Modeling a World City

Modeling a World City

TRANSIT vol. 12, no. 1

Deniz Göktürk

The question of migration and border control has become a litmus test for governments, democracies, and civil societies around the world in recent years. In our era of highspeed digital connectivity people acquire knowledge about the world primarily as long-distance spectators through moving images flickering on portable screens. The common framing of migrants moving in a caravan or huddled on an overcrowded boat is occasionally punctuated by a photograph gone viral, for example, of the drowned Syrian boy on a Turkish shore or the crying little girl from Honduras at the US-Mexican border, looking up her mother’s legs as a guard is patting her down. These images have made a stronger imprint on the public perception of crisis than any research publication on migration. Meanwhile, the question arises if saddening images of dead or distraught toddlers in red t-shirts are effective in mobilizing affective engagement with the human cost of violent borders. Moreover, it is unclear whether such spectatorial empathy can translate into critique and action. The direct appeal of framed helpless children offers first and foremost a safe outlet for shock and pity that affords no political intervention or systemic change. The victimizing gaze on migrants falls short of imagining possibilities of coexistence, collaboration, and a shared future. Are there alternatives to passively watching the pain of others, the suffering of refugees detained at borders, rescued at sea, or trapped in camps? What might the world look like through the lens of migration? And how can we begin to conceptualize an open city based on participation and interaction?

Framing migrants

Native (settled, indigenous) and migrant figures in the 21st century are by no means given, they evolve in highly complex mediations and beg reconceptualization in academic research, public debate, and visual culture.[1] Berlin based cultural anthropologist Regina Römhild has critiqued the tendency in migration research to “(re)produce […] subject categories and concepts of the nation-state which it […] aims to criticize.”[2] By producing a “plethora of accounts of migrants’ lives and migrants’ worlds,” Römhild argues, social research as well as public debate have tended to pit those who cross borders against the petrified notion of a native population, construed as bounded and rooted in nation-state territory. Such accounts reinstate native permanence irrespective of previous histories of mobility across regions. Resisting “migrantology,” Römhild and others have promoted critical migration studies that reverse the viewing direction: looking at the “naturalized center” from the point of view of its “ethnicized and racialized margins.” Such a shift in perspective reveals the allegedly stable core of the nation “as being part of a postmigrant, postcolonial space of cultural dynamics and social struggles” thus cosmopolitanizing migration research and turning it into “a general study of cultural and social realities crossing ethnic and national bounds” (Römhild, 69). The critique of migrantology is pertinent to understanding the power dynamics of visibility and invisibility, which determine the framing of migration in visual media. Despite the wide spread rhetoric about access, interactivity, and participation in the digital age, key questions concerning the transnational traffic in (re-)presentation and performance are far from conclusively resolved today: Who is looking? Who stages and frames whom for whom? Which places deserve promotion as recognizable locations, and what links them to other places through montage in a cinematic geography?

