Istanbul Next Wave and Other Turkish Art Exhibits: From Governance of Culture to Governance through Culture

Barbara Wolbert

Abstract:

Exhibited from November 12, 2009, through January 17, 2010, three art shows under the common title Istanbul Next Waveintroduced a newly narrated Turkish history of modern art to German audiences. This Turkish intervention, which led to unprecedented curatorial co-operations by established German and Turkish institutions of contemporary art, is juxtaposed with other Istanbul exhibits from the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, such as Urbane Realitäten – Focus Istanbul, berlin . istanbul . vice . versa, and Call me ISTANBUL ist mein Name, in order to examine the controversies, negotiations, and collaborations that defined recent presentations of Turkish artists’ work in Germany. In a diachronic approach focusing on questions of interventions, this article thus inquires into this particular strand of the history of exhibiting contemporary art in Germany, going back to the early displays of works by Turkish artists in the 1970s and 1980s. Layer by layer, it examines the intricate relations between the presentation of Turkish art and the representation of Turks in Germany, which have done more than merely reflecting, shaping, and molding audiences’ receptions, reviews in the media, and public debates at large. The paper aims at evaluating Turkish art interventions in Germany in relation to processes of Europeanization.

Acknowledgements:

I am grateful to all the colleagues who have commented on aspects of my presentation, as well as to Angelika Fenner, the commentator of the panel session “Culture and RePresentation – Turkey and Germany,” which was part of a series of panels initiated and organized by Elke Segelcke and B. Venkat Mani at the 2010 Conference of the German Studies Association in Oakland. I thank the organizers for their initiative and for their great work as guest-editors, as well as journal editor Kurt Beals. For his revisions of my manuscript I thank Richard Gardner.Istanbul Next Wave1 was the collective title of three related exhibitions on display in Berlin from November 2009 through January 2010. These shows introduced contemporary art from Turkey, as well as a newly narrated Turkish history of modern art, to German audiences. One sampled 80 works from the Istanbul Modern collection; another presented works by 17 female artists; and a third featured six explicitly political positions.2 The following illustrations – each set of three representing one of the exhibits in the given sequence – have been used chosen from 16 press photographs representing these three exhibition events.3

These three art exhibitions took place on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Berlin-Istanbul Partnership, and they were connected with Istanbul 2010, Istanbul’s European Capital of Culture program. They were the result of a collaboration of prominent and well-established Berlin and Istanbul art institutions, which had been founded or unified and re-structured in the 1990s. The three Istanbul Next Wave exhibits were on display in the two exhibition halls of the Akademie der Künste – on Hanseatenweg and Pariser Platz – and in the renowned Martin-Gropius-Bau.

The title, providing an arc to span the three exhibitions, was borrowed from the famous American Next Wave event, the Brooklyn Academy of Music Festival,4 and promised the cosmopolitan audience in Berlin an encounter with avant-garde art from Istanbul. There is, however, a second, unintended layer of meaning in this title, which I would like to take as a point of departure for a short history of Turkish art in Germany. This title presents these three shows as just one occurrence in a sequence of Turkish art events in Germany. Indeed, five years prior to Istanbul Next Wave, an earlier wave of Istanbul exhibits had arrived in Germany. Two of these exhibits were on display in Berlin, and one of them, Fokus Istanbul, also took place in the Gropius-Bau. I would like to recall this exhibit of 2005 and take you one more step back in time, to an earlier exhibition of Turkish art in Germany which also took place at one of the Next Wave Istanbul venues, at the Akademie der Künste on Hanseatenweg, more than two decades ago, in 1987.

A First Wave of Istanbul Exhibits and Other Turkish Art Shows in Germany

With a focus on Istanbul Next Wave and these earlier shows, which had been on display at this year’s Next Wave sites, I will chronicle the presentation of Turkish art and its questionable interweaving with the representation of Turkey and of Turks in Germany. Paying attention to issues of symmetry, I will look in particular at the political role of Turkish art institutions and at individual artists’ political activities. Thus, I will address questions of “cosmopolitical and transnational interventions”5 and issues of culture and representation, in particularly devoted to the case of Turkey and Germany. Speaking of “Turkish art in Germany” requires a disclaimer: While German institutions have applied, albeit implicitly, more exclusive definitions in their exhibition practices, I consider works of visual art produced in Turkey or for Turkish sites, works by artists who belong to any ethnic groups within Turkey’s population, and works by artists with Turkish citizenship or of Turkish descent who work within or outside of Turkey. This implies a concentration on modern and contemporary art. The processes underlying the curation, classification and exhibition of works of contemporary art that I examine through exhibitions of ‘Turkish’ art (in the sense used here) may unfold and unravel questions regarding the home, belonging and cultural-political citizenship of an art work itself, which should not be dismissed. However, these questions may not be pursued in this essay on the politics of exhibiting, although I will at times refer to individual artworks. Accordingly, the illustrations of this article will refer not to the artworks themselves, but rather to their representation on catalogue covers, posters, flyers or websites, or to documents of political debates on ‘Turkish art’ in Germany.

