Remembering and Remapping Breslaff: Resurfacing German and Queer Topographies in Contemporary Polish Literature

TRANSIT vol. 14, no. 1

Alicja Kowalska

Abstract

This article focuses on the role of contemporary Polish literature in bringing back that which has been repressed under communism: the Germanness of the so-called “regained territories”, i.e. territories that became Polish due to the changes of national borders after the Second World War, as well as the marginalized queer life. I discuss two novels that feature the city of Wrocław, formerly German Breslau: Marek Krajewski’s Death in Breslau (1999) and Michał Witkowski’s Lovetown (2004). My analysis draws parallels between bringing back the German past of the city and remembering queer life during communism in fiction. Marek Krajewski situates the plot of his highly popular crime novel in Breslau in the 1930s. By doing so, he fictionally recreates the former German city which allows the reader to rediscover its past and foreign layer. Michał Witkowski’s prose performs a similar task by describing parts of the city that were central to queer culture but hidden from the experience of the “general public” under communism. I argue that remembering takes effect through remapping and that this literary remapping destabilizes the narrative about Polish culture as a homogeneous block of monolingualism, Catholicism, and heteronormativity. Furthermore, the fictional topographies of the German Breslau and the queer Wrocław alter the existing geospace by overlaying a suppressed otherness onto it.

Keywords: memory, mapping, contemporary Polish literature, “regained territories”, topography, identity

Introduction

In The Dissection of the Psychical Personality, Sigmund Freud writes that “impressions…which have been sunk into the id by repression, are virtually immortal; after the passage of decades, they behave as though they had just occurred” (74).[1] Repressed memories, in other words, are destined to return; they are, according to Freud, of an indestructible nature. When applying Freud’s insight to collective repression and memory, one often finds literature to be the medium most attuned to the “forgotten,” to that which awaits resurfacing. This article argues that, due to its unlimited potential of imagining and reimaging the past, contemporary Polish literature plays an important role in Polish remembrance culture, especially when it comes to bringing back memories that, after the Second World War, were repressed by Polish communist authorities due to nation-building strategies and censorship. Among others, these memories include recalling the Germanness of the so-called “regained territories,” i.e. territories that became Polish due to the changes of national borders after the Second World War, as well as the memory of marginalized homosexuality during communism. Furthermore, remembering in and through fiction points to the difficulty of remembering within an official and national setting that which has been repressed under communism.

After the Second World War and due to agreements resulting from talks at the Teheran conference in 1943 and the Potsdam conference in 1945 between the Allied forces and the Soviet Union Germany’s former Eastern borderlands became Poland’s Western borderlands.[2] This border shift profoundly affected the Lower Silesian city of Breslau, which became Polish Wrocław. Having to absorb large swaths of foreign territory into a newly created Polish state, the Polish communist government used propaganda to suppress the German past of the city of Breslau as well as the rest of the so-called “regained territories.”[3] The communist government’s efforts were so successful that the consequences of suppressing the city’s past lingered well past the fall of communism. In the mid-1990s, Andrzej Zawada, a Polonist from Wrocław, named the city “Bresław” (a combination of Breslau and Wrocław) to capture “his hometown’s neurosis” (Thum 382). In an essay entitled Bresław, he described Wrocław as “a city with an amputated memory.” He found himself “unsettled and irritated by its crippledness. It was impossible to walk down the streets of Wrocław without thinking about it …Wroclaw’s past was hidden the way a so-called ‘good home’ conceals the embarrassing secret of someone’s illegitimate birth” (qtd. in Thum 382). Considering 1989 as a turning point for remembering the German past of the city, Gregor Thum states that after all, “suppressing this foreignness was a hopeless enterprise” (383). He points to the split between the public and the private sphere concerning memory: “However much the German past was avoided in public and concealed under the propagandistic myth of eternal Polishness, it remained present in the private sphere” (383).[4] Another culture with seemingly no history or presence in the city concerns marginalized homosexual men during communism. In his study, Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland: Cross-Border Flows in Gay and Lesbian Magazines, Lukasz Szulc pinpoints the “dehistoricization of homosexuality” in Central Eastern Europe as the main basis for half-truths and myths around LGBT issues in that region (Szulc 5).[5] His study of annual reports by the Homosexual Initiative Vienna (HOSI) aims at filling some of the blank pages of the history of homosexuality within the Eastern Bloc.[6] Furthermore, similar to the Germanness of the city’s past, homosexuality[7]under communism was relegated to the private sphere and rendered invisible in the city of Wroclaw as well as in the public discourse at large of the People’s Republic of Poland.[8]

In this article, I focus on two books in which the formerly German city is used as a setting: Marek Krajewski’s Death in Breslau (1999) and Michał Witkowski’s Lovetown (2004). The crime novel Death in Breslau takes place in the 1930s in German Breslau, reestablishing the German map of the city and bringing its German past to life. Witkowski’s Lovetown is a fictionalized oral history that addresses queer life in the city of Wrocław during communism, featuring the voices of several homosexual men who tell stories about their life, thereby bringing another repressed form of life to the surface and onto the map of the city. Reading Death in Breslau and Lovetown together reveals how contemporary Polish literature challenges the narrative about Polish culture as a homogeneous block of monolingualism, Catholicism, and heteronormativity. By exploring the links between identity, memory, and topography both literary texts bring to the fore that which has been suppressed under communism. They thereby question the cultural homogeneity that has been put at the core of national identity as a result of border changes and nation building strategies under state socialism.

