“With whose blood were my eyes crafted?”

Critical Concepts of Seeing, Knowing, and Remembering in Philip Scheffner’s and Merle Kröger’s Havarie (2016)1

TRANSIT vol. 14, no. 2

by Roy Grundmann

Introduction

Over the past decade, the splendid vista of the open ocean as it may be experienced, for example, by Mediterranean cruise tourists from aboard a large ship, has been disturbed by an unsettling bit of reality—the presence of stateless migrants floating precariously in small boats in the swells. The experimental non-fiction film Havarie, written by Merle Kröger and directed by Philip Scheffner, revolves centrally around this moment of disturbance. Havarie temporally extends a brief amateur cell phone video that was shot from aboard the cruise ship Adventure of the Seas and that focuses on a dinghy with migrants floating in the Mediterranean hoping to reach the coast of Spain. The film’s minimalist aesthetics turns it into a meditation both on the divisions and the linkages between the migrants in the dinghy and the passengers aboard the Adventure of the Seas, a maritime representative of Euro-American political and economic hegemony. After encountering the video on YouTube, Scheffner and Kröger interviewed its maker, Terry Diamond. Unable to trace the migrants Diamond had filmed, Scheffner interviewed others who had undergone a similar experience. He obtained recordings of the radio traffic of the rescue operation and interviewed crew members both from the Adventure of the Seas and from a containership that had a history of carrying migrants as stowaways. He then used the audio materials to engineer a complex soundscape for the film. Scheffner’s extension of the three-and-a-half-minute video to the length of ninety minutes reflects the approximate time it took the Spanish coast guard to rescue the migrants in the dinghy (Wagner 2016).2

Part of a recent spate of migration-themed films, Havarie charts new aesthetic paths in its attempt to uncouple migration from the status of spectacle. The film has already garnered considerable attention from film and media scholars.3 Several theorists have commented on how its minimalist visuals and layered soundtrack succeed in making spectators develop political solidarity with the migrants rather than mere empathy. Johanne Villeneuve and Debbie Blythe (2020) analyze Havarie’s intricate soundscape as a means of grasping the Mediterranean as a plurivocal aquatic space. Drawing on theories of the disembodied voice and vocal performance, they argue that Havarie’s sonic mapping opens up new ways for spectators to rethink their relationship to migrants as one of ethical cohabitation. Alena Strohmaier and Lea Spahn (2018) discuss Havarie as facilitating a multi-sensory, immersive form of spectatorship that mobilizes viewers’ pre-cognitive engagement with moving image media. This engagement, so the authors claim, prompts spectators to suspend the subject-object divide in their encounter with the on-screen migrant dinghy.

While critical discourse has thus attended to how Havarie compels viewers to engage the migrants in a more sustained way than facilitated by the glut of media and TV news images of migrant boats, some commentators read the film as a meditation on the irreducible differences between the cruise ship and the dinghy. Nilgun Bayraktar, for instance, finds that the stillness of the image, once we link it to clandestine migration, “defies cosmopolitan notions of escape, tranquillity and rest; instead, it elicits a sense of precariousness and uncertainty […].” (2019, 359). And as Anat Tzom Ayalon argues, the fact that the film shows neither the faces of the migrants nor of Scheffner’s interviewees creates an incommensurability between image and voice that prompts reflections on the unknowability of the other, forcing one “to reflect on one’s blindness and deafness while watching the other” (2020, 30).

The common ground I find in these critical takes encourages me to approach Havarie as a kind of meditative template that prompts us to revise the self-other binary with its subtending sets of oppositions. These include white vs. non-white, European vs. non-European, Christian vs. non-Christian, citizen vs. migrant—and, last but not least, present vs. past. Havarie as I shall argue, activates our mnemonic faculty and thus prompts us to put different temporal planes in relation to each other, so as to compare different histories of migration which, despite their specifics, share colonialism and neo-colonialism as framing conditions, and flight and genocide as consequences of those conditions. The site of this activation of viewers’ mnemonic faculty is a particular segment of Havarie that, while frequently noted, has yet to attract sustained analysis—the mid-film pan, during which the camera temporarily relinquishes its gaze onto the migrants and turns towards the cruise ship from where the filming proceeds. The present essay centrally concerns itself with a discussion of this pan and how it subverts the Eurocentric looking relations in which the film partakes. My methodological approach is informed by two of postcolonial theory’s ongoing anti-Eurocentric projects. The first is to break down politically fraught categories of identity that have been shaped by and, in turn, help reinforce, the geopolitical chasm and pervasive power differential between the prosperous West and the Global South. The second is to better understand and promote the reparative role of cultural memory—both in its function of invigorating the bonds between victims of colonial violence, displacement, and deracination and in its potential to create points of contact even between unrelated cultures.

For the Caribbean poet and theorist Édouard Glissant, the need to cope with the loss of traditions and severing of lineages in the wake of the Middle Passage has resulted in the salutary rejection of the very concept of roots. Influenced by Deleuze and Guattari, Glissant substitutes the singular root (with its essentializing Eurocentric baggage) for the rhizome, a web of liminal connections not associated with territorial possession (Glissant, 1990, 144). In related manner, difference for Glissant is not the fixed mark of disparity between two or more essences. He reconceives the processes of cultural formation that are central to anti-essentialist identity through a concept he terms “Relation”—a philosophy of cohabitation which is politically productive because it considers everyone an other (ibid., 169-188). At the heart of Glissant’s rejection of Enlightenment concepts of legibility is his notion of opacity, which is both an ontological and epistemological concept, as Glissant’s exegete John E. Drabinski notes (2019, 12). Consisting of interrelated facets that involve the production of memory without referencing what precedes it (Glissant, 1990, 6-8, 69), the colonized subject’s obscuring of meaning from the colonizer and even from itself (ibid., 66, 153-154, 186, 193), and the uncoupling of epistemic processes from teleologies of certainty and finitude (ibid., 161-186), opacity has an anti-Eurocentric, anti-Enlightenment logic that is central to Glissant’s anti-colonial agenda: “We demand the right to opacity [le droit à l’opacité]. Through which our anxiety to have a full existence becomes part of the planetary drama of Relation: the creativity of marginalized peoples who today confront the ideal of transparent universality, imposed by the West, with secretive and multiple manifestations of Diversity” (Glissant 1989, 2, cited in Drabinski, 13, transl. altered by Drabinski).

How does Glissant’s theory help us compare different histories of migration, such as the Middle Passage and the current migration across the Mediterranean, despite their differences? What are the stakes in subsuming the respective subjects of these migrations under Glissant’s category of “the planetary drama of Relation?” To be sure, the migrants in Havarie have left the African continent on their own accord, in contrast to the Africans of the Middle Passage, who were victims of genocidal colonialist capture. But how free a choice, we must ask, is the decision of subjects who embark on an extremely hazardous, quite possibly lethal sea journey to a new land, where they, even in the slim eventuality of safe arrival, will be instantly encamped and legally, politically, and culturally othered? The difference between the Middle Passage and the Mediterranean migrant crisis is not, I believe, one between forced and voluntary migration. It resides in gradations of force and in both cases this force owes to the effects of colonialism and neocolonialism.4 Correspondences do not end here. The Africans of the Middle Passage were bereft of their identities on their way to becoming slaves; the migrants in Havarie are so called “harraga” who strategically destroy their official identification documents to secure asylum in Spain. It is precisely this voluntarist element that gives their voyage the character of a retracing of a specific consequence of the Middle Passage: both journeys share a contingency between the erasure of the past and the possibility of beginning again in a radically new manner—radical because of the potential to reshape, over time, the body politic and culture of the country of destination.

