Lessons from the Southern German Borderlands

TRANSIT vol. 14, no. 1

H. Glenn Penny

Abstract

This essay engages the borderlands region joining contemporary Austria, Germany, and Switzerland as a ‘central periphery’ in the heart of Europe. As a region in which multiple and varied notions of belonging have long stretched across the borders that animate our modern political maps, the most important borders shaping the inhabitants’ sense of belonging were often in their heads. By drawing on five eclectic museums in the region, where these notions of belonging are being articulated and produced, the essay underscores some of the region’s key characteristics that historians of nation-states have frequently overlooked, but ethnologists generally have not. It argues that directly engaging those characteristics offers us productive ways of globalizing European and German histories that scholars regularly ignore when considering the implications of provincializing or decolonizing them. The essay also argues that this process has the potential to upend the historiography centered on European nation-states and their empires.

Introduction

After writing a global German history that decentered the nation-state and sought to include Germans and German communities from around the world, I have been drawn to what I have been calling the southern German borderlands, for lack of a better term.[1] Much of what I analyzed among German communities outside of Europe—especially their cultural multiplicities, their linguistic flexibility, their mobilities, and their polycentrism—are readily apparent in this region as well. More concentrated, and with greater temporal depth, they have forced me to rethink what I thought I knew about German history.

The designation ‘southern German borderlands,’ however, is highly problematic. It implies that there is only one border, between the German nation-state (or the kingdoms and other states that preceded it) and Austria and Switzerland, when, in fact, there are a great many borders crisscrossing the region between Salzburg and Basel, most of which cannot be found on political maps, and few of which everyone can or could see. It might be more useful to think of this swath of territory as the southern regions of German-speaking Europe. Yet that too has its limitations, since language is seldom as unitary or exclusive as this designation might imply. Moreover, much like our more general dependence on political borders for marking space, it plays all too easily into the cunning teleology of the nation-state. We could simply term this region the center of Europe, as a recent book on Switzerland has done.[2] It would be more accurate, however, to label it a “central periphery,” given that so many of the places in the region seem to be both centers and peripheries, and the German speakers not only speak varied forms of German but also other languages and/or dialects.

That is what most interests me: I am enamored with the linguistic complexities, cultural multiplicities, and forms of polycentrism across this region over the last two centuries, which, truth be told, I had largely overlooked in my earlier projects. There are, in fact, entire histories, German histories, that I as a putative historian of Germany knew little about until recently, and which, as I came to know them, led to some productive rethinking of what I thought I knew.

In part, that rethinking has led me to ponder the layers of history in the southern German borderlands and its many phantom landscapes, as Kathleen Conzen might have called them. Like the overlapping cultural, linguistic, and former political borders, some people recognize these historical landscapes that others cannot see, shimmering below the contemporary surface.[3] This rethinking has also led me to examine the region’s simultaneous histories more closely during the modern era, and it has forced me to reengage questions of belonging in German-speaking Europe.

To give you a sense for what intrigues me, I would like to offer you a series of vignettes tied to five eclectic museums, all of which provide us with different windows into the layered histories of a region peopled by an ever-changing mix of inhabitants who turn out to have been (and to be) rather worldly provincials. At the same time, however, these institutions have been and remain sites for the active (re)-cognition of cultural landscapes. They not only reflect but also contribute to the multiplicity of their localities and have a profound impact on the mental landscapes of their visitors. This includes fundamental recastings of notions of belonging and even local inhabitants’ basic understandings of pronouns such as ‘us’ and ‘we.’

Interconnected Obergünzburg

A good place to begin is in Obergünzburg, an inauspicious town in the eastern Allgäu. Most readers probably know little about the town or the region, since the town has a population of less than 7,000 people, and the Allgäu never became a political region or a state. Still, the people who live there know they belong in both, just as they know that Obergünzburg is not only in the Allgäu but also in Swabia (Schwaben), or at least that part of Swabia that is currently within the borders of Bavaria, which was once a kingdom, and as most readers will know, is now one of the states in the Federal Republic of Germany. So, Obergünzburg is a typical Allgäuen, Bavarian, German, Swabian town located a little more than 100 kilometers from the Bavarian capital of Munich.

There is no direct train line from Munich to Obergünzburg, or even a train station in the town, so it is challenging to get there without a car. Consequently, most people would regard it as a provincial town, even if its residents and neighbors consider it a municipal center for the surrounding villages. Like most German hometowns, it has a center, and three buildings which stand at the heart of that center:

The first two, the St. Martin’s Parish Church and the Heimat Museum, meet most expectations for the region; architecturally, symbolically, and in the narratives they promulgate about the town and its surroundings.

The third building, however, is a squat modern structure of glass, bricks, and horizontal wood siding filled with ethnological artefacts collected around the turn of the twentieth century by Captain Karl Nauer, a local who worked for Nord Deutsche Lloyd in the Pacific Ocean. Nauer collected widely for multiple ethnological museums, and he donated part of his own collections to his hometown before WWI. He also helped to get much of what he had donated to the large ethnological museum in Munich returned to his hometown after the city fathers clamored for it during the teens and twenties.

These collections, among others from outside Europe, have been part of the town’s history for over a century. Today, the new museum building, which opened in 2009, teems with school children, who come to this cultural center from surrounding villages. When they arrived during my visit in 2021, the staff told them that after they entered the elevator in the front room, they would travel through the earth to the Pacific. Then, when those elevator doors opened, they entered the displays. The verisimilitude was effective. While the history of the collections is intriguing, what they do for local children who grow up in such a provincial place may be more telling: they come into life with affinities for the Pacific and an understanding that their rural community has global affiliations. Unlike for most of us, and most other Germans, both the Allgäu and the Pacific are on their mental maps, coupled together by this institution and the histories it tells visitors about the interconnections between the Pacific collections and the other materials in the Heimat Museum, which are cast as interrelated parts of the town’s patrimony. Indeed, I suspect that this small museum, with its focused displays and local audiences, has a much greater impact on its visitors and its extended community than an institution as large as Munich’s Museum of Five Continents, which is only one of the dozens of museums in the city. Additionally, its Pacific collections are only one of its many collections, and most of its objects are not on display.