Borders and delineations play a crucial role in defining and structuring a national identity, but they can also be used to alter national identity – specifically, in and through fiction. By altering preconceptions of existing places, literature alters the understanding of identity derived from them. In an editorial in The Cartographic Journal, Barbara Piatti and Lorenz Hurni write that “the distinctive tools of literary writing include, to name just one option, the ability to destabilize taken-for-granted geographies” (218). Both Death in Breslau and Lovetown destabilize the borders that were demarcated after WWII and the communist rule that followed, borders that worked to define Poland as a culturally homogenous state. Krajewski subverts the idea of Wrocław as a historically Polish city by setting the plot of Death in Breslau in a time when Wrocław was Breslau. The novel also points to the German origin of the Western parts of the current Polish state. Lovetown queers and estranges heteronormativity by describing locations where homosexual men used to meet in the communist period as well as inscribing their experience into the Polish literary canon.[9] By depicting repressed aspects of Polish history and overlaying them onto an existing city map, both texts question taken-for-granted identities constructed throughout the time of communist rule and beyond.

Hurni and Piatti give an idea as to how this contestation of Polish identity as homogenous, monocultural, and heteronormative may take place through literature. They show how literary texts can alter or unwork our understanding of physically existing places, which in the study of literary cartographies are referred to as geospaces. Furthermore, Hurni and Piatti remark that on the spectrum ranging from the very detailed and identifiable description of existing places to the creation of completely fictional worlds and settings, there are different intermediate points: “In-between, one can find various degrees of transformed settings, spaces, and places in fiction which are still linked to an existing geospatial section but are alienated by using literary means such as re-naming, re-modeling, or overlaying” (219). The renaming of streets in Death in Breslau functions as a form of the return of the repressed, a return to German Breslau as it existed before the end of the Second World War. Witkowski’s Lovetown, by contrast, others the city by fictionally overlaying its existing map with one commemorating the city’s queer life under communism. Here, memory and the return of the repressed occur by way of remapping, by describing in literary fiction that which has been made seemingly invisible in the geospace.

The link between the mapping out of the presence of a cultural past and the questioning of identity is strengthened by the use of intertextuality in both novels. Drawing on Julia Kristeva’s work, Renate Lachmann conceptualizes intertextuality as a form of memory of a text, a technique of recollection (35). By recollecting Sophocles’ Oedipus as well as Freud, Krajewski’s novel self-referentially points to the question of identity, which his text raises by bringing back the German Breslau. In the wider context of Polish culture, the text can be read as a quest for identity that takes the Polish reader into the German past of the city while also retracing the shift of the German-Polish border that is at the origin of the current Polish state. Witkowski’s use of intertextuality in Lovetown goes even further by quoting and provocatively paraphrasing a piece of canonical Polish literature by Adam Mickiewicz, a writer whose works are considered crucial to the formation of Polish national identity during a period in history in which the Polish state had been erased from the maps of Europe. The outrageous pastiche of Mickiewicz’s iconic quote self-referentially suggests the novel’s aim of othering the Polish literary canon that is so central to national identity-formation.

Restoring the German City Map in a Quest for Identity: Street Names as Protagonists

At the outset of the Second World War, the Second Polish Republic was a newly established state in the process of negotiating its identity. Reemerging in 1918 after 123 years of nonexistence, it became a multicultural and multilingual construct with various political factions and competing visions for the country. This quest for identity and independence entailed a military fight for the state’s future borders. As a result of the military conflict with Bolshevik Russia, cities like Vilnius (in today’s Lithuania) and Lviv (in today’s Ukraine) became part of the Second Polish Republic. After the Second World War, however, these eastern territories were lost to the Soviet Union.[10]

