From Colonial to Neoliberal Times: German Agents of Tourism Development and Business in Diani, Kenya

TRANSIT vol. 10, no. 2

Nina Berman

Abstract

This essay traces the role of Germans in various economic developments on the Kenyan coast over the past fifty years, focusing on one of Kenya’s most prominent tourism resort areas of Kenya, the Diani area located south of Mombasa. When tourism development began in earnest in the 1960s, German, Swiss, and Austrian entrepreneurs played a crucial role in pioneering the kind of enterprises that became the hallmark of coastal tourism—upscale hotels, restaurants, bars, discotheques, safari businesses, and diving schools. Reviewing the developments in Diani provides insight into neoliberal transnational economic transactions that presently occur in many areas of the world. Germans take part in these developments not only as representatives of large corporations or agents of state-funded development aid, but also as individual entrepreneurs. The discussion first sketches the setting in which these interactions take place, and then reviews the stages and various dimensions of German economic activities in Diani, namely developments in the area of tourism, small businesses, and real estate. The concluding section considers the effects of the German activities with regard to local culture and landownership, as examples of current global neoliberal developments. Acknowledging the impact of individuals investors, managers, and entrepreneurs through this case study of German activities in Kenya sheds light on lesser-known dimensions of globalization, dimensions that include an increasing north-to-south migration and new forms of cross-cultural hierarchies and collaborations.

Introduction

This essay traces the role of Germans in various economic developments on the Kenyan coast over the past fifty years, focusing on one of Kenya’s most prominent tourism resort areas, the Diani area located south of Mombasa. When tourism development began in earnest in the 1960s, German, Swiss, and Austrian entrepreneurs played a crucial role in pioneering the kind of enterprises that became the hallmark of coastal tourism—upscale hotels, restaurants, bars, discotheques, safari businesses, and diving schools. (For the sake of convenience and because of their significant cultural similarities, I refer henceforth to German-speaking Germans, Swiss, and Austrians collectively as “Germans”). Reviewing the developments in Diani provides insight into neoliberal transnational economic transactions that currently occur in many areas of the world, and that, in the case of Kenya and many other countries, perpetuate processes of land alienation that began during the colonial period. Germans take part in these developments not only as representatives of large corporations or agents of state-funded development aid, but also as individual entrepreneurs. Ethnographic research on the effects of tourism and lifestyle and amenity north-to-south migration has brought to light the impact of US citizens on communities in Central America and the Caribbean and that of northern Europeans in southern Europe and the Middle East. Little, however, is known about the actions of small-scale investors and entrepreneurs, especially in the various countries of Africa. Acknowledging the impact of individuals investors, managers, and entrepreneurs through this case study of German activities in Kenya sheds light on lesser-known dimensions of globalization, dimensions that include an increasing north-to-south migration and new forms of cross-cultural hierarchies and collaborations.[1]

In this discussion, I first sketch the setting in which these interactions take place, and then review the stages and various dimensions of German economic activities in Diani, namely developments in the area of tourism, small businesses, and real estate. The concluding section considers the effects of the German activities with regard to local culture and landownership, as examples of current global neoliberal developments.

