Precarious Intimacies: Narratives of Non-Arrival in a Changing Europe

TRANSIT vol. 11, no. 2

by Maria Stehle and Beverly Weber

Abstract

The representation of intimacy in depictions of immigration exists alongside histories of deeply racist contacts and connections. Yet intimate connection may also produce moments of joy, sustaining solidarity and resistance to violent forms of exclusion. In this essay, we develop the notion of precarious intimacies through readings of three films depicting the journeys of refugees to Europe: In this World (Michael Winterbottom, 2002), Ein Augenblick Freiheit [A Moment of Freedom] (Arash T. Riahi, 2008), and Can’t be Silent (2013). The desire for Europe as a “happy object” (Ahmed 2010) propels these journeys, but the films narrate stories of non-arrival which reveal the unhappy consequences of encounters with European border regimes. We consider precarious intimacies both as aesthetic strategies as well as reading practices that call attention to the realities of racialized exclusion while still gesturing to possibilities of contact and compassion.

Introduction

With the recent rise in refugees fleeing the civil war in Syria, politicians and media are again posing the question: how will large numbers of refugees change the face of Europe? Such speculations range from expressions of fear about how an influx of mainly Muslim refugees, traumatized by violent conflict, could pose risks to European safety and security, to hopes that the arrival of a younger population will help ease the economic burden of an aging European population.1 These reactions serve a range of national political agendas; in this context, it is increasingly important to emphasize the complexities of Europe’s migration histories, including its own colonial legacies, its racism and violence, as well as its lived multiethnic realities.

Scholarship, too, must develop to address the large body of films over the last decades depicting refugee journeys from the Middle East to Europe, films that often invite the spectator into the political situation affectively via intimate connections represented on screen. Given the ease with which such intimacies may reinforce existing relationships of power and violence between Europe and its refugees, in our analyses we highlight alternative ways of thinking about how global migrations continue to transform and decenter Europe. Our strategies of reading place refugee experiences of migration and intimacy in relation with racism in European regimes, systemic exclusion, and Europe’s colonial past. We develop the notion of precarious intimacies as a way of understanding both aesthetic strategies and reading practices that aim to call attention to the realities of racialized exclusion, but also gesture to possibilities for connection and compassion. We chose three films, Michael Winterbottom’s fictional documentary In this World (2002), Arash T. Riahi’s fiction film Ein Augenblick Freiheit [A Moment of Freedom] (2008), and the German documentary film Can’t be Silent (Julia Oelkers, 2013) due both to their variety of formal approaches, as well as their common thematics. These films were made over the course of a decade and reflect different socio-political moments, yet all depict disrupted or halted journeys of refugees on their way from the Middle East to Europe. The stories they tell highlight moments of intimacy and connection, but also draw attention to how intimacies are embedded in forms of precarity.

Feminist conceptions of precarity have developed in part as a response to activist movements such as Precarias a la Deriva that have mobilized new solidarities around precarity and insecurity. These theorizations focus on the impacts—including the profound destruction of social bonds—of insecure access to resources in connection with informal and feminized labor (Precarias a la Deriva). Notions of precarity have expanded in fruitful ways to encompass differential exposure to injury, violence, and death (Judith Butler in Puar 169–170); precarity is a category that “denotes social positionings of insecurity and hierarchization” and “accompanies processes of Othering” (Isabell Lorey in Puar 165). For migrants and refugees, precarity results from insecure residency status, differential exposure to imprisonment and surveillance, economic exclusion, and racialized physical violence. Under these conditions, forming intimate connections is a strategy for survival even as such networking highlights the precarious conditions in which refugees live.

Precarious intimacies rely on an understanding of intimacy that rejects a division of private and public spheres that would relegate intimacy to the private. We draw partially on the work of comparative literary scholar Lisa Lowe in The Intimacies of Four Continents, in which she examines the relationship between settler colonialism, transatlantic slavery, and modern liberalism. Lowe suggests that intimacies are a “particular fiction” that constantly shifts and transforms in response to material conditions and historical moments (Lowe 21). As Lowe points out, colonial formations of violence and power were created in tandem with the production of notions of intimacy. Such notions of intimacy relied on a sense of interiority that could be possessed by a liberal subject, viewed as accessible only to the white subjects of Europe and North America (36). The intimacies of four continents of her title, embedded in racialized violent colonial relationships, were sublated by the private notion of intimacy that racialized non-European populations, in part through a distancing from norms of family and reproduction, as well as through exclusion from processes of “freedom” and “progress” (36). Racialized narratives prohibit the legibility of “emergent” intimacies that consist of the “implied but less visible forms of alliance, affinity, and society among variously colonized peoples beyond the metropolitan national center” (19). The emergent intimacies Lowe describes comprise relationships of close connection that exist across immense geographical distance, and are often obscured.

Our notion of precarious intimacies responds to a different archive and a different time period than Lowe’s. Lowe examines a particular period when a now obsolete understanding of intimacy as possession of interiority came to obscure the meaning of intimacy as close connection between seemingly disparate peoples and processes in the context of colonialism (18-19). Our archive consists of contemporary European films, and our strategy is to trace intimacies in the sense of closeness and familiarity between people, and consider how those intimacies are embedded in the material conditions of precarity, marked as they are by racism, state violence, and economic insecurity, all of which have a historical relationship to the colonial processes Lowe explores. The violence of state power and EU border regimes become visible as they clash with ephemeral moments of care, touch, and affection that highlight existing violence and enable potential alliance and resistance to such violence. Under such conditions, precarious intimacies represent forms of connection and solidarity as survival strategies, and make legible the forces that produce precarity. Reading for precarious intimacies allows us to recognize and articulate how intimacies are always embedded in forms of racialized violence even as alliances and affinities present moments of defiance against violent exclusion.