Just as some of the people in the Allgäuen, Swabian, Bavarian, German town of Obergünzburg feel a connection to the Pacific, other people in the Allgäu, which is crisscrossed by borders rather than inscribed by them, feel themselves at home in Württemberg, Austria, Tyrol, and Vorarlberg, which is, and is not, a part of Austria (more on that assertion below). Some of their ancestors spoke, as well, of belonging to a Tyrolean and even a Vorarlbergian nation, but never an Allgauer nation. That is because there never was one. But that did not mean they did not belong to, or rather in, the Allgäu.[4]

Understandably, this notion of belonging to a multiplicity in a locality would make perfect sense to Obergünzburg’s neighbors, since its connection to the Pacific is the only piece of these multiplicities of belonging unique to that town. The insightful ethnologist Hermann Bausinger repeatedly underscored much the same about a great many locations in Baden-Württemberg, which overlaps with the Allgäu.[5] Over the course of a career that began shortly after World War II, and only ended with his passing in 2021, Bausinger consistently reminded us that if people in southern Germany managed to fashion a sense of unity around regions or states, it was always a unity filled with difference and variety.

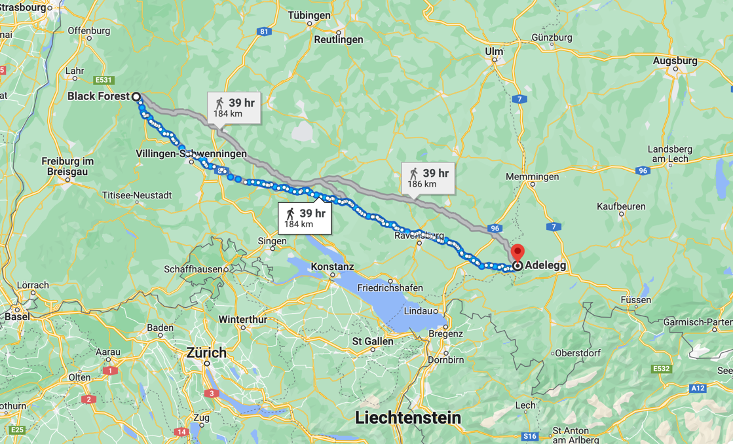

The 100 km trip from Isny in the Allgäu to the edge of the Black Forest, Bausinger liked to explain, takes the traveler across at least a half dozen cultural and natural areas. Along this trip, there are neither massive geographical markers, nor huge mountains, nor vast plains. Rather, there are ever-shifting natural landscapes and a plethora of borders, although most of them are absent from our political maps. Across this region, as Bausinger put it, “there are economic areas and settlement landscapes whose edges do not coincide with either the external political borders or the internal political divisions.”There are also clear confessional, cultural. and linguistic borders. None of them match up exactly with the political boundaries, in part because they are more “boundary bundles [Grenzbündel] rather than boundary lines.” As such, they are more open than closed, and rather than functioning to isolate people within tiny enclaves, they are, and always have been, provocative, producing “interconnections—through friendships, curiosity, business interests.” In that sense, “’small border traffic’” in this part of the world was never the exception, it was and still is “the rule.”[6]

One of the chief implications of these complexities and multiplicities is that transgression has long been commonplace in this part of the world. Consequently, ongoing experience with confessional, cultural, and linguistic differences was normal as well. Moreover, if borders here were always meant to be crossed, the ones that most mattered in people’s lives were those cultural and linguistic ones that people could feel rather than the political ones demarcated by states.

The reason those state-imposed borders mattered less, is because many cultural groups existed across them. Bausinger reminded us that people in Bauland, Tauberland, and Hohenlohe, are all Franconian [Frankish], which distinguishes them from people in the nearby middle Neckar region, even as that complex subjectivity connects them to people on the other side of the Bavarian and Hessian borders. When he met with poets who wrote in the Franconian dialect during one of his studies, for example, he noted that they came from a variety of locations: “the border,” which divided the political states under whose auspices they lived, as he put it, “didn’t matter,” because they were not only bound together by their language “but also a certain way of life and a consciousness or sense of belonging.”[7]

Bausinger wrote similar things about Swabians and other groups in the region, and what he called the “centrifugal neighborhood relations,” which tied such diverse groups together in a variety of locations around places such as the Bodensee [Lake Constance], or the “three-land-corner” near Basel, where France, Germany, and Switzerland have come together for as long as those states, or earlier versions of those states, existed. There has been a great deal of work on the economic and cultural relations in that three-state region, which was always interconnected across the borders that divide it, much as there has been some fantastic work on the Bodensee region, which also is part of, yet extends across multiple political borders.[8] Both of these locations, in other words, are cultural centers situated on political peripheries.

Yet one of Bausinger’s most poignant observations was that in many parts of this landscape, the borders that most mattered were in people’s heads. Those included the outlines of Hohenzollern, which had been a permanent fixture on maps for centuries before postwar politics erased its borders and eliminated that entity, while creating Baden-Württemberg as one of the federal states in the new West Germany (although the family castle, ostensibly the most visited castle in the country, is still there). That landscape memory makes sense. 1945 was not so long ago, and we can easily find the territory of Hohenzollern on twentieth-century maps. There are even people alive today who recall being there, and who know, of course, when they are in that past place now.

