colleagues repeatedly refer to an eighteenth-century Prussian version of “Neu-Amerika” as a source of inspiration for their postnational borderland. In the 2014 N.A. Guide, the authors note that this reference point may be surprising, given that Prussian power politics under Frederick the Great and the close ties with the Russian Empire also led to the first partition of Poland in 1772.[20] Well aware of the contradiction, they nonetheless elide any closer examination of this history. The authors emphasize that their reference to Prussian history is based purely on its peaceful aspects, and they even give it religious significance:

Frederick the Great has contributed to Poland’s disappearance from the map in the second half of the eighteenth century, and this is clearly something to be condemned. However, he also gained new lands without warfare […]. This unusual history has inspired us to name our new space, which connects the borderland that was divided by the former German-Polish state border, Nowa Amerika: the land of pioneers and those who hunger for freedom; of those who want to create a new social and civil space and who have recognized that this is our Promised Land (15–16).[21]

This narrative of peaceful land reclamation easily seeps into the real world, e.g., when one journalist from the prominent weekly Die Zeit writes: “Of all people, it was the same man who once violently took Silesia for his empire, who in the 1860s developed new lands peacefully by reclaiming the Warthebruch” (Böhm).[22]

This creation myth not only avoids further discussion of Prussia’s foreign policy and expansionism. The idea of “peacefulness” also contradicts the actual ecological injustice that accompanied land reclamation, and which historian David Blackbourn details in his study The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany. Without referring to “Neu Amerika” specifically, Blackbourn explains that in the late 1740s, King Frederick II (Frederick the Great) created a kind of Prussian frontier when he attempted to modernize his state and make new lands habitable through “agricultural improvement and internal colonisation” (33). After the so-called Oderbruch (the marshes around the Oder River) had been made arable by the mid 1750s, the Warthebruch between Landsberg (today Gorzów Wielkopolski) and Küstrin (Kostrzyn) was reclaimed by the early 1780s. In order to attract new settlers to these and other areas, recruitment and promotion focused on “advertising Prussia as a promised land for hardworking immigrants” (51). Descriptions of these new lands drew on images of conquest and exotic wilderness, and this aided in the creation of a Prussian frontier narrative that featured “hardships and pioneer myths” (50) and focused on “endurance” (67).[23]

According to the Nowa Amerika narrative, one area of settlements within the newly cultivated marshlands around the Oder and Warta Rivers was named “Neu Amerika.” This area was no larger than a few square miles, settled by about 15,000 people, and its name expressed the hope for a new beginning that North America embodied for many colonists in the eighteenth century (Böhm). Indeed, historic maps from before the Second World War include American place names such as Louisenwille, Florida, New York, Pennsylwanien, and Philadelphia around the Warthebruch east of Küstrin.[24] In an insightful article, Małgorzata Dąbrowska details the history of this “Warthauer Amerika.” While there is no clear evidence why America might have served as a model, Dąbrowska surmises that it could have been a tribute to the American colonists’ fight for independence or an acknowledgement of Prussian settlers’ involvement in the American War of Independence. What is clear is that one of the settlements created in this context, rather than the entire area, was named “Neu Amerika.” Some settlements gradually disappeared, but those that survived into the twentieth century were renamed after 1945, including Annapolis (Kuczyno), Hampschire (Budzigniew), Maryland (Marianki), Neu Amerika (Żabczyn), and Saratoga (Zaszczytowo) (96).

Old maps document these historical facts, and Kurzwelly explains that more than two hundred years later, this little-known history of exploration and land reclamation served as an inspiration for a series of projects that aimed to remap the German-Polish borderland (N.A. Guide 15-16). Yet, Nowa Amerika’s creation myth romanticizes the land reclamation projects of the 18th century and ignores the problems with settling supposedly “empty” land. Blackbourn shows that land claimed for “Neu Amerika” and other regions had, in fact, been far from empty, and thus the project relied on military force and considerable violence against the local population. Internal colonization was anything but a peaceful operation, and it came at a high cost to humans and the environment. The project destroyed wetlands and fishing villages, displaced hundreds of families and animals, and often produced war-like situations (40, 63–66). Considering the ongoing climate crisis and events such as the mass fish die-off in the Oder-River in 2022 (Oltermann), highlighting these ecological injustices in the history of the region would be an opportunity to link Nowa Amerika’s founding mythology with current concerns. A more nuanced narrative would also be a more consistent one, because questions of sustainability and ecology already play a role, for example in multiple lectures during the Nowa Amerika Congress “Art Saves the World” in 2021 or in community projects, such as “Gardens of Słubfurt.”[25]