From the perspective of continental philosophy, the representation of the migrant dinghy in Havarie as a distant and blurry presence certainly constitutes a “crisis of figurability” (Ayalon, 35). But what significance does this crisis assume in the framework of decolonization? The migrants’ decision to define their existence on their own terms by becoming “harraga” accords with how the film lends them a presence that, while visually precarious, is insistent, even quasi-hypnotic. Their distant, blurry, slightly changing position makes them readable either as one or as multiple subjects. The illusion of their visual proliferation implicitly mitigates against the impression of their fragility. They acquire opacity in Glissant’s sense, summarized by Drabinski as “a resistance to certain senses of knowing and understanding that would seek to absorb, reactivate, and possess” (13). In a related manner, Havarie works against assumptions that hold Mediterranean migration to be synonymous with tragedy and death. While it is possible to feel skeptical about the migrants’ fate, the film’s anti-positivist representation of them floating on the open sea and refusing to disappear may also be read as advocating for their right to self-determination—both during their sea rescue and upon being subjected to the vicissitudes of the asylum process that awaits.5 The strategies by which migrants elude deportation certainly partake in the above-mentioned quality of opacity. And the strategies they develop to survive in the interstices of European society warrant reassessing through Glissant’s concept of Relation with its radical postulation that everyone is Other.

As critical concepts, opacity and Relation also pertain to a discussion of Havarie’s mid-film pan, which, as the filmmakers have pointed out, explicitly places the European citizen-tourist and the stateless migrant in relation to each other (Wagner 2016). The film subverts the Eurocentric looking relations it uses by infusing the act of observation with an ethics of accountability. Two questions arise with regard to the pan. First, how does the pan’s execution relate to Diamond’s complex subjecthood as both a white European and a citizen of Northern Ireland, one of the few European countries with a recent history of colonization? Below, I discuss Diamond’s subjecthood and his execution of the pan through Donna Haraway’s theorem of situated knowledges. Second, how does the pan connect the cruise ship rescue scenario to other historical scenarios of migration? I will argue that the pan’s semi-abstract visuals stimulate viewers’ mnemonic faculty in ways similar to those found in certain kinds of modern art. I then discuss the way Havarie prompts viewers’ mnemonic faculty to connect different scenarios of migration, many of which have involved traumatic experiences of flight and statelessness, in terms of Michael Rothberg’s concept of multidirectional memory (2009 and 2011).6

The final section of this essay explores correspondences between multidirectional memory and Glissant’s concepts of opacity and Relation through a case study of traumatic migration. At issue is the history of Jewish refugee ships on the eve of World War II, and specifically the voyage of the MS St. Louis, which left Nazi Germany in May 1939 with Jewish migrants bound for Havana. After Cuba and the U.S. refused to grant the migrants asylum, the ship was forced to return to Europe. It avoided delivering its passengers back into the hands of the Nazis only because it received last-minute permission to dock in Belgium. The St. Louis odyssey is relevant to the present discussion because the ship’s transatlantic trajectory retraces part of the geopolitical coordinates of the Middle Passage and, despite the latter’s political and economic particularities, hints at some underlying commonalities attributable to colonialism and neo-colonialism. The need to diacritically compare the Holocaust and the Middle Passage has long been acknowledged by postcolonial theorists. My discussion will conclude with thoughts on how an analysis of Havarie through Glissant’s and Rothberg’s frameworks can contribute to this project by triangulating the St. Louis voyage and the Middle Passage with the Mediterranean migrant crisis as instances of forced migration.

Terry Diamond’s Video and the Negotiation of the Self-Other Binary

Terry Diamond’s wife had given him the Mediterranean cruise as a wedding anniversary gift (Wagner 2016). The Adventure of the Seas is not a high-end cruise ship. Comparable to a large middle-class hotel, it embodies the transformation of cruising into mass tourism. Of course, when compared to the migrants in the dinghy, Diamond’s privilege as a white middle class European is obvious. Yet, as a citizen of Northern Ireland living in Belfast, Diamond is part of a population that remains under British rule. He belonged to the youth branch of the Irish Republican Army and was directly involved in The Troubles, an armed conflict between Irish nationalists, who fought against Northern Ireland remaining under British control, and Unionists, who sought to maintain England’s power over the region, which England secured through state violence.7 Diamond was unable to escape these punitive conditions—as he mentions in an interview, he spent time in prison and at a young age saw his best friend getting shot by the British police. This experience of helplessness shaped his attitude towards the migrants adrift on the ocean. Near the end of the film, we hear his voice as he describes his response to spotting them in their dinghy:

They were a distance away from the ship. You sort of tried to zoom in to get a clear understanding of what you were actually physically looking at. And then you realized, my God there’s, there’s human beings in this? You know, you start to try and imagine why they’re there. What’s driven them to there. To a certain extent, you start to try and put yourself in their position. But you can never replicate that. You can only assume that it has been something that has been drastic enough to drive people to do that sort of thing (qtd. in Villeneuve and Blythe, 79).

When Scheffner, commenting on Diamond’s response to laying eyes on the migrants, states that all of this was “part of the atmosphere, part of the baggage with which he [meaning Diamond] was looking at the boat (qtd. in Wagner),” what Scheffner presumably means with “baggage” is Diamond’s growing up as part of an externally ruled national minority and his brush with violence used against that minority.

As a European postcolonial subject, Diamond is in a hegemonic position. He enjoys the limited material benefits of decolonization, while his memory of colonial oppression continues to shape his world view. The form of traveling his hegemonic status affords Diamond warrants theorization through a theorem Glissant relates to opacity and Relation—that of errantry. In contrast to discovery or conquest, errantry is a form of traveling that “is no longer the locus of power but, rather, of pleasurable, if privileged, time. The ontological obsession with knowledge gives way here to the enjoyment of a relation; in its elementary and often caricatural form this is tourism” (1990, 19). But Glissant further relates this form of travel to the postcolonial subject’s state of internal exile as someone who remains marginalized because their “solutions concerning the relationship of a community to its surroundings” remain only partially realized. In this context, errantry has a compensatory function. It “tends towards material comfort, which cannot really distract from anguish” (ibid.).

Diamond’s cell phone video registers his state of internal exile. Of particular interest is his professional background as a surveillance specialist. It constitutes a hegemonic form of visual control which, however, appears to be fragile because of the anxious manner in which he trains his cell phone camera on the migrants. By panning to the cruise ship, he then acknowledges his presence to the scenario. Donna Haraway has argued that the way we use vision and the insights we gain from it are never neutral. Aiming to wrest techniques of the observer away from the techno-scientific apparatus of white patriarchy, Haraway wants to replace its disembodied conquering gaze—the “view from nowhere”—with embodied vision and knowledge, or the “view from a body” (Haraway 589). If these “situated knowledges” constitute a new kind of seeing, one that acknowledges its embodied nature and embraces its answerability, the concept helps us to further understand Diamond’s visual acknowledgment of the position of relative power and agency he occupies. “Vision is always a question of the power to see,” Haraway goes on to explain, “and perhaps of the violence implicit in our visualizing practices. With whose blood were my eyes crafted?” (585). Technologies of vision index social orders and practices of visualization: “How to see? Where to see from? […] What to see for? Whom to see with? Who gets to have more than one point of view?” (587).