The Setting: Diani

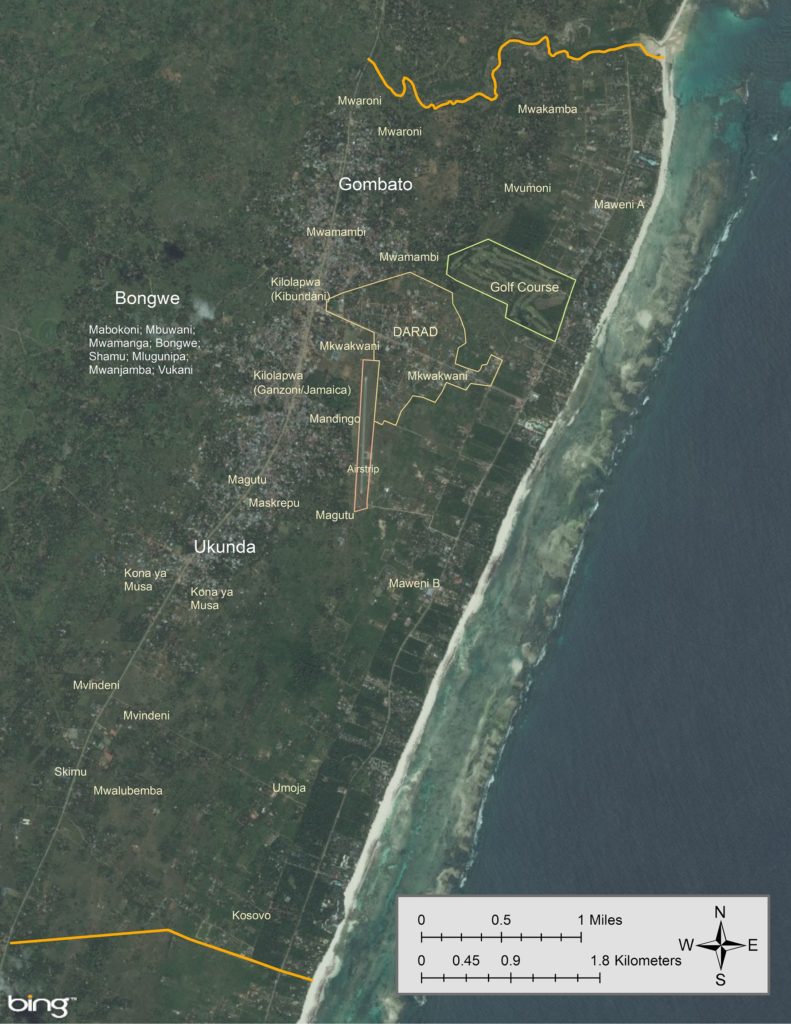

Diani stretches from north to south for about six and a half miles along the beach from the Kongo River to Galu Beach, inland about one and a half to two miles from the beach west to the Mombasa-Lunga Lunga Road (A14, also referred to as Ukunda-Ramisi Road), and then for another three miles inland west of that road (Fig. 1). The center of the area, known as the town of Ukunda, is densely populated. The indigenous people of the area are Digo, one of the nine ethnic communities known as the Mijikenda.[2] Today the area includes Kenyans of various ethnicities who have migrated to Diani, drawn by the promise of a tourism-related economy. Since the 1960s, when Diani’s original inhabitants merely numbered in the few thousands, the population has swelled to close to 75,000. Diani is a contact zone between Kenya’s various communities and also between Kenyans and a diverse group of expatriates, many of whom have settled in Diani permanently or semipermanently.

Officially, Diani is the name of an administrative unit in Kwale County, which according to the 2009 census measures an area of 81 square kilometers and is subdivided into the areas of Ukunda, Gombato, and Bongwe.[3] The majority of the population lives in Ukunda (38,629) and Gombato (24,024), with a smaller population in Bongwe (10,822).[4] Most areas close to the Mombasa-Lunga Lunga Road and the road from Diani to the beach and along the beach road are very densely populated, with 2,271 (Gombato) and 1,542 (Ukunda) persons per square kilometer. This relatively high population density, however, is a very recent phenomenon, and mainly a result of the expansion of the tourism industry in the area. The tourism infrastructure emerged slowly in the 1970s and 1980s along the beach road. But until the early 1980s the several thousand indigenous Digo villagers were not affected much by the changes occurring around them. Today, villagers’ control over land is restricted to only about twenty percent of the land they once considered their own, and their villages are surrounded from all sides by among other structures: residential housing, including lavish private villas with security fences and walls; commercial buildings, such as restaurants and supermarkets; a hospital; various schools; and an airstrip. A dramatic increase in building activities and population began in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and continues to this day.

What are the main factors that brought about these substantial changes in the Diani area? How did the transformations of the past five decades affect local villagers? A review of the longer history of the Diani area reveals an astounding continuity with regard to the question of landownership. In particular, the trends that have occurred over the past fifty years, from the moment of independence in the early 1960s to the area’s integration into neoliberal capitalism over the past thirty years, amount to an unremitting process of gentrification that had already begun during the colonial period.[5] What has occurred in Diani is not unique to the East African coast or even to Africa; similar processes have been underway, especially in areas close to attractive beaches, across the planet. The last twenty years in particular have witnessed a global rush for beachfront property, facilitated by the movement of capital and people from the global north to the global south. These real estate shifts have had a profound impact on local populations and brought into contact individuals and groups of diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Germans have played a central role in building Diani’s tourism infrastructure and in creating the real estate market, and thus in bringing about substantial shifts in landownership.[6]

German Development of Tourism, Business, and Real Estate

German entrepreneurs appeared on the Kenyan scene in the 1960s and became a crucial force in the creation of the coastal tourism infrastructure. While until that time “the coast was the resort chiefly of upcountry expatriates who would hire beach cottages at low rates,” the new hotels built in the 1960s attracted international visitors (Jackson 62). One of the first hoteliers was Edgar Herrmann, also known as “Herrmann the German,” who has been credited by some with coining the slogan “Sun, Sand, and Sex,” which corresponds to the image of Kenya in German mainstream media to this day. Tourism development in Diani began in the early 1960s, and the German share in hotel ownership and hotel management was significant. Until the end of the late 1980s, Germans owned or managed most of the hotels on the south coast: The ten major hotels of that period were Diani Reef, Leisure Lodge, Leopard Beach Hotel, Trade Winds, Diani Sea Lodge, Two Fishes, Africana, Jadini, Safari Beach, and Baobab Robinson. All of them, with the exception of Leopard Beach and Trade Winds, had German management. Four of these ten hotels were German-owned or partially owned by a German company; Leisure Lodge Hotel, Diani Sea Lodge, and Two Fishes were fully in German hands, and the Baobab Robinson was co-owned. The owners of Diani Sea Lodge added Diani Sea Resort to the roster in the late 1991. Some of the hotels that were built in the 1990s, such as Kaskazi, were also German-owned or -managed at some point.