European Films of Journey and Migration

European fiction and non-fiction films of the first decades of this century abound with stories of journeys to and through Europe, journeys triggered by fear and marked by violence and war, journeys that are interrupted, journeys that fail, journeys without destination, and imagined arrivals that are never achieved.2 European cinema scholar Guido Rings understands such examples of “migrant cinema” as providing “answers that might help to improve integration and community cohesion in Europe” (1). He reads “the fluid and transgressive character of migrant protagonists” as “particularly fruitful for the elaboration of mindsets” that address the challenges of globalization, migration, and rightwing populism (1). While we do not dispute the importance of films that depict the stories of migrants as a way to push back against the spread of rightwing populist fears, the political function of these films for a presumed liberal European audience needs to be problematized. Indeed, it is important to recognize that representations of migration and intimacy in European film often produce a hierarchy in which a white Europe(an) functions as a savior figure. In her analysis of the commodification of ethnicity in European cinema, Ipek Celik-Rappas critiques the way in which films “present images of innocent and victimized refugees in order to raise compassion for the liberal spectator” while filmmakers are praised “for saving refugees and their suffering from anonymity” (83). We argue that alternative models of intimacy that do not rely on the compassion of the (white) European may question and decenter Eurocentric thought and politics by highlighting the violence they produce. Furthermore, most journey films as a genre depend on the “affectively-invested zone of expectations” (Berlant 2) that places hope in a particular narrative of arrival, in this case in Europe, as a safe space and a space of potential prosperity. Yet the films we discuss in this essay refute expectations of arrival in a European space that offers safety or an end to economic or political precarity.

The journeys of refugees we trace in the following depict containment and incarceration on the way toward Europe as well as stasis, immobility, and the threat of deportation within Europe. Such stories of non-arrival take many forms, but they all paint a picture of a Europe that has erected fences and spaces of exception both outside of and within its borders (Bayraktar 3). Spaces of non-arrival are related but not identical to Randall Halle’s “interzones,” ideational spaces in which Europe is figured in productive moments of transit (Halle 4–5). Spaces of non-arrival include make-shift hotels, container homes, camps, offices, and lines, as well as the more visible vans, boats, and beaches. Europe itself is a space of non-arrival for people who receive only temporary residency or who are perpetually excluded from entrance or confined to refugee spaces. In these spaces, stories intersect and people’s lives touch despite the isolation and uncertainty produced. Often, the narrative expectation of arrival in a safe (and European) space is thwarted; simultaneously, the films tell stories of intimate connection and encounters that are possible in spite of European border regimes. The challenges to the European border regimes offered by these films form a critique of global regimes of racist exclusion by which Eurocentric notions of who is allowed to enter and who deserves to stay continue to produce and re-produce forms of colonial, racialized violence.

All three films start with the premise that the idea of Europe draws people towards it. This desire for Europe takes the form of a desire for a “happy object” (Ahmed); however, the films focus on revealing the unhappy effects not of this desire, but of the realities that face refugees who must contend with migration regimes that prohibit their physical security as well as economic and political participation in Europe. Happiness in Europe comes to seem impossible in these films; we emphasize those brief moments of precarious human connection that happen in spite of, or even in resistance to, violent exclusion.

The Journey as Perpetual Space of Non-Arrival: In this World (2002)

In this World, a docudrama by the British filmmaker Michael Winterbottom filmed on digital video, won the Golden Bear at the 2003 Berlin International Film Festival and is considered one of the first European films to feature refugees as main characters (Celik-Rappas 84). The film reconstructs the journey of a teenage boy, Jamal, and his cousin Enayat, from an Afghan refugee camp in Pakistan on their way to Europe. Although the film focuses on the cousins’ shared journey, only Jamal actually arrives in Europe. At the end of the film, Jamal, hidden in a container ship, enters Europe illegally. In Italy, he tries to make money to pay for his journey to England by attempting to sell goods to tourists, but he is also shown pick-pocketing. Once he has arrived in England, the camera offers a close-up of Jamal’s face as he is speaking to his family, attempting to convey the bad news: that his cousin died during their shared journey in the shipping container.

At the time the film was made, Afghans who had fled the political violence that ensued after the Soviet invasion including the shifting political tensions between Mujahedeen and the Taliban, populated refugee camps across the Afghan border in Pakistan such as the one in which Jamal and Enayat lived. New camps were created in this longstanding structure after the US invasion (Khan; Kronenfeld). Winterbottom makes this history explicit in the opening voiceover narration of the film. Although the genre of the film has been described as “documentary realism” (Lykidis 37), In this World also questions “generic conformity” (Farrier 226) and expectations of refugee documentary films in focusing not on arrival but rather on the “condition of perpetual displacement” (Farrier 223). Further, In this World is a fictional reenactment, but it plays with documentary authenticity in its use of lay actors and original locations (see Farrier) and in its retracing of a very common migrant route. The final minutes of the film, over the voice of Jamal praying, show inter-titles explaining what happened to the actor who played Jamal, a refugee himself, and revealing that the film is a reconstruction of the actual events that befell him. The actor experienced a similarly difficult journey and was not granted asylum in England, but was permitted to stay as an unaccompanied minor until he came of age. The concluding scenes emphasize the actual historical situation, but also the framing voice and agency of the European film team.