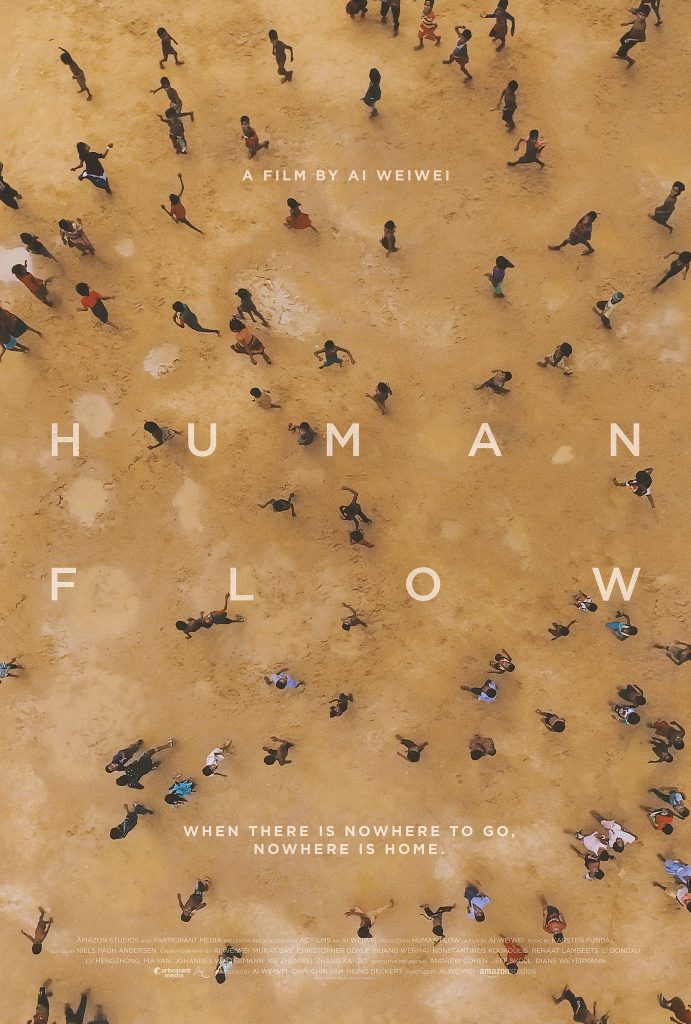

Camps in drone vision

Performances of migrant figures in feature films or video installations that set out to counter dominant media representations operate in a field of vision that is saturated by images. A prominent example is Weiwei’s film Human Flow (2017), which chronicles the migration crisis on a global scale with an abundance of references to news media reports. As a Chinese dissident, Ai Weiwei rose to super-stardom in the international art-world, operating globally, even while under house arrest in China. His first self-directed documentary feature Human Flow lists 12 production companies in Germany, the US, China, Palestine, Jordan, Iraq, Turkey, Bangladesh, Mexico among others, along with 12 international distributors. The 140-minute film made the shortlist for an Academy Award for Best Documentary; it is streaming on Amazon, iTunes, and YouTube. During two years of filming, the crew travelled to 40 refugee camps in 23 countries. The documentary incorporates footage shot by drones, iPhones, and 12 credited cinematographers, including Ai Weiwei himself. Throughout the film, the alternation between aerial and ground-level perspectives is a key structuring feature, moving from shots that display the expanse of camps from the air to scenes that approach individual migrants on the ground as they walk, rest or talk about their experiences. The film thus zooms in and out between micro and macro perspectives, between close-ups and long shots or aerial views. The epistemological tool of zooming in and out can be learned from moving images; it is key to a new kind of scalable global imagination.

Ai Weiwei frequently enters the picture himself, interacting with migrants as well as governmental and non-governmental representatives. This emphatic-empathetic self-positioning of the artist in midst of distraught refugees converges with his public image as an exile.[3] Does Ai Weiwei’s film present an example of “migrantology” in the sense of exhibiting displaced people for the voyeuristic gaze of viewers in front of their television or computer screens in cozy living rooms? Ultimately, Human Flow cannot escape the predicament of making marginalized people visible: an act of representation that typecasts others in their pain. To be fair, the film does aspire to a systemic vision beyond the display of individual suffering. It makes a point of showing landscapes of migration—natural and built environments turned inhospitable by climate change or war, such as a Kenyan desert that yields no crop or a Syrian city in rubbles. The film gives a stage to many voices from around the globe. In its polyphony, Human Flow aims to evoke more than pity and tears, it sets out to promote comprehension of the driving forces of migration and the profound structural inequities that prevail in a world reigned by capitalism. In its global scope, however, Human Flow cannot capture locally specific inflections in depth and runs the risk of melding “all global refugee experiences into one tragic narrative.”[4] Clearly, Palestinians settled in Gaza and Lebanon have different histories and face different challenges than Syrians or Rohinga fleeing civil war today. Insisting on commonalities and melding all these locations together creates a delocalizing effect on the viewer.