In 2013, only thirteen of the then twenty major hotels remained in operation, reflecting the overall decline of tourism on the south coast, and six of the seven that were closed were African-Kenyan-owned or owned in partnership with African-Kenyans. Four of the closed hotels were owned by Kenyan politicians, namely James Njenga Karume (Indian Ocean Beach Club) and Kenneth Matiba (Jadini, African Sea Lodge, Safari Beach Hotel). Only one hotel that operated then was owned by an African Kenyan. While African Kenyan ownership of hotels was down, Indian (Kenyan and otherwise) ownership was up, making up 61.5 percent (eight) of the thirteen hotels that were open in 2013. The others were owned by Germans (two), French (one), and a Kenyan European (one). Of those thirteen hotels, four still had German management, namely Diani Sea Resort, Diani Sea Lodge, the Sands at Nomads (Austrian), and Leopard Beach, where the German manager has been one of the most successful in the area for close to four decades and partners as Project Manager and Management Consultant with the hotel’s African Kenyan management. While German hotel ownership and management were and continue to be down, the area features a host of cottages and boutique hotels of which many are German-owned or -managed.

Hotel-based tourism also generated the development of a second area of German economic activity in Diani, especially since the late 1980s. Scores of small and larger businesses in Diani are owned by Germans, among them safari tour companies, nightclubs, restaurants, cafés, massage salons, yoga studios, diving businesses, and shopping malls. Originally these outfits targeted tourists, offering supplemental services that the hotels did not. Today, they also cater to the area’s growing residential community. Many of these businesses flourish only for a short period of time, and individual owners and managers come and go, trying (and often failing) to fulfill their dream of living in one of the most beautiful tourist destinations. Many leave bankrupt and disappointed, unable to adjust to Kenyan business practices and often without the kind of expertise that might have ensured success. The successful business owners are those who pursue one of two strategies: either they adjust to the Kenyan environment and work closely with a Kenyan partner (often a spouse), or they control each and every aspect of their business themselves, ideally as a couple or family. Individuals who pursue the second approach, though economically successful, often show severe signs of burnout after a few years, primarily as a result of an overall lack of knowledge about their environment in combination with their attempt to retain German business practices (including timeliness, planning, and reliability). None of the German entrepreneurs that I interviewed spoke any significant measure of Kiswahili, even after decades of having lived in the country, and lacked cultural and historical knowledge about Kenya, producing a significant sense of constant cultural disorientation. Despite these challenges, several of the most successful businesses in Diani are run by Germans, and some of them have been operating for more than ten years.

The third area of activity is the real estate sector. The 1960s and 1970s saw new residential development in Diani, which was initially driven mostly by British citizens who either left the Kenyan highlands to move to the coast or who came first as tourists and then bought land. A wide variety of individuals from various European countries made Diani their home; investors and heirs were joined by adventurous and criminal types, and often these qualities were combined in various colorful constellations.[7] Real estate development was still slow, but in the early 1980s Diani experienced the first major post-independence land alienation scheme, and I will discuss the case in more detail because it exemplifies patterns of economic and political entanglements that persist to this day.

