Spoofing Herzog and Herzog Spoofing

Eric Ames

Abstract:

This essay explores how humor, parody, and self-parody have shaped and reshaped the public image of the filmmaker Werner Herzog, especially since the 1990s and with the help of various spectators, particularly those who create and circulate their own images of the iconic German director. To see this dynamic at work, we have to look not only at Herzog’s films, but also at his many interviews and public appearances, at his performances in films made by other directors, at animated cartoons and reality TV programs, at Internet blogs and streaming videos, at comedy websites and live-comedy shows. Collectively, this material suggests that the revitalization of Herzog’s career in recent years has relied in part on humor and parody: that of the filmmaker and that of his audience.

Acknowledgements:

This article was originally written for Lektionen in Herzog: Neues über Deutschlands verlorenen Filmautor und sein Werk, edited by Chris Wahl and forthcoming with Text + Kritik (Munich), the first scholarly book on Herzog to be published in Germany in more than 30 years. The author wishes to thank the editor and the publisher for permission to reproduce this article here.

In the upcoming season of The Boondocks, the animated comedy series about an African-American family that moves from the South Side of Chicago to the imaginary suburb of Woodcrest, one episode takes the form of a documentary news program made for German television. Filled with excitement for Barack Obama’s victory, a German reporter travels to Woodcrest, presumably to interview locals about the U.S. presidential election. The cartoon reporter is not only named Werner Herzog and illustrated to resemble him. The character is voiced by Herzog himself. At the present writing, the episode is still in production, but even so it points to the many existing Herzog parodies and self-parodies that are the subject of this essay.1

Herzog is an easy target of parody, not least because he insistently projects an exaggerated self-image of unbending, one-sided seriousness. Consider the following statement of his: “I am someone who takes everything very literally. I simply do not understand irony,” a claim he has made for decades now.2 How are we supposed to take this claim, literally or figuratively? The very status of such extreme literalness is unclear. What is clear, however, is that both elements – his supposed lack of irony and the gloomy seriousness he exudes in making this claim – play into existing stereotypes about German identity and about the German filmmaker in particular. Herzog is not just aware of these stereotypes.3 Over time, he has developed certain strategies for appropriating and refunctioning them. In this essay, I want to concentrate on his use of parody and self-parody. I understand parody as a particular mode of intertextuality, based on imitation and transformation, which generates multiple (and sometimes conflicting) meanings, and does so primarily (but not exclusively) for humorous effect. Parody of course has a deeply ambivalent relationship to its target – a relationship that only becomes more explicit in the case of self-parody, where the source of humorous effect is less the disparagement of a model than the attempt at self-imitation.4

The key terms of my discussion – parody and self-parody – can be illustrated by a scene from Herzog’s film My Best Fiend (Mein liebster Feind, 1999). The title itself announces the film’s ambivalent relationship to its subject. My Best Fiend pays tribute to the late German actor Klaus Kinski, who was – and remains – best known for his performances in Herzog’s films Aguirre (1972), Nosferatu (1978), Woyzeck (1979), Fitzcarraldo (1982), and Cobra Verde (1987). These very productions established Herzog’s international reputation as both a “master” filmmaker and a “megalomaniac,” one whose work characteristically portrays men of supposed genius and madness – as exemplified not least by Herzog and Kinski themselves. Their artistic relationship is legendary (in every sense of the word). At one point during the production of Aguirre, for instance, Herzog supposedly directed Kinski by training rifle on him from behind the camera. During the same production, each was simultaneously planning to murder the other. I’m not interested in the veracity of such material. All that matters here is its relational structure. From this perspective, My Best Fiend represents a cinematic self-portrait of the filmmaker as routed through his love-hate relationship with the actor. Throughout the film, Herzog himself frequently appears onscreen, either interviewing people or addressing the camera directly. In this regard, perhaps the most telling strategy he employs is that of impersonation.

