Merkel the German “Empress Dowager”? Reactions to the Syrian Refugee Crisis in China and other East Asian Countries

TRANSIT vol. 12, no. 2

Qinna Shen

Abstract

Taking a cue from a painting by Jiny Lan, a Chinese artist living in Germany, which captures Merkel’s refugee policy in 2015, the article examines both official and popular responses to the recent Syrian refugee crisis in China and other East Asian countries. In the painting, Merkel wears a Manchu-style headdress typical of women at the Qing court. Lan’s portrait of the German Chancellor resembles the Empress Dowager Cixi—one of the most powerful women in Chinese history, and a ruler with a contentious legacy. The article distills some of the major reasons for a positive or negative attitude toward accepting refugees among Chinese living in both China and Germany. In the coda, it briefly touches on reactions in Japan and South Korea to provide context and contrast.

Although popular opinion in China and within Germany’s Chinese communities is divided on the refugee question, there is little interest among Chinese in either country in building a Willkommenskultur. The massive influx of new immigrant groups led Chinese expatriates in Germany such as Jiny Lan to distance themselves from Merkel’s impactful refugee policy. Their political views tended to converge with those of Merkel’s critics both in the government and among the right-leaning populace. The apocalyptic equation of Merkel and the Empress Dowager Cixi taps into the fear that the end of Germany is near, evident in neologisms such as “Europastan,” “Deutschstan,” and “Francistan.” The refugee issue is an ongoing one. Merkel has by now modified her position, but the effects of her refugee policy in 2015 still remain to be seen.

When the Syrian refugee crisis rocked Europe in fall 2015, Angela Merkel prodded her nation to take up the challenge (“Wir schaffen das!”). Subsequently, over a million refugees entered Germany. Reactions to her momentous decision both within Germany and in the world were deeply divided (Alexander, 2017; Steinbeis and Detjen, 2019). The influx of refugees into Germany was vividly captured in a painting by a Chinese artist living in Germany, Jiny Lan. In The Crown (Die Krone, 2018), Lan painted Angela Merkel wearing a smug smile and a style of crown associated with royal women at the Qing Dynasty court. In Lan’s depiction, the chancellor resembles the Empress Dowager Cixi—one of the most powerful women in Chinese history, but also a leader with a contentious legacy (Figure 1) (“Jiny Lan”).[1]

A closer look reveals that the crown consists of a diverse group of people turned upside down—the uprooted and displaced refugees who weigh heavily on Merkel. The dangling ornament on the right of the headdress bears the colors of the German flag. Over Merkel’s right shoulder appears the Chinese character 令 (ling), signifying an imperial command or edict and alluding to Merkel’s “We can do it!” exhortation. The decorative pattern that adorns the shoulders of the royal gown is actually formed by endless refugees climbing up from the southwest and southeast, the directions from which refugees came to Germany. According to the artist, the ‘international people’ are borrowed from propaganda posters of the Cultural Revolution, on which Mao is extolled as the leader of the Third World. Lan said, “History has already shown that Mao’s ideology is not feasible. A ‘global solidarity’ did not come about through Communist ideology; on the contrary, the ‘international people’ are trying to get to capitalist countries, where human complexities are not ignored and a more pragmatic system prevails. Would the new endeavor of Frau Merkel succeed this time with ‘global solidarity’”? She leaves this question open for history to answer.[2]

The inspiration for this painting came from the artist’s ancestral history and childhood memories. Jiny Lan is the granddaughter of a member of the last emperor’s family. As a child, she saw her grandmother’s Manchu crown and asked her, “How could a woman wear such a cumbersome thing?” Her grandmother replied, “It is an honor to wear such a crown on the head.” What Lan wanted to convey in her portrait of Merkel was that welcoming refugees won Germany honor and respect from other countries, but it also imposed an onerous burden on the nation. As the artist observed, “The financial, moral and cultural burden that the refugees place on Germany is enormous” (Zhang, “Germany Gossip—Merkel or Cixi”; Zhang, “Mein Deutschland”). Lan falls back on her cultural heritage and visual reservoir to illustrate the dilemma for Germany. Artistically, the sinicized Merkel portrait is a compelling and unique creation and the fruition of cultural hybridization. Ideologically, however, the exotic appearance of Merkel creates a defamiliarizing effect that forces viewers to reexamine Merkel and her historic decision. Because the refugees and Merkel (aka: Germany) are inverted, the portrait underlines the tension between the two entities. The dangling status of the refugees might suggest that Merkel is using them as political ‘ornaments’ to increase her own standing, but in a way that ultimately makes her look ridiculous. The controversial Empress Dowager Cixi, known as a femme fatale figure, was blamed for the fall of the Qing Dynasty. Lan’s portrayal of Merkel as the German Cixi indicates her skeptical criticism of the chancellor, expressing an almost alarmist characterization of Merkel’s refugee policy as a harbinger of calamity for Germany.[3]

Did the expatriate artist capture Chinese views of Merkel in mainland China and in Germany? This article ventures to survey and analyze responses to the 2015 refugee crisis from China and other East Asian countries, a region that is often sidelined in the discussion of the crisis (Ostrand, 2015). Given the geopolitical and economic importance of these East Asian countries, integration of this region into this important debate is long overdue. The article turns to news coverage, social media posts, and microblogs in the German, English, and Chinese languages. Its task is to sample the vast sources of information in order to address questions that have not hitherto been discussed systematically: How did the Chinese government and Chinese people in mainland China and in Germany respond to the Syrian refugee crisis? What are some of the major reasons for a positive or negative attitude toward accepting refugees into their country of residence? Does popular opinion of Chinese people in each community align with the official policy of the country of residence? How does German-Chinese popular opinion compare with German popular opinion? Do expatriates tend to maintain the political views or foreign policies of their native country, or do they adopt those of the host country? And can expatriates who endorse the political views and foreign policies of host countries influence thinking in their native countries at the official or popular level? In answering these questions, the article seeks to bridge gaps between German studies, media studies, political science, Chinese studies, and refugee studies. By way of conclusion, the article will briefly touch on the reactions in Japan and South Korea to provide context and contrast. Using Germany as a reference point, the article shows both differences and similarities between East Asian and German responses. One major difference lies in the response of governments and the attitudes of their citizens toward welcoming refugees. The similarities are shown in the rise of racism and populist nativism in these countries.

Chinese Government Opinions on the Refugee Question

As refugees thronged into Germany in 2015, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hong Lei was asked at a routine press conference on September 11, “Has any other country asked the Chinese to accept Syrian and Iraqi refugees?” He did not answer the question directly but indicated China’s general willingness to cooperate with the European Union (EU) in addressing the refugee problem. He suggested that economic development in the affected regions could fundamentally solve the refugee problem, reflecting the official policy that also undergirds the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (“Central Committee”; “What’s Wrong with ‘Standing with Refugees’?”). Merkel visited China for the eighth time on October 28, 2015 in order to conduct trade negotiations as well as seek help in managing the refugee situation. Premier Li Keqiang told her that the Chinese government hoped for a diplomatic and political solution to restore stability in the region, but he argued that it would therefore be necessary to combat poverty and promote social and economic development in the affected countries (“Merkel erfolgreich in China”; Delfs and Donahue, 2015; “Pressekonferenz”).

The German ambassador Michael Clauss said on May 5, 2017 at the embassy in Beijing that the BRI “could make a significant contribution to alleviate the root causes of migration. That’s obviously very important to us, because Germany is particularly affected by the refugee crisis” (“Where the Rubber Meets the ‘Belt and Road’”). The New Silk Road, another term for the BRI, constitutes a new reality to which most people must still adjust. For instance, it is now possible for China to ship goods by rail to the regions where refugees are residing. While researching the refugee situation in Germany in October 2015, Liu Yiqiang, a lawyer of the NGO “International Law Promotion Center” (CIIL) that initiated the “German Syrian Refugee Camp Research Project,” learned from officials in Berlin that Germany was in urgent need of beds for refugees and had turned to the Red Cross in America and Canada for help. Liu wondered, “Why didn’t Germany think of asking China? The new Chongqing-Xinjiang-Europe rail route stretches from Chongqing to Duisburg and can transport goods from China to Germany within two weeks” (Zeng, 2015). China delivered aid worth over $40 million in the first half of 2017 to Syria directly, as well as a total of 5,404 tons of rice to the northwestern city of Latakia, and provided both personnel and material support in Syria’s reconstruction (Gao, 2017; “China Delivers Food Aid to Syria”).