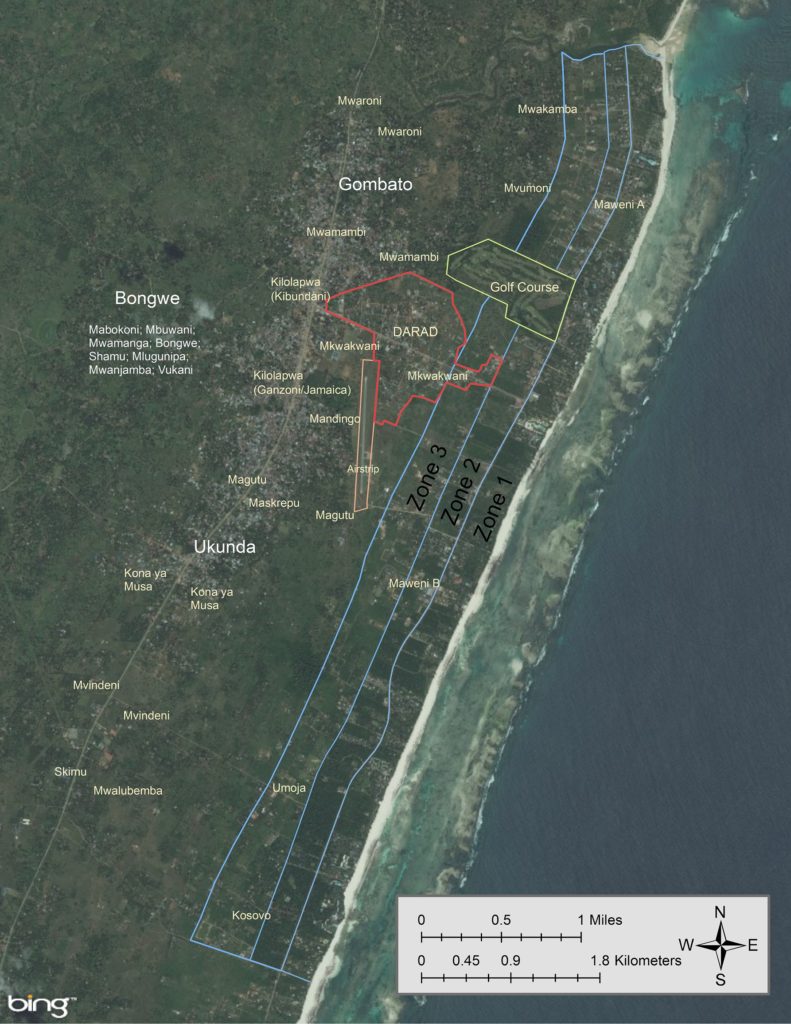

In 1981, Dr. Wilhelm Meister (who owned the majority of shares of Leisure Lodge Hotel), Peter Ludaava (who had been employed at Two Fishes before he came to Leisure Lodge and was Dr. Meister’s “right hand”), and Mr. Shretta (a lawyer from Nairobi who owned about 20 percent of Leisure Lodge shares) founded an organization called “Diani Agriculture and Research Development” (DARAD). The organization bought land to the north and south of the connector road, for various agricultural purposes. When DARAD bought the land, the relevant title deeds were already in the hands of a Kwale District member of parliament, Mr. Juma Boy. Part of the area at stake was known among local Digo villagers as “Chidze,” which means “outside” or “away from the village” in Chidigo. The Chidze land, closest to the area of Mwamambi Village, served as a collective farming area for its inhabitants and those living in the adjacent villages of Mwakamba, Mvumoni, and Mwaroni. Villagers between the connector road and the Kongo River would live on their various agricultural plots in the Chidze area (along with another area called Maweni) during the farming and harvesting season.

The loss of Chidze and adjacent areas was a significant blow to the villagers. Several recounted the events with bitterness. They said that an alliance of local leaders that included the Diani chief, the area MP Juma Boy (the father of Boy Juma Boy, who continues to be an active political figure to this day, and took over from where his father left off also with regard to DARAD), and the area counselor “sweet-talked village elders” into signing a consent, thus permitting the sale. The money from the sale, however, went to the alliance of local political leaders, while the villagers received nothing—and turned to protest. One man recounted how he and his grandfather had been detained at the local police station after a protest against the sale of the land. Another man from Mvumoni remembered a violent fight in 1988 or 1989 outside of Club Willow on the north side of the connector road. These events, people often complained, were not properly covered in the newspapers at the time. During President Moi’s dictatorship, the press was censored, and would stigmatize incidents such as these as the actions of criminals. Villagers were not able to claim reimbursement for their land because they did not own title deeds for the land on which they had lived for centuries (and in most cases, villagers throughout the area still do not own title deeds for their land, even though allotment letters exist). The villagers were mostly illiterate and unable to represent themselves effectively, especially once their own leadership had given in to the demands of the more powerful.[8]

The officially authorized intent of DARAD (in contrast to its actual pursuits) was agricultural development, including a veterinary station. The organization conducted research on growing cloves, spices, and grasses through their Grassversuchsfarm, (experimental grass growing farm), for which DARAD is said to have received a loan from either the German Development Agency (Deutscher Entwicklungsdienst, DED) or the Society for Technical Collaboration (Gesellschaft für technische Zusammenarbeit, GTZ).[9] DARAD also featured a large carpentry training program, Diani Furniture, that was run by a German carpenter, Mr. Krüger (a “Schreinerei mit Meister, ein Herr Krüger”). The carpentry shop there was evidently funded by CIM, the German Center for International Migration and Development (Centrum für Internationale Migration und Entwicklung).[10] Some employees at Leisure Lodge are also said to have been paid with CIM money. While DED and GTZ were officially not supposed to work with private enterprises, CIM often collaborated with private companies, and, was evidently scandal-ridden at the time. DARAD also managed to secure two airplanes from the German development agencies that were supposed to be used as medical transport by the Flying Doctors Society of Africa. Dr. Meister, with his training as a lawyer, is said to have been savvy in organizing these monies. His supporting cast included the local member of parliament (MP), the Diani Chief, and other local stakeholders and government officials.

