Ernst Lubitsch & the Transnational Twenties: The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (USA 1927)

TRANSIT vol. 10, no. 2

Rick McCormick

Abstract

Ernst Lubitsch epitomized the transnationalism of the cinema in the 1920s as the first German director to come to Hollywood and one who brought over a number of German film artists to Hollywood over the course of the decade. In America he followed developments in German cinema in terms of technical innovations and popular genres, and he published in the German film press. The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg was meant to compete with similar silent operetta films being made in Germany, and making the film, Lubitsch had the chance to return to Germany for the first time since 1922. The film was transnational not only because of its connection to the movements of artists, technicians, ideas, styles, and genres back and forth across the Atlantic, but also for the ethnic, gender, and sexual politics of the film and its production itself: e.g., the “migration background” not just of Lubitsch but also of the film’s male star, Ramón Novarro.

The silent cinema was already transnational to a degree that would be difficult to maintain once film industries began to convert to sound cinema, and Ernst Lubitsch epitomized the transnationalism of the 1920s. His last two films in Germany were financed with American money; arriving in Hollywood at the end of 1922, he brought other German artists and technicians with him and sent for more over the course of the decade. Lubitsch used European—mostly Central European—plays and operettas as the basis of his American films, and he followed the German cinema closely in the 1920s, imitating technical innovations and popular genres, meanwhile publishing articles in the trade journals in Germany. In 1927 he made his first silent operetta film, which was also his first American film set in Germany: The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg, a film meant to compete with similar films being made in Germany.

In discussing this film, I will demonstrate that it is not only transnational in terms of the movements mentioned above of artists, technicians, ideas, styles, and genres back and forth across the Atlantic, but also because of the ethnic, gender, and sexual politics of the film and its production itself. The politics of the film were determined in many ways by the position of Lubitsch himself as a German Jew whose career was shaped by his father’s migration from Russia to Berlin and his own migration from Berlin to Hollywood. The migration from Mexico of the film’s star, Ramón Novarro, and other aspects of how he was positioned in American society are also relevant to my analysis.

Lubitsch in the 1920s

Much has been written about the second wave of German émigrés to Hollywood who came after 1933 as refugees. But also important and deserving of attention is the story of the first wave that came in the 1920s, when there were movements across the Atlantic in both directions. In that decade, there were many transnational co-productions involving the German cinema and the American cinema, and it all began with Ernst Lubitsch. The great commercial success in the US of his film Madame Dubarry (1919), which premiered in New York as Passion in December 1920, opened the U.S. market to German films again after World War I. Hollywood’s interest in Lubitsch specifically led to the formation in Berlin of the Europäische Film-Aktiengesellschaft (EFA) in 1921, which was financed by Famous Players Lasky/Paramount. Lubitsch and his producer Paul Davidson quit UFA to join EFA; thus Lubitsch’s last two German films, Das Weib des Pharao (Loves of the Pharaoh, 1922) and Die Flamme (Montmartre, 1923) were actually financed by American money and benefited from American technical expertise and equipment (Drössler and Thompson, Herr Lubitsch).

But the EFA model of an American-financed production company in Europe failed; it was easier to invite Lubitsch to Hollywood, and in December 1922 he arrived there. He was the first of many German film artists to go to Hollywood in the 1920s. Among those who came after Lubitsch were Friedrich Murnau, Karl Freund, Erich Pommer, Emil Jannings, Conrad Veidt, Wilhelm Dieterle, and Marlene Dietrich. Many film émigrés of the 1920s had close connections to Lubitsch, including the star of many of his German films, Pola Negri, as well as the screenwriter Hanns Kräly, the film editor Heinz (in Hollywood: Henry) Blanke, and the designer Hans Dreier. Blanke came on the ship with Lubitsch to America, and Lubitsch soon sent for Kräly, then for Dreier, and later for costume designer Ali Hubert to join him in Hollywood.