In the first scene proper, Herzog returns to the Munich boarding house where he lived as a teenager along with his mother, brothers, and eight other occupants, including for a time Kinski. What was once a low-grade pension is now a richly appointed house, owned and inhabited by a baron and a baroness, whose visibly uncomfortable presence onscreen becomes part of the scene’s humor and appeal. Herzog takes the couple on a guided tour of their own home as it appeared when he and Kinski lived there. Along the way, he plays not only the role of tour guide, but also that of himself as the director of a documentary, that of his younger self as historical witness, and that of the absent Kinski. The camerawork alternates between medium close-ups of Herzog and wider shots to show the couple’s reaction. Throughout this scene he plays for a double audience: we observe the baron and the baroness, who listen and watch – eyes wide, cheeks flushed – as Herzog recounts a series of increasingly bizarre and socially inappropriate stories.5 Indeed, the filmmaker gives a vivid description of the domestic interior as it had been earlier, only to verbally defile and demolish it, room by room. He begins in what is now a sparkling white guest room, where he and his entire family once lived “in some poverty.” The tour gains momentum when he enters the adjacent bathroom. In his words, “Kinski locked himself in this bathroom for two days and two nights … and, in a maniacal fury, smashed everything to smithereens.” Moving on, Herzog shows the couple where Kinski once slept, outlining with his hands a “tiny closet” in what is now their spacious kitchen. On one occasion, he recalls, Kinski became so upset that his shirt collars had not been properly ironed by his landlady that he burst out of his room, knocked down an interior door, and landed in her room, literally foaming at the mouth and screaming at the top of his lungs, “You stupid pig!” Here and elsewhere in the film, Herzog mimics the voice and manner of Kinski. It is a subdued performance, to be sure, one that juxtaposes the crudeness of the material with the control of its retelling. Rather than scream as Kinski had, for example, Herzog speaks in a hushed voice, squints his eyes, and shakes his fists in the air. At the same time, the scatological aspects of Kinski’s language and behavior allow Herzog to give a physical performance of his own. The act of impersonation does more than just evoke an absent person; it opens up a space for humor and parody by means of juxtaposition. As if to underscore this very move, the scene closes with a sound recording of Kinski reciting a poem about “dog shit” and “monkey piss” as the camera slowly pans across the kitchen.

My Best Fiend illustrates some of the defining characteristics of parody as I engage it throughout this material: most notably, its formal ambivalence – that is, its complex structure, which imitates and thereby integrates the very object of parody; its multiple effects, ranging beyond mere ridicule to include homage, affection, contempt, fascination, admiration, playfulness, and so on; finally, its dual impulse to destroy and preserve its sources, or what is often described as “the paradox of parody.”6 In this case, Herzog not only has the proverbial last word on Kinski; the director also reasserts his own persona and his own films as cultural reference points in the present.

What makes this example particularly useful for the present discussion is that My Best Fiend may be the only Herzog film that the Germans have ever liked. When it premiered in 1999, German commentators focused on the film’s unexpected humor, especially in those places where the anecdotes being retold seemed to confirm received ideas about each extraordinary figure.7 The same commentators just assumed a certain naiveté on Herzog’s part, a discrepancy between the presumed intention and the resulting effect, which made the film even funnier for them.8 Although I don’t share in this assumption, as should be clear, I do want to use it as a point of departure, because it sets in relief the very different image of Herzog that emerges when we turn to other contexts – sites where the director and his films have not been virtually forgotten, as they have in Germany, but have instead become a source of enduring fascination and aesthetic enjoyment. When Herzog speaks at international film festivals or at retrospectives of his work – events that have been videotaped and posted on the Internet – what is most remarkable is not what he says, but rather his interaction with the audience and its resounding laughter.9

As I argue, although they have yet to be addressed in the scholarship, humor and parody have both revised and reinforced the established image of Herzog, while at the same time making what amounts to a bid for the continued visibility and relevance of his films in a rapidly changing media landscape. To see this dynamic at work, we have to look not only at his films, but also at his many interviews and public appearances, at his performances in films made by other directors, at animated cartoons and reality TV programs, at Internet blogs and streaming videos, at comedy websites and live-comedy shows. Bringing together such diverse material requires a methodological caveat: that is, we need to think about parody “not as a single and tightly definable genre or practice, but as a range of cultural practices which are all more or less parodic.”10

Self-Display, Self-Parody, and Media Archaeology

Since the late 1990s, although he has continued to project an aura of self-important seriousness, Herzog has engaged as never before in conspicuous acts of play and self-parody. This is especially true of his performances in the films of Zak Penn: namely, Incident at Loch Ness (2004) and The Grand (2007). In each case, Herzog’s self-display refers beyond the film’s diegetic universe to summon his own cinematic past, while rehearsing and revising it in the present. Self-display too offers a timely way of appearing before and appealing to a new generation of spectators. Paradoxically, acting both liberates Herzog from his supposed lack of irony, and allows him to continue making that very claim in the context of his own films.