Yet other people are also aware of being in Hohenzollern when they travel through it (or where it was, depending on your perspective), and many more know when they are in Vorderösterriech. Sometimes translated as anterior or outer Austria, it once comprised administrative districts of the Habsburg Empire far from its borders and well into southern Germany. Stone border markers remain on the landscape. I have seen some, for example, in the woods not too far from Tübingen. Not so long ago, they designated the division of the land between the Habsburg Empire and Württemberg. Ever shifting, those Austrian auspices in southern Germany were not officially eliminated until 1805, but for the places where they most mattered before that geopolitical shift, they continue to matter today. That former designation gives those places within it a distinction, much as Obergünzberg’s unique relationship to the Pacific does. All those distinctions serve to remind us of the region’s deep federalism and its distrust of central authorities, as Dieter Langewiesche has written about so convincingly. It also reminds us of the cultural polycentrism animated by what might better be termed a varied array of cultural provinces rather than provincial cultures. That, at least, is how Bausinger saw it, and I think he was right.[9]

He was right as well when he stressed that the classic things we associate with these local cultures, Swabian spätzle noodles as much as the Pacific Island ethnographic collections in Obergünzburg’s city center, frequently came from somewhere else. That was true for Christianity as well, and it was true for the inhabitants. Most stem from people who came from elsewhere. In part, that is why it has been so difficult, even futile, to try to definitively map dialects onto space. Bausinger wrote a great deal about that misguided effort in the 1970s, as he dug into the region’s many linguistic variations in a series of dialect studies. Some of that work involved intense analyses of granular variations across interconnected villages, while some of what he did in the 1980s underscored how dialects like Allemanisch and Schwäbisch, which linguists tended to group together before the nineteenth century, became separated as literary scholars and scientists worked together with politicians to legitimize Württemberg’s emergence as a kingdom and distinguish it from Baden. Their postwar counterparts also quickly tapped into those invented traditions while fashioning a prehistory for Baden-Württemberg, tying Allemanisch to Baden and Schwäbisch to Württemberg in ways that encouraged people to use the linguistic and political designations interchangeably.[10]

Political efforts to naturalize these nations not only obscured the reality that the dialects in question, like all languages, exist independently of the people using them but also the fact that terms like Swabian or Saxon refer to languages that have shifted and evolved over time.[11] Consequently, attempts to match cultures and dialects onto places and spaces have always been highly problematic, even when it came to codifying and regulating groupings such as Swiss-Germans, an effort that gained considerable support in the 1930s in response to the homogenizing power of linguistic standardization (and fascism) from the north. Bausinger refers to that effort as an act of “spiritual national defense” [geistigen Landesverteidigung] but that made the homogenizing efforts behind the codification of Swiss German no less problematic.[12]

The challenge of trying to contain language within space and tie it to place becomes easier to understand when we accept that the mobility of people speaking these dialects and languages was far greater even in the early modern period than historians used to assume. For someone like Bausinger, who witnessed the postwar flood of German speakers from all over central and eastern Europe into what became the state of Baden-Württemberg, it was easy to imagine encounters among different kinds of German speakers in the previous centuries. In the past, as we now know, some twenty-five to thirty percent of the people in central Europe were on the move. As Bausinger began his career, the American and French zones of occupation were inhabited by large numbers of German speakers who were from someplace else—at least ten percent of the population in Baden and over twenty percent in Württemberg. He studied their interactions as an ethnologist would, noting not only the divisions among people from different places, such as the Saxons, who were ostensibly represented by their Heimat organizations, but also the dexterity with which people moved in these multilingual and multicultural realms.[13] He was particularly impressed by the children who could code-switch, linguistically and culturally, so consciously and quickly. Initially, many European ethnologists went into these refugee neighborhoods to study remnants of language islands they had once studied further East, far along the Danube. After a short period of time, however, most moved away from looking for information about that past and tracking acculturation. They began instead to focus on process—how people adapted and moved within these multicultural and multilingual German worlds.[14] Consequently, ethnologists have often been more attuned to the complex interconnections animating this region’s histories than its historians.

Transregional Bregenz

Despite the singularity of that postwar moment, there was much about what Bausinger and his counterparts observed in southern Germany that was not new. Nor was it limited to the German side of the southern German border.[15] The multiplicity of cultures and languages, the code-switching, and the many ways in which border traffic had long been the norm, for example, were all at the heart of the displays in the Vorarlberg Museum in Bregenz, when it reopened in a new building in 2013. Bregenz, incidentally, is no further from Obergünzburg than is Munich. But it is in another country.

Rather than sitting at the center of the Bavarian state like Munich, Bregenz is located on the edge of the Bodensee, where Austria, Germany, Lichtenstein, and Switzerland come together.

Yet even as it balances on the periphery of those nation-states, quite literally on the tail-end of Austria, it is, and has long been, its own center. It also has been attracting swarms of visitors for over a century. It was, in fact, the ships on the Bodensee that one can see from Bregenz, which made the young Karl Nauer from Obergünzburg want to go to sea in the first place.

The striking thing about the Vorarlberg Museum is that it is no longer a Landesmuseum (state museum) or at least not one that narrates the history of a political region by focusing on the state, its rulers, and its people. Rather, since it was recast in 2013, the museum began offering visitors windows into the histories of the peoples who have lived in the land situated between the massive Arlberg (mountain) and the Bodensee, including an exhibit on “the making of Vorarlberg,” which directly engaged its cultural construction.[16]

In fact, one of its most stunning displays is a panoramic window (Fig. 6) that looks out at the lake and allows one to see the confluence of Austria, Germany, and Switzerland (as well as Lichtenstein with a little imagination). It also allows us to gaze across waters that have drawn people together from a wide variety of places for as long as people have been in what we now call Europe.

The fluid histories narrated in this institution are of people who were both tied to localities and frequently on the move. For centuries, they have had connections to other people in the many and varied locations surrounding the lake, in part because many of the people born in Vorarlberg went to live and work in those lands. They also went much further afield. Seasonal labor migration in the Alpine region, in fact, is well documented by the end of the sixteenth century. Explicit numbers are impossible to obtain because none of this labor migration was organized or regulated by states; only the towns they left took note of their absences.