Lubitsch came to Hollywood at the end of 1922 because Mary Pickford had hired him to direct her in a film at United Artists. With Pickford he made Rosita, which was released on September 3, 1923. At first the German film industry expected Lubitsch to return to Germany after one film. Whether he would return or not was a topic of concern already in April of 1923 (“Kommt Lubitsch nicht zurück?”). Once it was clear that he was staying longer, the film press continued to report rumors that that he would return to make films in Germany, practically up until 1933 (e.g., “Ernst Lubitsch wird in Berlin drehen?”). Lubitsch did consider returning to Germany after Rosita, but then he was offered a very generous contract to make six films for Warner Brothers at $60,000 per film, which also granted him autonomy that was very unusual for directors in Hollywood.

At Warner Lubitsch did not return to historical epics like Madame Dubarry; instead he developed what would be called the “sophisticated comedy,” a form very different not only from his costume epics but also from his German comedies, which had been broad and anarchic. The “sophisticated comedy” would be much more like a chamber play. He adapted a German play from 1909 to make The Marriage Circle. A critical and commercial success, it was a stylish comedy about adultery but set safely in Europe. His sophisticated comedies would usually be set in an imaginary Vienna or Paris.

Lubitsch continued to use European plays and operettas as the basis of his American films, and he followed the German cinema closely, imitating technical innovations pioneered by Murnau, E.A. Dupont, and Karl Freund. His last film at Warner, So This is Paris (1926), clearly tries to imitate these innovations, as well as other mid-1920s German developments in cinematography and montage, in its “Charleston” sequence. At this point in the mid-1920s, critics and the film industry wondered if he would ever make another blockbuster historical epic like Madame Dubarry (e.g., Tully).

After leaving Warner Brothers, Lubitsch made a silent operetta film for MGM based on a German play; it became The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (1927), which I will be examining in more detail here. This project gave him the chance to visit Germany for the first time since he had come to America; while there he was celebrated by the German film industry. After The Student Prince, Lubitsch moved to Paramount, where he finally succumbed to the pressure to make another big historical epic: he made a film about the mad Russian czar, Paul I. The Patriot (1928) starred Emil Jannings, who wrote in his memoirs that The Patriot was his best American film (Eyman 144). Next came his last silent film, Eternal Love (1929), an example of another German genre, the Bergfilm, a mountain film starring John Barrymore and, newly arrived from Germany, Camilla Horn.

In the early sound era, Lubitsch made musicals using the operetta model, beginning with The Love Parade in 1929. In an interview in late 1929 with a reporter from the German trade journal, the Film-Kurier, he insisted that musical films should not be naturalistic, with the singing justified by a plot about performers who sang onstage or in night clubs. This would be the main American model for the musical, at least until Rodgers and Hammerstein in the 1940s. Lubitsch said that instead of any attempt at realism, the musical should be based on fantasy, as was the case with the operetta. In the latter form, the characters used songs instead of speeches to express their emotions (“Gespräch mit Ernst Lubitsch”). The songs were not an interruption of the story but rather integral to it (in contrast to “real life”).

When Lubitsch returned to Germany for the last time in November 1932, the film industry celebrated him once again. But soon thereafter, in January 1933, all that would change as the industry accommodated the new regime: by March firing all the Jews in the industry. 1933 was a much bigger disincentive to the transnationalism of the 1920s than the onset of the sound cinema had been. 1933 also led to the second—and much larger—transnational wave of émigrés from Germany to Hollywood, most of them Jewish refugees. Lubitsch, along with Paul Kohner, Salka Viertel, and others, would help to find them work in Hollywood.

The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg

This operetta film premiered on September 21, 1927. Making such a film set in Heidelberg at the turn of the century was clearly influenced by film operettas and Heidelberg romances being made in Germany in the mid-1920s (Kracauer 140-1; Rogowski 3, 7), as well as by Erich von Stroheim’s success with The Merry Widow for MGM in 1925.

The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg is based on two sources: the 1901 German play Alt-Heidelberg by Wilhelm Meyer-Förster and the 1924 American operetta The Student Prince, which was based on the same play and combined with music composed by Sigmund Romberg, an Austro-Hungarian Jew who had come to America in 1909. This was the first time Lubitsch used an operetta to make an operetta film, as opposed to using one as the basis for a sophisticated comedy. What was a silent operetta film? It was based on an operetta and was released with a musical score to accompany the film—as most silent films were, but in this case the music was often the same or similar music to what had been composed for the stage operetta. With regard to The Student Prince, the American critic Underhill wrote that Somberg’s music for the operetta was adapted well for the score of the film by David Mendoza and William Axt. In the German press, critics wrote that the music for the German premiere had been composed by Schmidt-Gentner. This may also have been an adaptation of Somberg’s music; in any case, two German critics, Kurtz and Jäger, write that the score was impressive.