The “didactic, highly politicized voiceover” which cites statistics and facts, stands in tension with the personal and fictionalized story of the journey of two cousins (Loshitzky 121-2). The British-English narrator establishes the male voice of the European as the authority calling attention to the plight of refugees. These facts situate the personal and intimate story of Jamal and his cousin Enayat in its global context, but also shift agency from the refugees to the European observer.

The journey depicted in the film, however, focuses almost entirely on the refugees and the people they encounter on their journey. European characters are largely absent in In this World (Lykidis 37), even though the dream of arriving in Europe, the dangers of the journey to Europe, and the violence of ‘fortress Europe’ shape Jamal and Enayat’s journey. The absence of Europeans in any human interaction has contradictory effects: On the one hand, Europe can remain the happy object since it is never actually unveiled as anything but a desire; on the other hand, European spaces are void of personal connection or interaction. The dangerous attempt to enter “fortress Europe” illegally proves deadly for Jamal’s cousin Enayat. Jamal enters Europe isolated and alone. Europe’s politics of exclusion disrupt familial relationships, connection, and intimacy.

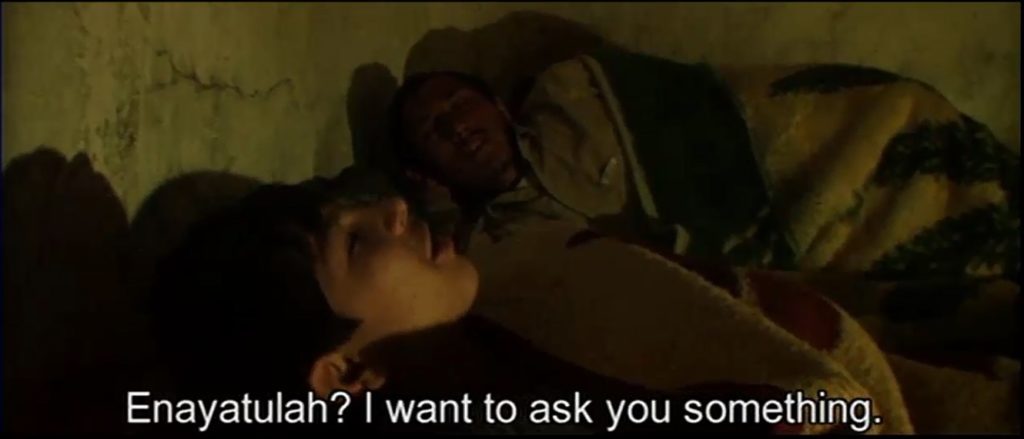

Before entering Europe, as Jamal and Enayat are pushed onward in their journey by a network of pre-paid human traffickers, their close personal relationship sustains them. The camera tracks Jamal and Enayat’s movement and lingers on intimate moments with the gaze of an observer. The stills in Figures 1 and 2 highlight the close-ups In this World uses to evoke intimate moments of human interaction that take place in spite of a journey that is marked by exploitative business transactions. Toward the beginning of the film, for example, Jamal and Enayat fall asleep in the same bed, sharing stories about the invention of music, familial conflict and drama. The close-up of the camera conveys an unusual sense of intimacy and family connection, safety and security (Figures 1 and 2). The hand-held camera, used throughout the film, is particularly shaky at this moment. It serves as witness and intruder into this scene, calling attention to its existence with exaggerated movements. These home-video aesthetics highlight the sense that viewers are witnessing something almost too personal, a documentation of a family moment. The viewer occupies an uncomfortable position of intrusion rather than an invitation to action to “save” as these moments of connection and care take place in spite of the insecurity and violence that drive—and disrupt—the journey.

Other representations of physical closeness in dangerous spaces belie the closeness and security produced in moments of intimate connection: trips in the confining space of vans, and the journey on the container ship that many refugees, including Enayat, do not survive. A sequence of close-ups of Jamal illustrates his connections with people that assist him and his cousin. As Jamal and Enayat get help crossing the border into Turkey from Kurdish villagers, an older woman pats Jamal on the head, expressing sympathy for him; she “caresses his head gently, then feeds and nurtures him” in what Loshitzky describes as gestures of “maternal care” (125). His head, again, comes into focus when his hair is washed and cut upon their arrival in Istanbul—but at this moment, the touch seems painful and Jamal grimaces (Figure 2). In the final scene, when Jamal makes the phone call to his family to convey the news that he has arrived in England without Enayat, the camera also focuses closely on his head and hair. This tight framing highlights Jamal’s vulnerability throughout these brief moments of contact between the teenager and others.

While the film might show that Jamal’s “vulnerable body […] that faces closed borders and comes face to face with death is the one deserving to be in Europe” (Celik-Rappas 85), it is also clear that his arrival and temporary status do not mean a less precarious life for him. He arrives alone and without any familial support. Thus “close” and intimate spaces, either in Europe or on the journey to Europe, move between safety, security, and connection, as well as pain and violence. The short-lived intimacies provide only fleeting solidarities, but insist on attention to the precarious conditions under which Jamal and Enayat move.