Yet we know that several thousand children, the so-called Schwabenkinder, journeyed north from Vorarlberg, Tirol, and Switzerland every year, reaching a high point in the middle of the nineteenth century. Eventually, those child laborers were organized by adults into groups, some of whom stayed with them in Oberschwaben during the summers, while other adults traveled back home and then returned to get them at the end of the growing season.[17] Once obscured in the history, those movements gained much scholarly and local attention in the 1970s, and we have since learned a great deal about them. According to Loretta Seglias, for example, these child laborers crossed the borders of Liechtenstein, Vorarlberg, Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden with only their local identity papers. They did not use passports, because the states did not require them; those states had no desire to make this seasonal mobility more difficult. There was a clear need for the labor in the north, and the children generally returned south well-fed, better dressed, and with a bit of desperately needed money.[18] Everyone regarded it as mutually beneficial, at least economically. What it also meant, of course, is that across generations, a great many people in this region grew up with the experience of mobility across a variety of borders and living among people different from themselves, adding to their quiver of linguistic and cultural skills.

While this seasonal migration from the mountain valleys of Switzerland has seen much less scholarly attention than overseas migration, there is no question that the two were interrelated. Recent work on central European labor migrations has shown this to be true more generally.[19] To a large degree, that is because after the 1850s, eastern Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and Vorarlberg shared “a stunning economic dynamic” driven largely by textile industries. This caused emigration into this region to surpass its out-migration by the 1880s and 1890s (depending on precise locations). During the first decades of the twentieth century, in fact, Vorarlberg witnessed the most intensive industrialization of any region in the Austrian-Hungarian Empire.[20]

If, by 1910, as Andreas Weigel estimates, some 6,000 men and women left Vorarlberg to work seasonally in Switzerland, while many others went to France, Luxemburg, and the Netherlands,[21] even more people wandered into Vorarlberg to join its industrial labor forces. By 1900, almost twenty percent of the people living in Vorarlberg had not been born there.[22] Many came from the Tirol, even more from Italy, and quite a significant number were from Hungary. In other words, locals in Bregenz and many surrounding valleys not only engaged in transient labor, they also lived with it at home. Thus, living among highly mobile people and cultural, linguistic, and confessional difference was hardly limited to the families of the Schwabenkinder. It was widespread across a region that extended far beyond this tip of Austria.[23]

If the political borders around the Bodensee (which to this day remain imprecise) sometimes delimited people’s mobility, especially during times of crises following the rise of the passport revolution after WWI, they more often generated economic possibilities. As a result, a wide variety of cross border collaborations persisted right through the many economic and political crises of the twentieth century. Indeed, from the point of view of locals, the region’s political borders were no more “set in stone”in the modern era than during the era of bishoprics and other early modern states. As the editors of a fantastic recent volume on the topic remind us, both butchers in the Swiss town of St. Gallen and herders from Austrian Montafon (renowned today for hiking and skiing) took their cows to winter in Appenzeller as part of a labor division and alpine, cross-border economic collaboration that characterized the entire region. For generations, people on all sides of the political borders worked together to manage landscapes and care for the cows, and that persisted over centuries of regime changes, border crossings, and regional and global conflicts right through the modern era.[24]

Smuggling existed as well, and so too did economies built around it, which also crisscrossed the borders. Again, that is hardly unique to this part of Europe. It is characteristic of many border regions, and there is great work, for example, on smuggling in the Bohemian-Saxon borderlands.[25] Here too, one also sees a mix of languages and cultures crossing the southern borders, but because of Swiss neutrality in the wars, and especially during the era of National Socialism, the character of the border with Austria does change for some time. If, for example, labor migration from Switzerland into Austria persisted during WWII, it was fraught by new implications of young, Swiss labor interacting with Nazis. And while there were still smugglers working that border, they were sometimes engaged in moving people across a space that became fortified, policed, and staffed with unprecedented numbers of officials, making their activities far more dangerous. Moreover, there was concern among Austrian and Swiss officials with the mass flight of refugees before, during, and after the war. The tales of those who did and did not help them have not only become part of local lore but also feed the burgeoning tourism in places such as Samnaun, where smugglers had always been regarded as local heroes, and the local economy long benefitted from special arrangements for customs duties, which, like many things, were reinstated again not long after the war.[26]

Transnational Unteruhldingen

Dialing out the timeline to a much longer durée is just as important as focusing in on specific historical situations. Archeological finds, such as the abundance of old coins in the earth, have long made clear to inhabitants of this region that the space between the Alps and the Rhine was a transit area with great economic importance for as far back as we have records.[27] The open-air Pile Dwelling Museum [Pfahlbauten Museum] in Unteruhldingen, on the northwestern shore of the Bodensee, also makes that clear. It too is only about 100 km from Obergünzburg, at least as birds fly. No roads are that direct. The first time I visited, the Museum Director, Gunter Schöbel, immediately took me to the nearby Basilika Birnau.Its baroque architecture is impressive, but so too are its unparalleled views of the region on the bluff above the shore. Looking out over the lake, one sees the Alps to the south while understanding that the Danube flows to the north. This, he explained, is where copper came from the first and tin from the second to produce the bronze that shaped the age in which the pile lake dwellings at the center of his museum were first fashioned. The Bodensee has remained a crossroad ever since—as the Romans came and went from Konstanz on the opposite shore, as others came and went, and as, through those transitions, the fishing economies remained, and the trade networks persisted, expanded, and thickened.

Water unites people, and the view from Birnau helps to explain why, as one of the directors of the Landesmuseum in Stuttgart remarked to me, the divisions inscribed across the region by modern political borders are “completely absurd.” From Birnau, as much as from the panorama window in the Vorarlberg Museum, the Bodensee fails to mark the surrounding countries’ borders. Rather, the lake shores circumscribe a center, and its peripheries extend far and wide to include many cities in those surrounding nation-states, the fractured landscapes Bausinger studied so completely, as well as the Alps themselves.

The Pfahlbauten Museum in Unteruhldingen, like the South Seas Museum in Obergünzburg, is also frequently filled with children. Yet only a small percentage of those children and their families are locals. The over 300,000 visitors who arrive every year come from all over the region and even further abroad. That is far more visitors than the museum in Obergünzburg, and considerably more than most museums in Germany. One of the draws is the kind of practical archeology underway at the museum, where objects do many things in the hands of visitors that they cannot do in other such institutions, like cut, scrape, and allow visitors to feel the movements that created bronze-age things. Gunter Schöbel, who is a proponent of practical archeology for both pedagogical and scholarly reasons, enjoys teaching people how to use the objects in their collections, and through that process, to better understand their importance for the people who fashioned them. It gives them, he thinks, a connection to other people who were once there.