The Grand provides one example. A comedy about the world of professional poker, it consists of mostly improvised performances from a stellar lineup of American actors and comedians: Woody Harrelson, Ray Romano, Jason Alexander, and others. The wildcard here is Herzog. For him, the film becomes a chance to send up some of the stereotypical images that have attached to his public figure, while drawing on the black humor that runs throughout his work. In this case, he plays a notorious gambler called simply “The German.” In order “to feel alive,” The German explains, he “must kill something each day.” Wherever he goes – and he travels around the world, “literally everywhere,” he says – The German brings with him a small menagerie of unwitting victims: cats, goats, rabbits, and rodents. Inside the hotel, where the poker tournament is being held, an employee informs The German that animals are strictly forbidden, to which he replies: “Don’t worry. They won’t be here very long.” Herzog’s performance is equally brief and deadpan. It draws on a caricature of the strange, evil-doing German who will stop at nothing to get what he wants. This is also a caricature of the filmmaker himself, one that critics have long used against him – “playing the German card,” if you will. Herzog simply turns the table on his critics by playing the German card himself. He literally embodies what is already grotesque, an extreme form of exaggeration, which makes his self-image monstrous.

The more extensive and complex example of self-parody is Incident at Loch Ness. The first thing that needs to be said about this film is that its narrative structure is deliberately confusing. It involves multiple films within films, creating a mise-en-abyme situation that is further complicated by hoaxing on every level.11 The aspect of genre is equally shifty. For instance, the film makes truth claims in the mode of documentary (especially through the use of participant testimony), while at the same time rewarding savvy viewers for identifying signs of hoaxing and fabrication.12 Complicating matters even more was the revelation, shortly before the film’s release in 2004, that an accident on the set had resulted in the death of two crew members, which the producers then concealed to avoid litigation. The news appeared on a website called “The Truth about Loch Ness,” posted by a disgruntled member of Herzog’s crew. The revelation turned out to be bogus, the website another hoax.

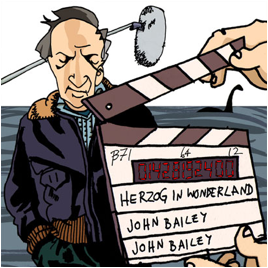

For the purpose of my discussion, here is what one needs to know about the story: All the characters appear “as themselves.” For his part, Herzog participates in what are ostensibly two different projects. The resulting film, Incident at Loch Ness, presents itself as based on footage from both projects. One of them, directed by John Bailey, is a documentary called “Herzog in Wonderland.” It began, we are told, as a portrait of the German filmmaker at work behind the scenes. As the title suggests, however, the project soon descends into a fantasy world of strange creatures and mysterious happenings. The other film project is called “The Enigma of Loch Ness.” It is produced by Zak Penn and directed by Herzog. This one, however, turns out to be a deception, a ruse designed to co-opt the famous director and his credibility for the sake of producing a Hollywood-style commercial movie, complete with special effects and a centerfold model.

Upon realizing that he has been duped, so the story goes, Herzog finds himself (once again) on a production spinning out of control. Here is a clip from the film that encapsulates this predicament and provides a good example of Herzog’s self-display.

http://blip.tv/transitjournal/loch-ness-clip-4148913

Clip 1: “Worst production ever,” from Incident at Loch Ness (U.S., 2004; dir. Zak Penn).

For those viewers who aren’t familiar with Herzog, he is introduced at the very beginning of the film through a brief montage of his work. Much of the film’s humor, though, relies for its effect on the viewer’s familiarity with the many legends surrounding Herzog, his films, and their production. The clip, for instance, recalls not only the films that he made with Kinski, but also Herzog’s boast that, in any given film – especially those with Kinski – he could have played all the characters himself.13 Indeed, this is precisely what he ends up doing in the film. And that is not all. He fills all the technical roles too: cinematographer, sound man, and so on. Incident at Loch Ness thus creates an opportunity for Herzog to rehearse and reinforce selected moments of his own cinematic past, in effect of multiplying those moments, giving them new life and new dramatic twists.14

Herzog’s on-camera performance involves not just reenacting certain scenarios of his own cinematic past, but also – to a certain extent – demystifying them. In a later scene, he finds himself (once again) battling with Kinski on the set of Aguirre. Only now their roles are reversed, so that Herzog is the one being directed at gunpoint – trapped in the very mythical scenario that he himself had created, albeit with help from the press.