The drone is a much-hyped innovation in media technology, which allows for disembodied aerial vision and long-distance warfare.[5] In Human Flow, the deployment of drone cameras in regions that have been subjected to drone warfare creates an uncanny effect. Does the film align itself with a military technology of precision bombing that has resulted in the loss of civilian lives or, as some have called it, “collateral damage”? Why drones? Are the filmmakers simply indulging themselves in the common trend of “drone infotainment” (Kaplan, 164)? If yes, does their deployment of the totalizing gaze from above bear resemblance to the removed vision of tactical weaponry? What does the drone see that the human eye cannot? In capturing the extensive scale and the geometric layout of the camps, the drone shots make visible the uniformity of tents or containers and the dehumanizing leveling of all individuality in these settlements. The film hovers in the air and depicts the experience of refugees “from a high vantage point,” as George Didi-Huberman points out.[6] Looking at the world through this particular framing of migration conjures up a picture of the world as camp.[7] While the film shows Ai Weiwei engaging with refugees on ground-level in many scenes, the drone vision betrays a flattening of diverse individual experiences. The Syrian man with whom Ai Weiwei performatively exchanges passports in Idomeni will remain entrapped in the camp while the artist holds the privilege to air travel; he can insert himself as a participant observer and subsequently return to his studio in Berlin. Ultimately, we are left with questions about the limits of universalizing gestures and humanitarian empathy.

New tools for building world pictures

Beyond the movement of people, the term “flows” have become a much used metaphor in describing the circulation of resources and products, images and messages, ideas and ideologies, technologies and techniques in globalization around the modern world.[8] But does the old saying of panta rhei (everything flows) help us explain how “policy debates occurring around world trade, copyright, environment, science, and technology set the stage for life-and-death decisions for ordinary farmers, vendors, slum-dwellers, merchants, and urban populations,” as anthropologist Arjun Appadurai asked almost twenty years ago (Appadurai, Grassroots Globalization, 2)? In our current climate of nationalist entrenchment, we still have to ask ourselves: what are “the peculiar optical challenges” and “institutional epistemologies” that have created a disjuncture between academic and vernacular discourses about the global? In what ways can educational institutions and the arts counteract the growing fragmentation into social media bubbles? More importantly, how can we reconfigure the interplay between “pedagogy, activism, and research” in a way that would be more inclusive to “grassroots globalization” or “globalization from below” (3-4)? In order to overcome “the growing disjuncture between the globalization of knowledge and the knowledge of globalization,” Appadurai’s call for a true internationalization and democratization of research cultures seems more important than ever: “actors in different regions now have elaborate interests and capabilities in constructing world pictures whose very interaction affects global processes” (13). Making room for these kinds of “world pictures” will entail creating a new toolbox in order to reimagine how people relate to the land, the city, and to each other. Such reimagination will require attention to the ways in which architecture channels flow. What roles can the artist or academic play to avoid the high vantage point when it comes to the presentation of material produced by disenfranchised populations?

The sound of a world city

In the following, I would like to contrast Ai Weiwei’s cinematic approach hovering above the ground “from a high vantage point” with the practice and optics of building a “world city” in collaboration with refugees. The exhibition Weltstadt – Erinnerung und Zukunft von Geflüchteten im Modell[9] was designed in Berlin the same year that Ai Weiwei’s film was released. Unlike Human Flow, Weltstadt did not put any migrants on the screen. The exhibition stands out for avoiding pictures of suffering migrants, and focusing instead on a joint project. Rather than looking at migrants, this installation proposed to look at the world through the lens of migration as a source of imagination. It presented a captivating and effective model for an intersectional space, based on shared memory and a vision for a participatory future. I saw Weltstadt at Agora Berlin in Neukölln where it was on show 12 May to 5 June 2017. A digital presentation of pictures and sounds from the exhibition is a perfect fit for TRANSIT’s special topic on “Landscapes of Migration,” as it allows us to emphasize participatory and creative aspects in environmental design and cultural production.