Understanding the implications of that statement requires recognizing that the Pfahlbauten Museum in Unteruhldingen has been around for over a century, and it is only one of many similar kinds of museums across the region. The history they animate in their displays existed across the subalpine region running from Slovenia to France. That history began gaining a great deal of scientific attention after the first settlement sites were identified near Zurich in the middle of the nineteenth century, leading to a quick succession of similar discoveries in other lakes and wetlands over the last 150 years. Today there are, in fact, over 111 archeological digs and exhibits that are included in a widespread UNESCO world heritage serial site. That designation not only recognizes the linked histories across this vast region; it also serves to tie together the people within it by jointly linking them to that part of world history and by allowing each of the individual sites, regardless of how provincial they might be, to claim global importance.

It is worth contemplating what UNESCO’s international designation does for the local communities that receive it, leverage it, and develop it. We might ponder how provincial they are, given that they bring global distinction and recognition of world heritage to the metropoles of the various political states that demand taxes from them. In addition, we should take seriously the vast heritage network they support, as well as the broader network of cultural institutions spanning the region in which they are included. After all, that constitutes an impressive array of historical markers and public institutions that, much like the people in the region, have long been intimately entangled without a designated center. They have thrived that way for generations.

There is even an historical association devoted to the region around the Bodensee that began publishing a scientific journal in 1868 and continues to publish today.[28] From the outset, it included members, subscribers, and supporters from all the political states in the region. As those states shifted and changed over the last 155 years, they made the point of consistently publishing the lists of their members and officers, who continued to come from the surrounding lands and actively promoted their institution and its publication as transregional and, as we would say today, transnational.

That is an impressive articulation of historical consciousness as well as a politics of inclusion that draws on both a chronological depth and a spatial breadth that purposefully eschews the traditions invented to support the various states in the region. In fact, it upends those traditions. Among other things, pile lake dwellings from the region have been featured in the pages of this journal across the entire chronology, presenting its readers with the most current research. It continued to do that even as the research undercut the initial attempts by nation-states and their supporters, beginning with the first lakeside investigations in Switzerland, to harness the locations, objects, and literature to support politically driven interpretations that might legitimate claims to national particularities.[29] That has included the revelation that these sites were not permanent communities. Rather, the villages were built, rebuilt, abandoned, and reconstructed by collections of people who were on the move, adapting to shifting environments, and connected to each other and to people far beyond through routes of migration and trade.

We could, if I dared to subject you to more revelations from Hermann Bausinger, draw that insight forward in time across the periodization of ancient, early modern, and modern European history to discuss the many ways in which the diverse landscape around the Bodensee, as he put it, continued to be regarded as a unity through all epochs and across their varied political regimes.[30] Most importantly, from his perspective, are the ways in which that has left us, those who came before us, and those who will follow us, with a landscape of palimpsests, filled with bright and dull areas, places where older worlds are occluded and where some or many shine through.

Global Blaubeuren

In the Prehistorical Museum in Blaubeuren however, the history goes even deeper, giving this tiny town a unique place in world history. It is one of five museums in Baden-Württemberg that contain ice-age objects from nearby caves in the Swabian Alb, which include the world’s oldest three-dimensional carved objects and musical instruments (ca. 40,000 years).Those digs, and thus the surrounding landscapes, also have UNESCO world heritage status, even if the objects that archeologists have removed from them do not. Nevertheless, those five museums in Blaubeuren, Stuttgart, Tübingen, Ulm, and the recently closed and now in limbo Vogelherd archeology park are tied into the many other archeological museums in the region, including those that offer renditions of pile lake dwellings.[31] Some do a bit of both. They also all inform the same questions about global human heritage, local particularities, the cultural and political resonance of these local and universally human histories, and much more.

The narratives in these municipal archeological institutions vary, depending on how the curators deploy the objects, or fail to deploy them. Thinking about what all these objects do and cannot do offers another window into the chaotic cultural multiplicity of the region. It also underscores the lack of a clear cultural center even in the state of Baden-Württemberg, which, like Bavaria, has a political capital (Stuttgart) and an extensive bureaucracy dedicated to managing its cultural affairs. Yet neither the state politicians nor the bureaucracy can control them: there are too many joint projects, producers, and actors animating these museums, supporting them, encouraging further collecting through excavations, and further engagement with publics. Those publics matter, especially because they are not limited to the people living in the individual locations. If the museum in Unteruhldingen draws in over 300,000 people a year, there are millions visiting its counterparts throughout the region. Some are local, and many of those were likely prepared for their region’s particular connection to ancient history by reading the naturalist David Friedrich Weinland’s 1878 novel Rulaman, a work of classic youth literature focused on the Alb during and after the Ice Age, which was every bit as popular in the region as Karl May over the twentieth century.

Yet, in Blaubeuren, it is impossible to overlook the cosmopolitan or international character of the people animating this town of ca. 12,000 inhabitants, taking in the Blautopf (deep natural spring) and the Abbey along with the museum. They come from all over the world to this provincial center of world history. The town council understands that, and it built upon that draw for economic gain. So too does the region. They are also curating the surrounding landscapes, fashioning ice age parks, reserves, and throughfares, where one can quite literally cycle or walk along newly paved paths through the palimpsests or layered histories in the region and view those bits that local ‘stake holders’ have polished up for the local, regional, national, and international publics—recasting their local landscapes as world heritage and helping visitors to see a past, our past, in their present. Tourists still come to see the Blautopf, as they have for generations, but they now get much more than that.

Over the last half-century, scholars have filled rooms with books on this heritage industry and its impact on localities such as Blaubeuren. Some of that scholarship is part of the equally massive studies of tourism.[32] The work in both areas has demonstrated that heritage and tourism industries have played critical roles in shaping notions of belonging in this region during the modern era. In some ways, tourism is the older story; yet heritage (or public history) was long part of it as well, even before the heritage industry became increasingly regulated and global during the postwar era. People such as Bausinger recognized that already in the early postwar era, and he and his colleagues across the region, like Walker Leimgruber in Basel, spent entire careers analyzing people’s actions within these shifting structures and unpacking the implications.