“That’s just a myth!” he exclaims, while looking down a gun barrel, only to observe that the gun isn’t even loaded. The film then cuts to an interview, in which Herzog recalls the situation with Kinski and explains it more fully. This sequence in particular demonstrates the function of parody as an “archaeology” of Herzog’s cinematic past. By that I mean it both summons up the history of his films, which provide the model for Incident at Loch Ness, and recreates the material conditions of their production.15 In commenting critically on Penn’s film, Herzog ironically foregrounds its origins in his own work. This double move also has implications for our historical understanding of Herzog’s films, for it invites us to see them not in isolation, as they are usually discussed in the scholarship, but rather in relation to other films and media forms that define our visual culture. This too is a form of demystification. Here I’m going to focus on two examples – namely, mock-documentary and reality television – but I’ll return to this point again later, from a different angle, in relation to video parodies and the Internet.

Clearly, Incident at Loch Ness belongs to the latest wave of mock-documentaries that other scholars have explored in depth. Throughout the scholarship, mockumentary is understood as raising fundamental questions about documentary and its associated claims to truth.16 Although it is nowhere mentioned in the literature, Incident at Loch Ness also contributes to this project. Suffice it to say that the expedition team includes a crypto-zoologist, who turns out to be a professional actor, only to then be knocked off the boat and devoured by the monster itself. What makes this film worth discussing, however, is how it internalizes and embodies the project of mockumentary in the figure of Herzog. Even as he pretends to be taken in by the film’s deception, Incident at Loch Ness suggests that, in a way, mockumentary is also Herzog’s modus operandi. Consider his many rants against the documentary tradition and its dogmatic sobriety, his savaging of “cinéma vérité.” Moreover, when it comes to his own documentaries, Herzog never exempts himself from deception or manipulation. On the contrary, he openly endorses staging, scripting, and invention, which in turn become the basis for his own – alternative – truth claims.17 All these claims and arguments, along with his many films and the legends of their production, trail behind Herzog as he performs his own directorial persona on camera.

In this case, the entire production relies on Herzog to bring with him a distinctive mix of celebrity and credibility. The presence of the well-known filmmaker would seem to authenticate the fiction that is the story of Incident at Loch Ness. In a way, celebrity grants Herzog a documentary function of his own, because of his perceived connection to the world of the spectator. Not only the film’s sense of authenticity, but also much of its humor derives from his stone-faced presence on camera. And yet, the more he lends credibility to the film, the more he adds to the hoax. So the entry (or “the rabbit hole”) into this world of allusions and illusions is the director’s self-display. Addressing the camera directly and reflecting on his previous films, Herzog speaks of his own reputation for blurring the distinction between fact and fiction, and declares his interest in exploring the space between them. It is Herzog himself who introduces the interpretive problem for viewers of Incident at Loch Ness, by summoning the ambiguous status of his own work in terms of fact and fiction.

In addition to foregrounding its cinematic origins and affiliations, Incident at Loch Ness has the effect of situating Herzog and his films vis-à-vis the context of reality television. Of particular interest here are celebrity-based shows, reality-comedy hybrids, and spoof shows which play on the conventions of reality programming. One scholar has suggested that the recent spate of mock-documentaries is partly a response to the burgeoning of reality formats and the inevitable familiarity and boredom with such offerings.18

Incident at Loch Ness lends support to this idea too. Rather than parody the conventions of reality programming, however, the film plays them straight, which is totally in keeping with its status as a hoax. On another level, though – and here is the key point – reality TV can be seen as an unexpected context for some of Herzog’s work too.19 This is especially true of Grizzly Man (2005) and Herzog’s collaboration with producers at the Discovery Channel.20 What is more, reality TV has provided a discursive context for performing his own directorial persona, not only in this film, Incident at Loch Ness, but also in interviews and press conferences going back almost a decade. When asked about recent films and other materials that have influenced him, Herzog routinely mentions The Anna Nicole Show (2002-2003) and The Real Cancun (2003), a spring-break film from the producers of The Real World on MTV.21 For Herzog to recommend this material invites a laugh for several different reasons. What most interests me, however, is the affinity it suggests, however jokingly, between Herzog’s films and reality TV shows. Above all, it is the “playful, performative element” of these shows that corresponds with Herzog’s work – both in spite of its very seriousness and precisely because of it.22 This particularly holds for the documentaries such as My Best Fiend and Grizzly Man. Although they revolve around extreme conditions of existence and forms of behavior, much of our engagement with his documentaries hinges, paradoxically, on our awareness that what we are watching is also staged for the camera. Incident at Loch Ness simply takes this dynamic to the nth degree.