The assemblage of model buildings, initiated by S27 – Kunst und Bildung, an art laboratory based in Schlesische Strasse 27 in Berlin-Kreuzberg, was designed by a diverse group of participants in collaboration with designers. Between September 2016 and March 2017, young people from Egypt, Afghanistan, Albania, Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Iran, Iraq, Kosovo, Lebanon, Mali, Morocco, Mauretania, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, Chechnya, and Ukraine, most of whom were living in refugee shelters across Berlin, had worked for three to four weeks each in eight fixed and mobile workshops installed in the Berlin districts of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, Lichtenberg, Neukölln, Pankow, Spandau and Tempelhof-Schöneberg as well as Genshagen (Brandenburg) and constructed 130 model buildings, all at a scale of 1:10 and inspired by their memories or their visions for the future. The models were built with simple means, using cardboard, wood and recycled materials. The artist and curator Matze Görig, alongside architects from raumlabor berlin and sound students from Hochschule der populären Künste, then staged the model buildings in an installation, creating a spatial arrangement that viewers could walk through. Dynamic lighting and sound added a cinematic quality to the walk-through experience. The world city thus imagined and built collaboratively creates a new spatio-temporal configuration that carries traces from the past but remakes them as part of a new ensemble for the future. The exhibition concept explains: “A petrol station on the outskirts of Aleppo, a school building outside Mogadishu, a fortified tower in Damascus: When in foreign lands, people who have fled their home often tend to reach for their smartphone to show others photos of their homelands – but also photos of places they have passed through along the way and of their new surroundings. Each of the photos arouses memories, fears and hopes which then take concrete form in the models they have constructed. Places of remembrance have been created, their visions are now tangible. Berliners and guests from all over the world are invited to take a walk through World City and hear the stories of those who built it.”[10]

Beside the changing light that dynamically illuminated buildings from inside and simulated different times of day, it was indeed this polyphony of voices speaking in English, German, Farsi, Arabic, and French, transmitted through speakers placed among the buildings, that animated the world city. In conversation with the artistic director, the sound designers explain: “by having the sound coming from in between the houses, you get the impression that the whole city actually comes alive with the voices of people, rather than having the audio material split from the houses themselves. A surround system would have entailed this physical distance between the houses and the voices, which give them life. Finally, we had four speakers on each exhibition surface, positioned in such a way that one would have a clear listening experience from any position within the room.” [11] Beyond the human voice recordings, the soundscape also included other elements: “Rather than a simple background, the sound design became part of the narrative told by the interviews, from a simple natural atmosphere, it turned into a more abstract form, containing different leitmotifs, surreal atmospheres, small melodies, all conceptually very closely knit to the spoken word content.”[12] We can hear individual voices saying things that are coherent in themselves. The viewer/listener is charged with following threads and relating sound bites, fragments of stories, and visual impressions. The project thus attempts to return coherency to a representational trope, in which the city is seen as composed of incoherent, fragmented, and cacophonic sounds.

Walking through these neighborhoods assembled from models, I felt drawn into the fragmentary stories in multiple voices and languages, returning to particular sites multiple times to hear more and gain orientation in the model city. The first sentence in the audio recording strongly stands out as a motto to this collective soundtrack: “I belong to my memory, not to my country, not the way it is now. I don’t belong there.”[13] Wherever “there” might be, we understand that that place must have changed beyond recognition; memory is all that remains. ‘Heimat’ no longer denotes one place but becomes a portable feeling, a memory that can be reactivated in conversation. Another voice says: “I did not choose to be here. I just found myself here to be honest.” The deictic reference to “here” could imply a number of meanings: here as in the model building workshop, here as in Berlin, here as in the model world city, here as in Germany, here as in Europe, here as in the world. The composition of these short statements in constellation accentuates the respective relativity of “here” and “there” and invites visitors to conceive of the world on a more continuous scale.