Ankara as a Space of Non-Arrival: Ein Augenblick Freiheit (2008)

Released five years after In the World, the Austrian-French co-production Ein Augenblick Freiheit [A Moment of Freedom] focuses on a route from Iran through Ankara, Turkey, with Austria, Switzerland and other locations in Western Europe imagined as the ultimate destinations. The film is set in a complex historical moment: in the wake of the 2004 and 2007 eastward expansions of the EU, as well as in the aftermath of the Iraq invasion, and at a time when Turkey had begun to fulfill the terms of its pre-accession agreement by implementing EU migration policies. These developments reduced and disrupted refugee migration to both Turkey and the EU, producing new “precarious transit zones” and preparing the conditions for the new figure of the transit migrant (Hess). In this film, individual stories of survival and death on refugees’ journeys—in this case fictional, though with roots in the director’s own experience—connect to global political questions about the ethical treatment of refugees. The UN building in Ankara where the fates of many refugees’ lives are decided most prominently indicates this global connection.

The film traces the fictional, dramatic fates of three groups of people who meet for the first time in Ankara because they live in the same apartment building. None of them leaves Ankara intact. The grey color scheme and gloomy lighting creates a dreary feeling; color enters the film by way of a few pieces of clothing, only to highlight the otherwise bleak surroundings and living conditions. The first quarter of the film shows the dangerous journey of Iranian refugees in Ankara; the majority of the film is then set and filmed in Ankara, a decidedly Turkish national space transformed into a transnational space where people of many ethnicities and origins live in what are clearly legible as legal and material non-spaces, shabby hotels and small rooms where they try to set up what might resemble a make-shift home for themselves and their families or friends. The film is framed by a scene of a public execution by an Iranian firing squad, first filmed from above and then cut to zoom in on one of faces of the condemned. At the beginning of the film, the camera zooms in on the face of a terrified looking woman. At the end of the film, we see the bloodstained face of Abbas, one of the Iranian refugees, whose denial of asylum and deportation to Iran leads to his execution. An asylum decision, the film suggests with this framing, is a decision over life and death.

The first of the three groups the film follows is formed by Manu and Abbas: a younger Iraqi Kurd and an older Iranian Kurd who end up, by coincidence, living together in one small room as they await decisions on their asylum applications. They live as a family unit of sorts, as is illustrated by a scene where Manu tries to cook a meal of poultry for Abbas and himself. Manu catches—steals—a swan in the local park and kills and cooks the bird in a giant pot, as white feathers cover their apartment. In general, Manu appears to take care of Abbas, who often seems discouraged and tired. Manu, in contrast, has an eternally optimistic attitude, sends fake Polaroid photographs to his Kurdish village showing him with expensive cars and blonde women, and is not afraid to use unconventional, illegal, means to secure the next step in his and Abbas’ journey.

Manu’s naïve exuberance is challenged powerfully in a scene on a city bus. Although Manu and Abbas can only communicate with one another in English, they discover a Kurdish song that they both know. In a rare moment of joy, Abbas sings the song together with Manu. Mid-song, Turkish riders on the bus attack them for speaking Kurdish, yelling “speak Turkish, speak Turkish,” as they beat the two. Anti-Kurdish Turkish nationalism, a legacy at the heart at the founding of Turkey in the image of Europe, interrupts their performance of a sort of familial intimacy in song.

After learning that Abbas’ asylum status has been denied, Manu organizes a fake visa for Abbas without telling Abbas that it is fake. After the first encounter with border agents, they dance and sing in their small train compartment (Figure 3), believing that they have safely entered the Schengen zone. Their celebratory dance is interrupted as the border agents reappear and arrest Abbas. We do not see any of the intervening moments that will end in Abbas’ death as one of the three people executed by firing squad in the frame scenes; Manu also seems to remain ignorant of Abbas’ fate. Manu’s almost carefree and most certainly naïve desire to care for him thus nurtures an important intimacy that sustains Abbas, but is also partially responsible for his deportation to Iran. In the film, Abbas’ death appears as a de facto collusion between the violence of European border regimes and the Iranian regime itself. When Manu arrives in Germany, he is shown roaming around Berlin’s Alexanderplatz. The camera moves in fast panoramic shots, circling the square and then Manu’s face, relaying excitement and disorientation, relief and sadness, as we witness brief imagined scenes from his future, all of which show moments of touch: physical contact with characters that have not appeared in the film thus far. Intimacy, it is suggested, is also his vague hope for a future after the loss of Abbas, but the forms that it might take are yet to be determined.

just before Abbas is arrested.

were held captive.

The second group of characters consists of the Iranian couple Lale and Hassan and their young son Kian. Visually overshadowing their relationships is the UN building, a place to which Hassan frequently returns, and in which he repeatedly expresses his desire to provide his family with a better life. Hassan hides the denial of his asylum claim from the family as they fantasize about a future in which the current regime is overthrown in their home country and democracy is established. Shortly thereafter, Lale and Kian follow Hassan to the UN, and witness from afar as he first tries to steal someone else’s papers, and then stabs himself in order to appear “tortured.” This effort also fails to gain him an entry visa to a European country. Hassan finds himself trapped between the violence of the European border regime and the threats that face him should he return to Iran. Seeing no other choice to protect his family, he burns himself to death in front of the UN building, an act misread by the Turkish media as terrorism rather than protest. Although Lale and Kian are then granted their visas, they return to Iran via the same dangerous route by which they came. Hassan’s actions represent a series of failures to protect his family, a protection he imagines as only possible upon entry to Europe. His investment in Europe as a space of arrival (and, perhaps, his investment in a role as “protector” of the family) ultimately facilitates the destruction of the intimacies that motivate his actions.