Herzog’s performance in Incident at Loch Ness and in The Grand indicates more than just a capacity for irony and self-reflexivity. It engages and responds to his critics; it reiterates and complicates his performance of a directorial persona; it reinforces his films and promotes their rediscovery. Indeed, Herzog’s self-display doubles as a form of audience address. It particularly appeals to younger viewers who are more or less familiar with parody and media recycling, to viewers who are accustomed not only to film, but also to reality television, to home video, and to the Internet – key areas of popular culture in which parody has become a sort of lingua franca.

Mimicry, Web Parody, and Collective Play

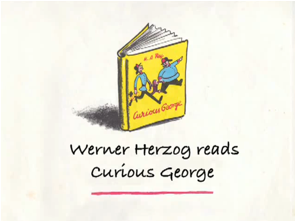

When it comes to spoofing Herzog, the target of parody tends to be his status as the iconic German filmmaker.23 This is obviously because the parodies originate not in Germany, but elsewhere – especially in the United States. Taken together, they represent a comedy of difference, which is based on deviation from the presumed cultural norm. The salient code is one of language or speech. Parodies of Herzog almost invariably mimic his trenchant, German-accented voice, or what one commentator has described as “his familiar Teutonic brogue.”24 Unlike some forms of national humor, imitating a German accent is neither troubling nor controversial. In a way, it is even cute. Hence, the recent video “Werner Herzog Reads Curious George,” which is already one in a series of videos based on the conceit of Herzog reading aloud and revising certain well-known books for children.25 The emphasis on voice is not surprising. Herzog’s vocal presence is among the most widely recognizable in all of cinema. What is remarkable, though, is how contagious this sort of mimicry can be.

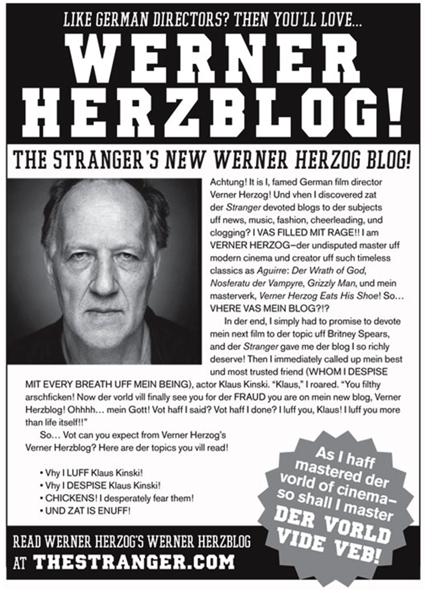

Here is a mock-advertisement from 2008 that appeared in The Stranger, a Seattle weekly, announcing that Herzog will now be blogging for the newspaper (see figure 8, next page).26 The ad begins with a rhetorical question: “Like German directors?” It features a portrait of Herzog with a grimace seemingly fixed on his face. The surrounding text puts emphasis on the voice, and is obviously meant to be read – and in an important sense heard – with a heavy German accent. The use of first-person narration is equally important to the parody, invoking and exaggerating a key expression of Herzog’s authority, while transferring that authority or “mastery” from the cinema to the Internet.27 The move itself adds to the sense of obsession that is already associated with Herzog: blogging becomes a new occasion to hold forth on the same old topics, and doing so in a blatantly unassimilated, robotic-sounding voice. Indeed, what emerges here – and throughout the Herzog parodies – is a comic image of the German filmmaker as an affectless machine, for reasons that lead back to the Bergsonian definition of laughter. In this case, what Bergson describes as “something mechanical encrusted on the living” is succinctly rendered by the term “Herzblog.”28

While the cinema provides both the occasion and the inspiration for spoofing Herzog, it is television and the Internet that provide both the “frame” through which the filmmaker and his work are parodied by others and the specific forms of parody that they tend to use: namely, blogs, home videos, web series, and reality shows. Film parodies in other media cannot be simply equated with films that borrow from earlier films; there needs to be a theoretical separation between intertextuality and transmediality. And yet the movement across media, like the act of parody, brings new perspectives and adds new meanings to the mix that defines this material.

