Record of a Human Jungle

TRANSIT vol. 12, no. 1

Charles Desmet

In 2002, the French Minister of Internal Affairs decided to dismantle a refugee camp in Sangatte, which is near the channel tunnel of Calais, because the camp had been declared unstable due to overpopulation and tensions with the local inhabitants (Mulholland). Nonetheless, after the closure, a spontaneous camp later on named ‘The Jungle’ was reported near the harbor with an estimated population of a hundred people. In 2009 the population had increased to 700 (The Connexion) and by the year of 2014 it exceeded a thousand (The Guardian) with many coming through the crossing of the Mediterranean Sea. Eventually, the makeshift camp was evacuated in 2016 (Nederlandse Omroen Stichting).

This event caught my attention in 2015 while visiting my hometown close to the border of France. It’s unrealistic to believe that one is capable of understanding what it is like to live in these kinds of conditions without having the empirical experience of setting foot on the soil itself. During my journey I kept a journal and camera as a tool to document this landscape in the attempt to gain a broader perspective and better understanding on a situation occurring all over the world.

Arrival:

The train should be here any minute now. I’m heading for “The Jungle”, a refugee camp situated in the dunes near the harbor of Calais. The city is home to the Channel Tunnel, a 31.35 miles-long pipeline that runs underneath the sea and connects France to the United Kingdom—the country so many refugees are desperately trying to reach. I’m carrying 24 rolls of film, a bottle of water, my jacket, a toothbrush, toothpaste, 10 euros in cash and, of course, my camera.

I have no idea how to get to The Jungle from the station, no place to sleep, nor any sort of accommodation planned. Upon arrival in Calais, I carefully follow some people who appear to be refugees in the hope that they will lead me in the right direction of the camp. A soldier guarding some wire fences points out where to go and after an hour walk, I stand in front of this so-called ‘Jungle,’ which seems to be hidden away from public view. The camp has had many different locations over the years; time and again, police authorities shut the sites down. Now, in 2015, it is expanding more vastly than ever on this undeveloped piece of land. At first glance, the sight looks like what could be a regular campsite, although, on closer inspection, this idea vanishes in thin air like a fatamorgana. In fact, what I’m witnessing now is poor accommodation, improvised shelters and shops, hardly any toilets or other kinds of facilities and no sort of waste management.

Encounter:

Upon entering the settlement, I immediately get invited by a group of youngsters to join them for lunch. I kindly decline with the thought that food must be a scarcity here and that I would be taking advantage of the situation coming from a different background. Nonetheless, a second group will not take no for an answer, so I sit down and join them. In the middle of a circle of people, a cooking pot filled with white beans in tomato sauce is being heated on some burning logs.

I get a piece of bread. They show me how to eat with my hands and have a good time laughing at my clumsiness. Now and then, my teeth grind from the sand that’s blown into the cooking pot. We start a conversation, mainly about me and my reason for being here.

Later that day, I get a tour around the camp from one of the local do-gooders who’s stationed here. He explains to me that the camp is divided by what you could call invisible sections. These sections are organized according to country of origin and/or religion. Nobody coordinated them into this particular arrangement, it seems to have manifested itself in a rather organic way, a search for comfort and identity, giving shape to the landscape. The dominating countries inside The Jungle are Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Ethiopia and Eritrea. This turns the camp into a peculiar cross-section of neighboring cultures, including the ones officially at war with one another. This can create tension between some of the cultures from time to time but overall the atmosphere remains calm in light of the common interest in a sustainable future.

New beginnings:

Last night I slept in a two-person tent with five Eritreans around the age of 18. Not very comfortable with that many in a small tent, but this had proven to be very helpful in keeping us warm during the night. One of the youngsters calls himself John. “That’s my English name”, he says. Often refugees give themselves English names and change their date of birth to appear 18 years old or older to meet the legal requirements for getting a job. Regrettably, though, plenty of the refugees here are under the age of 18.

Today is New Year’s Day in Ethiopia and everyone seems to be excited. Also, the Eritreans celebrate this occasion today while they used to be in a federation together with Ethiopia up until 1991, when the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front won their independence after 30 years of war. The group invites me to go and pray with them in the St. Michael’s church for the occasion. The church is located nearby and is built out of wooden planks and big plastic banners, a proper piece of craftsmanship. Still outside, the people pray for their families and relatives. John explains to me the tradition of praying for personal beliefs and/or wishes outside and directly to and for God once inside the church. Before entering we take off our shoes and kiss the holy book. I choose to stay in the back while all the men go and sit on the left and all the women and children to the right from where I’m standing. Singing and clapping hands make the ceremony feel more like a festivity compared to my childhood experience of going to church.