Diamond first pans to the right towards the ship’s stern, then he pans 180 degrees left for a forward view of its starboard side. Then he pans away from the ship and comes to rest on the dinghy in the middle of the ocean. In its motion, the pan acknowledges, and thereby implicitly destabilizes, the divide between European tourist and African migrant. His documenting the migrants’ existence without objectifying them and his acknowledging his material base without assuming a glibly celebratory position like the selfie pose registers his desire to create a space of ethical cohabitation for him and the migrants. His decision to film the migrants certainly conveys his curiosity about them. Yet, as his quoted comment above indicates, he readily acknowledges his inability to put himself in the migrants’ position. Even more noteworthy is that his limited knowledge about the migrants’ motives for abandoning their own habitat compels him to judge their decision in good faith. His attitude aligns with that of the errant traveler who, in Glissant’s characterization, “plunges into the opacities of that part of the world to which he has access” (1990, 20). Errantry, as Glissant’s comment suggests, is bound up with failure, but here we are to understand failure as a salutary coefficient of rejecting Western epistemology’s totalizing ambitions. By foregrounding elements of risk and contingency, the film transvalues failure’s conceptual implications. This begins with its title, which in German means accident or collision and, more specifically, shipwreck.8 While we know that a shipwreck does not occur, Havarie plays with the possibility that it may.

The Aestheticization of the Pan in Havarie

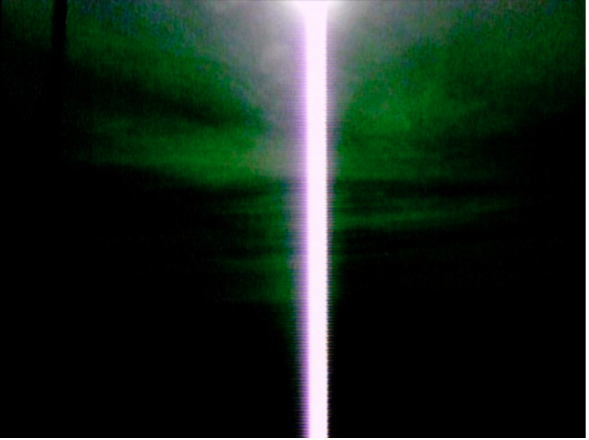

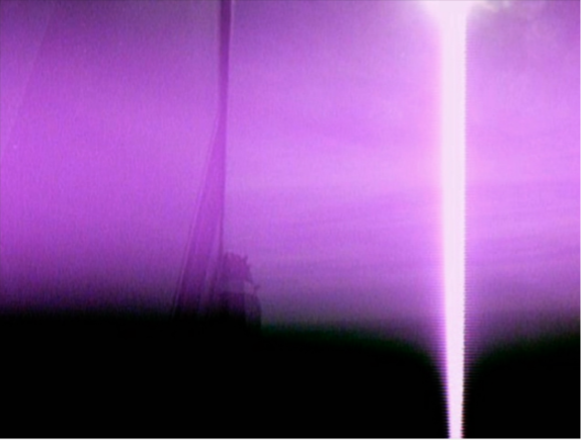

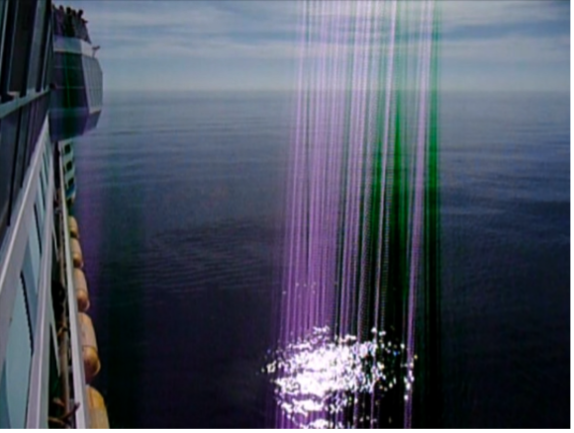

Diamond’s original pan lasts about twenty seconds. In Havarie, it takes eight minutes. Handheld camera movement traditionally functions as indexical proof of the existence and agency of the filmmaker (Hart, 38). Yet, Scheffner’s extension of Diamond’s pan does not merely shift the locus of meaning from one filmmaker (Diamond) towards another (Scheffner). The aesthetic effects produced by the lengthening of the pan stimulate viewers and give maximum interpretive agency to them.9 One of the first things we notice in Havarie’s pan is the subtle doubling of the image of the migrants in the dinghy (Figure 1) and of the tourists on the cruise ship (Figure 2). The unstable phenomenology renders migrants and tourists similarly fragile. This correspondence suggests that both types of passengers share one and the same world in ways that their different positions—the tourists high up on the passenger ship and the migrants way below in their tiny dinghy—seemingly belies. (It is, however, precisely this vertical differential that, as I shall argue in my discussion of the historical case study towards the end, is unstable and that points to a much larger underlying instability).