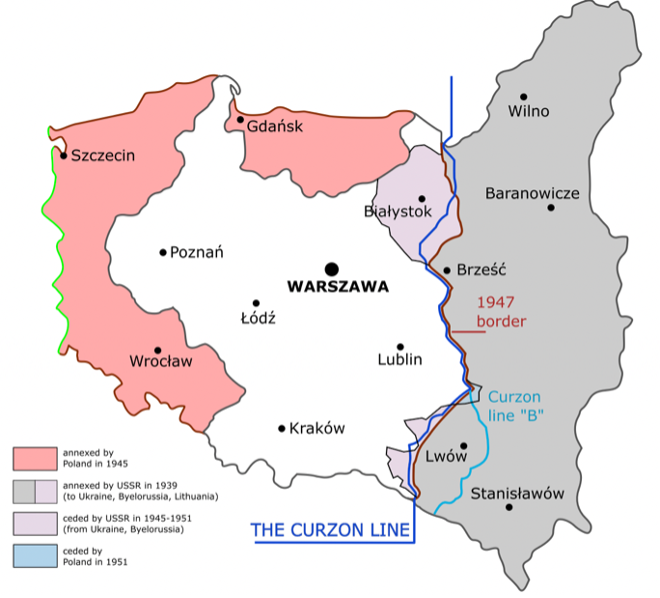

Fig. 1: radek.s, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

For comparison, the map includes the borders of the Second Polish Republic (1918-1939) as well as the borders established after the Second World War. The territory of the Second Polish Republic is represented by the white and grey areas on the map. The formerly German, now Polish territories are in pink. Losing these Eastern Polish territories during the Second World War to the Soviet Union meant losing “almost half the former territory of Poland” (Thum XXXVII). This “came as a shock to Polish society” (Thum XXXVII). To make up for these losses, the Allied forces and the Soviet Union decided that Germany would give up “East Prussia, eastern Pomerania, East Brandenburg, and Silesia, one-fourth of its 1937 territory, along with a number of significant cities, the most important of which was Breslau” (Thum XXXVII). [11] Not only was the country cut off from territories that “had profound significance for Polish national culture”, but the newly installed communist authorities of the country were faced with the task of having to incorporate the new Western territories into a newly drawn Polish state (Thum XXXVII).[12] The trauma of this “westward shift” was frozen in time, since the historical and political interpretation of the aftermath of the Second World War was determined by the new communist authorities, in their efforts at nation-building and self-legitimation. To make up for the loss of historically and culturally significant territories in the East, the new authorities were forced to construct a narrative that would cast the “westward shift” of Poland as a victory. Thum describes the approach of communist authorities as propaganda borne out of the necessity to incorporate former German territories into the new Polish state (190). The territories alongside the Oder/Neisse line were named “regained” or “recovered territories.”[13] The term evoked a foundation myth of Poland, which situated Slavic tribes and its first Polish kings in those territories. It implied a rightful restoration and attempted to construct these newly claimed territories as essentially Polish. A “Ministry for the Recovered Territories” screened the population of these territories for their Polish ethnicity, organized the expulsion of Germans, and supervised the settlement of Poles from territories lost in the east and elsewhere.

An integral part of the “regained territories” narrative was to eliminate and erase any traces of Germanness. This erasure ranged from the removal of monuments, plaques, street signs, and town signs to financial incentives for citizens with German names to Polonize them (Thum 263). Repressing the Germanness of the city as well as the rest of the “regained territories” posed an insurmountable challenge for local historians, whose focus on the narrative of the lucky return to the motherland made their studies of local history more aligned with propaganda than scientific academic research.[14] The narrative of the original Polishness of former German territories was also aimed at strengthening the claim of the rightfulness of the newly drawn, yet for decades uncertain, borders.[15]

Due to this historical context, the use of the German name for the city of Wrocław was considered taboo under communism. Even for an interval after the fall of communism and the ratification of borders by the German Bundestag and the Polish Sejm, the usage of the name “Breslau” might have been taken to indicate a revanchist attitude. That is why the recollection of the formerly German city was, at first, possible only in fiction. Breslau as a geospace in Krajewski’s crime novel brings back what has been repressed and seemingly erased by a necessary but false narrative.[16] The novel undoes this false narrative by way of remembering the German past of the city, mapping it out, describing its streets, mentioning German street names, and describing its buildings.

This historical context provides a backdrop and informs the reception of Marek Krajewski’s greatly successful mystery novel Death in Breslau, which was first published in 1999 and has since become a popular series.[17] The novel features the city of Breslau during the 1930s. Counsellor Eberhard Mock, the Deputy Head of the Criminal Department of the Police Directory in Breslau, is the series’ main protagonist. In the first book, Eberhard Mock is faced with the brutal and ritualistic murder of Marietta von der Malten, the teenage daughter of Baron von der Malten. The Baron belongs to an old German aristocratic family whose lineage can be traced back to the Crusades. The investigation begins in 1933 and comprehends the deciphering of mysterious writings left at the crime scene, scorpions, mental illness, unusual sexual practices, prophesies, curses, antisemitism, as well the increasingly difficult political climate of Mock’s work.