Many of those in attendance are recording the event with their phones so that they can share this moment with their loved ones back at home. I imagine being able to do so makes life more bearable when separated from family and friends. Afterwards, everyone gets a plate of chicken with injera, the traditional bread. They also receive a coupon for fresh clothes that they can pick up at the church in town.

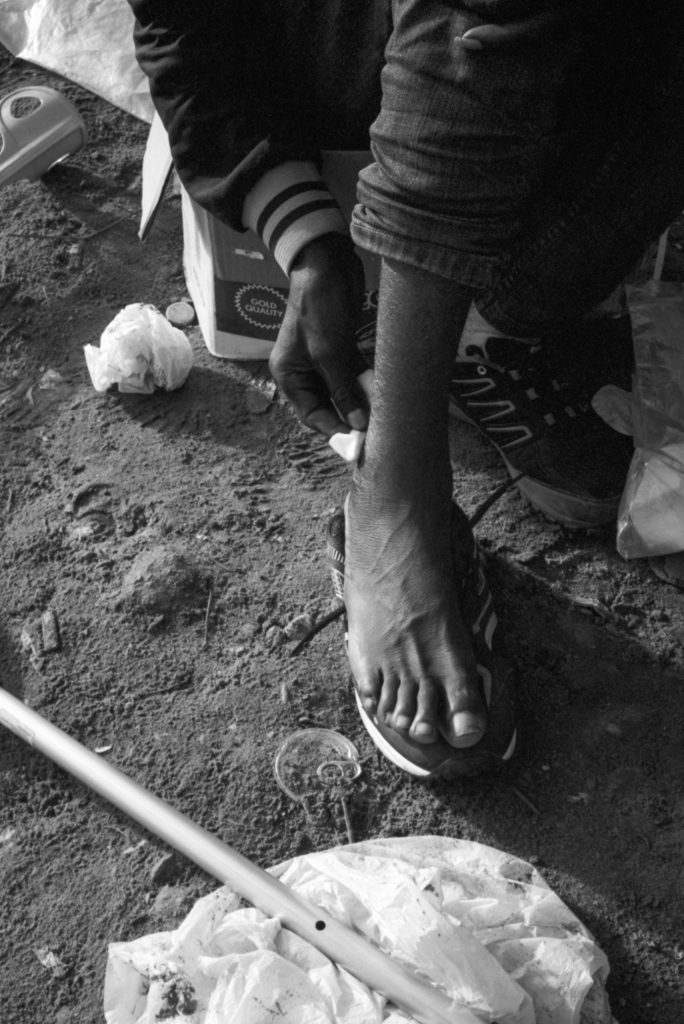

Clothing is rather important since it can get very cold near the sea, especially compared to the climate most refugees are used to. Shoes in particular are not easy to find. Most of them are either too small or too big. People do solve these problems creatively by cutting of the toe cap or wearing them like slippers by flattening the heel of the shoe.

Rain:

It’s raining today and we need to stop the water from flowing into the tents. Nadir, a youngster from one of the neighboring tents, fetches himself a shovel and starts making small piles of dirt, big enough to stop the water from coming through any further. This kind of weather turns the soil into a mud-pool, and we have to be careful not to lose a shoe when walking through the dirt. Another more important consequence is that the chance of successfully climbing over the wire fences, blocking access to the Eurotunnel, become slimmer; the task itself becomes a lot harder and more dangerous than it already is. Many who try twist or break a limb. Some even die in the attempt to try and hop onto the departing trains.

All of a sudden, a mass of people starts running towards a big truck carrying an English license plate. Apparently, they’re handing out food packets containing bread and rice. “First come, first served” is the rule in The Jungle. People here are very dependent on this kind of organized help from outsiders. Through this way they are able to collect food and other supplies needed for survival. It’s a good sign that not everyone has given up on the refugee crisis.

A waiting game:

The weather hasn’t improved a bit, resulting in the destabilization of the tent. Not wasting any time, Michale and Daniel start fixing the tent in the sand again, providing a more comfortable shelter. There is a continuous stream of people arriving in The Jungle and because of this the number of tents is growing day by day at such a rate that they’re starting to exceed what the police consider to be the borders of the camp. There is hardly any free space inside the camp left leaving newcomers with almost no choice but to put up a tent on the edge of camp. For the Eritrean people this means they have to get close to the wire fences on the other side of the bridge. These fences came about after a game of finger pointing, and border barriers preventing refugees from reaching the harbor, highway, or Eurotunnel were constructed because France threatened to block the port of Calais if England didn’t take action against the immigration problem.