The first art event set up in a German museum space and explicitly reaching out to workers from abroad and to their families was part of the Kemnade 74 International in Bochum, the first in a series of music festivals that is still being held today. One of the first art exhibitions that explicitly reflected migrant workers’ experience was Vlassis Caniaris’ one man show Gastarbeiter – Fremdarbeiter, which was also on display in Bochum. Caniaris’ installations were first set up at the gallery of the Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst Berlin, in one of this art association’s first Studio of Realism shows, and went via the Heidelberger Kunstverein6 to the Museum Bochum. This exhibit addressed visually what ten years later would be called the “guestworker system.”7 In order to compensate for the loss of workers from East Germany and Eastern Europe, who could no longer be relied on as an additional workforce to raise the productivity of West German factories once the Berlin Wall had been erected, migrant workers from Turkey and other Mediterranean countries had been hired. Their employment had been set up as a system of rotation; the workers were expected to return to their home countries to reunite with their families after having saved some money abroad. This attempt to contain the migration movements, brought about as a consequence of the cold war economy, paradoxically turned Germany into an immigration destination, after the hiring stop of 1973 ended the period of the initial labor migration jointly facilitated by the West German and Turkish states and marked the actual beginning of Turkish immigration to Germany. The early exhibits dealing with the new reality of guestworkers took place a year after the hiring stop of 1973. While the show in Bochum’s municipal museum addressed migrant workers and their families as audiences, the show in the Kunstvereine rather aimed at including issues of labor migration in West German class struggles and leftist debates.

In the 1980s, exhibits of Turkish art became an outright means of integration policy. Ich lebe in Deutschland: Sieben türkische Künstler in Berlin,8 for example, toured Berlin, Bonn, and Brussels in 1984. Passing over the international art centers of Cologne and Düsseldorf it instead went to the nearby capital of West Germany and the de-facto capital of the European Union. It followed a political itinerary rather than an art route. One of the forewords, not coincidentally written by the Federal Minister of Labor and Social Order, Norbert Blüm, saw the show as “a facilitator of integration.”9 Not only were institutions of cultural politics involved in these art projects; this exhibition of works by artists from Turkey took shape at the intersection of cultural and social concerns.

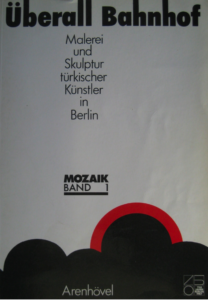

This also applies to the aforementioned show of “Painting and Sculpture by Turkish Artists in Berlin”10 at the Akademie der Künste, one of the later Istanbul Next Wave venues. These exhibitions of the 1980s may be read as a preface to the story of Turkish-German art relations in the first decade of the 21st century. While the actual exhibition catalogue was exclusively in German, bilingual flyers were passed out to invite West Berlin’s multilingual population to a program called “Mozaik.” This program consisted of the art exhibit as well as concerts, theater performances, and a “Türkisches Volksfest,” a public festival on the occasion of Berlin’s 750th anniversary.

The art show thus seemed to be set up as a “contact zone,” to use a term first introduced by Marie Louise Pratt, and later applied to museum spaces by James Clifford. This term denotes a symmetrically structured site within an asymmetrical world.11 Let us take a closer look at this art show in the Akademie der Künste. While in other international exhibits of that time, either in the same exhibition space or in concurrent benchmark exhibitions such as the Documenta,12 we would have seen concept art, video art, and mixed media installations, in the Akademie der Künste we might have been reminded of 1960s exhibits, finding solely paintings and sculptures on display. The content and the titles of many of the works alluded to labor migration. They depicted, for example, a woman in hiding, and a Turkish passport checked by a man in a trench coat accompanied by a German shepherd, road sweepers with dark mustaches in orange uniforms, and women at a conveyer belt.13 The titles of the works contained vocabulary associated with social workers’ discourses, such as “second generation” and “integration.”14