Over time, the truth about DARAD came to the surface. The Grassversuchsfarm turned out to be a development project for a planned golf course, construction of which began (with government permission) in 1991 and which opened after various delays in 1997. The rescue planes were used for safari tourism. And the carpentry training program was in fact a successful privately-owned furniture store, Diani Furniture, which made furniture for various hotels, among other enterprises. When the misuse of German development funds was uncovered, the scandal broke, though apparently with no consequences for the Kenya-based players.[11] Dr. Meister was also involved in what became known as the “Amigo-Affair” in Germany. The Bavarian minister president, Max Streibl, who was forced to resign over a scandal involving favoritism of the kind described here had been a frequent guest at Leisure Lodge Hotel.

The DARAD-scandal and the Amigo-Affair were not the only time that German development and other governmental agencies made headlines because of their activities in Kenya. In 1998, one of the German project managers who oversaw forestry development projects was murdered in the area (Rodgers and Burgess 328). Most likely, none of the funds provided by the German government for these instances of corporate development in Kenya were ever returned. Struggle over the area continued, and even though DARAD was dissolved in the 1990s, the question of ownership of DARAD land is contentious to this day.

But, clearly, the manipulated sale of the Chidze land in the 1980s was only the first in a series of changes of landownership that led to business and real estate development in Diani. An outright building boom began in the early 1990s. Whereas upscale housing development was previously restricted to beachfront property, enclaves of luxury villas sprung up throughout the Diani area. The entire area has been surveyed and is recorded on registration map sheets that indicate the divisions into numbered rectangular plots, many of which are subdivided into smaller units. The various sections of the area are conceptually tied to the beach, which clearly indicates that beachfront property is valued the most: The first section is referred to as “Beachfront” property; after the immediate “Beachfront” section, the next section stretches to the beach road, and is known as “Row 1.” Afterwards, every 300 to 350 meters, another section is theoretically marked by another “road,” but these roads, if they are identifiable, are not paved and often do not even cut across the entire area. As of the time of the completion of my research, most of the development occurred in Rows 2, 3, and 4. I divide the areas into “zones” based on the phase of development; “Zone 1” combines the beachfront itself and Row 1, as this was the first area of development, through the period up until the 1970s. Development in Row 2, here “Zone 2,” began in the 1980s. Building activity in Row 3 and 4, which constitute “Zone 3,” started in the second half of the 1990s. Construction in the DARAD area also began in the 1990s (Fig. 2). Building activity continues in all zones to this day. As a result, villagers are squeezed into a constantly decreasing area from all sides, and their modest villages are surrounded by modest to upscale modern housing.

What drove the real estate push that began in earnest in the 1990s? Particularly consequential were the Structural Adjustment Policies imposed on Kenya by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund in the early 1990s (Swamy 193-237; World Bank). Kenya’s implementation of privatization and other neoliberal practices were promptly rewarded with an IMF loan (“IMF Approves”). The fact that these policies failed is by now widely accepted (Moyo 19-22; Stein; Rono; Kang’ara; Thomas-Emeagwali; Avery; Sparr; Thurow and Kilman). As elsewhere in the global south, and also some regions of the global north, poor people got poorer, while the rich got richer: “In Kenya, people living below the poverty line increased from 46 percent in 1992 to 49 percent in 1997, and [increased] further to 56 percent in 2000” (Wanjiru 17). In Diani, these policies made it much easier for foreigners to invest and to buy land, resulting in substantial changes in landownership and the development of foreign-owned businesses in the area.