This was Lubitsch’s only silent operetta film, but as indicated above, this would be the model he would adopt for the first sound films he would make, which were musicals. Hollywood wanted him to make more blockbuster epics like Madame Dubarry and The Patriot, but he continued to opt for operettas and sophisticated sex comedies.

The actual screenplay for The Student Prince was written by Hanns Kräly, who had been working with Lubitsch since 1915. Lubitsch hired Ali Hubert from Germany, who had been his costume designer on some of his German films. Hubert brought costumes for The Student Prince from Germany to Hollywood; he would continue his career there (Hake 38; “Drei Atelier-Tage”). During the making of The Student Prince Lubitsch visited Germany, supposedly in order to shoot location footage of Heidelberg while there, but none appears in the final film, which recreates Heidelberg on an outdoor set in Laurel Canyon. Lubitsch’s explanation for why none of the footage shot in Heidelberg was used appears in a New York Times article from September 1927, “Lauds Producing Here.” He claimed that the footage shot in Heidelberg proved how accurate the research behind the sets constructed in Hollywood had been. He also stated that, “Had we used actual streets [in Heidelberg] we would have faced lighting problems….”

While in Germany, Lubitsch visited family and friends, and as I have indicated, he was celebrated by the German film industry. He was called a “Pionier des Deutschtums in Amerika,” a pioneer of Germanness in America (“Streit um ‘Alt-Heidelberg’”).

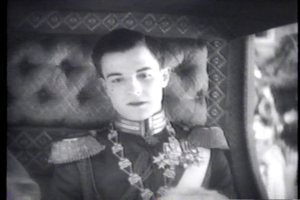

The Student Prince stars Ramón Novarro, the Mexican actor who had succeeded Rudolph Valentino as America’s favorite Latin lover; he plays Karl Heinrich, the young prince of Karlsburg, a tiny Central European, German-speaking principality at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century. Oppressed by his princely role since childhood, he goes to Heidelberg with his beloved tutor to study there, and it is there that he can live as a normal young man, joining a Burschenschaft (a German student fraternity) and falling in love with the young woman, Kathi, who works in the beer garden of her uncle’s guest house. She is played by Norma Shearer, cast supposedly at the whim of her fiancé, Irving Thalberg, the powerful production head at MGM. Of course their love is doomed, because Karl Heinrich’s uncle, the king, falls ill, and the prince must return to his small country, where he soon becomes king and then is forced into an arranged marriage with a princess. Kathi too will marry a man she doesn’t love. Thus the film is a romance, but not a romantic comedy, as it ends in a melancholy way for both lovers. There is a wedding at the end of the film, but it is of Karl Heinrich and a princess he doesn’t love (and whom we never see).

According to Weinberg (103-04), The Student Prince was both a critical success and a hit (but cf. Eyman 135). German and American critics praised the film for the most part. The Wilhelminian, feudal-aristocratic backdrop of the film was clearly antiquated, according to German critic Rudolph Kurtz, but he credited Lubitsch with making a fresh and poignant film devoid of cloying sentimentality. Slavoj Žižek has recently suggested that Lubitsch is the “poet of cynical reason,” but I would disagree. He is often ironical, but he is not cynical, and especially not in this film. The film is poignant because it is about an impossible love, one that cannot be because of oppressive social barriers. For all his power, Karl Heinrich is portrayed here as a small young man with dark eyes and hair who cannot marry the woman he loves (who has lighter hair and a lighter complexion). Ethnic, gender, and sexual politics are at play here.