In a “denial of coevalness,” an attitude which Johannes Fabian critiques with reference to anthropologists’ representation of Africa in his famous essay “Time and the Other,”15 these works of contemporary art were framed by a show of Turkish music traditions, Ottoman costumes, and Anatolian rituals.16

Let me finally disclose the title of the exhibit of painting and sculpture by Turkish artists living in Berlin: Überall Bahnhof, or anglicized: Train Station Everywhere. Railway stations were not only the legendary points of guest workers’ arrival and the destination of a journey conceptualized as a round trip; with their international news stands and cafés with long opening hours, they were also the first gathering places for contract workers in Germany. Moreover, this title brings to mind a German expression: “Ich verstehe nur Bahnhof.” “I only understand ‘train station,’” the literal translation of this expression, is an idiom which means “I don’t understand anything at all,” and suggests that the exhibit refers to language barriers. Even more than 25 years after the first Turkish workers came to work in Germany, and almost 15 years after the end of this phase of labor migration, the representation of artists from Turkey maintained the guest worker paradigm.

Rather than a forum for a symmetrical encounter, Überall Bahnhof created a “conflict zone”17 – a zone for Germans to encounter Turks as eternal guest workers. Interested in presenting their work in a distinguished art institution, the artists had followed the curators’ script and played the role of the guest-worker artist, while the curators themselves made use of public funds allocated for cultural and social policy and remained invisible.

Artists’ Political Interventions

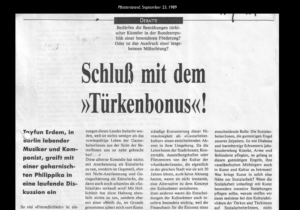

“Schluß mit dem Türkenbonus”18 (“Down with the Turk Bonus!”)19 composer Tayfun Erdem’s polemic essay which appeared in 1989 in the Frankfurt city magazine Pflasterstrand, was the first public outcry against Germans’ appropriation of Turkish artists’ works as a means of social work and a proof of their tolerance. Tayfun Erdem called on organizers, critics, and audiences to take part in symmetrical art encounters and blamed the artists for their acceptance of the lenient applause they earned: “There is no guest-worker culture, just culture! Be critical, and when necessary, merciless, towards the works of artists from Turkey. For only with a discriminating attitude can the foundations for art reception be created and the criteria for art appreciation endure the test of years to come.”20

A year later the House of World Cultures presented Heimat Kunst. “Kunst” means “Art.” And “Heimat” is the place that feels like home. However, Heimat Kunst did not follow the agenda in its title. The artists’ rootedness in their work was not what the exhibition reflected. It would have led to completely different results and perhaps not to an art show. This exhibit, too, featured the artists as migrants. Rather than an integration project, this exhibit was a celebration of diversity. According to one of its curators, “‘[H]ybridity’ which results from the mixture of different cultures is, so to speak, a guarantee for cultural creativity.”21 “The rhetoric of the exhibition spelled out a new era of multiculturalism in Germany,” comments Hito Steyerl in her critical review of the exhibit in 2000, which reveals the political inconsistencies of this exhibit. Reminding us of simultaneous incidents of violence against asylum seekers and their victimization due to a lack of protection, and recalling the often cited opening speech for Heimat Kunst by President Rau in the same year,22 Steyerl points out the discrepancies between German immigration policies and German cultural politics. She addresses the duality of “us,” the indigenous German population (admittedly having also Austro-Hungarian, Russian, or Polish roots), and “them,” obviously the immigrants who came after erection of the Wall and after its fall, and she shows how Rau sided with those Germans, legitimizing Germans’ expectation of foreigners’ assimilation, while, as the patron of the Heimat Kunst exhibit, he embraced diversity. Should we now open the catalogue we would find that a double page was devoted to each artist represented in Heimat Kunst, and that Hito Steyerl was one of them.

Much like Erdem’s article in Pflasterstrand, in her contribution to the “Multicultural Germany” issue of New German Critique Steyerl distances herself from this show. She refuses to act as proof of German tolerance, and rejects the expectation that she should function as Germany’s ambassador for its globalizing markets. The rhetoric of this show of works by artists with migration backgrounds “spelled out a new era of multiculturalism in Germany.”23 The first “wave” of Istanbul exhibits followed this agenda and gave it a transnational turn.