Supplies:

This morning I decide to go home with the intention to return with materials for some of the people I met here. Most important, they say, is wood. It’s useful for building small structures and cooking fires. Secondly, they would like something to distract their minds from their current situation–make some music, play some sports, something…

A few days ago, a man came and played the guitar. When he started playing, a group formed around the musician, listening, and wanting to try out the guitar for themselves. It was as if the air had changed for a moment and tension had dropped. I think that recreation can easily be underestimated in a situation like this. It’s not the first thing authorities have in mind when dealing with a crisis like this, yet, in the long term, I believe it to be crucial for one’s psychological health. I imagine that an emphasis on it would be hugely beneficial, even at the later phases of the immigration process, when refugees are integrating in Western societies.

Return:

Today I come by car and in the back, I’ve got wood and other goods I assume to be useful. A lot of new tents have been put up again. The stream of people finding their way here continues to grow. I deliver the wood and a smile appears on their faces. The younger ones immediately get a fire started as the older ones discuss what to cook. Meanwhile Mimi, the first woman I met here, is doing the dishes with a bottle of shampoo she got together with other bathing supplies from an organization going around the camp. I ask her whether she would prefer to use a more proper product for doing the dishes to which she replies, “Do what you think you have to do but just don’t waste your money on me, I’m not planning on settling down here.” She starts to laugh.

Two policemen approach the younger ones and order them to extinguish the cooking fire underneath the bridge. “It’s damaging the structure,” they say, which, to me, seems reasonably doubtful. It looks like they’ll have to try to get a fire going in the rain.

Hoesyn, someone I go and see on a regular basis, still doesn’t have any shoes and I promise to bring him a pair tomorrow. I’ll be going back and forth more often now—I might as well provide more sustainability for some by delivering materials needed to make life here a bit more comfortable. Talk is going around that Effrem, one of the Eritreans I share tents with, almost managed to make it to England. He was hiding quietly between some boxes of wine when the police found him. After the authorities took him in the police car and dropped him off behind the wired fence, he simply tried again. Hopping the train is a game of luck, one that refugees here try to play as often as possible in the hopes of raising their chances of success.

Voices from The Jungle:

There’s not much going on today and the camp looks as if it is abandoned. Someone tells me there is a huge demonstration going on in town and that that is where I should go. Suddenly, loud voices appear to be coming from the entrance, so I decide to go back and have a look.

I see a woman shouting through a megaphone—it appears that a women’s protest is taking place inside the camp. So far, I’ve hardly seen any women around here. I was informed that when families arrive, mother and child are immediately separated from the men in the camp and transferred to a shelter in a nearby building provided by the government.

The women protesting are holding signs reading “The jungle is not for us, the jungle is for animals” or “Where are our rights?” Some of the signs list their professions: “I am a lawyer, I am a doctor,” and so on. All of the signs name highly respected positions in order to show that being a migrant doesn’t mean they haven’t had an education. I recall a conversation I had with a surgeon telling me that most of the people here now are the ones who can afford to pay the large sum of money for the crossing, even if this means selling most of one’s belongings, and that only later will the people who can’t afford it (and therefore undertake a large part of the journey on foot) begin to arrive as well.

A few journalists start to take an interest in the scenery and quickly begin their routines. Almost like a hit and run, they take some photographs, ask a few questions and leave. It’s hard for journalists to translate subtle issues related to migration in an objective manner as they have to tend to the status quo which, sadly enough, is achieved by creating sensation rather than information.

Raid:

It’s been a couple of days now since I’ve been to The Jungle. I hope to see some familiar faces, but then again, I don’t. Going by train I notice that the security level on public transportation has increased. The police are patrolling the train in case refugees want to get in or out of Calais.

Walking towards the camp, John and the others spot me from across the road. “We’re heading for the tunnel,” John says, and I decide to follow them. He tells me a lot has changed during my absence. I tell him my attention was required at home for family matters.

John starts telling me that a couple of days ago a police raid took place in the part of camp which exceeds the considered border. This occurred in the early morning, during the hours most of them are still asleep after trying to hop the train all night. All their possessions, including their tents, were destroyed in the process, leaving behind a big pile of garbage bags in front of the camp. John and many others had lost everything: their identification papers, cash, mobile phones, family pictures… the few things still of value to them were now on their way to the garbage fields. He tells me how people tried to argue with the police to at least give them some time to gather their belongings. Unfortunately, though, this suggestion was answered with pepper spray instead of dialogue. John tells me they’ve been sleeping underneath a bridge close to the Eurotunnel so as to avoid having to make the trek from the main camp. “It’s the only thing I try to do now,” he says, “to get on that train.”