However, China’s commitment to humanitarian aid contrasts with its reluctance to host refugees. Hua Liming, a former Chinese ambassador to Iran, said, “China has been playing an increasingly active role in the Syrian conflict, but I don’t think China is considering to provide shelter to people fleeing Syria or other war-torn Middle East nations” (Shi, 2017). On June 23, 2017, while meeting with his counterpart in Lebanon, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi said, “Refugees are not migrants. The refugees scattered around the world should return to their homeland and rebuild it. Not only is this the wish of every single refugee, but it is also in line with the goals of international humanitarian efforts and part of the UN Security Council resolution on the political solution to the Syrian question” (“China: Flüchtlinge sind keine Migranten”). Wang’s assertion that returning to their homeland is the wish of every single refugee is the boilerplate justification for the Chinese government’s own repatriation policy, which it applied to 30,000 KoKang refugees from Myanmar in 2009, as well as to North Korean and most recently Rohingya refugees. In Germany, only Deutsche Welle (DW) pieces written by the Beijing-born columnist Zhang Danhong and conservative media such as Tichys Einblick and Contra Magazin reported on Wang’s statement (Zhang, “Mein Deutschland”; Steiner, 2017). The far-right newspaper Tichys Einblick explained that the Chinese foreign minister’s clear statement should calm those tens of thousands of mainland Chinese who had anxiously discussed on social media China’s possible embrace of Middle Eastern refugees (“China: Flüchtlinge sind keine Migranten”).

Popular Opinion and Anti-Refugee Arguments in China

According to a Spiegel article published on May 19, 2016, Amnesty International conducted a survey asking thousands of people from 27 countries whether they were willing to accept refugees into their country, their city, and their homes. China topped the Refugees Welcome Index, even outshining Germany. 94 percent of the Chinese said they would welcome them into the country and 46 percent said they would welcome them into their home (“Refugee Welcome Survey 2016”; “Amnesty-Index”; Drzymalla; Halloran). This result is rather surprising and contradicts other polling results. According to a Douban post published on October 22, 2015 by a blogger nicknamed Mr. Penguin, the majority of netizens on Chinese social media were antipathetic toward refugees fleeing to European countries, let alone to China. Mr. Penguin observed that in China it is considered “politically correct” to mock Merkel as a Madonna or Virgin Mary figure and to ridicule leftist thinkers in the West as baizuo (White Left). The derogatory term baizuo emerged during the global rise of populist nativism and refers to liberal media, progressive intellectuals, and celebrities (“Why Scolding ‘Virgin Marys’”).

On June 20, 2017, World Refugee Day, the UNHCR and Yao Chen, China’s first Goodwill Ambassador to UNHCR, held a charitable event in Beijing, where the film Welcome to Refugeestan (dir. Anne Poiret, 2016) was screened. The UNHCR posted on Weibo that this event was to “pay tribute to the world’s 65.6 million people who are displaced and homeless, and to pay tribute to all those who support and care for the refugees” (Figure 2) (Koetse; “What’s Wrong”; Newhouse).[4] Official Chinese media, including People’s Daily and CCTV, also reported sympathetically on the refugees and China’s contribution (“65,600,000 Refugees Expect Acceptance and Integration”).

The Weibo post unexpectedly caused an internet uproar and received 29,774 predominantly negative comments versus 2,373 likes. Netizens assumed that the UNHCR, Yao Chen, and the media, were all lobbying the Chinese government to accept refugees from Syria and North Africa and thus resorted to social media and microblogs to preempt such a move. An online news story falsely claimed that “Local people in Sanhe [in Henan Province] confirmed it. It’s real. Refugees get free housing. They do not need to work. It’s shocking, not just in Beijing, UNHCR has refugee settlements in more than 20 cities in China. Refugees get allowances of over ¥3,000 per month” (“Let Germany Tell Yao Chen What Becomes of Standing Together with Extremist Refugees”). Alarming and fact-bending posts and online trolls stoked people’s fear (“Let Germany Tell Yao Chen”; “History Warns China”; Li; “Internet Rumor”; “Why Do Chinese Dislike Refugees?”).[5] Panic spread and anonymity allowed racist, nativist, and Islamophobic comments to flourish (“What’s Wrong”).

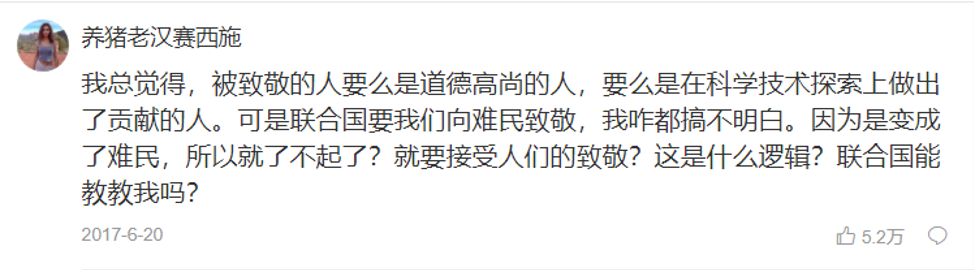

One netizen took issue with the wording “pay tribute to the refugees” in the UNHCR message: “I have always thought that those to whom we pay tribute either have high morals or have made contributions to scientific and technological research. But the UN wants us to pay tribute to the refugees, which I don’t understand. Just because they have become refugees, they’ve become amazing? And deserve the respect of others? What logic is this? Can the UN enlighten me?” (Figure 3) (UNHCR Weibo post, June 20, 2017).

In comparison to the UNHCR post, which was liked only 2,373 times, this comment was liked about 52,000 times.

A Weibo user launched an online poll, asking the public: “Would you like China to accept refugees?” In a short period of time, 180,000 people voted but only 2.5% indicated willingness to accept refugees (Figure 4) (“What’s Wrong”).

On June 22, 2017, the Guangdong Communist Youth League conducted a similar online survey but phrased the question slightly differently: “The Middle East refugees continue to increase. Does the Chinese government have the responsibility to accept refugees?” Out of 10,000 votes cast, only 51 people, i.e., 0.5%, agreed to “accept the Middle East refugees because they are in need.” (“What’s Wrong”; “The Chinese Arrogantly Refused”; “China Plans to Admit Refugees”; “Central Committee”). A word of caution needs to be said about these online surveys and to what extent they accurately reflect popular opinion. Respondents to online polls comprise a limited segment of the population, i.e. those who have internet access and those who care enough about the issue to vote. Moreover, polls are sometimes biased and are targeted at interest groups who have a strong emotional investment in the issue. In this case, given that the Chinese administration was already unwilling to accept refugees, this landslide disinclination to accept refugees had no influence on politics, but it revealed the sentiments of a certain fraction of the public and exposed the Islamophobia and racism of some bloggers and commentators. Many also used the refugee situation as leverage to critique elements of China’s domestic policy, such as the one-child policy, the BRI, and tolerance of domestic poverty.

Similarly, while many Germans enthusiastically unfurled banners to welcome arriving refugees in 2015, this euphoria was hardly shared by the Chinese community in Germany. Many of them felt concerned or even alarmed (“Chinese in Germany Are Worried”). According to DW’s Chinese-language site: “On Weibo, WeChat, and other social media, we often see similar comments: ‘Be careful when you go out’; ‘Germany’s Madonna Cancer’” (Wang, “The Refugee Problem”; “Do Germans Suffer from ‘Madonna Cancer’?”). Chinese who had already settled in Germany adopted the position that “the boat is full” (“How Has He Qinglian Demonized Merkel?”). The fear of competition between different immigrant groups is not a new or rare phenomenon. In addition to raising economic concerns, many Chinese in Germany dreaded social problems that might be caused or exacerbated by refugees (“Chinese in Germany Are Worried”). Some others said that although they did not oppose accepting refugees, the rapid admission of large numbers of refugees since September 2015 had created a huge security hazard for the host society (“Refugees Flooded into Europe”). Other complaints about the refugees were often related to everyday inconveniences, such as waiting longer in line when registering for German language courses (“Germany Has So Many Refugees”).