Postcolonial Basel

It is worth ending this essay with a few final reflections on tourism and heritage, because they will help to further develop some of the points I have been making about mobility and multiplicities in the region. They will also support my claim that the region has long been a center of Europe, containing many cosmopolitan centers in places that were arguably even more provincial than Blaubeuren (which is, incidentally, also located only about 100 km from Obergünzburg).

The thing about tourism in this region, is that it was fashioning cosmopolitan centers out of provincial places long before that happened in Blaubeuren. Adam Rosenbaum has made this point in his work on spa towns in the Frankenjura, or the Franconian Schweiz, that region lying roughly between Nuremberg and Regensburg in Bavaria, where already in the nineteenth century visitors came from far and wide, speaking many languages, and creating cosmopolitan, transcultural spaces. The tourist history of Bad Reichenhall, for example, nestled on the Austrian border, demonstrates how that also flowed easily across the border, as regional attractions trumped national division in advertising campaigns, infrastructure efforts, and tourists’ activities.[33] Its history fits into the history of the greater area around Salzburg, which also has been a tourist center for the last two centuries, and which became increasingly and purposefully tied into the rest of the subalpine and alpine regions by interregional railroads during the second half of the nineteenth century. Those networks have only expanded and thickened since then, as the summertime tourism that brought hikers and climbers into sublime landscapes was doubled by skiing and other modern winter sports in the early twentieth century and especially in the postwar era.[34] Today, according to Werner Bätzing,the Alps are “one of the largest and most important tourist regions on earth.[35] Still, those activities do not blanket every corner of the region, and so the impact is not uniform. As we would expect, they are concentrated in some alpine settings more than others, and within those areas, the density is in individual locations. Initially, the vast majority of those were in Switzerland. There, modern medicine and railroads transformed villages like Davos into spa towns that eclipsed places such as Bad Reichenhall as cosmopolitan nodal points in a network of transnational elites.[36]

The larger story, however, as the work on the Austrian and German Alpine Associations makes clear, is that the creation of this tourism and the infrastructure of guides, huts, hotels, railroads, restaurants, roads, spas, signs, ski lifts, and thousands of kilometers of trails and stairs was a joint project in which locals in villages learned to work with people from all over German-speaking central Europe and to initiate projects to refashion and commodify this space.[37] Local, regional, and national governments within the region acted similarly, as they worked with this transnational movement to regulate the space, the labor, and the science behind the region’s preservation and transformation—which ranged from cartography, meteorology, and studies of glaciers to research into dialects and other forms of Volkskunde.

If the swath of the Alps that lies within the border of the German nation-state is only 20-30 km wide, the Eastern Alps are frequently referred to as the German Alps. In part, that is due to these associations, which grew so quickly across the turn of the century after fusing together in 1874. The Deutscher und Österreichischer Alpenverein (DAV) not only became the largest Alpine association in the Eastern Alps but also the world, as its initial count of 4,844 members grew to over 200,000 by 1925, with the vast majority stemming from someplace north of the Austrian-German border, and all of them consuming and circulating its maps, essays, books, art, expedition reports, and public lectures about the region.[38] Consequently, as Ben Anderson makes clear through his local studies: “nationalism provides only a limited perspective from which to assess the motives and objectives of people living in the Alps and their relationship to the interventionist tourism typified by the Alpenverein.” Tiroleans sought out investments and visitors, guides became powerful labor lobbies across the transnational region, and Austrians, Italians, Germans, and their respective histories swirled together.[39]

Not surprisingly, the Annales ethnologist and historian Lucie Varga anticipated all that with her studies of local communities in Vorarlberg undergoing transitions during the 1930s as urban culture rolled into the valleys; the people there started following what was happening in cities, giving up traditions, and living through situations in which locals no longer wore folk costumes or Trachten, but many tourists did.[40] Hometowns where people still struggled with nature to survive became part of a sprawling Erlebnisraum in which ethnologists, collectors, and tourists eagerly commodified folk arts and crafts as they did in Amazonia, on Pacific Islands, or North American national parks, reserves, and reservations. In the Alps, as in those other places, ethnologists found artisans producing ‘traditional things’ for urban collectors and visiting consumers, while in some cases other ethnologists, as Konrad Kuhn has shown, continued to use those products as sources for systematic descriptions of vanishing or transforming cultures.[41]

Varga, however, did not anticipate the many curious juxtapositions that the heritage culture has created as it became truly global in a postcolonial world. But many others, such as Anna Schmid, the director of the Museum of Cultures in Basel [Museum der Kulturen], have been thinking about the implications of non-Europeans eagerly consuming the Ur-kultur in central Europe, inverting many tropes in postcolonial studies.[42]

Given that Heidi was one of the most successful children’s books in world history, translated into some fifty languages since it first appeared in 1880, selling about fifty million copies worldwide, and recirculating in countless comics, films, musicals, and television shows and series, Walter Leimgruber estimates that ninety-five percent of the tourists who visit the region as part of those global flows know the story.People in Japan, he notes, love this anti-capitalist cipher for a lost paradise much more than the inhabitants of the “rich, Protestant, wine growing region” of Maienfelder, where she supposedly lived. There, tourists flock to see the landscapes they have long imagined, but as Varga also noted in Vorarlberg in the 1930s, many of the people they encounter mostly tolerate them while remaining focused on working to survive.[43] This adds, I think, a poignant twist to the classical question “Whose Heritage?” posed some twenty years ago by Stuart Hall about national heritage in a postcolonial world, before that heritage was globalized as it is today.[44] At the same time, I also think it offers us a much different way of globalizing European and German history than we generally do while considering the implications of provincializing or decolonizing those histories, and it is one that I believe is in the process of upending the historiography.