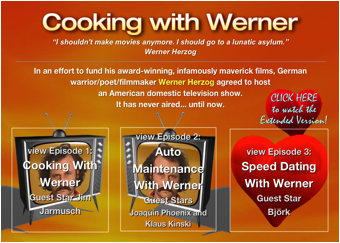

Take, for example, the web series called “Cooking with Werner.” In each episode, American comedian William Maier impersonates Herzog as the host of an American television show. The key device of parody here is the change of idiom, which is also a change in profession: from filmmaker to television host, to chef, to mechanic, and so on. In the first episode, he returns (once again) to the Peruvian jungle, only this time in search of a “special ingredient” for cooking. The series is inspired by Herzog’s performance in documentaries made by other filmmakers: above all, Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (1980) and Burden of Dreams (1982), both by Les Blank. What most interests me here is the relationship between Herzog’s performance of self and the performance of “Herzog” by others. In this regard, even more interesting than the web series is how it was initially promoted: that is, by stand-up comedy. “Werner Herzog Live Appearance” was the title of Maier’s show last fall at a Hollywood night club. The show consisted almost entirely of well-known rants and monologues by Herzog – all played straight. If the venue creates an expectation of humor and laughter, the routine and its delivery suggest how little this material needs to be changed in order to render it blatantly comic; the mere act of quotation is almost enough.29

What makes this observation even more interesting is that Herzog parodies do not only circulate via emails, blogs, Facebook pages, and comedy websites; they also appear on video-sharing sites, where they mingle indiscriminately with clips from Herzog’s many films and interviews. It is a truism in the scholarship that his work seeks to blur the distinction between fiction and documentary. What has yet to be acknowledged is that, transposed on the Internet, this very material also blurs the distinction between the serious and the comic.30

The major target and source of Herzog parodies online is the film Grizzly Man, from 2005, with several dozen videos still available on YouTube alone.31 It is worth naming some of their titles. They include “Chicken Man,” “Gopher Man,” “Hedgehog Man,” “Kitty Man,” “Sheep Man,” “Grizzly Man 2,” “Grizzly Men,” and “Grizzly Girl.”32 In their wordplay and in their literally brutal repetitiveness, the titles also indicate the rhetorical devices that the videos use for parody: namely, addition and substitution. Like most film parodies on the Internet, the preferred forms are “movie trailers,” “deleted scenes,” and “missing footage” (or “death footage,” in this case). Significantly, though, the parodies of Herzog go beyond simple remixes or mash-ups to involve more elaborate acts of staging and reenactment.33

In this regard, it is interesting to note that almost all the Grizzly Man parodies focus on the subject of Herzog’s film, Timothy Treadwell, and treat him with campy irreverence. This is an aesthetic approach, which is in no way self-evident. On the contrary, it is Herzog’s own handling of this material that makes it available to a camp sensibility. By “revealing” the staginess of Treadwell’s video persona, emphasizing both the confessional mode and the aesthetic character of his on-camera performance, Grizzly Man has the effect of inviting the film audience to regard Treadwell and others as if they were “characters” in a story.34 Underlying this move is of course Herzog’s approach to documentary filmmaking, his own penchant for staging and storytelling, and for occasionally performing himself on camera as the director of a documentary.

My signal example is “Grizzly Bear Man.” Made by a comedy duo named Travis and Jonathan, the video is available on their homepage as well as on various video-sharing and comedy websites.35 Of particular interest here is their interpretation of Herzog’s walk-on, which is one of the most memorable scenes from Grizzly Man. In the film, the scene involves an elaborate choreography of bodies, faces, gazes, and recordings. With his back to the camera, Herzog issues a series of injunctions, literally dictating to Treadwell’s ex-girlfriend what she “must never” do with the remaining sounds and images of Treadwell’s death. In the parody, the choreography of bodies becomes the stuff of travesty and slapstick. The target here is the arbitrary nature of Herzog’s authority and its abuse. In this case, the taboos become either increasingly ludicrous or sensible, depending on your perspective.

http://blip.tv/transitjournal/grizzly-bear-man-clip-4148759

Clip 2: “Grizzly Bear Man,” from www.travisandjonathan.com.