One could argue, however, that the true protagonists of the story are the German street names. By the simple act of using German street names, Krajewski’s writing fictionally undoes the process of Polonization undertaken by state authorities shortly after the Second World War. Gregor Thum explains that the process of “[incorporating] the German territories into Poland entailed a large-scale renaming operation. More than 30,000 place names, tens of thousands of natural features such as rivers, streams, lakes, forests, meadows, and mountains, as well as hundreds of thousands of streets and squares were to be given Polish names” (244). Krajewski’s prose restores the German map of the city, brings back its repressed past, and thereby reminds the Polish reader of the efforts to obliterate it. Here is Eberhard Mock arriving at his first crime scene:

They approached Sonnenplatz. The city pulsated with subcutaneous life. A tram carrying workers from the second shift at the Linke, Hoffmann & Lauchhammer factory grated on the corner, gas lamps flickered. They turned right into Gartenstrasse: carts delivering potatoes and cabbages crowded by the covered market, the caretaker of the art-nouveau tenement on the corner of Theaterstrasse was repairing a lamp and cursing, two drunks were trying to accost prostitutes proudly strolling in front of the Concert House with their parasols. They passed the Kothschenreuther and Waldschmidt Car Showroom, the Silesian Landtag building and several hotels. (…) The Adler drew up on the far side of Main Station, on Teichäckerstrasse, opposite the public baths. (19)

The novel not only restores the German map of the city but also documents the political changes that left their mark on it. The passage entitled “Breslau, the same May 13th, 1933 Half-Past Three in the afternoon” begins as follows: “The Bishops’ Cellar in the Schlesischer Hof Hotel in Helmuth- Brückner Strasse, in pre-Nazi times the Bischofstrasse, was famous for its exquisite soups, meat roasts and pork knuckle” (25). In the same passage, Mock reflects on his position within the criminal department and wonders if he would still have the power to fire a Nazi employee who refused to work with one of his best men, who happened to be Jewish.

The Criminal Counsellor was in a difficult position. (…) Now Mock was not at all sure he would have thrown that Nazi out of work. Much had changed since then. On January 31st, the post of Minister of Internal Affairs and Chief of the entire Prussian police were taken by Hermann Göring; a month later, the new brown-shirt Oberpräsident of Silesia, Helmuth Brückner, had moved into the impressive building of the Regierungsbezirk Breslau on Lessingplatz; and not quite two months later, the new President- shrouded in ill-repute- Edmund Heines had marched into the Police Präsidium of Breslau. A new order had come to pass. (…) From one day to the next, streets have been given the names of brown-shirt patrons. (36)

One can understand this passage as more than a reflection on the circumstances of introducing a new order, which involves a process of naming and renaming. It also marks a moment of self-reference since the text itself engages in the practice of restoring the streets’ German names. Furthermore, this moment of textual self-reflexivity may conjure up the renaming that took place in Wrocław after 1945, and again after 1989.[18] Mapping and remapping the city mirror the process of negotiating and forming an identity.[19]

The motto of Krajewski’s Death in Breslau is a quotation from Sophocles’ tragedy Oedipus the King: “All-seeing time hath caught//Guilt, and to justice brought//The son and sire commingled in// one bed (translated F. Storr)” (8). These lines relate to an ancient curse at the center of the novel’s plot. The murderer in the novel turns out to be a member of the Yazidi people. The Yazidis waited centuries to avenge one of their leaders whose children, a daughter and a son, were killed by one of von der Malten’s ancestors during the Crusades. The ritualistic revenge requires Baron von der Malten to suffer proportionally by also losing a daughter and a son. Within that context, the character of Herbert Anwaldt mirrors King Oedipus and his quest for identity. Anwaldt, who grew up in an orphanage in Berlin, arrives in Breslau at Baron von der Malten’s request to help Mock. Anwaldt ends up investigating his origin, which culminates in a moment of anagnorisis: he realizes that he is the illegitimate son of Baron von der Malten and his former maid Hanne Schlossarczyk, and therefore the half-brother of the murdered Marietta von der Malten. Sophocles’ text is referenced several times in the novel. On a train to Poland, Anwaldt happens to find a student-edition of Oedipus the King that has been left behind in his compartment. Reminded of how much he used to love ancient Greek, he leafs through the book. He wonders if he would still be able to understand the language. “He turned over a few pages and read verse 1068–Jocasta’s lines. He did not have the least problem with the translation. ‘Unfortunate one, may you not know who you are’” (240). This quote not only figures Anwaldt’s Oedipal quest of self–discovery within Krajewski’s novel but also points to the larger context of discovering and embracing the German past of a city that became Polish. It’s hardly coincidental that the character of Anwaldt, who is new to the city, serves as an occasion for a description thereof.

Baron von der Malten’s chauffeur helped him downstairs and into the car. They moved off. Anwaldt asked, with interest, about practically every building, every street. The chauffeur answered patiently: “We’re driving along Hohenzollernstrasse…on the left is the water tower…On the right, St John’s Church …Yes, I agree, it’s beautiful. Recently built…Here is the roundabout. Reichspräsidentenplatz. This is still Hohenzollernstraße…Yes, and now we’re coming on to Gabitzstrasse. Yes?… You know these parts? We’ll go under the viaduct, and we’ll be on your Zietenstrasse… The drive in the car gave Anwaldt the most enormous pleasure. (A beautiful city.) (151)