Crossing:

No sign of anyone familiar today. I ask some folks whether they know John and if they’ve seen him around. Someone says the words, “John England”. If that’s true I’m happy for him. I keep looking around though and find a familiar face—Nadir. He guides me to his current location. “Everyone is spread throughout The Jungle now,” he says. I give him the phone I meant to give John and together we go charge its battery. He talks about how a child from Eritrea died last night attempting to jump on the train. Casualties like that are unfortunate but nevertheless frequent here. I just hope it wasn’t John.

Separate paths:

I haven’t heard word from John in the last two days leading me to believe he made it to England. Though, I can’t be sure until he replies to one of my messages. Amadin, a friend of John, has built a restaurant in the Jungle and invites me to drink a tea with him. He is proud of his accomplishment. There are many shops and services to be found here, from cafés and restaurants to barber shops, a sign that people try the best they can to make a living out of this situation.

Amadin has been here for almost three years now and has lost all hopes of getting to England. “I might as well make the best out of it here,” he says.

My friend Mimi and some of the others built a small wooden cabin on top of one of the many sand dunes. “Beats sleeping in those horrible tents”, she says. The shelter they’ve built is more suitable for the surrounding conditions and provides shelter for at least four people. It even contains a small gas stove on which they can cook. Here, the wretched events have been transformed for the better. This is not the case for everyone though. On my first day here, I met a person who broke his foot falling down from a wired fence. Because of the recent raid he had to find a new tent leaving him all by himself. With limitations in mobility and health, his life has come to a rather depressive state. “How can we ever trust the police again after what they have done to us here?”, he says. The raid has left many refugees with rage and push them to certain extremes, threatening anyone, even the innocent, who prevent them from reaching their goal. These people are here because of conflicts beyond their power that lead some into acts of despair.

Free of burden:

The road into the camp is blocked by police officers. I drive around a while trying to get in from a different direction. Making it inside the camp I head for the man with the broken foot. Today his plaster will finally be removed, and he asks me if I could keep an eye out for his stuff while he’s at the hospital. I bring him to the medical post inside the camp and from there they’ll bring him to a doctor. Coming back, freed from the plaster around his foot, he says the doctors told him to wait one month before walking on it again. They gave him some syringes which he has to inject himself. I ask him what the syringes are for. “I don’t know” he says pulling out the needle and holding a cotton ball against the wound. “Ten days I’ll wait and then I’ll get the hell out of here,” he adds. Lots of heavily armored policemen are patrolling inside the camp these days, though this doesn’t add up to a feeling of security, but more to that of being imprisoned.

Departure:

I slept in a different tent last night which has a more central position inside the camp. The more towards the center, the worse conditions (such as excessive quantities of garbage) can get. Consequently, this creates an enormous playground for rats. They run around at night, slipping past you as they try to get to the inner section of the tent. Mainly because this is where people store their food.

Today my story inside The Jungle will end.

The encounters I’ve made here in Calais over the past days made it clearer to me what sorts of transformations had taken place that gave this landscape the name of “The Jungle.” Sand dunes became the soil of improvised homes. Wired fences, with their monumental strength reminding us of the tragedy passing through this town day by day, shoot out of the ground, while police patrol those they might see as animals in a cage. What once used to be your picture-perfect seascape has now been transformed into a scar of human suffering.

Nevertheless, this landscape contains hope. A community has sprung out of the bottom of the sand proving to be resilient and determined in building shelters, shops, cafés and other community facilities. We have heard their roar from deep within The Jungle awakening some and leading them into action. It’s not at all clear what evolution awaits this landscape but surely, its transformation isn’t over yet.

Works Cited

“Calais mayor threatens to block port if UK fails to help deal with migrants.” The Guardian, 2 September 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/sep/03/calais-mayor-threatens-block-port-uk-fails-help-migrants. Accessed 4 April 2019.

Dawn raid on Calais “Jungle.”” The Connexion, 22 September, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20150923210243/http://www.connexionfrance.com/news_articles.php?id=1076#. Accessed 4 April 2019.

Mulholland, Rory. “Calais crisis: Bicycle repair shops, mosques and an Orthodox church – the town where migrants wait to cross to Britain.” The Telegraph, 5 July, 2015, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/11718598/Calais-crisis-Bicycle-repair-shops-mosques-and-an-Orthodox-church-the-town-where-migrants-wait-to-cross-to-Britain.html. Accessed 4 April 2019.

“Ontruiming vluchtelingenkamp Calais verloopt rustig.” Nederlandse Omroep Stichting, 24 October 2017, https://nos.nl/artikel/2139334-ontruiming-vluchtelingenkamp-calais-verloopt-rustig.html. Accessed 4 April 2019.