[1] H. Glenn Penny, German History Unbound: 1750s to the Present. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

[2] André Holenstein, Mitten in Europa: Verflechtung und Abgrenzung in der Schweizer Geschichte (Baden, 2014).

[3] Kathleen Conzen, “Phantom Landscapes of Colonization: Germans in the Making of a Pluralist America,” in Frank Trommler and Elliott Shore eds., The German-American Encounter: Conflict and Cooperation between Two Cultures, 1800–2000 (New York, 2001), 7–21.

[4] Reinhard Baumann, ‘Dreigeteiltes Allgäu’—die Integration einer historisch gewachsenen Landschaft in den bayerischen, österreichischen und württembergischen modernen Staat,” in Carl A. Hoffmann and Rolf Kießling eds. Die Integration in den modernen Staat: Ostschwaben, Oberschwaben und Vorarlberg im 19. Jahrhundert (Konstanz: UVK, 2007), 157-79, here 178.

[5] Bausinger came to ethnology through his studies of German literature, writing extensively on dialect, migration, tourism, and invented traditions, long before that idea became commonplace in scholarly literature. He grew to be a leader in his field of Volkskunde by the 1960s, which he helped to recast as Empirische Kultur Wissenschaft, while shaping generations of ethnologists who studied with and around him at Tübingen University’s Ludwig Uhland Institute.

[6] Werner Richner and Hermann Bausinger, Baden-Württemberg: Landschaft und Kultur im Südwesten (Karlsruhe: G. Braun, 1994), 33-34.

[7] Ibid., 34.

[8] Ibid., 37. See also: Roland Scherer, “Eine Grenzregion als Wachstumsregion: was man von den Governance-Strukturen der Bodenseeregion lernen kann,” in Martin Heintel, Robert Musil, Norbert Weixlbaumer eds. Grenzen. Theoretische, konzeptionelle und praxisbezogene Fragestellungen zu Grenzen und deren Überschreitungen (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2017), 237-253.

[9] Ibid., 59. See also: Dieter Langewiesche, Vom vielstaatlichen Reich zum föderativen Bundesstaat. Eine andere deutsche Geschichte (Stuttgart: Kröner Verlag, 2022).

[10] Hermann Bausinger, Berühmte und Obskure: Schwäbisch-alemannische Profile (Tübingen: Klöpfer und Meyer, 2007), 20-26.

[11] Hermann Bausinger, Dialekte, Sprachbarrieren, Sondersprachen (Frankfurt: Fischer, 1972).

[12] Ibid., 33.

[13] Hermann Bausinger, Volkskunde: Von der Altertumsforschung zur Kultureanalyse (Berlin: Carl Habel Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1971), 146-57.

[14] Hermann Bausinger, “Das Problem der Flüchtlinge und Vertriebenen in den Forschungen zur Kultur den unteren Schichten,” in Rainer Schulze et. al. Flüchtlinge und Vertriebene in der westdeutschen Nachkriegsgeschichte: Bilanzierung der Forschung und Perspektiven für den künftige Forschungsarbe (Hildesheim: A. Lax, 1987): 180-195.

[15] For similar reflections on Switzerland see: Walter Leimgruber, “Assimilation, Integration, Kohäsion, Partizipation,” in Reinhard Johler and Jan Lange eds. Konfliktfeld Fluchtmigration: Historische und ethnographische Perspektiven (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2019), 65-80. He too notes that in Switzerland as well the current population is about 25% foreign/immigrants, while about ¾ of Swiss citizens currently living abroad have multiple passports. More than 1/3 of Swiss citizens have some sort of migrant background, with one parent coming from abroad, and fully 40% are binational, and none of this is as new as many might claim. In 1914, 15% of the population consisted of immigrants, in Lugano 30.8%; in Basel, 40.4 %; and the numbers would be bigger except there was a quick process for gaining citizenship—just 2 years.

[16] Markus Barnay and Andreas Rudiger eds., Vorarlberg: Ein Making-of in 50 Szenen. Objekte/Geschichte/Ausstellungspraxis (Bielefeld: Transkript, 2022). This exhibit is currently being revised.

[17] Michael Kasper und Christof Thöny, “Schwabenkinder und andere Formen der alpinen Arbeitsmigration – eine Spurensuche zwischen gestern und heute” Zeitschrift für Agrargeschichte und Agrarsoziologie 68 no. 2 (2020): 81-96.

[18] Loretta Seglias, Die Schwabengänger aus Graubünden: Saisonale Kinderemigration nach Oberschwaben (Chur: Kommissionsverlag Desertina, 2004), 20, 51-53.

[19] Annemarie Steidl, On Many Routes: Internal, European, and Transatlantic Migration in the Late Habsburg Empire (Purdue University Press, 2020).

[20] Peter Melichar, Andreas Rudiger, Gerhard Wanner eds. Wanderungen. Migration in Vorarlberg, Liechtenstein und in der Ostschweiz zwischen 1700 und 2000 (Wien, 2016), 16-17.

[21] Andreas Weigel, “Migration, Industrialisierung, Weltkrieg: Die Faktoren der demographischen Transition in Vorarlberg,” in Melichar et. al. Wanderungen, 23-53, here 41-42.

[22] Gerhard Wanner, „Migration in Vorarlberg um 1900: Ethnische Gruppen, soziale Spannungen?“ in Melichar et. al. Wanderungen, 131.

[23] Ursus Brunold ed., Gewerbliche Migration im Alpenraum. La Migrazione Artigianale Nelle Alpi. (Bozen: Verlagsanstalt Athesia, 1994).

[24] Nicole Stradelmann, Martina Sochin D’Elia, and Peter Melichar, Hüben & Drüben: Grenzüberschreitende Wirtschaft im mittleren Alpenraum (Innsbruck: Universitätsverlag Wagner, 2020), 8-11.

[25] Caitlin Murdock, Changing Places: Society, Culture, and Territory in the Saxon-Bohemian Borderlands, 1870-1946 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010).