German realtors were crucial in facilitating a consequential shift in landownership from villagers to settlers. Joe Brunlehner, who has received significant attention for his often contentious activities and who widely advertises “Diani Homes—Seit 1983 Garant für Ihre Immobilien in Kenia” (Diani Homes—Guarantor for your real estate in Kenya since 1983), continues to be one of the key agents (Diani Homes: Kenia Immobilien; Diani Homes, “Über Uns”). Other German developers are less visible but have also acquired and resold a large number of plots. I interviewed Mr. Neugebauer, an associate of Joe Brunlehner, in July 1999. He confirmed that the building boom began when the legal situation changed in 1992 and “foreigners were allowed to buy property” without the previously existing condition that a Kenyan must partner with the foreigner for a ninety-nine-year lease. As of July 1999, the company had sold about 260 houses to around two hundred families in Diani and the adjacent Galu areas; some families, Neugebauer said, had bought two and even three houses. Ninety-five percent of the sales went to Germans, with 60 percent of those coming from the eastern part of the country, the area of the former GDR. Neugebauer said that most of these had been high-ranking officials (“früher hohe Tiere”) or younger individuals who had made money in the first few years after German unification. Rumor in Diani has it that many of these influential figures from East Germany had worked for the Stasi, the Ministry for State Security (Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, MfS). Most of the plots were located in Row 2 and 3, with prices for homes listed in 1999 ranging upwards from 165,000 German Marks. Neugebauer also mentioned that the IMF and the World Bank regulations had been crucial in this regard; credits to Kenya, he said, had been tied to stipulations that made it possible for foreigners to acquire property in Kenya. Neugebauer was clearly fully aware that the company’s success was intricately linked to IMF and World Bank policies.

Brunlehner (who supposedly had to leave Germany because of tax evasion charges) is known in Kenya and Germany as “Mombasa Joe,” which conveys a sense of the aura he has acquired (“Prügelprozess gegen Prinz Ernst August”). Brunlehner and some of his associates are representative of a group of controversial German entrepreneurs who are operating in Kenya.[12] The Italian community on the coast has much to show in this regard as well (Gitau; Dabbs). Beyond Germans and Italians, the Kenyan coast has been described more generally as an area “where people go to escape their pasts . . . [they] have all come to Diani to avoid alimony payments, charges of tax evasion, and disgruntled clients back home” (Wadhams).

Though the German real estate boom in Diani peaked in the late 1990s, new private homes have been built continuously, and today, real estate is hot again. With this recent development push, we can identify a new phase of gentrification in Diani. Its designation as a resort town in the country’s vision plan (Kenyan Vision 2030) as well as the prospect of a bypass that would circumvent the Likoni ferry have brought speculators to the area.[13] But all over the world, there is a similar rush under way for beachfront and near-beachfront property. While many real estate transactions occur through consulting firms and international real estate companies (such as Knight Frank), the only company that is registered locally in Diani as a real estate company is run by a German couple. Baobab Holidays Homes (Kenya) Ltd. has been active since 2010, evidently very successfully, and clearly in competition with Diani Homes and other consulting firms (Baobab Homes). In an interview in November 2013, the owners, Sandra Nikolay and Frank Meininghaus stated that demand was high. In November 2013, Baobab Holiday Homes had an impressive 170 listings on the market, including homes, apartments, and plots. The properties are mostly located in Diani and Galu Beach, as well as in several other locations on the south coast and in Kwale. The company was recording about two hundred visitors per day to its website. Eighty-five percent of their customers came from Nairobi, among them UN officials, INGO workers, and businessmen and women from various European countries. The owners also noted that African Kenyans increasingly made use of their services, a trend they only expect to continue based on the anticipation of upcountry-driven gentrification.[14] Nikolay and Meininghaus also stated that they did not deal with land that was owned by indigenous villagers because the legal situation was often too obscure. The law mandates that all family members have to agree to a sale, and in their view, tracking down each and every member of an extended family proves to be too difficult. They decided to stay away from these potentially conflict-laden situations. Overall, Germans continue to represent a driving force, both as realtors and buyers in the real estate market.[15]

The developments in Diani, especially as they occurred in the 1980s and 1990s when German entrepreneurs dominated the area, took place in the context of a general land-grabbing frenzy. As Paul Ndungu explained, “Our conservative estimate was that some 200,000 illegal titles were created between 1962 and 2002. Close to ninety-eight percent of these were issued between 1986 and 2002” (Ndungu 5). Clearly, this overall lawlessness created a climate that facilitated illegal transactions of land in Diani as well. This fact does not absolve German developers from their responsibility to know whether the transactions they were involved in were legal or not; surely many of them were aware of areas of illegality. But even when transactions occur in a legally sound manner, as indicated by recent developments, the ultimate effect on the local community remains the same: the resources of the original villagers are diminished (as stated before, Digo in Diani control only about twenty percent of the land they once owned or used) and the local Digo community, as well as its specific history and culture, is imperiled.

Effects of North-to-South Transactions

For a colonized people the most essential value,

because the most concrete, is first and foremost the land:

the land which will bring them bread and, above all, dignity.—Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

As Frantz Fanon and also Fred Pearce (in his study of the global extent of land-grabbing) acknowledge, landownership is central to questions of identity and dignity (Pearce 61-62). In Diani, Digo language, culture, and history is tied to land, and as ownership of ancestral land is diminished, so too is the cultural life of the Digo in this area. While Digo who live in many areas throughout Kwale County and into Tanzania are not challenged as a people by what is happening in Diani, a part of the larger Digo culture that is tied to, among other sites, the historical kayas (homesteads) in the Diani area as well as the Kongo Mosque, is threatened to disappear.