One attraction of the Grizzly Man material is the pleasure of playing a role, of acting as if one were someone or something else, whether Herzog, Treadwell, or the bear that ate him. The pleasure of such a performance is also the pleasure of a game. In this regard, there is an interesting connection between the online videos and the play of Herzog and his collaborators. The connection first appears on a parafilmic level, in DVD bonus materials. For example, the DVD for Herzog’s latest documentary, Encounters at the End of the World (2007), contains not one but supposedly two short parodies of Grizzly Man, both of which are hidden; you have to go searching for them. One is easy enough to find, but the other, an Easter-egg parody called “Seal Man,” would seem to be fictitious, a simple ruse created to promote sales.36

Even so, the uncertain activity of hide-and-seek, the pleasure in secrecy, the solving of a mystery – all this demonstrates the correspondence to games.

By the same token, the game-character of this material also develops out of parody as a playful mode of intertextuality. Here it is important to understand that the cinema of Herzog constitutes an expanding world of images, quotations, and associations, which are laid out in a way that involves the audience in a seemingly endless process of puzzling out cross-references. This is an activity that the director himself encourages when he describes his project as that of making “one big movie,” with a narrative so large and a cast of characters so vast that they cannot possibly be contained by any single film. Exploring such a world is also a form of play. In recent years, Herzog’s project has expanded even further, so that the relevant activity of spectatorship involves pursuing references not only across films, but also into the domain of new media. Parody thus becomes a way of reframing and reasserting the world of Herzog for an age of media convergence and participant culture, without either demoting or abandoning his primary stake in the medium of film.37 On another level, that of authorship, the very prospect of Herzog spoofing within the context of his own material brings us back to issues of self-parody. Indeed, all these instances of parody, self-parody, and collective play leave marks on Herzog’s style. It is no coincidence that entire passages of Encounters at the End of the World are played for humor.

Herzog’s dark humor and deadpan sensibility have endeared him to viewers in ways that critics have yet to appreciate. Parody offers a way of thinking both about the filmmaker’s self-display and about the work of viewers in producing their own content and sharing it with others. Collectively, this material suggests that the revitalization of Herzog’s career has relied in part on humor and parody: that of the filmmaker and that of his audience. The upshot is not a cinematic end point, but rather a mediated moment in the ongoing relationship between Herzog and the public. Let’s see what happens when he travels to The Boondocks.

Works Cited

Ames, Eric. “The Case of Herzog: Re-Opened.” A Companion to Werner Herzog. Ed. Brad Prager. Oxford, UK and Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, forthcoming. Print.

Bergson, Henri. Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic. 1900. Trans. Cloudesley Brereton and Fred Rothwell. New York: Macmillan, 1914. Print.

Burgess, Jean and Joshua Green. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge, UK and Malden, MA: Polity, 2009. Print.

Cheesman, Tom. “Apocalypse Nein Danke: The Fall of Werner Herzog.” Green Thought in German Culture: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Ed. Colin Riordan. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1997. 285-306. Print.

Corner, John. “Performing the Real: Documentary Diversions.” Reality TV: Remaking Television Culture. Ed. Susan Murray and Laurie Ouellette. 2d ed. New York and London: New York University Press, 2009. 44-64. Print.

Cronin, Paul, ed. Herzog on Herzog. London: Faber and Faber, 2002. Print.

Dentith, Simon. Parody. London and New York: Routledge, 2000. Print.

Duchampbuffet, Michel. “Werner Herzog as Guest Pundit on the VH1 Television Series Best Week Ever.” McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. 23 January 2008. Web. 17 January 2010. ;.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004. Print.

Fetveit, Arild. “Reality TV in the Digital Era.” Reality Squared: Televisual Discourse on the Real. Ed. James Friedman. New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press, 2002. Print.

Genette, Gérard. Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree. 1982. Trans. Channa Newman and Claude Doubinsky. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. Print.

“Grizzly Bear Man.” By Travis and Jonathan. Travis and Jonathan, 16 November 2009. Web. 28 January 2010. ;.

“The Grizzly Man Diaries.” Animal Planet. Discovery Communications, 2008. Web. 15 April 2009. ;.

Häntzschel, Jörg. “Die Hornisse.” Süddeutsche Zeitung 4 February 2010: 3. Print.