Krajewski’s text brings to the fore the otherness of Wrocław, the German Breslau that lies at its origin. It others the geospace. Germanness lies at the origin of now-Polish lands. It also reminds the reader of the pre-war borders between Germany and Poland, clearly demonstrating that Poland lay elsewhere. We see Anwaldt traveling to the Polish town of Rawicz. We see him working together with Polish police forces, and we read how his character experiences Poland as alterity. Polish street names are foreign to him. “He opened his notebook and read Ulica Rynkowa, 3. At that moment, a droshka drew up. Anwaldt, pleased, showed the cabman the paper with name of the street on it” (241). Anwaldt’s self-discovery in the city of Poznań is propelled by reading parts of a police report written in Polish. Discovering parts of oneself as “other” also describes the experience a Polish reader might have with Krajewski’s text. Encountering German street names in the Polish text confronts the reader with the German past of this now-Polish city.[20]

Breslaff as Lovetown: Witkowski’s Filthy Bible of Queer Street Life

Michał Witkowski’s Lovetown is another literary text in which Wrocław’s streets and the process of mapping play a vital role. Like the German history and culture of the “regained territories,” queer life was mostly absent from public discourse under communism.[21] And like German culture and the memory of German life in the Western territories, queer life, due to its otherness, posed a threat to communist authorities. Lukasz Szulc, in his study Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland: Cross-Border Flows in Gay and Lesbian Magazines, traces the emergence of a gay movement in the Eastern Bloc as well as its connection to Western activism. Szulc writes about the distrust homosexual groups faced from communist governments:

All homosexual groups in Eastern Bloc countries, as attested by the reports, shared the experience of being mistrusted by communist authorities, who seemed to be not much threatened by homosexuality itself but rather by the groups’ potential to destabilize communist states. (79)

The ‘organized otherness’ of homosexual groups was seen as potentially destabilizing. Szulc discusses this issue within the context of “homosexual self-organizing.” Any type of self-organizing, i.e. creating a group structure independent of communist institutions was treated with great suspicion by communist authorities. They made efforts to surveil homosexual groups as well as interrogate some of its members, but the archives of this surveillance have not yet been accounted for. Szulc deplores the uncertainty concerning the location as well as the exact number of personal files collected during Operation Hyacinth in 1985. Hyacinth was an undercover operation conducted by the police as well as the secret service whose aim was to “detain, interrogate, and register both actual and alleged homosexuals to create a kind of state ‘homosexual inventory,’ or ‘pink archive’” (106). After the fall of communism and suspicions that the pink files might have been used “in the 1990s for political blackmail,” the Polish advocacy group Campaign Against Homophobia suggested that the files should be destroyed. This could not be accomplished because the files could not be located. Szulc, however, argues for an active search for these files so that they can be studied and become part of history.

While there is indeed the possibility of misusing the files, their destruction would once again render homosexuals invisible within the official version of the history of communist Poland. (110)

Witkowski’s novel fills the blank pages of queer life during communism in Poland by focusing on the unofficial tales of homosexual men who lived through that time and mapping out their lives within the context of the city. The narrator of the novel presents himself as the author’s alter ego who interviews older homosexual men in Wrocław. By doing so, he writes a fictionalized oral history of queer life and humorously stages a claim for it to be included in the Polish literary and historical canon.

Witkowski considers his polyphonic tale of Wrocław’s queer culture during communism “a book of the Wrocław streets.” The Polish title contains the self-descriptive phrase “Plugawa Biblia”– which translates to “Filthy Bible.” It is a book of origination in the sense that it puts traditionally excluded people and activities on the map by writing about them. It is “filthy” in that most of the tales elicited by the author’s alter ego relate to the pursuit of sexual encounters. Furthermore, it is also “filthy” for being a “book of the streets”: queer life during communism did not have a place in society and had to take place at the margins – in parks, public restrooms, and railway stations. Furthermore, the “filthiness” is programmatic, since “Witkowski opposes his campy protagonists, with their untamed imaginations, destructive desires and complete lack of interest in social acceptance for their lifestyles, to the modern, emancipated and media-friendly gays” (Wodzyński 35).

Witkowski’s Lovetown begins with the narrator visiting a gloomy socialist apartment block and talking to Patricia and Lucretia, two older homosexual men who had their respective heydays during communism and whose quality of life has since deteriorated.

They refer to each other as she or her, call each other sister or girl and it wasn’t all that long ago that they were still picking up men in the park, behind the opera house, and the train station. Who knows how much is true, how much is legend, and how much is simply taking a piss. (5)

The author’s opening conversation with Patricia and Lucretia introduces these characters as not only experts on queer life during communism but also active participants in it. The conversation partially serves as an introduction to the terminology and phenomenology of queer life. The two men deliver some introductory remarks, explaining key concepts of their life such as the “picket-line” (cruising ground for sexual encounters, a public park) and the “grunt.”