Discussing these more recent changes, I will mention three shows, Call me ISTANBUL ist mein Name, in Karlsruhe; berlin . istanbul . vice . versa, a smaller exhibit in Berlin-Kreuzberg; and Urbane Realitäten – Fokus Istanbul, represented here by the covers of their catalogues. The latter took place in one of the Istanbul Next Wave venues, Berlin’s Martin Gropius-Bau. The show started with a defeat. Almost all the artists from Istanbul withdrew their works. The catalogue included an open letter written by 10 artists – emerging and established – who had pulled out of this show.

The artists blamed the curator, Christoph Tannert, for a lack of transparency when it came to the invitations of the respective artists; and they criticized the “uneven, unequal, biased distribution of funds” to the disadvantage of the artists from Turkey. The organization had indeed remained firmly and exclusively in the hands of the German curator. Moreover, the artists stated an “[o]verall fatigue over exhibitions based on the national identity of the artists.”24

To explain this alleged fatigue, we should take a quick look at the Istanbul exhibit in Karlsruhe. In the catalogue of berlin .istanbul . vice . versa, Vasif Kortun, a key figure in the resistance against the curatorial practice in Fokus Istanbul, wrote about Call me ISTANBUL ist mein Name: “The exhibition was so vulgar and embarrassing that most of the participants said they did not have the nerve to look each other in the face.”25

Although works by Hale Tenger and Gülsün Karamustafa, who had been part of Call me ISTANBUL ist mein Name (this well funded and technically perfect show that took place in the highly ranked media and art institution ZKM) were also selected for Fokus Istanbul, these artists and others chose to forgo the chance to show their work in Berlin’s renowned Martin-Gropius-Bau. While Tenger’s and Karamustafa’s works had been provocative in Turkey during the 1990s, they had become affirmative in front of the audiences in Karlsruhe a decade later. Tenger’s installation alluded to elements of the Turkish flag and Karamustafa’s triptych played with the title of a 1938 Kemalist magazine, Le visage Turc. Like many other pieces on display in Call me ISTANBUL ist mein Name, these works happened not to deal with Istanbul, but with Islam, Kemalism, and Turkishness.

Let me illustrate this using the three most frequently reproduced pictures in the press kit: Sermin Sherif’s photo installation Scarlet Scarf, a still from Belmin Söylemez’ video on mustaches, and Anny and Sibel Öztürk’s installation referring to urban shantytowns in Turkey.26 The combination of these three works of art emphasizes a pattern: The ensemble of all the exhibits pieces added up to a parody of life in Istanbul.

Transnational Art Interventions

Finally, the artists who had signed the letter of protest refused to play the role of “goodwill ambassadors in the EU process of Turkey” (“An open letter…”). This note had been written at a time when the public, both in Turkey and Germany, expected Turkey to become an EU member state in the foreseeable future. The EU-oriented Islamist governmental party, AKP, whose leader had been Istanbul’s mayor, had boosted Istanbul in its attempts to reduce the cultural and political influence of the capital Ankara, the stronghold of its secularly oriented competitor CHP.27 A new museum, the Istanbul Modern, opened, as did many new galleries in Istanbul. Artists and urban activists and other members of Istanbul civil society collaborated in an unprecedented manner and drafted the application for the European Capital of Culture Project, which proved successful. The preparations for the 9th Istanbul Biennial, co-directed by Vasif Kortun and also thematically focused on Istanbul, were in full swing when berlin . istanbul . vice . versa took place in Berlin, which helps us better understand the later concern of the protesting artists. berlin . Istanbul . vice . versa was not only an independently staged show within this first wave of German Istanbul exhibits, it was also a part of a series of cultural events that took place in Berlin under the title simdi now.28 This short festival included 50 productions of visual art, music, theatre, dance, film, and literature, as well as a conference, in 20 venues. The scale and range of the cultural program was new. Art was on display in the Künstlerhaus Bethanien and in the Pergamon Museum; Pina Bausch’s show Nefes, and a performance by the stand-up comedian Cihangir Gümüstürkmen were part of the program; Sezen Aksu had a show in the Tempodrome; pianists Ferhan and Ferzan Önder were on stage in the Philharmonic Hall. Many of the artists involved had already performed or exhibited not only in Turkey and Germany, but in other countries as well. The festival had a state-of-the-art website, which also included a new language: the simdi now page was available in German, Turkish, and English.