Analysis of the negative sentiments documented above yields a variety of arguments against accepting refugees cited by the Chinese government and netizens.[6] The first major argument concerns the question of international responsibility for the Syrian refugee crisis and relates to the Chinese critique of US foreign policy. The Chinese government has long maintained that the US-led Western coalition has attempted to impose its version of democracy on the Middle East by becoming involved in wars, directly or indirectly, in Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, all of which have triggered waves of migration both within these regions and into Europe. On the eve of Syria’s civil war, People’s Daily (February 2011) criticized the US’s self-perception as a “protector” of Arab citizens as a product of its arrogance and immoral superiority complex. In turn, the news outlet contrasted this American paternalism with China’s call for the self-determination of Arab citizens (Ren 269). In 2011, the Chinese government aligned itself with Russia and vetoed three UN draft resolutions that threatened Syria with possible sanctions, marking a shift from China’s usual pattern of abstention in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) (Ren 263). The Syrian refugee crisis seemed to confirm China’s warning that America’s purported protection of human rights and civilians would only cause a larger humanitarian disaster (“Libya Conflict”). In an October 2015 opinion piece in People’s Daily, Wu Sike, a former ambassador to Egypt and Saudi Arabia and former Special Envoy on the Middle East, argued that the U.S. and Western agenda to “democratize” the Middle East lies at the root of the refugee crisis (Liang; Huang and Li 69; Song, 2015, 45; Zhan). Shen Jiru of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences also opined that it was not fair to expect a developing nation like China to “clean up the mess” in Syria left by the US-led coalition (Shi).

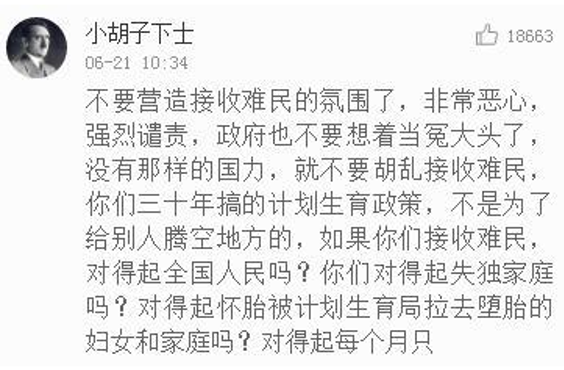

The second argument concerns the capacity of the Chinese population to accommodate refugees in relation to China’s one-child policy. In reaction to the above-mentioned UNHCR Weibo post, a netizen who nicknamed himself “Moustache Corporal” and used a headshot of Hitler as his profile image brought up China’s one-child policy and its draconian measures such as forced abortions, sterilizations, fines, and career penalties (Figure 5). His choice of avatar was extremely provocative and suggests that he was a neo-Nazi or at least an online troller.

He wrote:

Don’t create an atmosphere conducive to receiving refugees. It is very disgusting and I condemn it strongly. The government should not be overly magnanimous. If you do not have that national power, do not accept refugees indiscriminately. You have enforced the one-child policy for 30 years, not just to make space for other people. If you accept refugees, how can you face the people of this country? How can you face those families who have lost their only child? How can you face those women and families who were forced to abort their baby? …

His view is similar to what another netizen wrote in a piece titled “China’s Family Planning Is Not Intended to Make Room for Refugees.” That article was shared over 80,000 times before it was removed and deleted by internet censors due to its inflammatory language (“Internet Rumor”; “China Plans to Admit Refugees”). However, even a professor from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Xi Wuyi, argued that if China starts to accept refugees, “we are forced to give up our children to save space for foreigners.” (Wang, “Why Do Chinese Reject?”). Because China’s one-child policy targeted only the majority Han ethnic group, and not Muslim and minority groups, the debate stirred up old resentment among Han Chinese toward Muslim refugees (Wang, “Why Do Chinese Reject?”). However, despite the one-child policy, China has a huge population, which means the country’s economy does not depend on immigrants or foreign migrants for labor, as Germany’s does. Especially now that the government has relaxed its one-child policy, China is more likely to rejuvenate its native population, resulting in a native-born labor market that will be self-sufficient.

The third major anti-refugee argument stems largely from the idea that refugees would add a financial burden to the host country. Some Chinese-language blogs I encountered contain statistics showing how much each refugee would cost German taxpayers per month. The authors of these blogs believe that these refugees are economic migrants who want to take advantage of Germany’s (also Sweden’s) generous welfare system, which is why they did not want to stay in relatively poor Balkan and Eastern European countries (“Sweden under the Scourge of the White Left”; “Why is Sweden More and More ‘Dangerous?’”). Bloggers also brought up domestic poverty, pointing at the gap between the rich and the poor in China. As one netizen wrote, China is the biggest developing country and has its own impoverished population who “look as wretched as the refugees” (“Should China Accept Middle Eastern Refugees?”). Another commentator, equating Chinese economic migrants with refugees, remarked, “Helping [China’s poor] so as to reduce the flow of refugees out of China and into the international community would be China’s major contribution to reducing the world’s refugees” (“The European Response”). As Lili Song, a professor of law at the University of Otago in New Zealand, points out, China has ranked as a top-20 refugee-producing country every year since 2003 (UNHCR, Global Trends 2015, 56; Song 143).

Similar economic considerations led some critics to take issue with the government’s magnanimity toward other countries. During a 2015 UN summit, for example, President Xi pledged $2 billion and announced major debt forgiveness to assist poor countries. The international community naturally welcomed the move, but domestic critics complained about China’s “foreign-bound munificence,” arguing that the government had overspent on international philanthropy when a large population at home was still living below the poverty line (Liang). It is possible that this argument masks a domestic critique of the BRI, President Xi’s signature project. Because open critique of this major state initiative would be risky, the refugee controversy may have been exploited as a proxy platform to debate domestic policy.

A fourth major argument surrounds security concerns. The series of terrorist attacks and sexual assaults that rocked Europe in 2014–2016 was frequently attributed by netizens to Muslim refugees and immigrants. Some of the victims were Chinese. A family of four from Hong Kong were injured in the train ax attack in Würzburg carried out by an Afghan asylum seeker on July 18, 2016 (“Condition of Hong Kong victim”; “Hong Kong victim”). The Chinese student Yangjie Li was raped and murdered in Dessau in May 2016, but it turned out that a young German couple committed this hideous crime (“Man sentenced”). When two Chinese female students at the University of Bochum were raped in 2016 by a 32-year-old Iraqi refugee, one can imagine the panic such crimes caused in Chinese communities (“Man jailed”). According to one article (“Chinese Students Abroad”), some Chinese female students would no longer attend classes after four in the afternoon. They used to carry pepper spray in their backpacks, but now they would hold it in their hands while walking. If they went home late at night, a boyfriend or husband would pick them up. The former sense of security had vanished, and netizens questioned Merkel’s refugee policy more vehemently (Yu, “No Longer Feeling Secure”). Chinese-language social media and microblogs were inundated with reports of terror attacks in Europe and rising crime rates.

These reports played into the hands of authorities back in China. Chinese media coverage of attacks in Europe reinforced government propaganda stressing that it was necessary to adopt hardline measures against China’s own Muslim population in Xinjiang. From 1990 onward, Uyghur terrorists carried out numerous attacks against civilians, security forces, and (pro-) Chinese officials, and the Chinese government responded with a ruthless crackdown on the Uyghurs (Tanner; Chung; “China Mass Stabbing”; Wayne, 2008; Gohel). Thus, the refugee crisis fed preexisting domestic fears of terror attacks. The government believed that terrorists connected with the Syrian opposition would infiltrate Xinjiang and converge with separatist forces. The Chinese foreign minister highlighted the alleged connection between militants from China’s Turkic and Muslim minorities and Al-Qaeda (Ren 271).

A fifth argument for not accepting refugees, and one that does not rest on blatant Islamophobia, is that the refugees themselves do not want to come to China—a claim that is also supported by the relatively small number of refugees from the Middle East and Northern Africa who apply for sanctuary in East Asian countries. One commentator stated, “To be fair, it is not that China has explicitly refused to shelter Syrian refugees or those displaced by war and conflicts in the region. More importantly, refugees from the Middle East usually choose Arab nations or developed countries, such as the US and Europe, instead of China” (Shi). The Chinese language admittedly poses a barrier to adaptation and integration, and Li Guofu, a Middle East specialist with the China Institute of International Studies, stated that China was not an ideal destination for Middle Eastern refugees due to religious, cultural, and political considerations (Shi). As for refugees already in China, they are portrayed as unwilling to assimilate (Wang, “Why Do Chinese Reject”). It is difficult for Muslims to defend themselves against rumors and perceptions.