‘What exactly is a grunt…?’ My question is drowned out by wild squeals. ‘What is a grunt? What is a grunt…? Christ, Christina! What exactly is a grunt? Fine, let’s pretend you don’t know. Grunt is what gives our lives meaning. A grunt is a bull, a drunken bull of a man, a macho lowlife, a con man, a top, sometimes a guy walking through the park, or passed out in a ditch or on a bench at the station or somewhere else completely unexpected. Our drunken Orpheuses! A queen doesn’t have to go lezzing around with other queens after all! We need straight meat! Grunt can be homosexual, too, as long as he’s simple as an oak and uneducated-because if he finishes school, he’s not a real man anymore, he’s just some intellectual. (12)

Their stories circle around other ‘queens’ with feminine nicknames and the locations they used to frequent in pursuit of sexual encounters. By giving a voice to these characters, Witkowski’s writing opens a space for a queer cultural history to unfold. It commemorates a culture and a way of life that existed only on the fringes of society, a culture that always lacked visibility and acceptance and which was organized around sexual desires. Lovetown functions as a literary cultural history of queer life in Wrocław, a life that never really had a place, and which was marked by lack and deprivation.

(…) satisfaction isn’t a word in their language. The only words they know are ‘hunger’, ‘frustration’, ‘cold night’, ‘wind’ and ‘come with me.’ A permanent stopover in the upper regions of the depths, between the railway station, where the pickings were slimmest, their miserable jobs and the park, where the public toilet was. (6)

The novel furthermore addresses the problem of historicizing a way of life that did not have a place, was focused on sexuality, and which unfolded in “informal and often unsafe cruising spots in parks, baths and public toilets” (Szulc 79).

Now they’re building a great big shopping mall in that park of theirs; they’re burying their entire history. Patricia insists she will protest. But she’s only kidding. More bitterly and sadly every time. ‘What can a bag lady like me do? Lay into Big Capital with my walking stick? Hit it over the head with my handbag? What should I tell them, that it’s a historic site? (7)

Patricia suggests that claiming a popular cruising destination as a historic site would be considered outrageous and therefore impossible. Witkowski’s narration of queer life strives for a place in the literary canon and on the map of the city. Through such a remapping of Wrocław, Witkowski’s novel lays a claim to the visibility and memory of queer life under communism. It queers the geospace. His novel functions as a literary and historical version of “queering the map,”[22] a virtual platform that “provides an interface to collaboratively record the cartography of queer life -from park benches to the middle of the ocean- in order to preserve our histories and unfolding realities, which continue to be invalidated, contested and erased” (Queeringthemap).

Most of the commentary on the novel focuses on the intricacies of translating the subcultural slang used by the characters when translating the novel into other languages.[23] Little attention has been paid to the use of intertextuality in Witkowski’s writing. However, in Lovetown, intertextuality establishes a link between topography, memory, and the questioning of identity. Lovetown others Polish identity by parodying a piece of literature that is considered central to the Polish literary canon and thus to the formation of national identity. After the introductory explanations and clarifications of queer terminology, the ladies of Lovetown begin to reminisce. One of the first memories they evoke is a scene of haunted visitation. They remember the Countess, a fellow ‘queen’, who was stabbed by a grunt she took home from the picket line. Patricia recalls this encounter with the ghost of the Countess, which occurred on All Saints Day during one of her many visits to the picket line. The ghost appears in front of Patricia and blasphemously parodies Adam Mickiewicz’s romantic drama Dziady. Dziady was written during the period of Poland’s fight for independence and features the romantic poet Konrad, who blasphemously argues with God over the reign of souls and claims to be able to create a happier nation and to be better than God. Konrad identifies with the suffering of the Polish nation and claims to be one with it. In the parody of Mickiewicz, the Countess comes back from the dead to chase sexual encounters. She, furthermore, identifies with the whole nation not because she suffers alongside it, but rather because she has had sex with a nation of grunts.

I cross myself, and she says to me: “Here did I come for grunt, here did I come for the holy rod, through these ruts and underbrush, e’en after death! We observe this day Forefathers’ Eve! Give me jism, give, and I to thee this moral lesson shall impart, that he who never…”

“Why, that’s blasphemy, you whore! To mock our nation’s literature even from beyond the grave!” ‘As a whore she always was exceptional! She continues her mocking, and says: “My name is Million! My name is Million!” she cries. “Because I’ve done a million grunts!” (15)

Patricia’s recounting of this apparition scene enacts “Forefathers’ Eve” or Dziady, the ancient Slavic feast commemorating the dead, from which Mickiewicz derives the name of his play. The feast is central to Mickiewicz’s drama, which is one of the core narratives constructing Polish identity. The verse parodied by the Countess reads in the original as follows: “I and the Fatherland are the same./ My name is Million, for the millions’ dole// I love as my own pain” (Mickiewicz 214). It represents the messianic mythology developed when Poland was partitioned and deprived of sovereignty. By parodying and mocking Mickiewicz, the Countess puts a queer spin on Polish nation-building narratives. The love for the nation is replaced by homosexual love with the whole nation. Furthermore, through this scene of the apparition and topographical anchoring, Witkowski’s text posits itself as a place of commemoration. Like Krajewski’s crime novel, the stories of queer life in Lovetown alter the perception of the city and expose its neglected otherness. By creating a space for otherness, and allowing it to become part of the story, literature becomes a mode of memory and a vehicle for the questioning of fixed identities.