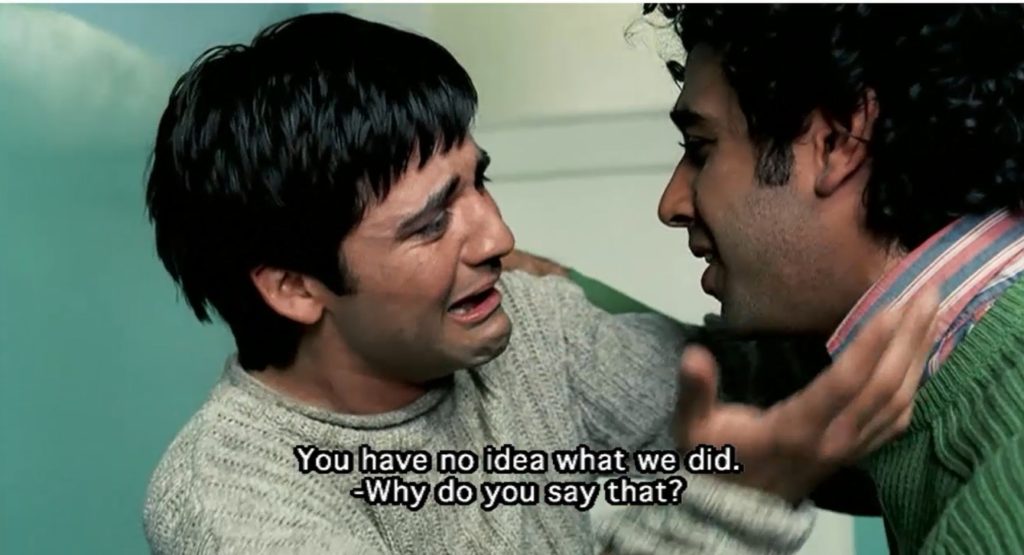

The third group of characters is another temporary family grouping. Two young men, Ali and Merdad, take on parental roles as they care for two children, Merdad’s niece and nephew. After a dangerous journey, they, too, arrive in Ankara to live in the same make-shift hotel, and they, too, wait in line in front of the UN building. In Ankara, Ali is captured and tortured by people that appear to be agents of the Iranian secret service, though they seem primarily interested in capturing the children’s parents who already live in Austria. Together with the two young children, Ali is held until his discovery and rescue. Merdad, after finding out that his friend and the children were taken, can do nothing but wait in line in front of the UN building. Ironically, the very fact that this abduction happened and was reported to the UN helps the children and their companions to speed up the process of attaining visas. In an argument after Ali and the children are released, Ali accuses Merdad of neglecting them in favor of his Turkish girlfriend. In this scene, Ali and Merdad argue like jealous parents until Ali learns that Merdad secured their release and cries in Merdad’s arms (Figure 4). Ali and the two children arrive in Austria to be reunited with the children’s parents. Merdad decides to remain in Ankara with Jasmin. Their provisional familial grouping falls apart as visas granting entry into Europe prompt a reformulation along more traditional family lines, leaving Ali isolated. In this story, moments of intimate connection between the characters are subject to multiple systems of power, including the underground economy of refugee housing in Ankara, the Iranian state apparatus, and the UN.

The film oscillates between an overwhelming sense of hope and even love and joy, and a sense of hopelessness, fear, and endless exclusion. The director, Arash T. Riahi, also sees the film as “a reaction to and commentary on the political and social situation in Europe today, where racism and hatred of foreigners has become acceptable to a frightening degree” ( “Director’s Statement”). Against the exclusions of contemporary Europe, Riahi proposes a strategy of depicting “universal desires” and dreams (ibid.). Riahi’s rhetoric of universal desires and dreams certainly appears naïve, but the film itself undercuts any notion of universal experiences of desires, dreams, and freedoms in its portrayal of the ways in which state violence marks out the limits of intimacy and safety. In the face of narrative trajectories that constantly challenge its characters’ beliefs in finding a better life, whatever this might mean, touch opens up moments of intimacy that ground and sustain the characters. The moments depicting Merdad’s love for Jasmin; powerful, non-biological familial bonds; and the (in some cases) unbearable burden of love in the face of danger matter because they push back against regimes of exclusion that leave little space for the intimacies that sustain human lives. These moments, whether we consider them as moments of joy, happiness, or hope, are intimacies rendered precarious by multiple levels of institutional violence (EU border regimes, state violence, and other racialized violence) as this violence becomes all the more legible in contrast to them.

The way in which this film portrays intimacy, however, stands in tension with viewer expectations. The stories of non-arrival that this film tells are marked by moments of interruption and diversion, as well as moments of personal, intimate connection and friendship. They rely on the temporal interruption of the journey, while the moments of intimacy are brief strategies of locatedness and connectedness against their precarious lives. These moments often turn out not to be of use, at least not to reach a specific destination; on the contrary, they might hinder or further endanger the journeys migrants plan to undertake or the goals they have. Again, it is important to emphasize that we describe moments—echoing the title of the film, Augenblicke [moments]—because the framing scene of execution inevitably brings the viewer back to violence and isolation. It is precisely the momentary nature of love and caring touch that reveal the violence of Europe at work in the film.