One speaker explains his model of Bab Sharki, the Eastern Gate, one of the seven gates of Damascus: “A long time ago the city centre was surrounded by walls and it had seven gates. It was like a castle. This was one of those gates. It’s the most well-known one and it still stands to this day. It did get destroyed a little, but they repaired it. If you go at night, it’s a really calm place and it’s really beautiful, it reminds you of how people were back then, how they lived and how it was difficult for them to do certain things.” […] “If I could choose, I would choose a Damascene house. A Damascene house is a big house with a wonderful fountain in the middle. I used to have a house like this. It had eight rooms, it was really cheap, and I was hosting almost 25 people in it. It was wonderful.” […] “My property got destroyed. It’s gone. It went with the shelling. Rockets, fighter-jet rockets. I don’t actually feel so sorry about it because there were many other people who lost their homes at the same time. I think the war changed my perspective on owning tangible and material things…”

Beyond memories of architecture back home or experiences of violence and persecution the soundscape also includes comments of political analysis: “The Gulf countries bought a lot of guns. But it wasn’t only them, Turkey, Iraq, all of them… I guess it was a really good market and part of the privileges enjoyed by people over here is down to that, because of all the wars. I mean, they didn’t do it for charity.” Or: “You fight for your freedom and you get some things, but when you come here it’s completely different. Everything is so free in a way, you feel you have so much freedom that you don’t know what to do with it.” Or: “If you get down to the basics, this is not about freedom, it’s about rights, human rights. Having a good education, a job, being able to do the things you like doing, these are all rights, not freedom.”

Other remarks address the new environment: “Berlin is such a bubble. It accepts everyone, it ignores everyone. You never feel like you’re being observed here. You could actually walk down the street naked and no one would even look at you.” […] “There are no boundaries. It’s a massive city, it’s very diverse, but I also think the city is losing some of its identity because of that somehow. But to be fair, Berlin has been the least racist place I’ve been to.” […] “German society should not be so obsessed with how to integrate these people. They should be more interested in how they can contribute to society.” […] “I live with one person from Somalia and one from Liberia, it doesn’t matter at all. And when one of us has a bit less money, we all cook together.” […] “Ce qui me dérange c’est la Ausländerbehörde.” Overall, the soundtrack presents an affirmation of our “postmonolingual condition”[14] where the participants of “welcome classes” and integration courses can speak in the language of their choice, not every sentence needs to be translated, not everyone understands every word spoken but there is nonetheless some degree of convergence in polyphony.

The world city modeled in Weltstadt is not what urban sociologists have called a “global city” in the economic sense, a conglomeration of headquarters for transnational finance, information, management, and specialized service industries. In fact, we could read the installation as presenting a counter model to the global city conceived as a nodal point in the world market. The world city staged in Weltstadt is not focused on the concentration of global finance but on the urban imaginaries of its residents from around the world, presenting the city as a site of creative collaborations and potential recalibrations of movement and settlement.

Weltstadt subsequently became a mobile project; it was shown in the London Design Museum, Görlitz and Spandau. More recently, it formed part of the street festival in central Berlin celebrating the Day of German Unity, October 1st-3rd, 2018. Under the motto “Nur mit Euch” (Only with you), this festival aimed to highlight civic engagement and participation as key aspects of a vision for coexistence and collaboration. In this context, the exhibition was staged in a former bumper car range where visitors could use binoculars to look at details. As the presentation shifts from walk-through to more removed vision – the slideshows offered in our electronic journal present a further stage of removal – the question of ownership becomes more pertinent. Where are the model builders now? Who do their models belong to when the world city becomes spectacle? Can we as cultural brokers avoid the tourist gaze “from a high vantage point” and preserve some of the participatory potential of this project?

Employing a participatory model, the Weltstadt exhibitions presented a decentered approach to urban design and knowledge production. The collective imagination and composition of a world city, based on a range of shared memories and visions woven into the urban fabric, challenge the viewer to rethink categories of native and migrant in their respective relationships to place and time. The assemblage of world pictures from here and there into a world city highlights the significance of both materiality and creativity coming into productive interplay in a shared practice. Putting art produced by refugees on display is clearly not enough. As artists and academics, we can draw inspiration from the collaborative process in the production of Weltstadt. With the digital remediation in TRANSIT, we hope to at least broaden the exhibit’s reach. As the conversation continues, we will have to keep listening. Building a world city remains a work in progress.