Conclusion

As part of the “regained territories” and the country’s westward shift, the city of Breslau/Wrocław presents an exemplary geospace in which the link between German-Polish borderlands and the negotiation of Polish national identity after 1989 can be explored. The border changes after the Second World War were accompanied by a push toward cultural homogenization on the part of Polish communist authorities. The German past of the city was erased while homosexuality remained mostly invisible. Contemporary Polish literature plays a crucial role in bringing back these repressed subversive layers of the city. In Krajewski’s novel, the repressed German past returns by way of restoring the German map of the city, describing Breslau’s buildings, and naming the city’s formerly German streets. In addition, the novel’s intertextual references and plot both point to a link between the exploration of the German past of Wrocław and a quest for identity. Witkowski’s Lovetown creates a queer map of Wrocław by describing locations that were central to homosexual men in the city. Seemingly insignificant places such as the train station, parks, or public restrooms take center stage. Furthermore, by playfully paraphrasing Mickiewicz, the novel lays a claim for tales of queer life to be included in the Polish literary canon.

Works Cited

Freud, Sigmund (1933). “New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis.” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XXII (1932-1936): New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis and Other Works, 1-182.

Grębowiec, Jacek. Ziemie Odzyskane. http://www.polska-niemcy-interakcje.pl/articles/show/74.

Krajewski, Marek. Śmierć w Breslau, Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, 1999.

Krajewski, Marek. Death in Breslau: An Inspector Mock Investigation. Melville House, 2012.

Król, Mateusz Wojciech. “Representation of Communist-era Polish queers in translations of Lubiewo (Lovetown).” Queers in State Socialism: Cruising 1970s Poland (2020): 59.

Kuszyk, Karolina. Poniemieckie. Wydawnictwo Czarne, 2019.

Kuszyk, Karolina. In den Häusern der anderen: Spuren deutscher Vergangenheit in Westpolen. Aufbau Digital, 2022.

Lachmann, Renate. Gedächtnis und Literatur: Intertextualität in der russischen Moderne. Suhrkamp, 1990.

Mickiewicz, Adam, and Charles S. Kraszewski. Forefather’s Eve. Glagoslav Publications, 2016.

Piatti, Barbara, and Lorenz Hurni. “Cartographies of fictional worlds.” Cartographic journal 48.4 (2011).

Queeringthemap. https://www.queeringthemap.com. Accessed 29 May 2023.

“Return Of the Repressed.” International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. https://www.encyclopedia.com/psychology/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/return-repressed.

Szulc, Lukasz. Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland: Cross-border flows in gay and lesbian magazines. Springer International Publishing, 2018.

Thum, Gregor. Uprooted: How Breslau became Wroclaw during the century of expulsions. Princeton University Press, 2011.

Wodzyński, Łukasz. “The Prodigal Son of Polish Literature: Michał Witkowski and the Art of Self-Fashioning.” Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 98 no. 1, 2020, p. 35-59.

Witkowski, Michał. Lubiewo. Korporacja Ha!art, 2004.

Witkowski, Michał. Lovetown. trans. by W. Martin. Portobello Books, 2011.

[1]For a comprehensive take on how the concept of the “return of the repressed” developed in Freud’s oeuvre see (“Return of the Repressed”).

[2] The talks were mainly held between Churchill, Stalin and Roosevelt. For more details see Thum XXXIV

[3] In his study How Breslau became Wrocław during the Century of Expulsions, Gregor Thum describes this “westward shift” of Poland as a dual tragedy and considers the term “westward shift” to be a euphemism given the consequences it has had on the population of former German and former Polish territories. Millions of people were expelled and had to resettle, leave their homes, and suddenly embark on a journey into unknown conditions and territory. Furthermore, the “westward shift” of borders constituted an immense challenge for the People’s Republic of Poland. Therefore, Thum describes the suppression of the German past by Polish communist authorities as “necessary propaganda” (190).

[4] This private experience which the new Polish inhabitants of Wrocław have had with the buildings and things left behind by the city’s German population, is the basis for Karolina Kuszyk’s book In den Häusern der anderen: Spuren deutscher Vergangenheit in Westpolen.

[5] Szulc lists four main myths about Central Eastern Europe that are based on the dehistoricization of homosexuality: “The three most persistent myths about CEE with respect to LGBT issues are related to (1) the homogeneity and (2) the essence of the region, as well as (3) the teleological narrative of the CEE’s ‘transition’ after 1989 from communism to Western ideals of capitalism, democracy, and ethics. They are all based on yet another myth of (4) the near total isolation of CEE during the Cold War, and stem from the dehistoricization of homosexuality in the region.” (Schulc 5)

[6] These reports were published in English between 1982 and 1989 by activists in the West and were part of the Eastern Europe Information Pool (EEIP) program. The aim of this initiative was to “collect information about homosexuality-related issues in the Eastern Bloc, make contacts with local homosexuals and ‘encourage the forming of informal interest groups’” (Szulc 61).