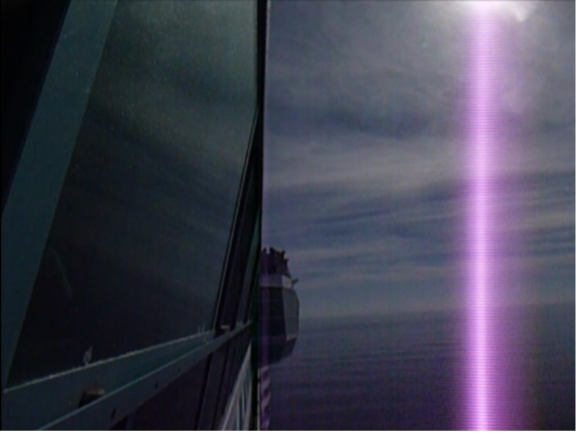

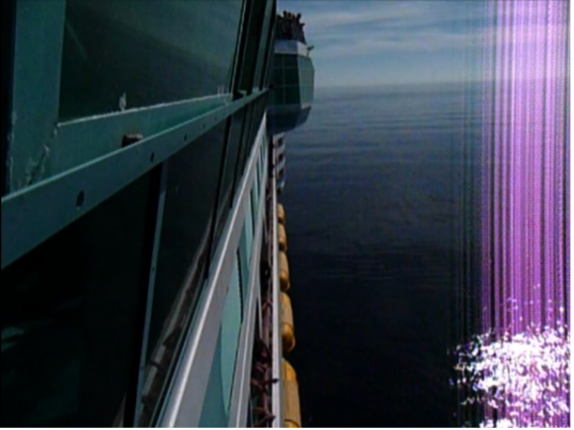

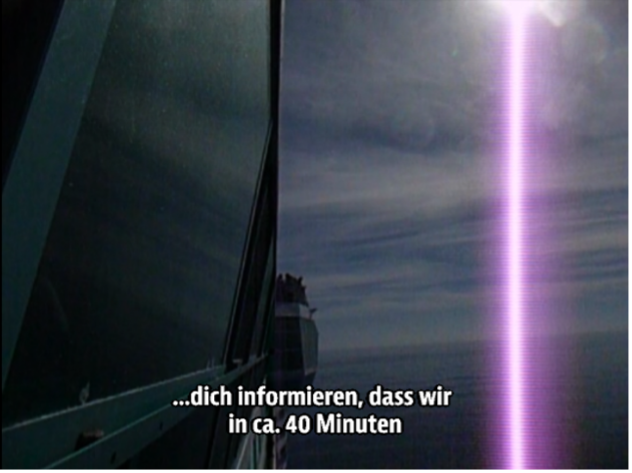

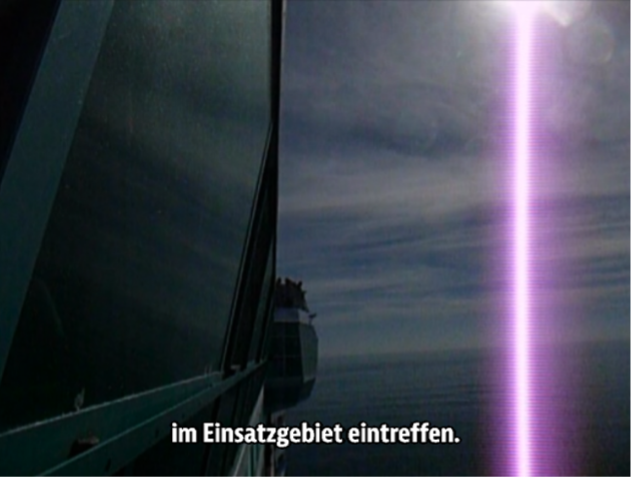

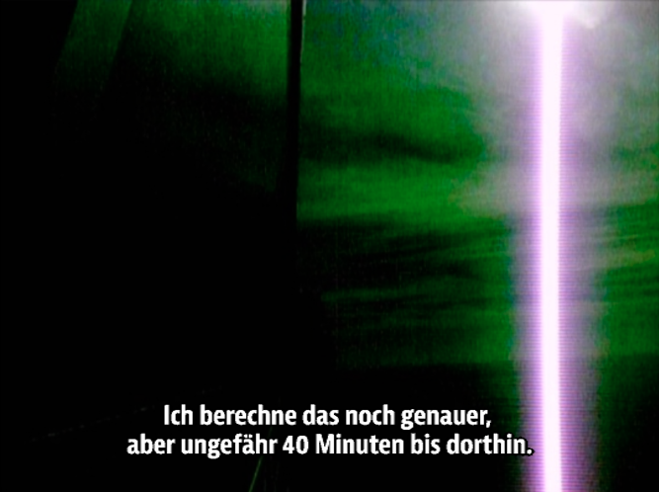

Further, the left pan foregrounds the optical effects generated by the sunlight meeting the lens. These effects inject the realist view of the ship with garish pink and dark green hues. First, we see the ocean and sky being pierced by a flash of light (Figure 3). As the camera moves left, the flash appears toward the middle and brightens, before the image as a whole turns a deep pink (Figure 4). Then the film oscillates between a dark green (Figure 5) and a saturated pink (Figure 6). Then the pink hue becomes less intense and the bright flash moves towards the right hand corner (Figure 7). Before the camera pans away from the cruise ship again, we see what is perhaps the most striking optical effect: a set of light beams that hit the water next to the ship and produce a field of sparkles (figs. 8 and 9). These effects are already fleetingly noticeable in Diamond’s video, but Havarie’s segmentation of the footage into what are almost individual frames elevates them to the order of spectacle and gives us time to take them in.

Reading the extended pan as a series of individual frames—despite the fact that movement between them never fully ceases—has a purpose. My discussion of the spectator’s perception of these slowly moving images is guided by film theory’s recent proposition to consider the mobile frame as a composite of two kinds of movements. One kind refers to profilmic content captured by the camera, while the other refers to the frame’s status as an aesthetic surface (Schonig, 2022, 32 and 2017, 59) that displays movement “as a series of expanding, contracting, and labile configurations” (Bordwell, 1997, 23, cited in Schonig 2017, 64).10 The affinity between camera movement and human perception encourages a reading of the pan as an expression of Diamond’s desire to map pro-filmic reality, a gesture interpretable as his spur-of-the-moment filmic “confession” of being implicated in the power differential between the cruise ship and the migrant dinghy.11 But Havarie allows us to move beyond this common reading of camera movement. Its lengthening of the pan aestheticizes movement as such. This quality of the mobile image accentuates the self-implicating quality of Diamond’s pan but, more importantly, it introduces an element of abstraction that heightens the images’ associative—and, more specifically, mnemonic—potential. To rehearse this process in detail, it is useful to compare Havarie’s aestheticized pan with a form of modern art that has already been discussed for its mnemonic quality—Pop art. As I’ll discuss below, the aesthetic effects of the lengthened pan resemble the aesthetics of certain works of Pop art visually. But before doing so, it is worth addressing how the mode in which Scheffner has appropriated and processed Diamond’s video evinces broader conceptual affinities with Pop art.

Among the qualities Pop art became famous for was its appropriation and eye-popping defamiliarization of realist images circulating in popular culture and news media. Scheffner himself appears to allude to Pop art’s affinities with Diamond’s video when, in a conversation with his interviewer, he describes the effect of the pan on the viewer: “the pan was the moment where I felt ‘Pow!’ […] the pan puts you into a position, and suddenly you understand your position. And that’s the beauty of the image.”12 In the minds of many, “Pow!” invokes the speech bubbles in comic strips, which became the subject of Roy Liechtenstein’s paintings. In my view, however, Havarie’s aestheticization of the pan is most reminiscent of the work of another leader of Pop art, Andy Warhol. What Havarie shares with Warhol’s paintings is the visual referencing and emotional negotiation of anxiety caused by traumatic loss. A prominent example of this are Warhol’s silkscreens of celebrities linked to death, and in particular several paintings showing Jackie Kennedy as a grieving widow. That these paintings bear no iconic resemblance to Havarie is not relevant. Of interest is the way in which, for instance, the silkscreens commemorate a traumatic event in U.S. history through aesthetic surface qualities. While the inflationary volume of media coverage of Kennedy’s assassination had a numbing effect on the public, some have argued that the seriality and formal composition of Warhol’s silkscreens foreground obsession and repetition as cultural conventions and thus constitute a viable alternative to commemorating trauma (Simon 101-118).

Three aspects warrant a comparison between Warhol’s silkscreens and Scheffner’s film: first, both artists have based their works on already existing sources (for Warhol, LIFE magazine’s coverage of the First Lady; for Scheffner, Diamond’s cell phone video). Second, in both cases, the artistic processing of realist source imagery wrests the images away from their circulation in dominant media. By taking the finished work to alternative spaces of reception, Scheffner, like Warhol before him, intervenes in the dominant view of history as constructed by mainstream news. And third, by forgoing a conventional documentary treatment in favor of an experimental one, Scheffner unleashes the hidden potential of Diamond’s video. His slowing down of Diamond’s footage has an effect similar to what we see in Warhol’s silkscreen panels. Particularly in the mid-film pan, the segmentation of the original footage into a series of individual aestheticized images—images notable for their aesthetic surface qualities rather than their profilmic content—produces an emotional charge.13

Just as in Pop art, however, the production of affect in Havarie is complex. The ambiguities of the image (between depicted content and surface aesthetics, narration and stasis, and minimalism and plenitude) generate emotional ambivalence towards the subject represented. Havarie troubles viewers’ conventional role of passive, disengaged witnesses to TV coverage of the Mediterranean migrant crisis by representing its cinematic space as being shared by tourists and migrants and, for that matter, by citizens and foreigners. In doing so, the film prompts viewers to reflect on the contradictory attitudes towards migrants. While European society has traditionally defined itself via discourses of solidarity, many EU member states have developed extensive security apparatuses to protect their borders, a move that has been termed the “Fortress Europe” mentality.14 This contradiction heightens a second one, between the continent’s Christian ideals and the decidedly secular political pragmatism with which the EU fortifies its borders. Havarie subtly foregrounds these contradictions and the moral predicaments they generate by subjecting viewers to the epistemological self-inquiries eloquently articulated by Haraway: with whose blood were my eyes crafted? How to see? Where to see from? Whom to see with?