The title played with the festival’s new cosmopolitan dimension and acknowledged that Berlin and Istanbul both entail much more than things German and Turkish. With simdi now, Berlin-Istanbul art connections went beyond the bilateralism of German-Turkish relations. This program was sponsored by public and private sponsors, German and Turkish, and realized by nationally and transnationally operating governmental and non-governmental institutions. It had been developed as an initiative of IKSV, the Istanbul Culture and Art Foundation. It was, in fact, the first cultural intervention in Germany of any considerable size which had been officially initiated and organized in Turkey.

Governance Through Culture

Simdi now not only marked a liminal moment allowing new collaborations among artists and cooperative political action, it was also a turning point. Taking up Banu Karaca’s work Claiming Modernity Through Aesthetics. A Comparative Look at Germany and Turkey29, and in particular her article on “cultural policy and the politics of culture in Europe,” this was the moment when “governance of culture had become governance through culture.”30 It was the unease with being an instrument of this politics of culture and the fear of being utilized “as illustrations in the EU integration process” (“An open letter…”) which the artists who withdrew from “Focus Istanbul” had expressed in their letter of protest. A year after simdi now, and two days after Focus Istanbul closed its doors, Austria’s veto blocked Turkey’s next steps towards EU membership.

While the artists’ immediate concern was thus rendered moot, the new politics of culture was sustained: Istanbul as a highly productive mega-city and vibrant juncture of all kinds of traffic, transfer, and exchange in one of the most sensitive areas in the world still needs the arts to achieve the political recognition appropriate to its geopolitical importance. Berlin’s cultural industries not only translate into symbolic capital, they are themselves an important source of economic capital. The European Capital of Culture project, Istanbul 2010 was well on its way and the 20th anniversary of Istanbul and Berlin’s city partnership was approaching. Exhibitions that would highlight this twin-cities-relationship were to be expected. With the appearance of these new actors in the German art world the mode of representation changed: Exhibitions no longer depicted the Turks in Germany; they now represented them. “Darstellung” gave way to “Vertretung.” Rather than Turks’ image in German contexts, it was their cultural political presence – the fact that Turkey and the Turks were represented in Germany – that mattered. While Istanbul sought to obtain control of its assets and position itself with a political voice in Europe and beyond, cultural players in Germany, and perhaps in the art centers of other founding members of the EU, seemed to take their authority for granted. This imbalance was the source frictions and refusals, past and present. For example, it took a long time, and the rejection of several possible partners such as the Kulturprojekte GmbH and Festspiele Berlin, for Cetin Güzelhan, who negotiated on behalf of the City of Istanbul, to find a German partner for his exhibition project and thus become the lead curator of New Wave Istanbul. On the condition that he would evaluate every single piece suggested by his Turkish counterpart, Johannes Odenthal became his German partner. The works of Istanbul artists’ cooperatives as well as transnational grass root collaboratives, which had been included in the simdi now program, were not considered in this program. Studying the current and previous affiliations and functions of the Istanbul Next Wave team, we will see that it consisted of “integrated” curators:31 Istanbul Modern Berlin was co-curated by Levent Calikoglu, the director of the Istanbul Modern, which was founded in the mid-1990s. The earth under my feet, not heaven,32 the show presenting works by 17 female artists, was co-directed by Beral Madra, one of the most influential curators of Istanbul and beyond, who had directed not only the first two Istanbul Biennials, but also several Turkish contributions to the Venice Bienniale. The third show, featuring what was emphasized as “critical art,”33 was co-curated by Johannes Odenthal, who had just left the House of World Cultures to become program chair at the Akademie der Künste. This implied a new thrust of institutionalization on national levels. Istanbul Next Wave thus took a further step in canonizing modern Turkish painting and sculpture and promoting contemporary art from Turkey. But rather than being a transnational cultural project, it was an international one. Istanbul Next Wave, finally, was a show that accorded with the political formula of a “privileged partnership” between Germany and Turkey.