Nowa Amerika also evades discussing more recent historical events. While the Nowa Amerika guidebook briefly refers to Germany’s attack on Poland in 1939, the effects of National Socialism as well as the Second World War, this comes across as a ritualized signal to the reader that German crimes against the Poles are not being questioned or omitted. In addition, the publication contains hardly any reference to a past or present Jewish life, which would have disturbed the positive narrative and may have raised some uncomfortable questions about the increase of antisemitism in Germany today but also its presence in Polish society. A search in the electronic version of the over 400-page guidebook for the German or Polish words for “Jew” or “Jewish” returns only seven results, all very brief references, and three of them referring merely to the remnants of Jewish cemeteries. Naturally, there would have been more to say about Jewish life in Nowa Amerika’s various regions, and the cemeteries would have also merited more attention. Karolina Kuszyk relates some of this history in her book, including some details about the Jewish cemetery in Słubice: the site was still largely intact at the end of the Second World War and remained in good condition until 1975, when it was partially flattened to make room for a hotel and restaurant, which became a nightclub at the turn of the millennium. Efforts to restore the dignity of the site and return it to the Jewish community began already in the late 1980s, but they remained unsuccessful until 2002 (312-314). Today, it is one of the oldest surviving Jewish cemeteries in Eastern Europe (311).

The reader of the Nowa Amerika guidebook will also search in vain for words such as pogrom, antisemitism, or antisemitic—all words that would require a discussion of German crimes and the Holocaust as well as persistent antisemitism in German society today. It would also necessitate some discussion of Polish-Jewish relations. For example, the entry on “New Szczettin” mentions in passing that after 1968 no Jews remained in the city, but it provides no hint of the antisemitic campaign that forced many Jews who had initially returned to Poland after the Holocaust to leave the country permanently. Without any context or explanation, the guidebook only states rather obscurely: “Until this day, one can discover there the shadows of the Hasidic hats. But after 1968, there were no more Jews” (150).[26] Besides the lack of perpetrators, the absence of any engagement with Jewish history and culture in the project is striking, considering their significance throughout the entire region.

The omission of certain historical details and complexities makes it not only possible to produce a thoroughly positive image of the borderland; it also helps elevate the project to a quasi-religious mission in which Nowa Amerika can be hailed as a “Promised Land” (Kurzwelly et al. N.A. Guide 16). Such statements are likely intended to be playful and humorous, but this kind of adaptation of the past corresponds with the project’s stated understanding of time and reality. As discussed above, the underlying belief is that any form of reality can be modified or replaced by the construction of a new one (Kurzwelly and Stefański The Message 23-27). Furthermore, this flexibility with regard to reality is coupled with afluid understanding of time. The City Guide explains that Słubfurt was conceived from the perspective of the future, it “grows” out from the future into the present, and in so doing, it also changes our view on the past (Kurzwelly et. al.14). This temporal focus has the problematic effect that the newly created spaces of Nowa Amerika and Słubfurt are largely emptied of their difficult and conflicted pasts, and history becomes a mere backdrop for the performance of an alternate reality. I mentioned in the introduction that Nowa Amerika has already complicated its founding mythology and adopted a more critical view of the American pioneer spirit that inspired it. As the project keeps growing and evolving, it remains to be seen whether its relationship to the historical conditions of the borderland will also be assessed more critically.

Conclusion

Given the divisive political climate and the resurgence of borders everywhere, there is an urgent need to reimagine borderlands as positive spaces. This contribution has shown that Nowa Amerika is driven by a deeply committed group of “regional enthusiasts” who animate others to rethink their relationship to the area, and who play a key role in the development of a regional identity and a positive reimagination of borderlands more broadly (Kinder and Roos 3).While there have been instances of disinterest, criticism, and outright rejection of this transborder approach (e.g., Asher 515-16; Böhm; Kinder and Roos 10-11; Westermann), Nowa Amerika and Słubfurt have nonetheless had a tangible and overwhelmingly positive impact on the German-Polish borderland and its inhabitants (e.g., Kostyrko 95; Hagen). The projects have led to collaborations with international organizations and artists, and they have garnered media attention on both sides of the Oder River (e.g., Böhm; Galka; Tomala). City boosters have used this publicity as well as the concerts, festivals, and tours in their marketing efforts, thereby amplifying the project’s positive socio-cultural effects. However, the cosmopolitan vision created through these efforts is blurred by the omissions and a lack of nuance in the project publications, especially when it comes to discussing the region’s history and Nowa Amerika’s foundation myths.