One way in which Havarie bridges the self-other divide is by projecting the migrants’ precarity back onto viewers. The conduit for this transference is the cruise ship, which takes on ominous connotations because of the pan’s heavy stylization. The frame alternately brightens and darkens, the shaft of light that travels through the image looks like a bolt of lightning, and the beam that hits the water next to the ship like a rain-like cluster looks otherworldly. These flourishes produce an unsettling, even subtly apocalyptic ambience, giving the impression that the ship may be at the center of a disturbance. This impression is reinforced by the audio that plays over these images, a recording of the radio communication between the ship and the Maritime Rescue Unit. We hear a voice telling the Adventure of the Seas that the unit will arrive in about forty minutes (figs. 10-13). Scheffner plays this audio over the images not of the dinghy but the cruise liner, as if the latter is the one in need of attention. This effect is enhanced by audio from the cruise ship listing the number of people on board: “Passengers 3781; crew 1165; altogether 4946 passengers aboard.” The question that arises is not only how the liner contrasts the dinghy, but what both may share.

While this question invites rich speculation, I believe it is most productively pursued if placed within the framework of comparative histories. One point of investigation is whether the fate of the migrants in the dinghy was at some point in the past shared (and may, thus, be shared again) by others, including European cruise travelers. But to address this possibility, we first need to determine how the film establishes a historical mode of inquiry. For this, we return to our discussion of Pop art, which has been said to articulate historical trauma by activating memory. In a canonized argument, art historian Thomas Crow has identified a set of mnemonic processes at work in Pop art and, more particularly, in Warhol’s silkscreens. The key feature of the silkscreen process is its inherently impoverished reproduction of a pre-existing image which constitutes both the image’s look and the foundation for its reproducibility. This link between technique and function and the silkscreen image’s characteristic tension between presence and absence was, so Crow argues, something Warhol seized on in his death-themed celebrity portraits: “The screened image, reproduced whole, has the character of an involuntary trace: it is memorial in the sense of resembling memory, which is sometimes vividly present, sometimes elusive, and always open to embellishment as well as loss” (Crow, 53).

Reminiscent of Pop art’s tendency to keep loss in play with its opposite, embellishment, the aestheticized quality of Havarie’s pan accords with Glissant’s notion of memory as opaque which, in Drabinski’s characterization, comprises “erasure, trace, struggle, proliferation, accumulation, knowing, and the unknowable—all at once” (Drabinski, 20). Further, the opaque quality of the pan’s undulating visuals has affinities to the ebb and flow of mnemonic processes that Michael Rothberg seizes on in his concept of multidirectional memory. While for Rothberg, memory’s dialogic, cross-referential, and labile mode makes it “fundamentally and structurally multidirectional,” dominant media discipline this flow into “competitive memory” to have their historical narratives participate in a zero-sum struggle for validation (Rothberg, 2009, 12). By contrast, the stylized pan of Scheffner’s liminal, experimental film plays into memory’s non-hierarchical nature which, as Rothberg asserts, works through displacement and substitution (ibid).

Displacement and substitution also figure prominently in the mnemonic processing of historical trauma and in the tracing of one trauma through another. But if multidirectional memory performs these mnemonic processes via the “interlacing of memories in the force field of public space” (Rothberg, 13), how exactly can traumatic memories of a specific event be related to Havarie’s pan to the cruise ship? For Rothberg, multidirectional memory attends to “the dynamic transfers that take place between diverse places and times during the act of remembrance” (ibid., 11). This quality accords with certain philosophical understandings of history, particularly Walter Benjamin’s notion of loosely connected historical constellations. These, so Benjamin argues, can on closer inspection illuminate history in a different way. When the historian comes upon certain tensions within a historical constellation, such encounters can produce a burst of associations that crystallize into what Benjamin terms “monads” [Monaden]. According to Benjamin, this approach to historical thinking can “blast open the continuum of history” (Benjamin, 262). It rejects the notion of history as a linear cause-and-effect chain and instead seizes on looser correspondences between different periods and events.

That this approach to history has an aesthetic dimension—in other words, that it invites visualization—can be inferred from Rothberg’s definition of the monad: “Benjamin’s crystallized constellations provide an image of encounter in which different temporalities collide and in which movement and stasis are held in tension (ibid., 44; emphasis mine). But if we were able to read the pan in Havarie as a Benjaminian monad, an aesthetic-discursive site upon which the scenario of another historical trauma of migration flashes up before the viewer, what past event might the pan be said to reference? It is here that the voyage of the St. Louis refugee ship re-enters the picture or, more precisely, our minds.

The Dinghy and the Cruise Liner

The St. Louis, a passenger liner of the Third Reich, sailed to Havana in May 1939 with 937 passengers, most of them Jewish migrants who intended to use Cuba as a waystation to immigrate to the United States. After Cuba rejected them, the St. Louis crisscrossed the Caribbean in the hope that the U.S. might accept its passengers. When the Roosevelt administration declined, the passengers feared they were being taken to German concentration camps, where many of them had already spent time after Kristallnacht. Although the Netherlands, France, Belgium, and Britain eventually agreed to grant asylum to the St. Louis Jews, 254 were caught by the Gestapo in migrant camps after Germany invaded much of Western Europe in 1940 and were eventually deported to Auschwitz and Sobibor.15

Parallels between the fate of the St. Louis Jews and current migrants have not escaped the media. In 2018, coverage of the ship Aquarius, which crisscrossed the Mediterranean with African migrants after suffering rejection from several countries, referenced the St. Louis as a precedent (Focus 2018). Another article linking both ships even features interviews with former St. Louis passengers (Blau 2017). The St. Louis is also invoked in critiques of current U.S. immigration policy. A 2015 article compares Syrians at risk of being denied U.S. asylum to the St. Louis Jews. It, too, includes statements from St. Louis passengers who, despite their ambivalence about the Arab background of many current migrants, declare that world history must never again tolerate human suffering (Miami Herald Archives 2015). A 2015 Time article by a Jewish author titled “The Long, Sad History of Migrant Ships Being Turned away from Ports” places the U.S. rejection of the St. Louis into a broader history of failed appeals of refugee ships to various countries (Rothman, 2015). In 2017, criticism of President Donald Trump’s travel ban against Muslim immigrants and refugees also invoked the St. Louis. One article, titled “How America’s rejection of Jews fleeing Nazi Germany haunts our refugee policy today,” shows a photo of a crying woman aboard the St. Louis as the ship is forced out of Havana (Lind 2017).