In 1927, German critics Jäger and Kurtz found Norma Shearer’s Kathi too “American,” and some American critics found her too old or too sophisticated (Underhill; Huff 17). Writing much more recently, Kristin Thompson gets at the issue more forthrightly: she writes that when Shearer first meets the prince, her gaze is not naïve but rather “conveys something like fascinated lust” (“Lubitsch” 403). Thompson implies that this was not what Lubitsch wanted, but I would argue that this is precisely what one should expect in a Lubitsch film. For when one examines the scene in which Karl Heinrich and Kathi meet for the first time, one notes that, yes, Kathi’s gaze is perhaps a bit lustful: she moves (quite boldly) around him twice, looking him over (Figs. 1 & 2). But given what we know of Lubitsch’s directing style, in which he typically acted out what he wanted each actor (male or female) to do, it is hard to imagine that he did not want Shearer to perform as she does in this shot.[1] Above all Kathi’s gaze is powerful, even though she is clearly the prince’s social inferior: as happens so often in Lubitsch films, it is the woman who initiates the seduction (Weinberg 60-61).[2] Perhaps this is what the German critics found too “American,” and the American critics too “sophisticated.”

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Ramón Novarro was faulted by some American critics for being “a little too Latin” for the role (Hall; Huff 17). What to make of this dark-haired, dark-eyed young man who cannot overcome the social barriers that make it impossible for him to marry the woman he loves? I would suggest a “transnational” reading here, specifically a German-Jewish reading. As I have mentioned, Lubitsch’s career was shaped in important ways by transnational migration: his father’s migration from Russia to Berlin and his own migration from Berlin to Hollywood. Ofer Ashkenazi argues that in the work of German-Jewish artists before 1933, one often finds “double-encoding” (26-29), such that a covertly German-Jewish perspective functions to make an overt, general critique of oppressive social restrictions on behalf of a cosmopolitan, liberal order that would be tolerant of difference (especially, in the covert subtext, Jewish difference).

What might that mean for this film? In it we find an aging, authoritarian, hierarchical order that is in tension with a youthful, egalitarian sensibility associated with emotional warmth and the bonds of love. The older order is gendered very much as masculine and embodied in the cold father-figure, Karl Heinrich’s uncle, the king; the newer sensibility is gendered as more feminine. As a child, Karl Heinrich clings to the woman who is his nanny, fearing the coldness and militarism of his uncle’s kingdom. Arriving in Karlsburg, he runs away at the sound of celebratory cannon fire—away from the king and back into the arms of his nanny. Later, the king sends away the nanny, and Karl Heinrich cries. The king then admonishes him sternly: “A prince never cries.” The boy obediently wipes his tears from his eyes, and then, before shaking his uncle’s hand, he wipes his hand on the back of his pants, which we view in an irreverent close-up of the boy’s behind. This carnivalesque “touch” makes the film’s sympathies clear: for tears, laughter, and the body, and against an authoritarian order that strives to discipline and “armor” the body (Figs 3-5).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

The nanny is replaced by the masculine but rumpled, warm, affectionate, and lenient tutor, Dr. Juttner; next there is Kathi, the bold, impetuous, passionate barmaid with whom the prince falls in love. Finally there is the youthful, exuberant, affectionate Karl Heinrich himself, who will be disciplined over the course of the film into losing his sweet smile, ending up in cold, repressed melancholy by the end. Within that realm of the film represented by its youthful, egalitarian, affectionate, and more feminine characters, oppressive social barriers of class can be overturned by the power of human affection. In that realm masculinity is represented in a decidedly less rigid and militaristic way, and instead in a softer, more emotional way by Juttner and the prince. This softer masculinity could be read as Jewish; Joel Rosenberg has written that Juttner is one of the implicitly Jewish characters in Lubitsch’s films. I would add that the dark-haired Mexican actor, Novarro, was probably most famous in America at the time for his portrayal of a Jew in Ben-Hur (1925), in which he played the title character. In any case, it is the older, colder, hierarchical, more masculine—and more “German”—order that prevails in the film.

The “Lubitsch touch” is always elliptical and metaphorical. As Aaron Schuster defines Lubitsch’s “basic principle”: “Never say anything directly when a good metaphor will do” (19). We can expect no overt political statement about Jews or gender or politics. Lubitsch is never a realist, and this film is certainly no “realistic” portrayal of Heidelberg or of the archaic political order we find in Karlsburg. It is about a love that cannot be because of oppressive social barriers. It is also about a man who because of his social position is disempowered, castrated even. Much as he tries to find a way to marry the person he loves, he is overpowered by larger social forces. We are used to seeing aristocratic women in such a position: as Lil Dagover states as Jane in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, “We queens cannot follow the dictates of our hearts.” It is less common to focus on a man trapped in such a position.