It cannot be the responsibility of one group of artists and activists alone to address all problems of the past, present, and future. My analysis of the innovative strategies and the omissions therefore also points to two broader questions: first, whether positive reimaginations of borderlands are only possible if violent histories are omitted; and second, whether the creation of new boundaries and exclusions is an inadvertent outcome for any project of this nature. From this then follows the question how violent histories, past injustices, and traumatic experiences can be acknowledged and engaged in a critical way while maintaining the support of the wide audience upon which such projects depend. Addressing the border between the United States and Mexico, Gloria Anzaldúa has reflected on the borderland as a complex system of intersecting systems of oppression, sources of agency, and frameworks of identification, such as nationhood, ethnicity, and gender. It requires continuous negotiation and engagement with contradictions, and this very process has subversive and empowering potential. For Anzaldúa, the place where two worlds collide is an “open wound” (24), but it is also the homeland, a cultural borderland, and a “third country” (25). In this vision, the solution lies not in the marginalization or erasure of painful pasts but in making them productive for the future.

Works Cited

Abraham-Diefenbach, Magdalena. Pałace i koszary: Kino w podzielonych miastach nad Odrą i Nysą Łużycką 1945-1989. ATUT, 2015.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 1987. Aunt Lute Books, 2007.

Appiah, Anthony. “Rooted Cosmopolitanism.” The Ethics of Identity, Princeton University Press, 2005, pp. 213–372.

Asher, Andrew D. “Inventing a City: Cultural Citizenship in ‘Słubfurt.’” Social Identities, vol. 18, no. 5, Sept. 2012, pp. 497–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2012.667601.

Berman, Jessica. “Toward a Regional Cosmopolitanism: The Case of Mulk Raj Anand.” Modern Fiction Studies vol. 55, no.1, 2009, pp. 142–162. Doi: 10.1353/mfs.0.1591.

Blackbourn, David. “Conquest from Barbarism: Prussia in the Eighteenth Century.” The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany, W. W. Norton & Company, 2007, pp. 21–75.

Böhm, Andrea. “Polen: Auf nach Neu-Amerika.” ZEIT Online, 48th ed., 4 Dec. 2013, http://www.zeit.de/2013/48/nowa-amerika-deutsch-polnisches-grenzgebiet/komplettansicht.

Brandenburgische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. “Nowa Amerika / Morgen in Brandenburg.” Brandenburgische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, 9 Mar. 2022, https://www.politische-bildung-brandenburg.de/veranstaltungen/nowa-amerika-morgen-brandenburg.

Chernilo, Daniel. “Cosmopolitanism and the Question of Universalism.” In Routledge Handbook of Cosmopolitanism Studies, edited by Gerard Delanty, Routledge, 2012, pp. 47–59.

David Rumsey Map Center, Stanfort Libraries. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. https://www.davidrumsey.com/. Accessed 7 Apr. 2023.

Dąbrowska, Małgorzata. “Nowa Ameryka nad Wartą: kolonizacja Łęgu Krzeszyckiego w okresie fryderycjańskim (II połowa XVIII wieku).” Rocznik Chojeński, vol. 3, 2011, pp. 91–103, https://bazhum.muzhp.pl/media/files/Rocznik_Chojenski/Rocznik_Chojenski-r2011-t3/Rocznik_Chojenski-r2011-t3-s91-103/Rocznik_Chojenski-r2011-t3-s91-103.pdf.

Delanty, Gerard. The Cosmopolitan Imagination: The Renewal of Critical Social Theory. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Galka, Cezary. “Państwo bez granic, ale z dowodami i paszportami.” PolskieRadio.pl, 5 Aug. 2013, http://polskieradio.pl/art3040_903913.

Hagen, Hans von der. “Leben wie Monty Python in Frankfurt.” Süddeutsche.de, 14 July 2017, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/democracy-lab-leben-wie-monty-python-in-frankfurt-an-der-oder-1.3586449-0.

Halicka, Beata. The Polish Wild West: Forced Migration and Cultural Appropriation in the Polish-German Borderlands, 1945-1948. Translated by Paul McNamara, Routledge, 2020.

Jajeśniak-Quast, Dagmara, and Katarzyna Stokłosa. Geteilte Städte an Oder und Neiße: Frankfurt (Oder) – Słubice, Guben – Gubin und Görlitz – Zgorzelec 1945 – 1995. Arno Spitz, 2000.