Finally, widespread anti-refugee sentiments in the rest of the world – frequently propagated by right-wing populist parties – have swayed public opinion. Chinese microbloggers often repeat the rhetoric of conservative politicians in Hungary and Poland, affiliates of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and movements such as Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the Occident (PEGIDA). Anti-refugee articles reporting on, for example, 550,000 rejected asylum seekers who still live in Germany, or on corruption and profiteering among those responsible for settling refugees and managing refugee camps, have been translated from Western languages into Chinese and circulated online (“550.000 abgelehnte Asylbewerber”; Dassen, “Asylindustrie”; Dassen, “A Hidden and Filthy Refugee Industry”). Videos of common citizens, such as of an old lady in Hamburg vehemently relaying her anti-refugee arguments, were broadcast on Chinese websites with subtitles (“Germany Has So Many Refugees”).

He Qinglian, a Chinese-American blogger for Voice of America, wrote a dozen Chinese-language articles demonizing Merkel and the so-called “white left” in the West (He). He’s writings are a quintessential example of post-truth and populist blogging. Two other Chinese bloggers challenged He, pointing out the misleading examples, deceptive logic, and ridiculous arguments in He’s diatribes; the bloggers were subsequently attacked by He on Twitter (“How Has He Qinglian Demonized Merkel?”). This is just one example of how Chinese communities were divided on the refugee question.

The views of some vocal Chinese netizens appeared closer to those of populist right-wing parties, conservative politicians, and anti-refugee factions or individuals in Europe. In any case, some Chinese netizens believed that leftist politicians in Germany welcomed refugees as a political strategy because descendants of these refugees would never vote conservative (“Has China Accepted Refugees Before?”). But the political self-interest of the “white left” would lead to the “Islamization of German society” and “the imminent demise of European civilization,” and ultimately to the creation of a new caliphate: “Europastan,” “Deutschstan,” or “Francistan” (Wang, “The Refugee Problem”). On bbs, a microblog site popular among overseas Chinese, another Chinese émigré published an opinion piece that labeled Merkel as the “Female Hu Yaobang” (“Shoot Yourself in the Foot”). Hu was the Party Secretary whose death sparked the 1989 Tiananmen student protests. Hu was known for having implemented the most tolerant and relaxed policies toward the Uyghurs and Tibetans since the Communist reign in China. Some praised his pro-minority policies as having a stabilizing effect on those regions in the 1980s, whereas others blamed him for planting the seeds for separatism and terrorism (“Hu Yaobang’s Xinjiang Policy”; “Should Anyone Dare to Advocate Hu Yaobang’s Ethnic Policies?”). The blogger who compared Merkel to Hu was criticizing her tolerant policies toward Muslims as historical and political mistakes.

Pro-Refugee Arguments in China

As in many other nations, the refugee crisis was a polarizing topic in China and within overseas Chinese communities. In various Chinese-language outlets, writers articulated the humanitarian as well as pragmatic reasons that led the German government to accept refugees , but I will not repeat these views here (“Why Was Germany Willing to Accept?”). Instead I will summarize some arguments advanced by Chinese netizens who believed that China itself should admit refugees. Generally speaking, these writers advocated compassion and tolerance for refugees, appealing to historical patterns and human sympathy rather than to the nationalist or nativist sentiments commonly expressed by conservative commentators.

A recurring pro-refugee argument is that many Chinese were once refugees themselves and should be able to commiserate with the new refugees. From the 1950s to the 1970s, over 100,000 Chinese fled Maoist China for Hong Kong, where residents not only welcomed these refugees from the mainland but voluntarily protected them (He, “Forgotten Stories”). In the late 1970s and early 1980s, many ethnic Chinese fled Vietnam for other countries including France, Germany, and China (Li). According to UNHCR’s “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2017,” the US, for example, received 17,400 asylum applications from China in 2017, contributing to a total of 89,500 pending asylum cases from China.

Another pro-refugee argument points out that (overseas) Chinese have been victims of racism, and so the Chinese should learn a lesson from history and not continue the vicious tradition of racist expulsion (“Why Do Chinese Dislike Refugees?”). Hu Wenhui, who has written on the history of discrimination against Chinese immigrants especially in the US, warned other netizens of their inappropriate behavior. Hu pointed out that Islamophobia is similar to the “Yellow Peril” rhetoric from over a century ago, only today it is the Muslims who are dispersed around the world and living in diaspora.[7] In 2017, a retailer at the Leipzig online store Spreadshirt, which provides a platform for vendors to sell custom t-shirts, sold clothing with the catchphrases “Save A Dog, Eat A Chinese” and “Save A Shark, Eat A Chinese,” causing outrage among Chinese communities. The company dismissed the complaints, maintaining that the catchphrases were mere jokes that appealed to some people more than others (Xie). It finally stopped selling the t-shirts after the Chinese embassy in Berlin got involved (Khoo; Herreria).

Some sober netizens denied that refugees posed any danger for Chinese in Germany. A professor from Zhejiang University who was on a business trip in Germany chastised fellow Chinese as “more nervous than Germans.” He observed that, despite the recent attack in Munich, Berliners were celebrating Love Parade. He could not share the anxiety of other Chinese in Germany: “Germans are, relatively speaking, a mature people. The [Munich attack] was serious for administrators, and there are more police patrols and police cars on the street, but average people are not too affected.” He admitted that judging by social media, most of his friends and acquaintances, some of whom were applying for German citizenship or were already naturalized citizens, were almost unanimously opposed to the refugee influx (Zhao). Another sober-minded netizen also commented that “The impact [of the refugee influx] is for real. But it is an exaggeration to suspect every tree or bush as an enemy soldier.” He continued, “Except for a tourist friend who was pickpocketed in Berlin, I have never heard of any other bad things that happened to people I know. The real Germany is safer than the Germany portrayed on WeChat or Weibo” (“Germany Has So Many Refugees”).

A fourth pro-refugee argument invokes universal values and China’s responsibilities to the global community. The dean of Beijing Foreign Studies University’s law school, Professor Wan Meng, said at a press conference on the “Syrian Refugee Crisis Investigation Report,” held by the NGO “International Law Promotion Center” (CIIL) on November 2, 2015: “Refugees are in fact far away from us, however, they are also very close. Why? The world’s affairs are China’s affairs. China’s affairs are also the world’s affairs. China has 1.4 billion of a world population of 7 billion. China’s GDP is the second largest in the world. Chinese people are everywhere in the world and we should carry responsibilities” (Zeng). This Chinese NGO conducted field work on Syrian refugee camps in Germany from October 15 to 19, 2015, and according to their research report, the refugee crisis posed a potential burden for China, yet it also provided a rare opportunity for increasing diversity in Chinese society. Seizing this opportunity at the right time would fundamentally strengthen the relationship between China and the world and would allow China to evolve from a nation state into a “world-class country”; the report maintained this was a responsibility that China could not dodge and an opportunity for China to rise (Zeng). Moritz Rudolf and Angela Stanzel have also argued that more financial aid from Beijing to curb the refugee crisis would be a “low cost, low risk engagement,” especially when compared to the billions of U.S. dollars China has pledged to the BRI; indeed, it could turn out to be a great PR coup for Beijing. Arguments such as these assert that supporting refugees is not only the right moral decision but can be mutually beneficial in the long run.

* * *

This article has surveyed media and web sources to showcase official as well as popular responses from online communities primarily in mainland China and in Germany. Ultimately, the Chinese government has a tendency to adopt economic solutions for what Westerners frame as political problems. Although popular opinion both in China and within Germany’s Chinese communities is divided on the refugee question, there is little interest in building a Willkommenskultur. Islamophobic as well as non-Islamophobic arguments against hosting refugees have gained mainstream acceptance. Anti-Muslim sentiments in China feed on accounts from Europe, and Chinese media have encouraged the public to support national security measures in order to prevent China from becoming another Europe seemingly sinking into chaos. At the same time, the Syrian refugee crisis is also invoked as a rhetorical device to criticize domestic policies in China. As shown here, the massive influx of new immigrant groups led Chinese expatriates in Germany to distance themselves from Merkel’s impactful refugee policy. Their political views tended to converge with those of Merkel’s critics both in the government and among the right-leaning populace. As Jiny Lan’s portrait illustrates, even though Merkel was at the height of her political power, her popularity suffered in the wake of the open-door policy. The portrait is now hanging in the office of none other than the FDP Chairman Christian Lindner, who refused to build a Jamaica coalition with Merkel after the 2017 election. Whereas Lindner certainly would not hang a conventional portrait of Merkel in his office, the outlandish, Chinese-inflected portrait of Merkel in the image of the Empress Dowager was provocative and interesting for a politician like him. Lindner found it “fascinating to hang in his office this portrait of the Chancellor in such a tantalizing artistic representation, infused with a message and associated with an empress who has the power to command unconditional obedience” – obedience that his party was not willing to deliver (Zhang, “Mein Deutschland”). The portrait itself forms an hourglass shape and invites inversion (Figure 6). Lindner said jokingly, “This artwork is a kind of mood indicator. Maybe others could tell my mood in the future by how the picture is hung” (Zhang, “Mein Deutschland”). Lan’s presentation of her artwork to an opponent of Merkel further indicates her alliance with critics of Merkel.