In the absence of large-scale approaches to preserve Digo land and culture in Diani, the business activities that I have outlined here are bound to continue. Of all the economic activities discussed here, the hotel industry has arguably had the most beneficial effect on the area (through job creation) and did not affect landownership immediately. However, the side effects of tourism, especially the emergence of the globalized real estate market, certainly did. Yet Digo agency will not be preserved by way of a certain percentage of Digo privately owning land in the area. While some villages, such as those in the northern part of Diani, continue to display a significant degree of cohesion, increasing private landownership will only divide the community further. Ultimately, all communities and cultures change, and privatization, new concepts of the family and labor, and the overall scope and pace of change in the area will create social energies that may also result in new communal practices. In the meantime, the community’s overall sense of loss and the multiple grievances are articulated via a discourse that emphasizes the perils associated with the loss of land; this discourse, however, addresses more than just landownership, as Digo landownership is related to an entire way of life.

Acknowledging the role of Germans in developments such as those outlined in this essay requires us to pay attention to dimensions of neoliberal capitalism that structure transnational relations in our contemporary world. Over the past fifty years, economic actions of German entrepreneurs and individual investors have affected the economic and social landscape of Diani in fundamental ways: in particular, the distribution of landownership and the business infrastructure of this Kenyan location have been shaped by the activities of Germans, Swiss, and Austrians (among others). These activities are part of a larger north-to-south trend that has yet to be studied systematically; it is a trend that builds substantially on the inequalities created during the colonial period. Future research on the ways in which German capital and social energies are shaping material realities in many locations of the world and have a tremendous impact on infrastructure and social relations in those areas will deepen our understanding of these transnational dynamics.

Works Cited

Avery, Natalie. “Stealing from the State (Mexico, Hungary & Kenya).” 50 Years is Enough: The Case Against the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Ed. Kevin Danaher, 95-101. Boston: South End Press, 1994. Print.

Berman, Nina. Germans on the Kenyan Coast: Land, Charity, and Romance. Forthcoming. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2017. Print.

————. “Neils Larssen: A Life Afloat.” South Coast Resident’s Association Newsletter, 37 (Aug. 2011): 4-5. Print.

————. “Neils Larssen: A Life Afloat.” South Coast Resident’s Association Newsletter 38 (Sep. 2011): 3-4. Print.

Baobab Homes & Holidays Kenya. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Dabbs, Brian. “Kenyans See the Italian Mafia’s Hand in Worsening Drug Trade.” The Atlantic 30 July 2012. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Diani Homes: Kenia Immobilien. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Diani Homes. “Über uns.” Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Fanon, Frantz. Wretched of the Earth. Trans. Richard Philcox. New York: Grove, 2004. Print.

Gerlach, Luther Paul. The Social Organization of the Digo of Kenya. Diss. U of London, 1960. Print.

Gillette, Cynthia. A Test of the Concept of Backwardness: A Case Study of Digo Society in Kenya. Diss. Cornell U, 1978. Print.

Gitau, Paul. “How Italian Mafia Gained Control of Malindi.” Standard Digital, July 3, 2012. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

International Monetary Fund. “IMF Approves Three-Year Loan for Kenya Under the ESAF.” Last updated April 26, 1996. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Jackson, R. T. “Problems of Tourist Industry Development on the Kenyan Coast.” Geography 58.1 (1973): 62-65. Print.

Kang’ara, Sylvia Wairimu. “When the Pendulum Swings Too Far: Structural Adjustment Programs in Kenya.” Third World Legal Studies 15.1 (1999): 109-51. Print.

KenyaVision2030. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Krapf, Johann Ludwig. Reisen in Ostafrika, ausgeführt in den Jahren 1837-1855. 2 vols. Stuttgart: Brockhaus, 1964. Print.

LTI Hotels. “Company Details.” Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Mondinion. “Kenya Realtors & Real Estate Agents.” Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Moyo, Dambisa. Dead Aid: Why Aid is not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009. Print.

Ndungu, Paul. “Tackling Land Related Corruption in Kenya.” Unpublished manuscript, last modified November 2006. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Pearce, Fred. The Land Grabbers: The New Fight Over Who Owns the Earth. Boston: Beacon P, 2012. Print.

“Prügelprozess gegen Prinz Ernst August: ‘Der Joe hat uns verarscht.’” Spiegel Online 7 July 2009. Web. 9 Feb. 2016.

Rodgers, W. A., and Neil D. Burgess. “Taking Conservation Action.” Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa. Eds. Neil D. Burgess and G. Philip Clarke. Cambridge: IUCN, 2000. 317-34. Print.