We have traced an exhibition history closely intertwined with changing German immigration politics and the process of Europeanization. To summarize, in the 1970s, a small number of artists, reflecting on the situation of migrant workers, offered political solidarity, and individual museum directors welcomed Germany’s unofficial immigrants as their new audiences. Integrative gestures and political engagement were soon cultivated and tamed: Art became a matter of social politics, which changed paradigms from the integrationist model to multiculturalism. Those patterns of ‘governance of culture’ gave way to a ‘culture throughgovernance,’34 as public art events became conducive to the process of Europeanization. In all of these stages artists intervened; their acts of protest and resistance made the role of the art in immigration politics and later European integration politics visible. Art exhibits now became apparent as “conflict zones.”35 This was the condition under which two ‘waves’ of Istanbul exhibits, five years apart from each other, took place in Berlin and other German cities, when globalization spurred new, wider circulation of artists, art works, and audiences.

The comparison of these two series of Istanbul exhibits exposed the parallels of German immigration and European integration politics. The first one – EU membership within reach – brought about and reflected a moment of symmetry: Following a Turkish initiative, governmental agencies and national and transnational members of civil society, among them many artists, joined forces and entered the Berlin-Istanbul art circuit with Simdi Now. The anticipated partnership materialized in this festival, which was the framework for one of the first Istanbul exhibitions in Germany, shortly before this prospect of Turkey’s EU membership evaporated. The process of canonization and consecration of modern and contemporary art from Turkey in Germany continued. Turkey’s exclusion from the EU enlargement process, however, brought back paternalistic patterns of partnership, which had shaped cultural politics with regard to Turkish art in Germany. It now became once again a feature of politics of culture, which became manifest in the making of Istanbul Next Wave.

Works Cited

Aksoy, Mehmed. Zweite Generation. 1987.

Asaf, Hale. Natürmort / Stilleben. 1928-1930.

Becker, Howard S. Art Worlds, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1982.

Berksoy, Semiha. “Zümrüdüanka” Otopotre / “Phönix,” Selbstprotrait. 1997.

Blüm, Norbert. “Integration vollzieht sich nicht nach Lehrbüchern” in Künstlerhaus Bethanien, ed. Ich lebe in Deutschland. Sieben Türkische Künstler in Berlin. Berlin 1984, 8.

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Bozdogan, Seyyit. Rebhuhnjagd. 1987.

Bozdogan, Seyyit. “Willst Du Meine Arbeit Haben?” 1987.

Castles, Stephen: “The Guestworker in Western Europe. An Obituary. International Migration Review. Vol. 20, No. 4 (Winter, 1986), pp 761-778.

Clifford, James. Routes. Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1997.

“Documenta Archiv für die Kunst des 20. Und 21. Jahrhunderts”. http://documentaarchiv.stadt-kassel.de/ (accessed April 3, 2011). Duben, Ipek. Triptychon. 1981.

Erdem, Tayfun. “Schluß Mit Dem ‘Türkenbonus’.” Pflasterstrand. September 23 (1989).

—. “Down with the Turk Bonus.” Deniz Göktürk, David Gramling, and Anton Kaes, Germany in Transit. Nation and Migration 1955-2005. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007, 437-440.

Eyüpoglu, Bedri Rahmi. Han Kahvesi / Kaffeehaus. 1973.

Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other. How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983

Gürman, Altan. Montaj 4 / Montage 4. 1967.

Ilgaz, Gül. The Struggle. 2008.

Karaca, Banu. “Governance of or through Culture? Cultural Policy and the Politics of Culture in Europe.” Focaal – European Journal of Anthropology 55 (2009): 27-40.

—. Claiming Modernity through Aesthetics: A Comparative Look at Germany and Turkey. PhD. Thesis. CUNY 2009.

—. “Governance of or through culture? Cultural policy and the politics of culture in Europe,” Focaal – European Journal of Anthropology 55, 2009, 27-40.

Karamustafa, Gülsum. Le visage Turc 1998.

Kortun, Vasif. “Istanbul as a Heavyweight Global City.” berlin . istanbul . vice versa. Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin 2004, 28.

Künstlerhaus Bethanien, ed. berlin . istanbul . vice versa, Istanbul Kültür ve Sanat Vakfi, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin 2004.

“Kunstvereine in Deutschland”. http://www.kunstvereine.de/ (accessed April 3, 2011).

Lavaziano, Alex, Corinna Mein, and Martin Sökefeld. “To Be German or Not to Be … Zur “Berliner Rede” Des Bundespräsidenten Johannes Rau.” Ethnoscripts Year 3, Issue 1 (4). Identitäten und Ethnizität (2001).

Moral, Sükran. Kiyamet / Apokalypse. 2004.

Noyan, Nazli Eda. From: Ince Ince Isledim / Finely Embroidered. 2008.