The apocalyptic equation of Merkel and the Empress Dowager Cixi taps into the fear that the end of Germany is near, evident in neologisms such as “Europastan” and “Deutschstan.” Vis-à-vis the Syrian refugee crisis, the expatriates have not swayed the public views of their country of origin in favor of the official policy of their country of residence. In fact, through their negative social media posts about the refugee influx, they may have reinforced mainlanders in their convictions.

The refugee issue is an ongoing one. Merkel made it clear that helping refugees was no mistake, since the alternatives in 2015 were probably worse, but nobody, including Merkel, wants a repetition of 2015. In 2019, when 12,000 refugees were lingering in the Balkan region, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, the CDU president at the time, reassured constituents that “everything will be done so that 2015 does not repeat itself” (Graw). As this article is about to appear, in March 2020, throngs of refugees are stranded at the Turkey-Greece border, awaiting entrance to Germany and other European countries. This time, Merkel made known that the “loss of control” (Kontrollverlust) of 2015 should not be repeated (Riegert). The majority of German politicians no longer want Germany to singlehandedly intervene on behalf of the refugees (Hille). Merkel no longer appears as an empress giving out orders (令 ling) as in 2015; instead, she wants to coordinate with other European states before taking action.

Coda: East Asian Responses to the Refugee Crisis

China, Japan, and South Korea are all signatories to the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol. The three governments as well as private donors in these countries have contributed financially and otherwise to alleviate the refugee situation. Japan consistently ranked among the top five donors to UNHCR, and China’s contributions increased annually in the past five years, though it still lags behind its East Asian neighbors (“Contributions to UNHCR”). Yet, both Japan and South Korea have maintained extremely strict procedures for accepting refugees, including a very long and slow vetting process, despite the rising number of applicants. During the onset of the refugee crisis, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said on September 22, 2015 that his nation must attend to the needs of its own citizens before opening its doors to refugees (“Japan Says It Must Look after Its Own”). Bureaucratic hurdles also make it almost impossible for applicants to receive legal refugee status (“UNHCR Asylum Trends 2013”; “No Entry”; Murai; Craft; Lee; “Japan Rejected over 99%”; “Not Welcome”). The Japanese government defines refugees as those who are individually targeted and persecuted, regardless of whether they belong to a persecuted minority or are fleeing war or conflict. Japan also requires that refugees apply in person and present valid identification cards. Japan fears that if it starts admitting more refugees, it would set a precedent for potential refugees from North Korea. Accepting refugees could nevertheless be a win-win situation for Japan because, like Germany, Japan is a wealthy nation with a falling birthrate and a shortage of labor (McCurry). In Japan, pro-refugee marchers carried signs such as “Refugees Welcome” or “No One Is Illegal” (McCurry; “Japan”). In South Korea, a very low percentage of applicants is granted refugee status, for example, 1.5% in 2017 (Rich and Bison). Similar to what the West German government did for East German escapees before the fall of the Berlin Wall, South Korea automatically grants citizenship to North Korean defectors who flee to South Korea. South Korea is committed to accepting refugees from their northern neighbor, but not from elsewhere (Lee). When 561 Yemeni refugees arrived at the visa-free resort island of Jeju in 2018, there arose a political crisis in South Korea (Park; Hirst).

There are encouraging signs that these countries are becoming more engaged in the global refugee crisis and have been making legislative and administrative efforts to regulate the procedure. South Korea is the first country in East Asia to have introduced a Refugee Act, and both South Korea and Japan have implemented legislation on relocating refugees (Lee 4). The Chinese government has delegated the responsibility for screening refugees to the UNHCR office in Beijing (“The European Response”). As Lili Song pointed out, China gradually emerged as a transit country and destination for refugees and included for the first time in Chinese law, its 2012 Law on Exit–Entry Administration, an article on treatment of refugees (160). Although these East Asian countries admit few refugees officially, they allow a much greater number of asylum seekers to remain on their soil temporarily, out of humanitarian considerations. But the East Asian countries could learn from Germany’s example in improving their legal framework for determining refugee status and offering subsequent support for the social integration of asylum seekers. In so doing, East Asian countries would duly assume a greater share of humanitarian responsibilities, as befits their economic and political stature in the world.

***

Acknowledgements

I thank the Office of the Provost of Bryn Mawr College for supporting this project with a generous “Promoting the Value of the Humanities” grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Earlier drafts were presented at the Interdisciplinary Summer Workshop of the Eighth Berlin Program for Advanced German and European Studies in June 2019 at the Freie Universität Berlin and the “Europe on the Rocks” series in November 2019 at Bryn Mawr College. I want to thank in particular Jeffery Johnson, Martin Rosenstock, Joachim Wintzer, and Gene McGarry for their helpful input. The peer reviewers of the journal have provided extremely insightful comments and suggestions in getting the essay to its current shape.

Works Cited

“550.000 abgelehnte Asylbewerber leben in Deutschland – Pro Asyl verhindert Rückführung ‘systematisch.’” September 22, 2016, https://www.epochtimes.de/politik/deutschland/550-000-abgelehnte-asylbewerber-leben-in-deutschland-pro-asyl-verhindert-rueckfuehrung-systematisch-a1358872.html

“65,600,000 Refugees Expect Acceptance and Integration.” The People’s Daily, June 22, 2017, https://kknews.cc/world/4m3kxmg.html

“About Yao Chen.” UNHCR USA website, https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/yao-chen.html

Alexander, Robin. Die Getriebenen: Merkel und die Flüchtlingspolitik. Report aus dem Innern der Macht. Munich: Siedler Verlag, 2017.

“Amnesty-Index. In China und Deutschland sind Flüchtlinge besonders willkommen.” Spiegel, May 19, 2016, https://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/amnesty-international-index-wo-fluechtlinge-besonders-willkommen-sind-a-1092990.html

“Central Committee of the Communist Youth League of China Article: Should China Accept Refugees?” 共青团中央刊文: 中国应不应该接收难民? CYLC共青团中央, June 23, 2017, http://www.szhgh.com/Article/news/comments/2017-06-23/140647.html

“China Delivers Food Aid to Syria under the Belt and Road Initiative,” CGTN, November 21, 2017, https://news.cgtn.com/news/3263544d78637a6333566d54/share_p.html

“China Mass Stabbing: Deadly Knife Attack in Kunming.” BBC, March 2, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-26402367

“China Plans to Admit Refugees from the Middle East. Do You Agree?” 中国要接收中东难民? 你愿意吗?” Sohu搜狐, http://www.sohu.com/a/151447970_313480

“China: Flüchtlinge sind keine Migranten.” Tichys Einblick, July 11, 2017, https://www.tichyseinblick.de/kolumnen/aus-aller-welt/china-fluechtlinge-sind-keine-migranten/

“Chinese in Germany Are Worried about the ‘Refugee Wave,’ Saying It Will Affect Social Stability in Germany.” Nouvelles d’Europe, November 12, 2015, http://www.oushinet.com/news/qs/qsnews/20151112/211534.html

Koetse, Manya. “Chinese Netizens on World Refugee Day: ‘Don’t Come to China.’” What’s on Weibo, June 23, 2017, https://www.whatsonweibo.com/chinese-netizens-world-refugee-day-dont-come-china/

“Chinese Students Abroad: Germany, Stricken by Refugee Sexual Assault, Is No Longer A Safe Country.” 中国留学生:被难民性侵笼罩的德国已不再是一个安全的国度. December 12, 2016, https://www.sohu.com/a/121365922_522913

Chung, Chien-peng. “China’s ‘War on Terror’: September 11 and Uighur Separatism.” Foreign Affairs 81.4 (2002): 8–12.