Rono, Joseph Kipkemboi. “The Impact of the Structural Adjustment Programmes on Kenyan Society.” Journal of Social Development in Africa 17.1 (2002): 81-98. Print.

Sparr, Pamela. Mortgaging Women’s Lives: Feminist Critiques of Structural Adjustment. London: Zed Books, 1994. Print.

Stein, Howard. Beyond the World Bank Agenda: An Institutional Approach to Development. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2008. Print.

Steinkühler, Karl-Heinz. “Verbrechen im Mafia-Paradies.” Focus Magazin Online 8 Oct. 1995. Web. 9 Feb.2016.

Swamy, Gurushri. “Kenya: Patchy, Intermittent Commitment.” Adjustment in Africa: Lessons from Country Case Studies. Eds. Ishrat Husain and Rashid Faruqee. Brookfield: Ashgate, 1996. 193-237. Print.

Thomas-Emeagwali, Gloria, ed. Women Pay the Price: Structural Adjustment in Africa and the Caribbean. Trenton: Africa World Press, 1995. Print.

Thurow, Roger, and Scott Kilman. Enough: Why the World’s Poorest Starve in an Age of Plenty. New York: PublicAffairs, 2009. Print.

Wadhams, Nick. “Fleeing Justice, All the Way to Africa.” The Globe and Mail 17 Mar. 2007. M2. Print.

Wanjiru, Rose. IMF Policies and Their Impact on Education, Health and Women’s Rights in Kenya. Nairobi: ActionAid International Kenya, 2009. Print.

World Bank. Kenya: Re-Investing in Stabilization and Growth through Public Sector Adjustment. Washington, DC: World Bank, 1992. Print.

[1] My forthcoming study, Germans on the Kenyan Coast: Land, Charity, and Romance discusses these dimensions in more detail.

[2] Scholarship on the Digo is scant. Some of the earliest known references to discussions in European languages date back to the mid-nineteenth century (e.g. Krapf). Several anthropological studies were conducted between the 1950s and 1970s (Gillette; Gerlach). Apart from several article-length analyses of various subjects, no comprehensive study exists that focuses on the Digo of the Diani area.

[3] The three areas form two wards, namely Gombato/Bongwe and Ukunda, which each have one representative in the Kwale County Assembly.

[4] Figures according to the 2009 census. The dataset and information about the individual villages was provided by the Chief’s office in Ukunda.

[5] For a review of developments under colonialism and a discussion of gentrification, see the discussion in Chapter I of my forthcoming study Germans on the Kenyan Coast.

[6] Research for this study was conducted during five research stays between 2009 and 2014. I collected oral history accounts from a wide range of individuals living in Diani as well as a variety supporting sources that provided me with detail regarding the economic, social, and demographic changes occurring during this period.

[7] For a portrait of a Swedish man who led an adventurous life in Kenya and beyond, see my essays on “Neils Larssen.”

[8] Because lawsuits were pending it was difficult to find villagers who were willing to volunteer information. Information about the history of DARAD was gathered in interviews with various Diani residents, including villagers, hotel managers, and Mr. Klaus Thüsing, who was the country director for the German Development Agency (DED) in Kenya from 1988 to 1993.

[9] Under these names until 2010, now both part of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, GIZ (Society for International Collaboration).

[10] Centre for International Migration and Development. CIM is today folded into the GIZ (Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, Organization for International Collaboration) which is the result of a merger between the DED and GTZ. I contacted GIZ and CIM to corroborate data gathered during interviews, but, after an initial exchange, received no further responses once representatives realized what kind of information I was interested in. The response was that they had no access to information involving the previous organizations (“Wir führen kein Archiv zu der Arbeit der Vorgängerorganisationen der GIZ”; “Leider liegen uns keine Informationen oder Dokumente zu dem von Ihnen geschilderten Fall vor”). Email communication, February 2015.

[11] Krüger’s collaboration with Dr. Meister ended around that time as well, presumably because he had not been paid properly, and he left with some of his machines overnight, exacerbating the scandal.

[12] See the case of Andreas Költz in Steinkühler. Both Brunlehner and Pullig (his name x-ed out in this article) play a role in this story as well.

[13] The ferry at Likoni is the only means of connection between Mombasa and the south coast. Tourists traveling to and from the airport as well as commercial traffic from the north and inland have to cross via the ferries, with waiting times often reaching several hours.

[14] In late 2013, the company’s platform was voted the #1 realtor in Kenya by one of the largest international real estate platforms, Mondinion. Worldwide they were listed as # 9 among 8,933 real estate companies. See “Kenya Realtors & Real Estate Agents.”

[15] For additional quantifiable data on the impact of German activities in Diani, see Berman, Germans on the Kenyan Coast.