Most ships carrying Jewish migrants before World War II were not luxury liners, but cargo ships bound for Palestine. Their small size and dilapidated state resemble today’s African migrant boats more closely than the St. Louis does. Yet, the St. Louis voyage is relevant to the present discussion because, rather than transpiring in conjunction with projections of a future Jewish state, it exemplifies the open-endedly diasporic nature of Jewish culture. The uniqueness of Jewish diaspora is not lost on Glissant in his thinking about errantry:

The persecuted errantry, the wandering of the Jews, may have reinforced their sense of identity far more than their present settling in the land of Palestine. Being exiled Jews turned into a vocation of errantry, their point of reference an ideal land whose power may, in fact, have been undermined by concrete land (a territory), chosen and conquered. (1990, 20)16

Its westbound trajectory to the Americas also prompts us to explore correspondences between the St. Louis voyage and other traumatic instances of forced migration, such as the Middle Passage. This, in turn, may help us develop comparative approaches to studying both the Holocaust and the genocide of enslaved Africans. In The Black Atlantic, Paul Gilroy acknowledges the need to identify “correspondences between the histories of blacks and Jews” (1993, 213). Those correspondences owe to the histories of colonialism and neo-colonialism, which gave rise to the slave trade but, as I will briefly outline below, also exacerbated the Jewish refugee crisis.

The records of the 1938 Conference of the Intergovernmental Committee at Évian-les-Bains, where 32 countries failed to settle on an asylum policy for Germany’s Jews, show that Europe’s colonial powers wanted to relocate Jews far away from Europe while trying to shield their own colonies from large-scale resettlement (Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, 16-30). The representatives of the 17 Latin American nations present at Évian feared that Jewish migrants could alter their countries’ ethnic, religious, and demographic structures (ibid., 25-35) and thus, as their statements indirectly reveal, potentially threaten the neo-colonial elites that ran those countries with European and U.S. backing. The U.S., which initiated the Évian meeting, was aware of these sentiments. President Roosevelt wanted to help Europe’s Jews, but fears of a domestic backlash kept him from increasing existing immigration quotas. Instead, Roosevelt directed his Évian negotiator to subtly encourage other countries to take more immigrants (Roosevelt 1938). During the St. Louis crisis, Cuba became the main focus of these efforts.

The factors behind Cuba’s refusal to grant asylum to the St. Louis passengers reflect nothing so much as Cuba’s century-long neo-colonization by the U.S. After helping Cuba become independent from its colonizer, Spain, the U.S. began to assert influence over the country. It supported the right-wing Colonel Fulgencio Batista Zaldivar, who wielded considerable power over several Cuban Presidents—including Federico Laredo Brú who governed Cuba at the time of the St. Louis crisis—before running a U.S.-backed right-wing dictatorship in Cuba from 1952-1959. One of Batista’s protégés at the time of the St. Louis incident was Cuba’s Director General of Immigration, Manuel Benitez Gonzales, who had been bypassing Cuba’s immigration laws by selling Jewish migrants affordable tourist visas and personally pocketed the profits. When Laredo Brú learned of the scheme, he reinstated Cuba’s regular immigration laws to demonstrate strength against Benitez and Batista and to show he could protect the country. Benitez had closely cooperated with the Hamburg-America Line (HAPAG), which operated the St. Louis and which became a major beneficiary of his illegal profiteering. Company records show that HAPAG in the 1930s systematically boosted Jewish migrant traffic to Latin America, and Batista’s signaling, after Kristallnacht, that Cuba was willing to accept more Jewish migrants, came as a boon to HAPAG.17

HAPAG’s Jewish migrant traffic obviously bears no direct comparison to the slave trade of the Middle Passage. However, both constitute biopolitically motivated transports of large groups of people to the Americas that were organized by European for-profit shipping operators working in cahoots with neo-colonial administrations. Cuba’s rejection of the St. Louis migrants did not simply owe to its often-cited corruption and political intrigues. It must be assessed against its neo-colonization by the U.S.—which helped create domestic power structures that furthered political instability and corruption in the first place— and by factoring in the eagerness of companies such as HAPAG to capitalize on the Nazi’s anti-Semitic politics of expulsion. Those politics, as is well known, were driven by colonialism’s coefficient, racism. The NS State racially othered German Jews so as to encamp them, denationalize them, expel them, and, when that strategy did not yield desired results, exterminate them.

It bears noting that the Nazis did not “invent” racism. Their “Rassenlehre” (race science) was inspired by eugenics, which U.S. scientists used to classify and biopolitically control Black Americans. Gilroy recognizes arguments for the Holocaust’s uniqueness, but asserts that this should not be an obstacle to exploring how Jewish responses to modernity may be relevant to the history of black life. Factors playing a role in these responses include “escape and suffering, tradition, temporality, and the social organization of memory” (213). He reminds his readers that “it is often forgotten that the term ‘diaspora’ comes into the vocabulary of black studies and the practice of pan-Africanist politics from Jewish thought” (205). The involuntary voyage that the St. Louis passengers, after their rejection by Cuba, undertook in the Caribbean and along the coast of Florida does not make them the same as black slaves. But it arguably brings what Gilroy terms “correspondences” between the black and the Jewish diaspora full circle. A pattern emerges whereby certain technologies of racial subjugation, such as eugenics, were developed stateside and became adopted by the NS regime for its own racial discrimination, triggering a large-scale flight to other shores. The centrality of suffering and escape to those experiences of flight and displacement echo certain aspects of the Middle Passage, the phenomenon that laid the foundation for historical conditions in the U.S. that would produce modern technologies of racial classification and subjugation in the first place.

A photograph (Figure 14) shows the St. Louis leaving Havana on June 2, 1939, and taking its passengers into an uncertain future caused by democratic nations’ complicity with Germany’s expulsion of Jews. The photo, if placed side by side with the images of the cruise liner in Havarie, demonstrates the function of Benjamin’s monad as an associative cluster allowing us to place two historical constellations in relation to each other by reversing certain elements between them. In Havarie, it is the dinghy that, juxtaposed to the cruise ship, epitomizes abjectness and despair, for it carries the stateless migrants who are being watched by the cruise passengers. In the photo of the St. Louis, it is the big ocean liner that signifies abjection. The white European refugees it carries are victims of racial anti-Semitism. Deprived of citizenship and rejected by the world, they are being watched by people escorting the liner out to sea in their dinghies or waving them goodbye from ashore. Those onlookers have a rightful place in the world while the ship’s passengers do not. In the same vein, a press photo (Figure 15) that has long been part of St. Louis memory culture shows relatives of the passengers surrounding the St. Louis in small launches and dinghies, hoping to catch sight of their loved ones. The view of the ship’s starboard side eerily corresponds to the view of the starboard side of the Adventure of the Seas in Havarie. But by placing the big passenger ship in the same frame as the dinghies, the press photo accentuates the inverted positions of migrants and citizens that we see in Havarie.