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford University Press, 1998, “The Camp as Biopolitical Paradigm of the Modern”: Pp. 119-188.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

————. “Grassroots Globalization and the Research Imagination.” Public Culture, Volume 12, Number 1, Winter 2000, Pp. 1-19

Clifford, James. “Varieties of Indigenous Experience: Diaspora, Homelands, Sovereignties,” in: Marisol de la Cadena and Orin Starn, eds. Indigenous Experience Today. Oxford: Berg, 2007: 197-223.

————. Returns. Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Harvard, 2013.

Didi-Huberman, George. “From a high vantage point.” Eurozine. 12 October 2018.

Kaplan, Caren and Parks, Lisa, eds. Life in the Age of Drone Warfare. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2017.

Kaplan, Caren. “Drone-O-Rama. Troubling the Temporal and Spatial Logics of the Distance Warfare” in Life in the Age of Drone Warfare. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2017. Pp. 161-177.

Phillips, Charlie. “Making Drama out of the Refugee Crisis.” The Guardian. 1 April 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/apr/01/refugee-films-another-news-story-stranger-in-paradise-island-of-hungry-ghosts

Römhild, Regina. “Beyond the bounds of the ethnic: for postmigrant cultural and social research.” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture, 2017, Vol. 9, No. 2. Pp. 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2017.1379850

Weiwei, Ai. “The Refugee Crisis isn’t about refugees. It’s about us.” The Guardian, 2 February 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/feb/02/refugee-crisis-human-flow-ai-weiwei-china.

“Weltstadt | World City.” Schlesische 27. Kunst und Bildung. http://www.schlesische27.de/s27/portfolio/weltstadt/

Yasemin Yıldız, Beyond the Mother Tongue. The Postmonolingual Condition. Fordham University Press, 2012.

[1] For a discussion of the “indigenous” today and its interrelations with “diaspora” see: Clifford, James. “Varieties of Indigenous Experience: Diaspora, Homelands, Sovereignties,” in: Marisol de la Cadena and Orin Starn, eds. Indigenous Experience Today. Oxford: Berg, 2007. Pp. 197-223. See also: James Clifford, Returns. Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Harvard, 2013.

[2] Römhild, Regina. “Beyond the bounds of the ethnic: for postmigrant cultural and social research.” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture, 2017, Vol. 9, No. 2. Pp. 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2017.1379850

[3] See, for example: Weiwei, Ai. “The Refugee Crisis isn’t about refugees. It’s about us.” The Guardian, 2 February 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/feb/02/refugee-crisis-human-flow-ai-weiwei-china.

[4] Phillips, Charlie. “Making Drama out of the Refugee Crisis.” The Guardian. 1 April 2018.

[5] Lisa Parks and Caren Kaplan, eds. Life in the Age of Drone Warfare. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2017. Esp. Caren Kaplan, “Drone-O-Rama. Troubling the Temporal and Spatial Logics of the Distance Warfare.” Pp. 161-177.

[6] Didi-Huberman, George. “From a high vantage point.” Eurozine. 12 October 2018.

[7] This depiction resonates with Giorgio Agamben’s claim that the camp rather than the city is the biopolitical paradigm of the West, and the state of exception has become the rule. Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford University Press, 1998, “The Camp as Biopolitical Paradigm of the Modern”: Pp. 119-188.

[8] Cf. Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

[9] See: “Weltstadt | World City.” Schlesische 27. Kunst und Bildung. http://www.schlesische27.de/s27/portfolio/weltstadt/

[10] See: Project description.

[11] See: http://www.hedd.audio/en/weltstadt-world-city/

[12] Ibid.

[13] The 45-minute long soundtrack is streaming online: http://audiodesign.hdpk.de/?nor-projects=ausstellung-weltstadt-erinnerung-und-zukunft-von-gefluechteten-im-modell

This and the following quotes I selected from the soundtrack are primarily in English, mostly due my own linguistic limitations. See TRANSIT’s own rendition here: http://transit.berkeley.edu/2019/weltstadt/.

[14] Cf. Yasemin Yıldız, Beyond the Mother Tongue. The Postmonolingual Condition. Fordham University Press, 2012.