Most critics liked Novarro’s performance, but again, there were some reservations were raised about his being “too Latin.” Was he perhaps too dark for the part? It was reported that make-up was applied to make him look lighter, but that it made him look somehow more artificial, too much like an actor (Variety). Perhaps it also made him look too effeminate? Schallert wrote that he preferred Novarro in “less sentimental roles.” I would argue that Ramón Novarro’s performance is poignant as a youthful, affectionate, less than fully masculine prince who becomes very cold and melancholy after being denied the love of his life (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6

Part of what might be poignant here has to do, perhaps, with Novarro’s own situation as a closeted gay actor. Of course all gay actors were closeted at this time, but the closet had to be locked even more tightly if you were marketed as a “Latin lover” and adored by straight American women. Novarro knew a lot about “impossible love.”[3]

During the mid-1920s, Lubitsch was attacked for making “frothy films” for female audiences (“sophisticated chambermaids”), as opposed to serious, historical epics (Tully). While he was making the film, Lubitsch was asked how he could do anything original making a film in the rather clichéd genre of the Heidelberg film. He replied, “Well, for one thing, there won’t be any duels in it” (Weinberg 102). And in fact, in his film the young men of the Burschenschaft do not fence; they dance, they toast Kathi, and they drink lots of beer. Only later, after Karl Heinrich becomes king, do they behave in a cold, authoritarian, and regimented way, each of them bowing like a robot to their former comrade, as Karl Heinrich slowly loses his smile and realizes what a dull formal ritual their interaction has become.

Lubitsch was himself heterosexual, but as has been stated, he was quite skilled at miming all the parts in a film, including the female ones. More important is the fact that his films often undermine normative notions of gender, sometimes in ways that might also be read as queer.[4] Above all, we find sympathy in his films for outsiders and non-conformists. In his comedies he often let them triumph, but in this film we are especially moved because the lovers cannot overcome the social structures that conspire to make their love “impossible.”

Works Cited

Ashkenazi, Ofer. Weimar Film and Modern Jewish Identity. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012. Print.

Bogdanovich, Peter. “Movie of the Week.” New York Observer, 20 Sep.1999: 16. Print.

Boyarin, Daniel, Daniel Itzkovitz, and Ann Pellegrini, eds. Queer Theory and the Jewish Question. Columbia UP, 2003. Print.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Dir. Robert Wiene. Perf. Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, and Friedrich Feher. Decla-Bioscop, 1920. DVD.

Chávez, Ernesto. “‘Ramon is not one of these’: Race and Sexuality in the Construction of Silent Film Actor Ramón Novarro’s Star Image.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 20.3 (2011): 520-44. Print.

“Drei Atelier-Tage in Hollywood: Ernst Lubitsch an der Arbeit bei Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.” Film-Kurier, 19 Apr. 1927: 2. Print.

Drössler, Stefan. “Ernst Lubitsch and EFA.” Film History 21.3 (2009): 208-228. Print.

“Ernst Lubitsch wird in Berlin drehen?” Film-Kurier, 12 Feb. 1931. Print.

Eyman, Scott. Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. Print.

“Gespräch mit Ernst Lubitsch. Die Film-Operette—Ein schönes Märchen.” Film-Kurier, 1. Beiblatt, 1 Jan. 1930. (Interview dated 15 Dec. 1929.) Print.

Hake, Sabine. Passions and Deceptions: The Early Films of Ernst Lubitsch. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1992. Print.

Hall, Mordaunt. Revs. of The Student Prince. New York Times 22 Sep. and 25. Sept 1927. Print.

Hansen, Miriam. Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1991. Print.

Huff, Theodore. An Index to the Films of Ernst Lubitsch. Special Supplement to Sight and Sound. Index Series No. 9. London: British Film Institute, Jan. 1947. Print.