Kannegießer, Kristof, dir. 2016. Nowa Amerika. Documentary. Indie Film. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/nowaamerika.

Kinder, Sebastian, and Nikolaus Roos. “‘Szczettinstan’ und ‘Nowa Amerika’ Regionsbildung von unten im deutsch-polnischen Grenzraum.” Eurozine, vol. October 8, 2013, https://www.eurozine.com/szczettinstan-und-nowa-amerika/?pdf. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

“Kino Piast w Słubicach.” Wikipedia, wolna encyklopedia, 11 Apr. 2023, https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kino_Piast_w_S%C5%82ubicach.

Kopp, Kristin. Germany’s Wild East: Constructing Poland as Colonial Space. University of Michigan Press, 2012.

Kostyrko, Olga. Construction of Reality: Symbolic and Social Practice of Michael Kurzwelly’s Slubfurt and Nowa Amerika. 2018. Illinois State University, M.A. Thesis. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2187705139/abstract/37950F4B7A754758PQ/1.

Kurzwelly, Michael, and Tomasz Stefański, editors. Nowa Amerika: Die Botschaft von Nowa Amerika: Wirklichkeitskonstruktion als angewandte Methode/ Przesłanie Nowej Ameriki: Konstrukcja rzeczywistości jako metoda stosowana/ The Message of Nowa Amerika: The Construction of Reality as an Applied Method. Słubfurt e.V., 2020, https://nowa-amerika.eu/book-new-amerika-ks-2/.

Kurzwelly, Michael, et al., editors. Nowa Amerika: Ein Land dazwischen/ Kraj pomiędzy. Słubfurt e.V., 2014, https://nowa-amerika.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/PrzewodnikNowaAmerika.pdf.

Kurzwelly, Michael, et al., editors. Słubfurt: City Guide/ Przewodnik miejski/ Stadtführer. 2010, https://old.nowa-amerika.eu/serwice/przewodniki-guides.

Kuszyk, Karolina. In den Häusern der anderen: Spuren deutscher Vergangenheit in Westpolen. Translated by Bernhard Hartmann, Ch. Links Verlag, 2022.

Landeswahlleiter Brandenburg. Ergebnisse Bundestagswahl, 63 – Frankfurt (Oder) – Oder-Spree. https://www.wahlergebnisse.brandenburg.de/wahlen/BU2021/afspraes/ergebnisse_wahlkreis_63.html. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Loew, Peter Oliver, and Robert Traba. “Die Identität des Ortes. Polnische Erfahrungen mit der Region.” Jahrbuch Polen. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Polen-Instituts Darmstadt, edited by Andrzej Kaluza and Jutta Wierczimok, vol. 23 Regionen, Otto Harrassowitz, 2012, pp. 95-106.

MacGregor, Marion. “Słubfurt: A Welcoming Space for Migrants between Germany and Poland.” InfoMigrants, 30 Nov. 2021, https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/36853/slubfurt-a-welcoming-space-for-migrants-between-germany-and-poland.

“NO PIAST–Festival des verlorenen Kinos.” Institut Für Angewandte Geschichte, https://www.instytut.net/no-piast-festival-des-verlorenen-kinos/. Accessed 5 June 2023.

Oltermann, Philip. “Poland Pulls 100 Tonnes of Dead Fish from Oder River after Mystery Mass Die-Off.” The Guardian, 17 Aug. 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/aug/17/poland-pulls-100-tonnes-of-dead-fish-from-oder-river-after-mystery-mass-die-off.

Opiłowska, Elżbieta. “‘The Miracle on the Oder’: The Opening of the Polish-German Border in the 1970s and its Impact on Polish-German Relations in the Borderland.” East Central Europe, vol. 41, no. 2–3, 2014, pp. 204–22. https://doi.org/10.1163/18763308-04103003.

Rada, Uwe. “Härteste Sprachgrenze Europas.” Interview by Ulf Matthiesen. TAZ, 22. May, 2002, https://taz.de/!1109173.

Ritz, Michael. “Landkartenarchiv: Historische Landkarten, Stadtpläne und Atlanten online.” Landkartenarchiv.de, https://www.landkartenarchiv.de/. Accessed 7 Apr. 2023.

Robbins, Bruce. “Introduction Part I: Actually Existing Cosmopolitanism.” Cosmopolitics: Thinking and Feeling beyond the Nation, edited by Pheng Cheah and Bruce Robbins, University of Minnesota Press, 1998, pp. 1–19.