Herzog, Werner, perf. Encounters at the End of the World. Dir. Werner Herzog. 2007. Image Entertainment, 2008. DVD.

—, perf. The Grand. Dir. Zak Penn. 2007. Anchor Bay, 2008. DVD.

—, perf. Incident at Loch Ness. Dir. Zak Penn. 2004. Twentieth Century Fox, 2005. DVD.

—, perf. “It’s a Black President, Huey Freeman.” The Boondocks. By Aaron McGruder. Adult Swim, 2 May 2010. Web. 21 September 2010. ;.

—. “The Minnesota Declaration: Truth and Fact in Documentary Cinema.” Cronin 301-302.

—, perf. My Best Fiend [Mein liebster Feind]. Dir. Werner Herzog. 1999. Anchor Bay, 2000. DVD.

—. “Werner Herzog.” Interview by Mark Kermode. Guardian.co.uk, 26 January 2009. Web. 27

February 2010. ;.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1985. Print.

Iverson, Ryan. “Werner Herzog Reads Curious George.” YouTube. YouTube, 15 January 2010. Web. 4 March 2010. ;.

—. “Werner Herzog Reads Madeline.” YouTube. YouTube, 28 February 2010. Web. 4 March 2010. ;.

—. “Werner Herzog Reads Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel.” YouTube. YouTube, 31 January 2010. Web. 4 March 2010. ;.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. Rev. ed. New York and London: New York University Press, 2008. Print.

Juhasz, Alexandra and Jesse Lerner, eds. F Is for Phony: Fake Documentary and Truth’s Undoing. Minneapolis and London: University of Minneapolis Press, 2006. Print.

Kilborn, Richard. Staging the Real: Factual TV Programming in the Age of Big Brother. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2003. Print.

Klinger, Barbara. Beyond the Multiplex: Cinema, New Technologies, and the Home. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006. Print.

Kniebe, Tobias. “Der Vernünftige: Werner Herzog muss jetzt doch mal etwas richtigstellen.” Süddeutsche Zeitung 25 February 2010: 12. Print.

Lipkin, Steven N., Derek Paget, and Jane Roscoe. “Docudrama and Mock-Documentary: Defining Terms, Proposing Canons.” Docufictions: Essays on the Intersection of Documentary and Fictional Filmmaking. Ed. Gary D. Rhodes and John Parris Springer. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland, 2006. 11-26. Print.

Maier, William, perf. “Cooking with Werner.” Sandwich Films, 2009. Web. 24 February 2010. ;.

—, perf. “Werner Herzog Live Appearance, 11.14.09.” Vimeo. Vimeo, 17 November 2009. Web. 24 February 2010. ;.

Mathijs, Ernest and Xavier Mendik, eds. The Cult Film Reader. London: Open University Press, 2008. Print.

Reitze, Matthias. Zur filmischen Zusammenarbeit von Klaus Kinski und Werner Herzog. MA thesis. U Cologne, 2000. Alfeld/Leine: Coppi-Verlag, 2001. Aufsätze zu Film und Fernsehen 77. Print.

Roscoe, Jane and Craig Hight. Faking It: Mock-Documentary and the Subversion of Factuality. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2001. Print.

Rose, Margaret A. Parody: Ancient, Modern, and Post-Modern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. Print.

—. Parody as Meta-Fiction: An Analysis of Parody as a Critical Mirror to the Writing and Reception of Fiction. London: Croom Helm, 1979. Print.

Skarsgård, Stellan, perf. The Entourage. Season 5. HBO Home Video, 2008. DVD.

Snickars, Pelle and Patrick Vonderau, eds. The YouTube Reader. Stockholm: National Library of Sweden, 2009. Print.

“Spaß mit Werner und Klaus!” YouTube. YouTube, 25 October 2006. Web. 1 April 2010. ;.

Walsh, Gene, ed. “Images at the Horizon”: A Workshop with Werner Herzog. Chicago: Facets Multimedia, 1979. Print.

“Werner Herzblog.” April-December 2007. Web. 29 December 2009. ;.

“Werner Herzblog.” The Stranger. Index Newspapers, n.d. Web. 29 December 2009. ;.

“Werner Herzog’s cave art documentary takes 3D into the depths.” Guardian.co.uk. Guardian News and Media, 13 April 2010. Web. 14 April 2010. ;.