[7] Following Szulc, who uses ‘homosexual’ instead of ‘gay’ for the purpose of “historical precision”, I will use the adjective ‘homosexual’ as well as queer to refer to gay men. ‘Queer’ denotes otherness which is a crucial point in this article.

[8] Regarding homosexuality in the public discourse, Szulc writes that “most of the time, the reports’ authors complained about the scarcity of homosexuality-related media content in the region or about the prejudices and stereotypes reproduces in existing media representations” (76)

[9] Łukasz Wodzyński points to the fact that “Witkowski introduced a new collective protagonist to Polish literary tradition: the pre-emancipation era queers (‘queens’), who in 1980 staled parks, public toilets and other ‘hunting zones’, searching for casual sexual encounters with heterosexual masculine types (‘grunts’).” (Wodzyński 35)

[10]Thum points to the fact that these eastern territories were already lost due to the Hitler-Stalin Pact. After the “German Wehrmacht invaded Poland from the west; on September 17, the Red Army followed suit from the east, maneuvers agreed upon between Berlin and Moscow in the Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 23, 1939” (XXXI)

[11]“Polish politicians participated only in a limited capacity in working out the country’s new borders. The Polish government in exile, which had not been informed of the basic decisions that had been made in Tehran, continued to demand the reestablishment of Poland’s prewar border in the east and a territorial expansion in the north and west (…)” (Thum XXXVI)

[12] “Although the Kresy, as the Polish territories in the East were referred to by Poles, were economically far less developed than the rest of the country, they had profound significance for Polish national culture. Here was the birthplace of national poets Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki and of countless other figures in Polish intellectual life, the home of Jozef Piłsudski, who founded the Second Republic of Poland in 1918, and the land of the wealthy Polish aristocracy, where Poland’s most magnificent estates and castles could be found. This territory also included the metropolises of Wilno and Lwów, which apart from Warsaw and Kraków were the leading centers of Polish urban culture, famous for their distinguished universities, libraries, archives, and art collections.” (XXXVII)

[13] Grębowiec discusses the many intricacies of this toponym.

[14]“They did not invent historical occurrences, but they constructed a historical continuity that would lead without disruption from the past to the present and thereby provide historical justification for Wrocław’s postwar situation. Silesia’s early Slavic-Polish history, the founding of the Wrocław bishopric in 1000 ce by Piast Duke Bolesław Chrobry, and the long reign of the Silesian Piasts offered historians manifold points of departure. (…) They functioned as the engineers of a new collective memory, designing an image of the past that overrode Wrocław’s foreigness and made it into an “age-old Polish city,” a place to which Poles could “return,” where they could find roots of their own nation and old Polish traditions upon which to build.” (Thum 217)

[15] Although the shift or borders was recognized in 1950 by the GDR and in 1970 by Western Germany, the status of the Oder/Neisse Grenze (Oder/Neisse line) had to be reaffirmed by the German-Polish border treaty after the fall of Communism in 1990. Only the ratification of this treaty in 1991 by the Bundestag and the Sejm settled the German-Polish border issue indisputably.

[16] See Thum on propaganda as necessity (190)

[17] The German translations of the book series include Der Kalenderblattmörder (2006), Gespenster in Breslau (2007), Festung Breslau (2008), Pest in Breslau (2009), Finsternis in Breslau (2012). The series has even inspired a musical. “Mock. Czarna burleska” (Mock. A Dark Burlesque) premiered at the Musical Theatre “Capitol” in Wrocław in 2019.

[18] Following the end of communism in Poland some street names have been changed to mark the political shift. In Wrocław, for example, First of May Square has been changed to John Paul II Square. For more on the changing street names in Breslau and Wrocław see Thum.

[19] For more on the process of renaming street names see Thum 244-266.

[20] After the Second World War, the new inhabitants of Wrocław were constantly confronted with the remainders of Breslau. They moved into former German houses and discovered things that were left behind. This experience was not part of public discourse but resulted in the creation of the adjective: poniemieckie (post-German/after-German). In her book Poniemieckie Karolina Kuszyk studied this history of buildings and things by talking to three generations of inhabitants of Wrocław.

[21] Szulc describes the situation before 1980 following: “In the PRL’s public discourse until 1980, male homosexuality was usually represented in stereotypical ways, either in a criminal context, especially in newspapers, or in a comical context, especially in films.”(99) He also points to the fact that there “breakthroughs in representing homosexuality in mainstream media” (76). In Poland it was the year of 1987 when a “boom of positive articles about homosexuality in Polish media” (77) occurred.

[22] https://www.queeringthemap.com

[23] See Król.