“Condition of Hong Kong victim of train axe attack improves.” Hong Kong Free Press, July 22, 2016, https://www.hongkongfp.com/2016/07/22/condition-of-hong-kong-victim-of-train-axe-attack-improves-germany-to-provide-hk340k-emergency-funds/

“Contributions to UNHCR – 2017.” UNHCR website, February 14, 2018, https://www.unhcr.org/5954c4257.pdf

Craft, Lucy. “Dozens of immigrant detainees on hunger strike in Japan to protest harsh conditions.” CBS News, October 3, 2019, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/japan-dozens-of-immigrant-detainees-on-hunger-strike-protest-harsh-conditions/

Dassen, Marc. “A Hidden and Filthy Refugee Industry in Germany.” 隐秘而龌龊的德国难民产业链. September 7, 2015, http://www.dooc.cc/2015/09/38599.shtml

Dassen, Marc. “Asylindustrie: Wer macht den Reibach? COMPACT klopft den Profiteuren auf die Finger!” Elsässers Blog, https://juergenelsaesser.wordpress.com/2014/11/28/asylindustrie-wer-macht-den-reibach-compact-klopft-den-profiteuren-auf-die-finger/

Delfs, Arne, and Patrick Donahue. “Merkel Seeks China’s Help on Refugee Crisis She Can’t Escape.” Bloomberg.com, October 29, 2015, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-10-29/merkel-seeks-china-s-support-on-refugees-as-crisis-follows-her

“Do Germans Suffer from ‘Madonna Cancer’ by Accepting Refugees?” 德国人收留难民是患了‘圣母癌’,” QQ腾讯, September 17, 2015, https://view.news.qq.com/original/intouchtoday/n3285.html

Drzymalla, Laura Maria, Sophie Lobenhofer, and Juliane Becker. “Ranking: Wo sind Flüchtlinge besonders willkommen?” Zeitjung, n.d. https://www.zeitjung.de/fluechtlinge-laender-liste-ranking-refugeeswelcome-deutschland/

“Should Anyone Dare to Advocate Hu Yaobang’s Ethnic Policies?” 竟然鼓吹胡耀邦的民族政策? Red Culture Net红色文化网, July 8, 2013, http://www.hswh.org.cn/wzzx/llyd/ls/2013-07-08/21683.html

Gao, Charlotte. “Why China Wants Syria in its New Belt and Road.” Diplomat, November 30, 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/why-china-wants-syria-in-its-new-belt-and-road/

“Germany Has So Many Refugees; Will It Affect the Quality of Life?” 德国难民那么多, 会影响生活体验吗? Comment on January 20, 2018, Zhihu知乎, https://www.zhihu.com/question/52915616

Gohel, Sajjan M. “The ‘Seventh Stage’ of Terrorism in China.” CTC Sentinel 7.11 (2014), https://ctc.usma.edu/the-seventh-stage-of-terrorism-in-china/

Graw, Ansgar. “Migration: Abgeordnete warnen vor einem ‘neuen Budapest.” Welt, November 11, 2019, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article203336644/Migration-Abgeordnete-warnen-vor-einem-neuen-Budapest.html

Halloran, Terry J. “Ten Facts about Refugees in China.” The Borgen Project, October 1, 2016, https://borgenproject.org/ten-facts-about-refugees-in-china/

“Has China Accepted Refugees Before? What Does Neighboring Vietnam Think? Wang Zhi’an Chastises Chinese for Not Loving Refugees; This Opinion Is Stupid.” 中国接受过难民吗邻国越南如何看王志安怒批中国不爱难民言论很傻冒. Shaibaonet筛宝网, April 5, 2019, https://www.shaibaonet.com/wangshirizhi/9378.html

He, Huifeng. “Forgotten Stories of the Great Escape to Hong Kong across the Shenzhen Border.” South China Morning Post, January 13, 2013, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1126786/forgotten-stories-huge-escape-hong-kong

He, Qinglian何清涟. “Germany’s Drama: ‘Political Correctness’ Is More Important than National Security.” 德国的戏剧: “政治正确”高于国家安全. VOA, January 10, 2016, https://www.voachinese.com/a/he-germany-20160109/3138703.html

————. “Germany’s Drama: How Merkel Ruined Germany’s Future.” 德国的戏剧: 默克尔如何毁掉德国的未来. September 26, 2016, https://www.voachinese.com/a/heqinglian-blog-german-future-20160926/3524932.html

————. “Germany’s Drama: Merkel’s Refugee Policy Quietly Turned.” 德国的戏剧: 默克尔难民政策悄然转身. February 10, 2017, https://heqinglian.net/2017/02/10/german-immigrants-policy/

————. “Germany’s Drama: Public Opinion as the Foundation of Merkel’s Throne.” 德国的戏剧: 默克尔王座下的民意基础. VOA, September 25, 2016, https://www.voachinese.com/a/heqinglian-blog-german-politics-20160925/3524018.html

Herreria, Carla. “Website Removes Racist ‘Save A Dog, Eat A Chinese’ T-Shirts.” Huffington Post, March 7, 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/save-a-dog-eat-a-chinese-shirt_n_58bf34dfe4b0d1078ca1fe55

Hille, Peter. “Platz für Flüchtlinge in Deutschland?” DW, March 6, 2020, https://www.dw.com/de/platz-f%C3%BCr-fl%C3%BCchtlinge-in-deutschland-seebr%C3%BCcke-sicherer-hafen/a-52659177

Hirst, Stephen K. “South Korea Shuts the Gates.” Slate, December 4, 2018, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2018/12/yemen-refugees-south-korea-jeju-island.html

“History Warns China: Be Cautious about the Middle East Refugee Question.” 历史警告中国:谨慎面对中东难民问题. Duowei News多维新闻, June 25, 2017, http://culture.dwnews.com/history/news/2017-06-22/59821567.html

“Hong Kong victim of brutal German train attack wakes from coma, but condition still severe.” South China Morning Post, August 20, 2016, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-crime/article/2006306/hong-kong-victim-brutal-german-train-attack-wakes-coma

“How Has He Qinglian Demonized Merkel? Her Various Deceptive Arguments.” 何清涟怎样妖魔化默克尔?— 其欺骗性逻辑种种. Wenxuecity, March 30, 2017, http://blog.creaders.net/u/4775/201807/326266.html

Hu, Wenhui胡文辉. “Knowing the History of the Suffering of Chinese Immigrants, Will You Still Feel Rejecting Refugees Is Justified?” 知道了华人移民受难史, 你还会觉得拒绝难民理所应当吗?” QQ, December 5, 2016, http://dajia.qq.com/original/category/hwh20161205.html

Huang, Rihan黄日涵, and Li Congyu 李丛宇. “The European Refugee Crisis and Its Responses from the Perspective of International Migration.” 国际移民视角下的欧洲难民危机及其应对. Shanghai Research Institute of International Affairs, Nov 15, 2017, http://www.siis.org.cn/UploadFiles/file/20171115/201705005%20%20%E9%BB%84%E6%97%A5%E6%B6%B5.pdf

“Hu Yaobang’s Xinjiang Policy.” 胡耀邦的新疆政策, BBC, June 2, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/comments_on_china/2014/06/140602_coc_huyaobang_xinjiang_policy

“Internet Rumor That China Is Going to Accept Refugees Causes Panic among Netizens.” 网传中国将接受难民 引发网民恐慌. Boxun博讯, June 23, 2017, https://boxun.com/news/gb/china/2017/06/201706231827.shtml

“Japan Rejected over 99% of Refugees Last Year. Here’s Why.” February 17, 2017, https://youtu.be/m_7dGLLL0ew

“Japan Says It Must Look after Its Own before Allowing in Syrian Refugees.” Guardian, September 30, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/30/japan-says-it-must-look-after-its-own-before-allowing-syrian-refugees-in

“Japan: ‘No One Is Illegal’ – Protesters Welcome Refugees in Tokyo.” YouTube, March 26, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ASEt-mpCrGA