Jäger, Ernst. Rev. of The Student Prince. Film-Kurier, 11 Sep. 1928. Print.

“Kommt Lubitsch nicht zurück?” Film-Kurier, 27 Apr. 1923. Print.

Kracauer, Siegfried. From “Caligari” to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1947. Print.

Kurtz, Rudolf. Rev. of The Student Prince. Lichtbild-Bühne,11 Sep.1928. Print.

“Lauds Producing Here: Mr. Lubitsch Praises Finished Work on Settings—Films and Moral Tendencies.” New York Times, 18 Sep.1927. Print.

Novak, Ivana, Jela Krečič, and Mladen Dolar, eds. Lubitsch Can’t Wait: A Theoretical Examination. Ljubljana, Slovenia: Slovenian Cinematheque, 2014. Print.

Rogowski, Christian. “Ein Schuss Champagner im Blut. Ludwig Bergers musikalische Filmkomödie Ein Walzertraum (1925).” Filmblatt 51 (2013): 2-12. Print.

Rosenberg, Joel. “Shylock’s Revenge: The Doubly Vanished Jew in Ernst Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be.” Prooftexts 16 (1996): 209-44. Print.

Schallert, Edwin. Rev. of The Student Prince. Los Angeles Times, n.d. (probably Sept. 1927). Audrey Chamberlin Scrapbooks, Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills. Print.

Schuster, Aaron. “Comedy in Times of Austerity.” In Novak et al., eds. Lubitsch Can’t Wait. 19-38. Print.

Soares, André. Beyond Paradise: The Life of Ramon Novarro. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002. Print.

“Streit um ‘Alt-Heidelberg,’” Film-Kurier, 30 May 1927.

The Student Prince of Old Heidelberg. Dir. Ernst Lubitsch. Perf. Ramón Novarro, Norma Shearer, and Jean Hersholt. MGD, 1927. VHS.

Thompson, Kristin. Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood: German and American Film after World War I. Amsterdam: Amsterdam UP, 2005. Print.

————. “Lubitsch, Acting, & the Silent Romantic Comedy.” Film History 13.4 (2001): 390-408. Print.

Tully, Jim. “Ernst Lubitsch.” Vanity Fair (Dec. 1926): 82. Print.

Underhill, Harriet. Rev. of The Student Prince. New York Herald Tribune, 22 Sep. 1927. Print.

Variety. Rev. of The Student Prince. 28 Sep. 1927. Print.

Weinberg, Herman G. The Lubitsch Touch: A Critical Study. Orig. 1968. Third Revised and Enlarged Edition. New York: Dover, 1977. Print.

Žižek, Slavoj. “Lubitsch, the Poet of Cynical Reason?” In Novak et al., eds. Lubitsch Can’t Wait. 181-205. Print.

[1] See Thompson, “Lubitsch” 403. She asserts that Shearer was “not up to her role,” citing this scene, and yet at various points in the same article, she cites evidence that Lubitsch acted out all the parts for actors in his films (397, 399), and the actors were then supposed to try to imitate what he had mimed for them (this comes up again and again in interviews with actors who worked with him). She also cites Eyman (134), who writes that Lubitsch’s editor for this film, Andrew Marton, stated that Lubitsch felt that neither Shearer nor Novarro were right for the film. That may have been true, but given Lubitsch’s exacting directing style, it is hard to believe that either actor would have done anything without his approval. Bogdanovich, by the way, writes that this performance by Shearer is the best of her career.

[2] One might also read Shearer’s performance—in which she followed Lubitsch’s direction—as standing in for all the American women who were infatuated with Novarro during the late 1920s. And as for a powerful gaze, well, in “real life,” of course, Norma Shearer did arguably have more power than Ramón Novarro, given her connection to MGM management and his status as a foreign actor who was a closeted gay man.

[3] On Ramón Novarro, see Chávez and Soares. On the ambiguous gender and sexual positioning of the first “Latin lover” in America, Rudolph Valentino, see Hansen 243-94.

[4] On the ways in which Jews, homosexuals, and women have been similarly positioned in Western culture, and how anti-Semitism, homophobia, and misogyny have often worked in similar ways, see Boyarin et al.