Benjamin’s concept of the monad involves a flash-like moment of recognition that “blasts open” history’s continuum (Benjamin, 262). This flash is what Havarie potentially triggers. The film’s defamiliarization of the cruise liner activates multi-directional memory, which may include images such as the press photo of the St. Louis in Havana harbor, images that have long existed “in the force field of public space,” to use Rothberg’s formulation. The mnemonic potential of images thus resides in their intersection with other memory cultures—including St. Louis memory culture, which has been developing over 85 years and includes the memoirs of the ship’s captain, passenger diaries, popular history accounts, films, novels, cartoons, and installations.18 I do not mean to claim that the St. Louis voyage is the only scene of historical trauma to which Havarie’s Pop art-like images are capable of returning us. At issue are the broader dynamics of debating history by probing correspondences between specific events and placing those events in relation to larger historical constellations. By including films, photographs, and other artifacts that speak of historical events into the dynamics of multi-directional memory, the event in question can become part of what Glissant terms “the planetary drama of Relation.”

A diacritical comparison between genocides can help us understand some underlying causes they may share despite their historical specificities. The trajectory of the St. Louis voyage expands Holocaust studies’ investigation of Nazi anti-Semitism and the world’s indifference to it from Europe to Latin America. This shift markedly qualifies the epistemological status of colonialism within Holocaust studies. Colonialism has traditionally served theorists since Hannah Arendt (1951) to make sense of the “final solution” by locating its roots in Wilhelminian Germany’s genocidal treatment of its colonized African populations (Rothberg 2009). The St. Louis voyage forces us to relate the Holocaust also to the (neo-)colonization of Latin America with its own genocides and histories of forced migration exemplified by, but not exclusive to, the Middle Passage. As my discussion of Havarie and the St. Louis incident through postcolonial notions of opacity and Relation has aimed to show, this change in perspective involves a shift in thinking away from a Eurocentric pensée continentale and towards a postcolonial—in this case, Caribbean—pensée archipélique (Drabinski, 10).19

As Rothberg’s reading of Arendt has shown, continental philosophy engages in a ranking of genocides at the top of which it places the Holocaust. Like all genocides, the Holocaust represents an irrecuperable trauma. But continental thinking, as Drabinski explains (ibid.), reads this irreparable rupture through Eurocentric preoccupations with ontologies and essences. Those preoccupations seem to resurface in the perceived need for the Jewish people to establish roots, whereby the establishment of a concrete territory, as Glissant surmises, has come to compete with the notion of an ideal land as a utopian point of reference. The distribution of the Jewish people across the globe is evidence that there is nothing relativizing or dispossessive about reading the Jewish diaspora through the kind of archipelagic thinking that Glissant formulates in his theorization of the Middle Passage. Glissant, too, conceives of genocide as an irrecuperable trauma. But as his analysis of Caribbean culture has taught him, the way to negotiate the irreversible damages of the horrors of colonial mass murder and forced migration is to continue one’s existence in diaspora’s ever-expanding wake. This creolized mode of existence affords the descendants of genocide’s victims a chance to enter into systems of Relation that have the potential to overcome the destructive effects of colonialism and, by extension, the toxic presence of imperialism on world politics.

It will take many more mnemonic images such as those furnished by Havarie to demonstrate the protean possibilities of entering into Relation. This despite the fact that the frequent invocation of the St. Louis in mainstream press critiques of the “Fortress Europe” and of U.S. immigration policy suggest that a comparative approach to forced migration is already a common practice. The poet Amanda Gorman has recently sketched out correspondences between the Mediterranean migrant crisis and the Middle Passage. Her description is broad enough to allow for the inclusion of the Jewish migrant crisis: “these two occurrences,” Gorman writes, “share the cruelty and global apathy that allowed them. And the result is fundamentally similar: humans denied their homes, their humanity, and, far too often, their lives” (Gorman, 2023).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Nat Modlin and my anonymous peer reviewers for their valuable feedback on this essay.

Works Cited

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Schocken Books, 1951.

Bayrakdar, Deniz, and Robert Burgoyne eds. Refugees and Migrants in Contemporary Art, Film and Media. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2022.

———. “Beyond the Spectacle of ‘Refugee Crisis’: Multi-directional Memories of Migration in Contemporary Essay Film,” Journal of European Studies, vol. 49, no. 3–4, 2019, pp. 354-373.

Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, Schocken, 1968, pp. 253–264.

Butler, Judith. Parting Ways: Jewishness and the critique of Zionism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Blau, Gisela. “Ein Ozean aus Tränen,” Journal21.ch, June 17, 2018. www.journal21.ch/ozean-aus-traenen; accessed April 12, 2020. Author’s translation.

Crow, Thomas. “Saturday Disasters: Trace and Reference in Early Warhol,” in Modern Art in the Common Culture. Yale University Press, 1996.

De Genova, Nicholas P. “Migrant ‘Illegality’ and Deportability in Everyday Life.” Annual Review of Anthropology 31 (2002):419–47.

———. “Spectacles of Migrant ‘Illegality’: The Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36(7) (2013): 1180-98.

Drabinski, John E. Glissant and the Middle Passage: Philosophy, Beginning, Abyss. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

Demos, T.J. The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary During Global Crisis. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Edwards, Aaron, and Cillian McGrattan. The Northern Ireland Conflict: A Beginner’s Guide. London: Oneworld Publications, 2010.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1997 [Poétique de la relation; Paris: Gallimard, 1990].

———. Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays. Translated by J. Michael Dash. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1989.

Gorman, Amanda. “In Memory of Those Still in the Water,” The New York Times, July 15, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/15/opinion/migrant-slave-ship-disaster-poem.html Accessed June 16, 2024.

Grundmann, Roy. Andy Warhol’s Blow Job. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, Autumn 1988, pp. 575–599.

Hart, Adam Charles. “Extensions of Our Body Moving, Dancing: The American Avant-Garde’s Theories of Handheld Subjectivity,” in Discourse Vol. 41, no. 1 (Winter 2019): 37–37.

Huysmans, J. (2000). The European Union and the securitization of migration. Journal of Common Market Studies, 38(5), 751–777.

Koch, Stephen. Stargazer. The Life, World and Films of Andy Warhol. New York: Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd., 1972.

Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees. Proceedings of the intergovernmental committee, Évian, July 5th to 16th, 1938. Verbatim record of the plenary meetings of the committee; resolutions and reports.

Lind, Dara. “How America’s rejection of Jews fleeing Nazi Germany haunts our refugee policy today,” Vox, Jan. 27, 2017. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/1/27/14412082/refugees-history-holocaust; accessed April 12, 2020.

Loshitzky, Yosefa. Screening Strangers: Migration and Diaspora in Contemporary European Cinema. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Miami Herald. “Lessons of the Damned,” Nov. 20, 2015. www.miamiherald.com/latest-news/article230852284.html Accessed May 20, 2020.

Mopo/Focus Online. „Asyl-Streit erinnert an Geschichte der „St. Louis“ vor knapp 80 Jahren,“, July 2, 2018. https://www.focus.de/regional/hamburg/hamburg-hamburg-historisch-er-war-hamburgs-oskar-schindler_id_9187967.html Accessed May 20, 2020.

Ogilvie, Sarah, and Scott Miller. Refuge Denied: The St. Louis Passengers and the Holocaust. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006.

Pollock, Griselda, and Max Silverman. Concentrationary Cinema: Aesthetics as Political Resistance in Alain Resnais’s Night and Fog (1955). London: Berghahn Books, 2011).

Pugliese, Joseph. “Crisis Heterotopias and Border Zones of the Dead.” Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 23(5): 663–79.

Rothberg, Michael. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009.