“Offener Brief einiger Künstler und Kuratoren an alle betreffenden Künstler im Zusammenhang mit der Ausstellung Urbane Realitäten: Focus Istanbul / An Open Letter Written by Some Artists and Curators from Istanbul to All Concerned Artists Regarding the Exhibition Urban Realities: Focus Istanbul / Bazi Sanatci Ve Kuratörlerin Urban Gerceklikler: Fokus Istanbul Sergisine Iliskin Ilgili.” Urbane Realitäten: Fokus Istanbul. Martin Gropius-Bau Berlin 9. Juli – 3. Oktober 2005. Ed. Künstlerhaus Bethanien GmbH. Berlin, 2005. 17 / 22 / 26.

Önürmen, Irfan. New Baghdad Museum. 2007.

Öztürk, Anny and Sibel. A Better World Lies in Front of Me. 2003.

Rau, Johannes. “Ohne Angst Und Träumereien: Gemeinsam in Deutschland Leben. Berliner Rede Im Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt.” Berlin 2000.

Semircioglu, Gülay. Töre / Ritual. 2006.

Sherif, Sermin. Scarlet Scarf. 2001.

Soeffner, Hans-Georg. The Order of Rituals. The Interpretation of Everyday Life. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1997.

Söylemez, Belmin. Biyik/The Moustache. 2000.

Steyerl, Hito. “Gaps and Potentials: The Exhibition ‘Heimat Kunst’ – Migrant Culture as an Allegory of the Global Market.” New German Critique 92. Special Issue: Multicultural Germany: Arts, Media and Performance (2004): 159-68.

Tenger, Hale. I Know People Like This II. 1992.

Vogel, Sabine. “Dort, Wo Du Nicht Bist, Wohnt Das Glück.” Heimat Kunst. Ausstellung Im Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt. 1. April Bis 2. Juli 2000. Ed. Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Berlin, 2000. 5.

Weibel, Peter, Roger Conover, Eda Čufer, ed. Call me Istanbul ist mein Name. Ernst Wasmuth Verlag Tübingen Berlin und ZKM, Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie Karlsruhe 2004.

- The full title of the exhibit was Istanbul Next Wave: Simultaneity – Parallels – Opposites. Modern Contemporary Art from Istanbul. ↩︎

- See http://www.adk.de/istanbul_next_wave/Englisch.html; The image on this website is a detail of Gül Ilgaz. The Struggle, 2008. Inkjet pigment print 50 x 210 cm. ↩︎

- Here the proportions of the illustrations on the 2-page tableau of press photo are kept; the sizes of these illustrations do not relate to the proportions of the sizes of the actual art works. ↩︎

- Information from a conversation with Dr. Johannes Odenthal, Akademie der Künste, Program Director, on January 7, 2010. ↩︎

- See B. Venkat Mani’s and Elke Segelcke’s call for papers, which this essay responds to. ↩︎

- The NGBK and the Heidelberger Kunstverein are member-supported non-profit art associations, which exist in almost all German towns and cities to show, discuss and promote contemporary art. See: http://www.kunstvereine.de. ↩︎

- See for example: Stephen Castles, “The Guestworker in Western Europe. An Obituary.” International Migration Review. Vol. 20, No. 4 (Winter, 1986), pp 761-778. ↩︎

- “I live in Germany: Seven Turkish Artists in Berlin,” – translation, B.W. ↩︎

- Norbert Blüm. “Integration vollzieht sich nicht nach Lehrbüchern” in Künstlerhaus Bethanien, ed. Ich lebe in Deutschland. Sieben Türkische Künstler in Berlin. Berlin: Künstlerhaus Bethanien 1984, 8. ↩︎

- This was the descriptive subtitle of this exhibit. ↩︎

- James Clifford, Routes. Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997, 192. ↩︎

- Documenta 8, a show of painting and sculpture by artists from Turkey that took place the same year in the Akademie der Künste, was particularly acclaimed for its video works and its performances. The “Documenta” is a popular show of contemporary and modern art that takes place every fifth summer in the city of Kassel, turning this German city into a center of the art world. See http://documentaarchiv.stadt-kassel.de/. ↩︎

- Seyyit Bozdogan, Rebhuhnjagd, 1987, Oil on Canvas, 170 x 135 cm, Seyyit Bozdogan, “Willst Du meine Arbeit haben?” 1987, Oil on Canvas, 185 x 150 cm, Azade Köker, Fließband, 1987, Terracotta, 220 x 360 x 60 cm. ↩︎