Schwaß, Robert. “Oberbürgermeister René Wilke lehnt stationäre Grenzkontrollen weiter ab.” rbb Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg, 17 Aug. 2023, https://www.rbb24.de/studiofrankfurt/politik/2023/08/grenzkontrollen-deutschland-polen-asylsuchende.html.

Seyhan, Azade. Writing Outside the Nation. Princeton University Press, 2001.

Smolińska, Marta. “Borderscaping the Oder-Neisse Border: Observations on the Spectral Character of this Current Between Times in Border Art.” Journal of Borderlands Studies, vol. 38, no. 5, Dec. 2021, pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2021.2013295.

Thum, Gregor. Uprooted: How Breslau Became Wrocław during the Century of Expulsions. Princeton University Press, 2011.

Tomala, Jessica. “Kunstprojekt in Frankfurt /Oder: ‘Szanowni Damen und Panowie ….’” Der Tagesspiegel, 14 Sept. 2013, http://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/kunstprojekt-in-frankfurt-oder-szanowni-damen-und-panowie-/8788172.html.

van Laak, Claudia. “Viadrina 500: Die Universität in Frankfurt/Oder feiert ihren 500. Gründungstag.” Deutschlandradio Kultur, 25 Apr. 2006, http://www.deutschlandradiokultur.de/viadrina-500.1001.de.html?dram:article_id=156029.

Weiß, Wioletta. “Energietausch an der Oder.” rbb Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg, Kowalski & Schmidt, 1 Mar. 2015, http://www.rbb-online.de/kowalskiundschmidt/archiv/kowalski-schmidt-010315/energietausch-an-der-oder.html.

Westermann, Jacqueline. “Doppelstadt in Europa: Umstritten und engagiert – unterwegs mit Michael Kurzwelly in Frankfurt (Oder) und Słubice.” Märkische Oderzeitung Online moz.de, 9 May 2022, https://www.moz.de/lokales/frankfurt-oder/doppelstadt-in-europa-umstritten-und-engagiert-_-unterwegs-mit-michael-kurzwelly-in-frankfurt-_oder_-und-slubice-64326715.html.

Wolff, Larry. Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment. Stanford University Press, 1994.

[1] I would like to thank Paula Wojcik, Lidia Zessin-Jurek, Philipp Zessin-Jurek, and the two anonymous peer reviewers for their challenges and suggestions at different stages of this article. I would also like to thank the guest editors, Kristin Kopp and Xan Holt, and the editors of TRANSIT, especially Elizabeth Sun, for all their help in the review and revision process. My sincere thanks also go to the members of the online writing group “DDGC Remote Write-on-Site” for their support. (https://diversityingermancurriculum.weebly.com/ddgc-remote-write-on-site.html)

[2] For more on the “Nowa Amerika Universytät,” and an exploration of its “transpedagody,” see Kostyrko, 63-75. Radio Słubfurt is an independent radio station that broadcasts information and music from Poland, Germany, and the world. Further details and a live stream can be accessed at https://radioslubfurt.de/. The newspaper is published at irregular intervals, and editions are available at https://nowa-amerika.eu/media-2/.

[3] See Kostyrko for an examination of Nowa Amerika and Słubfurt within the broader context of socially engaged art.

[4] The book is trilingual, and the word for “intention” appears in the German and Polish versions of the text but is omitted from the English version.

[5] Relative to the scale and complexity of the project, the number of participants is likely small, as some newspaper reports suggest (e.g., Hagen). Considering the funding sources and the reporting on these projects, it likely also finds more resonance in Germany than it does in Poland.

[6] While recognition within an official European framework provides important funding, Kurzwelly has noted that it also creates a lot of pressure and high expectations (Asher 504).

[7] On the immediate postwar history of the city, see Jajeśniak-Quast and Stokłosa. For a historical view of cross-border cooperation, and a closer examination of the changes in the relationship after 1972, when the border between the GDR and Poland was temporarily opened, see Opiłowska.

[8] Even without stationary border controls, random border police checks have already increased significantly in spring and summer of 2023. Critics, including Kurzwelly and other members of the Nowa Amerika community, have protested the racial profiling underlying these checks (Schwaß).

[9] The Viadrina had been absent from the city for almost two centuries before it was reestablished in 1991. Many of its students and instructors live in nearby Berlin, making it harder for the university to become an integral part of city life. The Collegium Polonicum opened its doors in 2013, and it too appeared to many like it had arrived from outer space (van Laak; Rada).