“Jiny Lan, a Famous and Formidable Chinese Female Painter in Germany: From ‘Poster Girl’ to Interfering in European Politics.” 德国有名也要命的华人女画家蓝镜:从“海报女郎”到干预欧洲政治.” Chinesische Handelzeitung华商报, April 16, 2019, http://huashangbao.com/2019/04/16/%E5%BE%B7%E5%9B%BD%E6%9C%89%E5%90%8D%E4%B9%9F%E8%A6%81%E5%91%BD%E7%9A%84%E5%8D%8E%E4%BA%BA%E5%A5%B3%E7%94%BB%E5%AE%B6%E8%93%9D%E9%95%9C%EF%BC%9A%E4%BB%8E%E6%B5%B7%E6%8A%A5%E5%A5%B3%E9%83%8E/

Khoo, Isabelle. “‘Save A Dog, Eat A Chinese’ T-Shirt Is A Disgusting Display of Racism.” Huffington Post, March 13, 2017, https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2017/03/13/save-a-dog-eat-a-chinese-t-shirt_n_15334860.html

Lee, Shin-wha. “South Korea’s Refugee Policies: National and Human Security Perspectives.” in Human Security and Cross-Border Cooperation in East Asia (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 227–248, doi:1007/978-3-319-95240-6_11

“Let Germany Tell Yao Chen What Becomes of Standing Together with Extremist Refugees.” 让德国告诉姚晨, 和那些极端难民站在一起的下场, Wenxuecity文学城, June 23, 2017, https://www.wenxuecity.com/blog/201706/71665/23876.html

Li, Yu李鱼, “Anti-Refugee Sentiment Rocks China, Goodwill Ambassador Yao Chen Was Shouted Down by Insults.” 反难民情绪激荡中国 亲善大使姚晨受辱骂. DW, June 26, 2017,https://www.dw.com/zh/%E5%8F%8D%E9%9A%BE%E6%B0%91%E6%83%85%E7%BB%AA%E6%BF%80%E8%8D%A1%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD-%E4%BA%B2%E5%96%84%E5%A4%A7%E4%BD%BF%E5%A7%9A%E6%99%A8%E5%8F%97%E8%BE%B1%E9%AA%82/a-39418053

Liang, Pan, “Why China Isn’t Hosting Syrian Refugees.” Foreign Policy, February 26, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/02/26/china-host-syrian-islam-refugee-crisis-migrant/

“Libya Conflict: Reactions around the World.” Guardian, March 30, 2011, https://www.theguardian

.com/world/2011/mar/30/libya-conflict-reactions-world

“Man Jailed for 11 years for Rape of Two Chinese Students.” The Local, May 16, 2017, https://www.thelocal.de/20170516/man-jailed-for-11-years-for-rape-of-two-chinese-students

“Man Sentenced to Life in Prison for Rape and Murder of Chinese Student, The Local, August 4, 2017, https://www.thelocal.de/20170804/man-sentenced-to-life-in-prison-for-rape-and-murder-of-chinese-student

McCurry, Justin. “Japan Had 20,000 Applications for Asylum in 2017. It Accepted 20.” Guardian, February 15, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/16/japan-asylum-applications-2017-accepted-20

“Merkel erfolgreich in China: Hilfe in der Flüchtlingskrise und Milliardenverträge.” Abendzeitung München, October 29, 2015, https://www.abendzeitung-muenchen.de/inhalt.merkel-erfolgreich-in-china-hilfe-in-der-fluechtlingskrise-und-milliardenvertraege.92a1f296-1516-4060-b578-51203c66ba55.html

Murai, Shusuke. “Japan recognizes only 27 refugees, despite rising numbers of applications.” Japan Times, January 23, 2016, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/01/23/national/social-issues/japan-recognizes-27-refugees-despite-rising-numbers-applications/#.Xe6aD-hKg2w

Newhouse, Sean. “Who is UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador Yao Chen?” The Borgen Project, July 29, 2017, https://borgenproject.org/unchr-goodwill-ambassador-yao-chen/

“No Entry: How Japan’s shockingly low refugee intake is shaped by the paradox of isolation, a demographic time bomb, and the fear of North Korea.” Business Insider, April 11, 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/why-japan-accepts-so-few-refugees-2018-4

“Not Welcome: Japan Refuses More Than 99 Percent of Refugee Applications.” Telegraph, May 4, 2017, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/05/04/not-welcome-japan-refuses-99-percent-refugee-applications/

Ostrand, Nicole. “The Syrian Refugee Crisis: A Comparison of Responses by Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 3.3 (2015): 255–279.

Park, S. Nathan. “South Korea Is Going Crazy Over a Handful of Refugees: Feminists, the young, and Islamophobes have allied against desperate Yemenis.” Foreign Policy, August 6, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/08/06/south-korea-is-going-crazy-over-a-handful-of-refugees/

“Pressekonferenz von Bundeskanzlerin Merkel und dem Ministerpräsidenten der Volksrepublik China, Li Keqiang in Peking.” Mitschrift Pressekonferenz, October 29, 2015, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/pressekonferenzen/pressekonferenz-von-bundeskanzlerin-merkel-und-dem-ministerpraesidenten-der-volksrepublik-china-li-keqiang-843086

“Refugee Welcome Survey 2016 – The Results.” Amnesty International, May 19, 2016, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/05/refugees-welcome-survey-results-2016/

“Refugees Flooded into Europe. What Do Local Chinese Think?” 难民涌入欧洲,当地华人怎么看? Xinhuanet新华网, September 18, 2015, http://www.xinhuanet.com/world/2015-09/18/c_128244603_4.htm

Ren, Mu. “Interpreting China’s (Non-)Intervention Policy to the Syrian Crisis: A Neoclassical Realist Analysis.” Ritsumeikan University International Studies 立命馆国際研究, 27.1 (June 2014): 259–281.

Rich, Timothy S., and Kaitlyn Bison. “Answering the question: should South Korea accept refugees?” The Interpreter, December 14, 2018, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/answering-question-should-south-korea-accept-refugees

Riegert, Bernd. “EU-Flüchtlingspolitik: 2020 ist nicht 2015.” DW, March 3, 2020. https://www.dw.com/de/eu-fl%C3%BCchtlingspolitik-2020-ist-nicht-2015/a-52623823

Rudolf, Moritz, and Angela Stanzel. “China Should Do More to Solve the Syrian Refugee Crisis.” Diplomat, February 2, 2016, https://thediplomat.com/2016/02/china-should-do-more-to-solve-to-syrian-refugee-crisis/

Shi, Jiangtao, “China willing to open its pockets, but not borders, to Middle East refugees.” South China Morning Post, June 26, 2017, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2099908/china-willing-open-its-pockets-not-borders-middle-east

“Shoot Yourself in the Foot and You Have Only Yourself to Blame—Congratulations to Germany for Producing a Female Hu Yaobang, the Kind of Great Person Who Occurs Once in Ten Thousand Years.” 搬起石头砸自己的脚, 咎由自取 – 祝贺德国出了个女胡耀邦, 不愧万年一出的伟人啊. Wenxuecity, September 20, 2016, https://bbs.wenxuecity.com/currentevent/866698.html

“Should China Accept Middle Eastern Refugees? 90% of Residents Are Vehemently Opposed.” 中国应否接收中东难民 九成民众激烈反对. Aboluo News阿波罗新闻网, June 23, 2017, https://www.aboluowang.com/2017/0623/950672.html

Song, Lili. “China and the International Refugee Protection Regime: Past, Present, and Potentials.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 37.2 (2018): 139–161, https://academic.oup.com/rsq/article/37/2/139/4934135

Song, Quancheng宋全成. “The European Refugee Crisis: An Analysis of Its Structure, Cause, and Impact.” 欧洲难民危机: 结构, 成因及影响分析. Chinese Social Sciences Net 中国社会科学网, Issue 20153 (2015),http://www.cssn.cn/zzx/gjzzx_zzx/201605/t20160530_3028493.shtml

Steinbeis, Maximilian, and Stephan Detjen, Die Zauberlehrlinge: Der Streit um die Flüchtlingspolitik und der Mythos vom Rechtsbruch. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta Verlag, 2019.