[26] See for example Christian Ruch, “’Zwischen Stühle und Bänke geraten’. Samnaun zwischen 1938 and 1945,” 103-119; and Michael Kasper, „Illegale Grenzübertritte im Gebirge. Flucht und Schmuggel zwischen Vorarlberg und Graubünden vom 18. bis ins 20. Jahrhundert,” 121-143, in Stradelmann et. al. Hüben & Drüben.

[27] Ibid., 11.

[28] Schriften des Vereins für Geschichte des Bodensee’s und seiner Umgebung.

[29] Marc-Antoine Kaeser, “Archaeology and the Identity Discourse: Universalism versus Nationalism. Lake-dwelling Studies in 19th Century Switzerland,” in A History of Central European Archeology: Theory, Methods, and Politics, Alexander Gramsch and Ulrike Sommer eds., (Budapest: Archaeolingua Alapítvány, 2011), 143-160; Francesco Menotti, Living on the Lake in Prehistoric Europe: 150 Years of Lake-Dwelling Research (New York: Routledge, 2004).

[30] Hermann Bausinger, Der herbe Charme des Landes: Gedanken über Baden-Württemberg (Tübingen: Klöpfer & Meyer, 2006), 15.

[31] Joachim Striebel, “Eiszeit: Heidenhiem tritt aus,” Südwest Presse Ulm, 19 July 2023, 35-37.

[32] E.g. Sharon Macdonald ed., Doing Diversity in Museums and Heritage. A Berlin Ethnography (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2023).

[33] Adam T. Rosenbaum, Bavarian Tourism and the Modern World, 1800-1950 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

[34] Bernhard Tschofen, Berg, Kultur, Moderne: Volkskundliches aus den Alpen Sonderzahl (Wien: Sonderzahl Verlagsgesellschaft, 1999); Andrew Denning, Skiing into Modernity: A Cultural and Environmental History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015).

[35] Kurt Luger and Franz Rest eds., Der Alpentourismus: Entwicklungspotenziale im Spannungsfeld von Kultur, Ökonomie und Ökologie (Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 2002), 176.

[36] Alison Frank, “The Air Cure Town: Commodifying Mountain Air in Alpine Central Europe,” Central European History 45 (2012), 185–207.

[37] Ben Anderson, “Alpine Agency: Locals, Mountaineers and Tourism in the Eastern Alps, c. 1860–1914,” Rural History 27, no. 1 (2016): 61–78.

[38] Corinna Peniston-Bird, Thomas Rohkrämer, and Felix Robin Schulz, “Glorified, Contested and Mobilized: The Alps in the “Deutscher und Österreichischer Alpenverein” from the 1860s to 1933,” Austrian Studies, 18, Austria and the Alps (2010): 141-158, here 147. See also Anneliese Gidl, Alpenverein: Die Städter entdecken die Alpen. (Wien: Böhlau, 2008).

[39] Anderson, “Alpine Agency,” 63. Laurence Cole and Hans Heiss, “’Unity Versus Difference’: The Politics of Region-building and National Identities in Tyrol, 1830-67,” inCole ed., Different Paths to the Nation: Regional and National Identities in Central Europe and Italy, 1830-1870 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 37-59.

[40] Lucie Varga, “Ein Tal in Vorarlberg—zwischen Vorgestern und Heute,” 1936, 146-69 in Peter Schöttler ed., Lucie Varga Zeitenwende: mentalitätshistorische Studien, 1936-1939 (Suhrkamp, 1991). See also: Werner Bätzing, “Der Stellenwert des Tourismus in den Alpen und seine Bedeutung für eine nachhaltige Entwicklung des Alpenraumes,” in Luger and Franz Rest eds., Der Alpentourismus, 175-96. For a classic history of mobilities and melding see: John W. Cole and Eric R. Wolf, The Hidden Frontier: Ecology and Ethnicity in an Alpine Valley (New York: Academic Press, 1974).

[41] On the dialogic of production see: Hermann Bausinger, Volkskunde: Von der Altertumsforschung zur Kultureanalyse (Berlin: Carl Habel Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1971), 160-66 and Reinhard Johler, Die Formierung eines Brauches: Der Funken- und Holepfannsontag. Studien aus Vorarlberg, Liechtenstein, Tirol, Südtirol und dem Trentino. (Vienna: Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, 2000); for the systematics despite that dialogic see: Konrad J. Kuhn, “Markt-Masken. Dinge zwischen materieller Produktion und ökonomischen Marktbedingungen,” in Karl Braun, Claus-Marco Dietrich, and Angela Treiber eds., Materialisierung von Kultur. Diskurse – Dinge – Praktiken (Würzburg 2015), 155-164; for more on the locality and belonging as process: Beate Binder, “Beheimatung statt Heimat: Translokale Perspektiven auf Raume der Zugehorigkeit,” Zwischen Emotion und Kalkül: ‘Heimat’ als Argument im Prozess der Moderne (2010): 189-204; also Binder, “Heimat als Begriff der Gegenwartsanalyse? Gefühle der Zugehörigkeit und soziale lmaginationen in der Auseinandersetzung um Einwanderung,” Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 104 (2008): 1-17; and for the Alps in particular: Walter Leimgruber, “Alpine Kultur: Welche Kultur fiir welchen Raum?” in Beate Binder, Silke Gottsch, Wolfgang Kaschuba, and Konrad Vanja eds., Ort. Arbeit. Körper. Ethnografie Europaischer Modernen (Münster: Waxman, 2005), 147-55.

[42] Patricia Purtschert and Harald Fischer-Tiné eds., Colonial Switzerland: Rethinking Colonialism from the Margins, (New York: Palgrave, 2015).

[43] Walter Leimgruber, „Heidi und Tell: Schweizer Mythen in regionaler, nationaler und globaler Perspektive,” in Karin Hanika and Bernd Wagner eds., Kulturelle Globalisierung und regionale Identität: Beiträge zum kulturpolitischen Diskurs (Bonn: Klartext, 2004), 32-44.

[44] Stuart Hall, “Whose Heritage? Unsettling ‘The Heritage’, Reimagining the Post-Nation” Third Text, 49 (1999): 3-13.