[10] Historian Beata Halicka describes this area in the postwar period as Poland’s “Wild West.” Karolina Kuszyk examines the post-German heritage of this region.

[11] There are always slight variations between the German, Polish, and English versions of the texts, making conclusive interpretations difficult. In this instance, the Polish text simply states that the city is “on the German-Polish border.” The project in general also has no consistent narrative, e.g., Kurzwelly says that the intention was not to build a bridge, but a main seat of the project is named “Brückenplatz / Plac Mostowy” (Fig. 2). Some publications refer to two countries that do not exist, while others speak only of a city that does not exist.

[12] Translation mine. The original reads: “Hier die Deutschen, dort die Polen, das gibt es nicht mehr bei uns. Wir sind Nowo-Amerikanerinnen und Nowo-Amerikaner mit post-polnischem, post-deutschen und vielen weiteren Migrationshintergründen. Wir haben einen neuen Raum im Zwischenraum gegründet, der die Dialektik zwischen zwei nationalstaatlichen Gesellschaften aufhebt. Als Nowo-Amerikaner fühlen wir uns dieser neuen Gemeinsamkeit verpflichtet, weshalb es bei uns auch keine deutsch-polnischen Händeschüttelperformances mehr gibt.”

[13] Because the projects are constantly changing, Kurzwelly has more recently also referred to them as “reality sculptures” in reference to the “social sculptures” created by artist Joseph Beuys (Kurzwelly and Stefański The Message 27).

[14] According to two major criticisms of the concept, universalism enforces a western-centric normativity and promotes homogenization by dismissing the particular. However, in his examination of the philosophical tradition of universalism and its relation to contemporary cosmopolitanism, Chernilo shows that the idea itself is not exclusive to “Western” thought and that it predates what we today understand as “the West.” He also emphasizes that universalism emerged at a moment of crisis (initially of the Greek polis) and a desire to overcome disintegration (49-51).

[15] Translation mine. The original reads: “Unser Theater ist der Stadtraum, unsere Schauspieler alle Anwesenden.”

[16] See Asher for an analysis of the art project behind Słubfurt’s currency (507-509).

[17] See also Kostyrko for more examples of globally oriented projects and work with refugees (e.g., 59-73, 94-95).

[18] These examples indicate that current events play an important role locally, i.e., in projects, during meetings and events. The group focuses on “doing” over talking, e.g., when planting a community garden or establishing support networks in response to people fleeing the war in Ukraine. Nowa Amerika’swebsite or publications are kept more timeless, avoiding comments on current events or open political statements.

[19] The Nowa Amerika website (https://nowa-amerika.eu) was relaunched around 2022. The new version integrates the different sub-projects that previously had separate websites. The old pages are archived and can be accessed through the menu item “Kurzwelly” on Nowa Amerika’s current website.

[20] Frankfurt (Oder) was at the time part of the Kingdom of Prussia and not part of the territory gained in the partitions.

[21] Translation mine. The original reads: “Friedrich der Große hat dazu beigetragen, dass Polen in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts von der Landkarte verschwand, was klar zu verurteilen ist. Aber er hat auch neue Landstriche ohne kriegerische Handlungen gewonnen […]. Diese ungewöhnliche Geschichte hat uns dazu inspiriert, unseren neuen Raum, der den durch die ehemalige deutsch-polnische Staatsgrenze getrennten Grenzraum verbindet, Nowa Amerika zu nennen, das Land der Pioniere und Freiheitshungrigen, die einen neuen Raum bürgergesellschaftlich gemeinsam gestalten wollen und erkannt haben, dass dies unser Gelobtes Land ist.”

[22] Translation mine. The original reads: “Ausgerechnet der Mann, der seinem Reich einst mit Gewalt Schlesien einverleibte, erschloss in den sechziger Jahren des 18. Jahrhunderts auf friedliche Weise Neuland, indem er das Warthebruch trockenlegen ließ.”

[23] Similar narratives of conquest and colonization would later be applied to territories further east, as examined by Kopp in Germany’s Wild East. After the Second World War, the Oderbruch became part of The Polish Wild West, which Halicka examines in her study of the same title.

[24] Historical maps of this area are available online, e.g., in the David Rumsey Map Center and Michael Ritz’s map collection.

[25] For more on these projects, see https://nowa-amerika.eu/projects.

[26] The original reads: “Bis heute noch kann man dort den Schatten der chassidischen Hüte entdecken. Aber nach 1968 gab es keine Juden mehr.”