Ein Augenblick Freiheit depicts a variety of detours, diversions, and returns. Some of the refugees are sent away, some get stuck and turn back, some decide to take different routes. Most dramatically, one story ends in a desperate protest-suicide and another in the political execution of an Iranian refugee who is sent back to Iran. In spite of the violent outcomes of two of the three stories, characters are shown forming loving and compassionate connections and family units while they reside in Ankara. Ein Augenblick Freiheit not only shows suffering and vulnerability, but emphasizes moments when the characters defiantly display agency even though neither their destination nor the spaces of non-arrival they pass through or land in during their journeys in any way guarantee their bodily integrity. The film offers the clearest critiques of Europe’s racialized forms of exclusion by contrasting forms of state violence with these moments of defiant strength and connection, relief and even joy. As in In this World, the happy object Europe does not enable such moments; rather these moments depict chosen community and familial solidarity outside of Europe and in defiance of violent exclusion. Intimacies depicted in these films rework family structures in creative ways rather than merely ending with their rupture.3

European Spaces of Non-Arrival: Can’t Be Silent (2013)

The German documentary film Can’t Be Silent focuses on characters who, though they have arrived in Europe, are stuck in refugee centers and camps as they await decisions in their respective asylum cases. The film thus reveals the ways in which refugee lives are also made precarious by the very restriction of movement and forms of exclusion refugees encounter within Europe. Can’t be Silent reflects a post-Iraq War reality of asylum seekers in Europe, at a time when asylum claims made by people from the Middle East were increasingly being rejected. The film revolves around a music-activism project initiated by the German Band Strom&Wasser. Documentary filmmaker Julia Oelkers filmed the band’s attempt to bring musicians who lived in different refugee camps across Germany together to tour as a musical group (as Strom&Wasser featuring The Refugees). Throughout the successful tour, almost all the artists face threats of deportation. While the filming of Can’t be Silent (2013) pre-dates the arrival of a larger number of refugees fleeing the Syrian Civil War, its release and reception coincide with discussions in the EU about closing the Schengen Zone borders towards the South and East to ward off refugees from Syria. German chancellor Angela Merkel’s refusal to cap the number of refugees Germany would accept triggered—and continues to trigger—controversies in Germany and Europe.

Can’t be Silent contains what could be considered clichéd images commonly seen in documentary films critical of European refugee policies and politics. Some of the interviews with the protagonists are held in their own living spaces: in crowded refugee homes and behind fences, but also in the small shared apartments occupied by some with more stable statuses. These spaces are juxtaposed with interviews in public spaces as refugees explore their limited freedom of movement within the often-rural towns in a gray and unwelcoming Germany.4 The main focus of the film is the music project, the band’s practice sessions, and the musicians’ tour across Germany. This tour allowed many of the refugees who at that time were legally confined to their assigned local areas to gain special permission to travel within Germany, meet and connect with each other, and make new friends. Europe, in this film, is a space of exclusion and uncertainty, but it also is a space in which refugees build a diasporic community. This adds yet another layer of meaning to the precarious intimacies we discuss here: where In this World shows how intimate spaces and connections can swiftly change from safe to violent, and Ein Augenblick Freiheit focuses on Ankara as a space of precarious intimacy, in this film, precarious intimacies specifically reveal the perpetual spaces of exclusion within Europe, and the moments of connection that nevertheless emerge within and against structures of violence and exclusion. Even while physically located within Europe, refugees remain in spaces of non-arrival; their recognition by the state remains token and minimal. Most importantly, refugees remain excluded from opportunities for personal, financial, and physical security because of the ongoing threat of deportation. The close personal relationships they form in their diasporic communities are closely tied to the precarity of their legal and economic status in Europe.

In spite of the film’s focus on music performed in Germany, Germany is not a space of arrival within the film. This is particularly visible when the German government awards the initiator of the music project, Heinz Ratz, a medal for integration. The film records the journey of Revelino, one of The Refugees, to the award ceremony, beginning with his nervous presence in the train station: “The train station is always a problem for us, because you might be controlled any time, especially if you are the odd man out, someone of a different skin color.” During the award ceremony, Hosain and Revelino, the only two of The Refugees in attendance, are nearly completely silent. Maria Böhmer, at the time the Commissioner for Integration in the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, gives the award to Ratz with only a generic nod to the two musicians present as “your musicians,” asking the audience to participate in an exoticizing gaze by inviting the audience to “look at them.” Later, she stages photos shaking their hands, never bothering to learn their names.

In the scenes depicting the award ceremony, Can’t be Silent thus stages a failure to meet the expectations of its title. Ratz uses his acceptance speech to draw attention to the precarious circumstances produced by German asylum law which at the time greatly limited mobility, made it difficult to acquire paid work, and rendered many of the musicians in his band vulnerable to uncertainty or deportation. Yet the refusal to be silent promised by the title proves impossible for the two refugees in attendance. The camera lingers on Hosain and Revelino who listen and smile awkwardly; after the award is granted to Ratz, Hosain but not Revelino, shakes Böhm’s hand for a photo. The word inscribed on the award, “integration,” is juxtaposed with the image of the two eating alone at a table, separated from the rest of those in attendance (Figure 5).