- Mehmet Aksoy, Zweite Generation, 1987, Bardilio imperial marble, 190 x 115 x 45 cm; Ergin Inan, Integration, 1987, Color drawing on hand made paper. ↩︎

- Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other. How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press 1983, 35. ↩︎

- This show was entitled Szenen aus dem türkischen Leben. It took place in the Akademie der Künste next to the exhibit of contemporary painting and sculpture. ↩︎

- Here I abbreviate an expression which James Clifford uses to describe a situation in a museum that, hosting a controversial show featuring colonial perspectives, “became an inescapable contact (conflict) zone.” See Clifford 207. ↩︎

- Tayfun Erdem. “Schluß mit dem ‘Türkenbonus,’” Pflasterstrand (September 23, 1989). ↩︎

- Tayfun Erdem. “Down with the Turk Bonus.” Deniz Göktürk, David Gramling, and Anton Kaes, Germany in Transit. Nation and Migration 1955-2005. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007, 437-440. ↩︎

- Ibid., 440. ↩︎

- Sabine Vogel, “Dort, wo Du nicht bist, wohnt das Glück,” in Heimat Kunst. Ausstellung im Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 1. April bis 2. Juli 2000, Berlin, 5. The catalogue was entirely in German; translation of the quotation by B.W. ↩︎

- Johannes Rau, “Ohne Angst und Träumereien: Gemeinsam in Deutschland leben” Berliner Rede im Haus der Kulturen der Welt, May 12, 2000. See: http://www.bundespraesident.de/Reden-und-Interviews/Reden-Johannes-Rau-,11070.11961/Ohne-Angst-und-ohne-Traeumerei.htm. See also: Alex Laviziano, Corinna Mein und Martin Sökefeld: “To be German or not to be… – Zur ‘Berliner Rede’ des Bundespräsidenten Johannes Rau,” Ethnoscripts, Year 3, Issue 1. (4/2001). ↩︎

- Hito Steyerl, “Gaps and Potentials: The Exhibition Heimat Kunst – Migrant Culture as an Allegory of the Global Market.” New German Critique92, Special Issue “Multicultural Germany: Arts, Media and Performance,” 2004, 159. ↩︎

- “An open letter written by some artists and curators from Istanbul to all concerned artists regarding the exhibition ‘Urban Realities Focus Istanbul.’” Künstlerhaus Bethanien GmbH, ed. Urbane Realitäten: Fokus Istanbul, Martin Gropius-Bau Berlin, July 9 – October 3, 2005, 22. ↩︎

- Vasif Kortun “Istanbul as a Heavyweight Global City” in berlin . Istanbul . vice . versa, Istanbul Kültür ve Sanat Vakfi, 28 August – 12 September 1972, Berlin, 21. ↩︎

- Photo from Sermin Sherif, Scarlet Scarf (2001), 45 parts, 40 x 50 cm; still from Belmin Söylemez, Biyik (The Mustache) (2000), Betacam Video, 25:40 min; photo from Anny and Sibel Öztürk, A Better World lies in Front of Me (2003), Installation. ↩︎

- AKP: Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, the Justice and Development Party, founded in 2001. CHP: Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, the Republican People’s Party, founded in 1924. ↩︎

- “Simdi” is the Turkish word for “now.” ↩︎

- Banu Karaca, Claiming Modernity through Aesthetics: A Comparative Look at Germany and Turkey. PhD. Thesis. CUNY 2009 ↩︎

- Banu Karaca, “Governance of or through culture? Cultural policy and the politics of culture in Europe,” Focaal – European Journal of Anthropology 55, 2009, 27-40; here, 27. ↩︎

- Becker uses this qualification with regard to artists who “have the technical abilities, social skills, and conceptual apparatus to make art” (Becker 1982: 229) and who are “well-adjusted to an art world” (Becker 1982: 230). While I do not find Howard S. Becker’s discrimination between the “maverick,” the “folk artist,” and the “integrated professional” analytically helpful, I apply his term “integrated professional” for its descriptive qualities. Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1982. ↩︎

- “Boden unter meinen Füßen, nicht den Himmel.” ↩︎

- “Sechs Positionen kritischer Kunst aus Istanbul – Six Positions of Critical Art from Istanbul.” ↩︎

- Karaca, “Governance of or through culture?” 27. ↩︎

- Clifford 207. ↩︎