Steiner, Michael. “Chinesen wollen keine Flüchtlinge aufnehmen.” Contra Magazin, July 13, 2017, https://www.contra-magazin.com/2017/07/chinesen-wollen-keine-fluechtlinge-aufnehmen/

“Sweden under the Scourge of the White Left.” 白左祸害下的瑞典. Wenxuecity, May 18, 2019, https://bbs.wenxuecity.com/currentevent/1739242.html

Tanner, Murray Scot, with James Bellacqua, “China’s Response to Terrorism.” June 2016, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/Chinas%20Response%20to%20Terrorism_CNA061616.pdf

“The Chinese Arrogantly Refused to Accept Refugees; the Germans Heard and Went Nuts; China Became an Instant Role Model for the German Right-Wing, which is Raving about the Chinese.” 中国人霸气拒绝接受难民,德国人闻讯炸锅了,短时间中国成为德国右翼的榜样狂赞中国人. BackChina 倍可亲, July 15, 2017, https://www.backchina.com/blog/346973/article-276621.html

“The European Response to the Refugee Crisis and Its Lessons for China.” 难民危机的欧洲应对及其对中国的影响与借鉴. International Migration国际移民, December 17, 2018, https://www.pishu.cn/gjym/gymdt/zjjd/527865.shtml

UNHCR, Global Trends 2015. Geneva: UNHCR, 2016.

“UNHCR Asylum Trends 2013.” UNHCR website, https://www.unhcr.org/5329b15a9.pdf

UNHCR Weibo post, June 20, 2017, https://m.weibo.cn/status/4120809063158935?mblogid=4120809063158935&luicode=20000061&lfid=4120809063158935

Wang, Fan 王凡. “The Refugee Problem—Chinese in Germany Feel It Is Unfair to Germany.” 难民问题—“留德华”替德国抱不平? DW, September 9, 2015, https://www.dw.com/zh/%E9%9A%BE%E6%B0%91%E9%97%AE%E9%A2%98%E7%95%99%E5%BE%B7%E5%8D%8E%E6%9B%BF%E5%BE%B7%E5%9B%BD%E6%8A%B1%E4%B8%8D%E5%B9%B3/a-18703074

Wang, Jin. “Why Do Chinese Reject Middle Eastern Refugees?” Diplomat, June 23, 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/06/why-do-chinese-reject-middle-eastern-refugees/

Wayne, Martin I. China’s War on Terrorism: Counter-Insurgency, Politics, and Internal Security. London: Routledge, 2008.

“What’s Wrong with ‘Standing with Refugees’? Should China Accept Refugees?” 与‘难民站在一起’怎么了 中国到底应不应该接收难民? Zhihu 知乎, June 22, 2017, https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/27512778

“Where the Rubber Meets the ‘Belt and Road’ – German Ambassador Answers the Big Questions.” South China Morning Post, May 13, 2017, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2093707/german-ambassador-answers-belt-and-road-questions

“Why Do Chinese Dislike Refugees So Much?” 中国人为什么那么讨厌难民? Earth Daily地球日报, August 16, 2018, https://news.sina.cn/global/szzx/2018-08-16/detail-ihhvciiv7188436.d.html?oid=3793920787897581&vt=4

“Why is Sweden More and More ‘Dangerous?’” 瑞典怎么越来越‘危险’了? QQ, September 17, 2019, https://wxn.qq.com/cmsid/20180917B0RG0U00

“Why Scolding ‘Virgin Marys’ and the ‘White Left’ is ‘Politically Correct’ in China.” 为什么骂 “圣母”和“白左”在中国是“政治正确”的. Douban豆瓣, October 22, 2015, https://www.douban.com/note/521727464/

“Why Was Germany Willing to Accept So Many Refugees?” 德国为何愿意接受那么多难民? October 2, 2018, http://blog.creaders.net/u/5568/201810/331732.html

Xie, Fei谢菲. “The T-shirt Design that Hurts Dogs and the Chinese.” 让 ‘狗和华人都躺枪’ 的T恤衫图案. DW, March 10, 2017, https://www.dw.com/zh/%E8%AE%A9%E7%8B%97%E5%92%8C%E5%8D%8E%E4%BA%BA%E9%83%BD%E8%BA%BA%E6%9E%AA%E7%9A%84t%E6%81%A4%E8%A1%AB%E5%9B%BE%E6%A1%88/a-37868454

Yu, Han雨涵. “No Longer Feeling Secure: Chinese in Germany Concerned about Safety.” 安全感不再: 在德华人忧心治安. December 7, 2016, https://www.dw.com/zh/%E5%AE%89%E5%85%A8%E6%84%9F%E4%B8%8D%E5%86%8D%E5%9C%A8%E5%BE%B7%E5%8D%8E%E4%BA%BA%E5%BF%A7%E5%BF%83%E6%B2%BB%E5%AE%89/a-36677214

Zeng, Yu 曾宇. “What Role Can China Play in Responding to the International Refugee Crisis?” 中国可以在应对国际难民危机中扮演什么角色? Sohu News搜狐新闻, November 9, 2015, https://news.sohu.com/20151109/n425702063.shtml

Zhan, Hao占豪. “Those Who Suggest or Indicate China Should Admit Middle Eastern Refugees Should Be Condemned” 建议或暗示中国引入中东难民者,其心当诛! Observer Net 察网, June 22, 2017, http://www.cwzg.cn/politics/201706/36727.html

Zhang, Danhong 张丹红. “Germany Gossip—Merkel or Cixi.” 闲话德国:默克尔还是慈禧. DW, March 26, 2018, https://www.dw.com/zh/%E9%97%B2%E8%AF%9D%E5%BE%B7%E5%9B%BD%E9%BB%98%E5%85%8B%E5%B0%94%E8%BF%98%E6%98%AF%E6%85%88%E7%A6%A7/a-43101961

————. “Mein Deutschland: Zwei Provokateure und ein Merkel-Portrait.” DW, March 23, 2018, https://www.dw.com/de/mein-deutschland-zwei-provokateure-und-ein-merkel-portrait/a-43064523

Zhao, Yashan赵雅珊. “Observation: Vicious Incidents Happen Frequently in Germany; Local Chinese Feel All Kinds of Feelings.” 观察:德国恶性事件频发 华人感受五味陈杂. BBC, July 30, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/world/2016/07/160730_ana_germay_attck_china_reax

[1] All translations are my own, and all websites were accessed on March 8, 2020, unless otherwise noted.

[2] I thank the artist, who sent me this note on August 7, 2020, after reading my article. Jiny Lan is a founding member of the “Bald Girls,” the first feminist artists’ group in China; see “Jiny Lan,” https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jiny_Lan; Didi Kirsten Tatlow, “In Art, a Strong Voice for Chinese Women,” The New York Times, March 7, 2012. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/08/world/asia/08iht-letter08.html. Accessed on August 9, 2020.

[3] In her note to me on August 7, 2020, the artist also revealed a second layer of meaning behind her choice of Cixi. As one of the few women artists in China who publicly identifies herself as a feminist, she holds a view of Cixi that differs from how she is commonly portrayed in history books. In her painting series ‘His Story,’ she challenges the judgment of Cixi by historians, the vast majority of whom have been male. In her artwork “Collective Efforts” from 2012, Lan demonstrates her feminist stance even more clearly, questioning whether it was right to lump most of the responsibility for the Cultural Revolution onto Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing. She also transfers that sympathy for women in power to Frau Merkel: Would the chancellor suffer the same fate? Yet, with respect to Merkel’s refugee policy, Lan maintains her skepticism.

[4] Yao Chen is a mainland celebrity who dedicated herself to the refugee cause. She began working with the UNHCR in 2010 and officially became China’s first Goodwill Ambassador to the UNHCR in 2013. She had over 80 million Weibo followers, equivalent to Germany’s entire population, and she used her influence to bring attention to refugees and to encourage donations from China to UNHCR. For example, between 2012 and 2013, donations tripled from mainland China. Her appointment was renewed in 2017 for another two years. “About Yao Chen,” UNHCR USA website.

[5] Li, “Anti-Refugee Sentiment Rocks China”. The article falsely states that the city of Yiwu in Zhejiang issued temporary residence permits to 9,675 foreigners in 2016, half of them from Iraq, Yemen, Syria, and Afghanistan.

[6] Because of the global reach of the internet, it is not always possible to distinguish whether they were posting from the mainland or overseas or both.

[7] Hu, “Knowing the History of the Suffering of Chinese Immigrants.” He also referred to the recent rap video “Meet the Flockers” by the African-American rapper YG. The song advocated robbing Chinese Americans, which provoked protest marches by Chinese in Philadelphia and created racial tensions between African Americans and Chinese Americans.