The meaningless handshake and the refugees’ visible separation from other attendees highlights ongoing experiences of exclusion. The refugees’ music becomes an unreciprocated gesture of shared cultural experience as intimacy. Hosain and Revelino remain unrecognized by representatives of the state who render them exoticized, nameless, voiceless Others while awarding recognition to the German man who organizes the project. The reward ceremony, then, seems to be a replication of a white savior trope. The refugees are doubly silenced at the award ceremony; their music is replaced by a spring quartet playing classical music as they silently witness Ratz’ award; they remain appropriated for a discourse of “integration” even as their presence highlights the impossibility of creating new forms of belonging in the overtly symbolic national space of the German chancellery. The defiant intimacy of diasporic subjects is confronted with the impossible intimacy of “integration.”

The precarious intimacies in the film complexly reveal the insecure conditions under which refugees live, but they also highlight the shared connections that form through music. Music becomes a form of sonic touch through which people connect. Their shared music illustrates shared lives that take place in a perpetual state of non-arrival. This intimate togetherness between musicians from Gambia, Ivory Coast, Afghanistan/Iran, and Dagestan is translocal. As the musical connection between the Afghan rapper, Hosain, who arrived in Germany from an Iranian refugee camp, and the Dagestanian rapper MC Nuri, who grew up in a refugee camp in Germany, demonstrates, this music project yields unexpected transnational convergences. And yet, despite the project’s success, the musicians continue to face likely deportation.

Another precarious intimacy is the friendship between the Afghan rapper Hosain and his friend Meisam. The two men met on their dangerous journey to Europe and remain in touch while moving around to different camps and detention centers within Germany. When they meet again in Hamburg as part of the musicians’ tour (Figure 6), Hosain and Meisam recount their journey to Germany: the dangerous and overcrowded boats and people they saw drowning in the Mediterranean. The background of the Hamburg harbor signals their location in Germany, but also hints at their precarious status as asylum seekers, the perpetual danger of being deported, and the dangers that face them should they attempt to return after deportation. Throughout the film, the friends meet in various locations, but also continuously face separation as they are moved to different camps in different locations.

Hosain’s discussions after a rap performance at an outdoor festival illustrate the way in which music creates a sense of connection and intimacy for a diasporic community in Germany. A celebratory mood accompanies conversations among Afghanis attending an event that is part of an emerging Afghani contemporary music scene which is also distributed widely through YouTube, in which Hosain plays a major role. As he stands with his arm around Hassan, who appears to be of middle school age, Hassan explains in German that he has been in Germany only for three months. Hosain follows with an admonition to youth “that we don’t say, he is Pashtun, he is Uzbek, we don’t care about such divisions. Only when we are united, we can rebuild our country.” The camera then cuts to Hassan rapping one of Hosain’s songs, then back to the crowd jumping and dancing to Hosain’s performance. Hosain’s music has become a galvanizing force for the formation of an Afghan diaspora. The precarious intimacies in this film reveal the emergence of transnational diasporic spaces of connection within Europe, in the face of the continuous uncertainty refugees experience in Europe.

Touching Journeys and Intimate Spaces of Non-Arrival

In these three films, global intimacies inflect the kinds of affective connections and intimacies that Europe as a space of encounter produces and precludes on interpersonal levels. If, as Lowe points out, the emergence of political liberalism was accompanied by violent intimacies between continents as well as potential solidarities and affinities, these films track how such intimacies move towards and into European space, and literalize them in the touch and connection between figures marked as non-European. Cinematic narratives of precarious intimacy highlight the structures of exclusion in Europe and the destruction of social bonds that occur as part of the insecurity faced by refugees. Intimacy thus forms fleeting potentialities marked by connection, affection, even love, against the forms of violence structuring the relationship of Europe to its migrants and refugees.

Most characters in these films do not arrive in the Europe they sought out as their original destination; the characters arriving in “Europe” arrive under different circumstances than they planned and remain in spaces of non-arrival. These narratives of spaces of non-arrival thus do not offer different ways of thinking about—or imagining—a better Europe. They defy appropriations of the migrant as a “tool” for making Europe “better” but insist on claiming spaces of care, love, and connection, in spite of and against the regimes of racist exclusion that continue to define Europe. If many European films about migration “present European identity as always already complex, transnational, and decentered” (Bayraktar 9), these films contain moments of community and attachment that locate contemporary refugee migration, currently so important for European politics and politicking, as outside the purview of the European identity project altogether. The precarious intimacies of these films are certainly marked by the exclusions produced by the idea of Europe, but the affective community identifications at work in spaces of non-arrival function outside of or at least at a slant to identifications with Europe.

Moments of intimate connection do not take place in Europe, but are suspended in spaces on non-arrival; this means that such affinities and connections cannot be easily appropriated for a narrative of a newly emerging and morally improved Europe. Their precarity always also points to the racial othering of refugees and their differential exposure to violence and death, even as their intimate connections offer moments that suggest global forms of solidarity and cohabitation.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. The Promise of Happiness. Duke University Press, 2010.

Bayraktar, Nilgun. Mobility and Migration in Film and Moving Image Art: Cinema Beyond Europe. Routledge, 2015.