—-. “From Gaza to Warsaw: Mapping Multidirectional Memory.” Criticism, vol. 53, no. 4, (2011), pp. 523–48.

Roosevelt, Franlin D. Letter to Myron C. Taylor, November 23, 1938. M.C. Taylor Papers, Marist Library.

Rothman, Lily. “The Long, Sad History of Migrant Ships Being Turned away from Ports,” Time, June 9, 2015. https://time.com/3914106/history-migrant-ships-st-louis/ Accessed May 20, 2020.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Simon, Art. Dangerous Knowledge: The JFK Assassination in Art and Film (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996).

Strohmaier, Alena, and Lea Spahn, “Intra-Active Documentary: Philip Scheffner’s Havarie and New-Materialist Perspectives on Migrant Cinema,” Synoptique: An Online Journal of Film and Moving Image Studies vol. 7, no. 2, 2018. https://www.synoptique.ca/_files/ugd/811df8_6311911d8d4d433d941c5f13a78b8e11.pdf. Accessed December 2021.

Umansky, Ellen. “Closing Our Doors,” Slate, March 8, 2017. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2017/03/after-kristallnacht-america-chose-not-to-save-jewish-children-from-the-nazis.html; accesses April 12, 2020.

Villeneuve, Johanne, and Debbie Blythe, “Adrift: Havarie, an Acousmatic Film by Philip Scheffner,” SubStance, vol. 49, no. 152, 2020, pp. 71-92.

Vincent, C. Paul. “The Voyage of the St. Louis Revisited,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 25, no. 2 (Fall 2011), 253-254.

Von Moltke, Johannes. “Ways of Seeing: Ethics of Looking in European Refugee Films.” Corinna Stan and Charlotte Sussman eds. The Palgrave Handbook of European Migration in Literature and Culture. London: Palgrave, 2024. 475-495.

Wagner, Britta. “A Shared Space at Eye Level: An Interview with Documentary Filmmaker Philip Scheffner,” Senses of Cinema 78, March 2016. https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2016/feature-articles/philip-scheffner-interview. Accessed December 2021.

Wolf, Burkhardt, “Im Blick der Stimmen: Fun Ships und Boatpeople in Krögers und Scheffners Havarie,” in Friedrich Balke, Bernhard Siegert, and Joseph Vogl eds., Das Schiff: Archive für Mediengeschichte 20 (Berlin: Verlag Vorwerk 8, 2024), 85-96.

1 The line is from an essay by Donna Haraway (1988).

2 According to Scheffner, the cruise ship captain informed the Maritime Rescue Center in Spain about the migrants and asked if his ship should take them on board, but he was instructed to stay near the dinghy to mark the location of the migrants for the rescue helicopter (Wagner 2016).

3 For an overview of European refugee films and scholarship on them, see von Moltke (2024).

4 Christina Sharpe (2016) speaks of the “black Mediterranean” as a crisis of capital and of representation. “Migrants fleeing lives made unlivable,” Sharpe writes, tend to be misrepresented as “refugees fleeing internal economic stress and internal conflicts, but subtending this crisis is the crisis of capital and the wreckage from the continuation of military and other colonial projects of US/European wealth extraction and immiseration” (59).

5 Havarie’s soundtrack is commensurate with the migrant’s visual opacity. While their voices remain unrecorded and form a potentially problematic structuring absence on the soundtrack, Scheffner adds the voices of other migrants who already arrived on European shores. The soundtrack’s compiling of those voices points to a community of the unknown. By describing those who share in the unknown with others whom they have yet to know, for postcolonial theorists such as Glissant, “the unknown” harbors future potential.

6 Though Rothberg’s concept (2011) figures prominently in Bayraktar’s article on migrant cinema, it does not play out prominently in Bayraktar’s discussion of Havarie.

7 The geographic, cultural, and ethnic proximity between the Irish and the English and the fact that Ireland’s economy and labor force has intersected closely with the British economy makes it difficult to compare Ireland to other British colonies. Yet, Ireland’s war of independence bears similarities to other colonial uprisings. In 1921, the Government of Ireland Act divided Ireland into the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland, with the latter remaining part of the UK. Britain used to endow former colonies with varying states of autonomy, sparking conflicts among and within those regions. In Northern Ireland, descendants of British colonists retained the demographic majority and clashed with Irish nationalists. In 1969, these differences escalated into The Troubles, a three decades-long armed conflict in which unionist militias and British police brutally clamped down on the nationalists. The conflict officially ended with the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which gave Northern Ireland more autonomy, but the history of domination is engrained in the mentality of the Northern Irish. See Edwards and McGrattan (2010). My thanks to Gary Crowdus for his helpful comments on the Northern Ireland conflict.

8 If traced to its Arab roots, “Havarie” also means “error” and “damage” (Strohmaier and Spahn 2018).

9 As Scheffner told Wagner, his extending Diamond’s video to ninety minutes translated into a total frame count for Havarie of 5400 single frames, which makes one frame last about the length of one second, a way of marking time.

10 Since spectating is primarily considered a form of knowledge acquisition that tends to privilege content over form—something Daniel Morgan has termed cinema’s epistemic seduction or the lure of the image (2023)—viewers automatically imbue the camera with an agency they actually cannot verify directly, namely that of creating movement. As Schonig puts it: “Automatically attuned to a set of perceptual depth cues, we see the onscreen movement of space as a movement of the offscreen camera instead of as the movement of space across the surface of the screen […]” (2017, 64).

11 On the double status of Diamond’s pan as both a document and an expression of Diamond’s inner need to assure himself of his own location, see Wolf (2024).

12 Scheffner quoted in Wagner.

13 Havarie also begs comparisons to Warhol’s early films, particularly for their slowed down projection speed. Such films as Eat (1963), Sleep (1964), Blow Job (1964), and Empire (1964) have been discussed as generating ambivalent feelings in viewers that involve both curiosity and boredom. They invite viewers to peruse the image for its concrete contents and its semi-abstract qualities without, however, delivering concrete epistemological “results.” See Koch (1972) and Grundmann (2003), among others.

14 On the “Fortress Europe” phenomenon, see Huysmans (2000), Pugliese (2009), Loshitzky (2010), Demos (2013), Bayraktar (2019), and Bayrakdar and Burgoyne (2022) among others. Citing BBC parlance, Sharpe (2016) explains that the EU aims to stop migrant traffic by “disrupting the business models that make people-smuggling across the Mediterranean such a lucrative trade.” “But the EU,” Sharpe adds, “has no intention of disrupting the other business models, profitable to multi-national corporations, that set those people flowing” (59).

15 See Ogilvie and Miller (2006) and Vincent (2011).

16 Yet, Glissant adds: “This, however, is mere conjecture. Because, while one can communicate through errantry’s imaginary vision, the experiences of exiles are incommunicable” (ibid.)

17 See my forthcoming book On Shoreless Sea: The MS St. Louis Refugee Ship in History, Film, and Popular Memory (SUNY Press, 2025).

18 For an analysis of St. Louis memory culture, see my forthcoming book (see footnote 17).

19 In their discussion of Jewishness and her critique of Zionism, Judith Butler (2012), too, has explored the project of placing different histories of oppression in relation to each other and she, too, explores the value of Benjamin’s concept of mewmory in doing so, though she does not consider postcolonial theory in her deliberations.