Berghahn, Daniela. “No Place like Home? Or Impossible Homecomings in the Films of Fatih Akin.” New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film, vol. 4, no. 3, Feb. 2007, pp. 141–157.

Berlant, Lauren Gail. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press, 2011.

Butler, Judith. “Precarious Life, Vulnerability, and the Ethics of Cohabitation.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, vol. 26, no. 2, Apr. 2012, pp. 134–151.

Celik-Rappas, Ipek. “Refugees as Innocent Bodies, Directors as Political Activists: Humanitarianism and Compassion in European Cinema.” Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Sobre Cuerpos, Emociones Y Sociedad, vol. 0, no. 23, Apr. 2017, pp. 81–89.

Farrier, David. “The Journey Is the Film Is the Journey: Michael Winterbottom’s In This World.” Research in Drama Education, vol. 13, no. 2, June 2008, pp. 223–232.

Gopalakrishnan, Manasi. “‘Islamic State’ Reportedly Training Terrorists to Enter Europe as Asylum Seekers.” DW.COM, 14 Nov. 2016, http://www.dw.com/en/islamic-state-reportedly-training-terrorists-to-enter-europe-as-asylum-seekers/a-36389389.

Hackensberger, Alfred. “Das nächste große Schlachtfeld ist Europa.” DIE WELT, 29 June 2015, https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article143186475/Das-naechste-grosse-Schlachtfeld-ist-Europa.html.

Halle, Randall. The Europeanization of Cinema: Interzones and Imaginative Communities. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Hess, Sabine. “De-Naturalising Transit Migration. Theory and Methods of an Ethnographic Regime Analysis.” Population, Space and Place, vol. 18, no. 4, July 2012, pp. 428–40. Doi:10.1002/psp.632.

Hockenos, Paul. “OPINION: Refugees Will Change Europe for the Better.” Al-Jazeera, http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/10/refugees-will-change-europe-for-the-better.html. Accessed 15 May 2017.

Khan, Muhammad Abbas. “Pakistan’s National Refugee Policy.” Forced Migration Review; Oxford, no. 46, 2014, pp. 22–23.

Kronenfeld, Daniel A. “Afghan Refugees in Pakistan: Not All Refugees, Not Always in Pakistan, Not Necessarily Afghan?” Journal of Refugee Studies, vol. 21, no. 1, 2008, pp. 43–63.

Loshitzky, Yosefa. Screening Strangers: Migration and Diaspora in Contemporary European Cinema. Indiana University Press, 2010.

Lowe, Lisa. The Intimacies of Four Continents. Duke University Press Books, 2015.

Lykidis, Alex. “Minority and Immigrant Representation in Recent European Cinema.” Spectator-The University of Southern California Journal of Film and Television, vol. 29, no. 1, 2009, pp. 37–46.

Oelkers, Julia. Can’t Be Silent. good!movies, 2013.

Precarias a la Deriva. “Adrift on the Circuits of Feminized Precarious Work.” Feminist Review, vol. 77, 2004, pp. 167–71.

Puar, Jasbir. “Precarity Talk: A Virtual Roundtable with Lauren Berlant, Judith Butler, Bojana Cvejić, Isabell Lorey, Jasbir Puar, and Ana Vujanović.” TDR/The Drama Review, vol. 56, no. 4, Nov. 2012, pp. 163–177.

Riahi, Arash T. “Director’s Statement.” Ein Augenblick Freiheit, http://p106906.typo3server.info/51.0.html?&L=1. Accessed 4 May 2017.

————. Ein Augenblick Freiheit. autofocus films, 2009.

Rings, Guido. The Other in Contemporary Migrant Cinema: Imagining a New Europe? Routledge, 2016.

Thöne, Eva, and Maria Feck. “Das sind die neuen Europäer.” SPIEGEL ONLINE, 1 Mar. 2017, http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/gesellschaft/fluechtlinge-in-europa-das-ist-das-projekt-the-new-arrivals-a-1136048.html.

Winterbottom, Michael. In This World. Channel Home Entertainment, 2003.

1 See, for example, Gopalakrishnan; Hackensberger; Hockenos; Thöne and Feck.

2 See, for example: Terraferma (Emanuale Crialese, 2011), Fuocoammare/Fire at Sea (Gianfranco Rossi, 2016), Welcome (Philippe Lioret, 2009), #MyEscape (Elke Sasse, 2016), Land in Sicht (Antje Kruska, Judith Keil, 2013), Willkommen auf Deutsch (Hauke Wendler, Carsten Rau, 2014), Neuland (Anna Thommen, 2013) – to list just a few. For a detailed discussion, also see Yosefa Loshitzky, Screening Strangers.

3 In this sense, the films align with Daniela Berghahn’s argument that in films depicting diasporic families “transnational mobility […] is undeniably a force that transforms the structure and identity of the family, yet it does not necessarily result in its fragmentation and rupture. Even where journeys end in death and separation, as they often do, these experiences give rise to new beginnings and new alliances” (Berghahn 80).

4 One of the most controversial aspects of Germany’s asylum laws has been the Residenzpflicht which allowed the restriction of asylum seekers to the community to which they were assigned, often even after receiving some sort of asylum status. These restrictions on movement were significantly liberalized in 2015, but the 2017 Integration Law introduced new means of restricting refugee residency.