Dodos on the Run: Requiem for a Lost Bestiary

by Mikael Vogel

TRANSIT vol. 12, no. 1

Translated by Jon Cho-Polizzi

Translator’s Introduction

Is it coincidence or fate that a writer with the last name ‘bird’ would take such interest in his namesake? Perhaps it’s both, but Dodos auf der Flucht. Requiem für ein verlorenes Bestiarium [Dodos on the Run: Requiem for a Lost Bestiary] is far from an extended swansong for the extinct animals Mikael Vogel’s work evokes. It is a collection of poems and prose as much dedicated to the shrinking biodiversity of our globe as it is a reflection on human causality—an at times caustic indictment of a laissez-faire interpretation of natural history as ‘survival of the fittest.’

Vogel’s writing process often begins with archival research, and the German-language originals of his poetry at times invoke acts of translation themselves: Many are couched in the registers of historic violence. In recontextualizing the surviving memoires of exploration—the observations and assessments of Darwin, Leguat, van Linschoten, Audubon, and Steller (to name a few)—focus shifts to the specific, personal narratives which have molded contemporary understandings of natural history. From early-modern travel narratives to the feigned objectivity of modern text book analyses, Vogel’s collection negotiates a plurality of historic and contemporary voices: tracing the human reception of endangerment and extinction across the centuries and searching for those disappearing animals left behind and in-between.

The questionable legacy of early modern science maintains a visible presence throughout his work. The struggle between European and indigenous naming systems, the mercantile commodification of the natural world, and often-visceral accounts of first encounters and exterminations at times threaten to inform new objectivizations of the deceased, but a form of agency, too, is encountered in the caesurae between Vogel’s mediations. The animals at the heart of these poetic interventions reveal themselves in the conflicting imaginaries proliferating in their collective absence, the precise attention to their anatomic detail, or—from digital recordings of extinct bird song to display case drawers of taxidermied animals—the author’s recourse to the surviving material record. The resilience of nature, too, alongside the human role in establishing and maintaining its discourse remain underlying counternarratives to the subject matter: a world in which volcanic winter can inspire “Biedermeirliche Sonnenuntergänge von niedagewesener Farbpracht” [Biedermeier sunsets, the glory of unprecedented hues].

Ostensibly dedicated to those new initiates to the growing list of human-induced extinction, Dodos auf der Flucht is also a sardonic history for that most pernicious of animals: human beings. Historical narratives and extant material evidence elucidate the interrelation between human migration, climate change, and mass extinction: the debilitation of Earth’s once-astounding biodiversity recast as colonial enterprise. Humans are, after all, in Vogel’s desiccating humor: “Auch nur ein Säugetier: Trockennasenaffe aus der Ordnung der Primaten / Einziger Affe von dem bekannt ist dass er leugnet Affe zu sein / Kriege anzettelnd um noch einmal auf allen vieren zu kriechen” [Still just a mammal: haplorrhine of the order Primates / The only ape known to deny its apehood / Instigating wars to crawl again upon all-fours].

Berlin-based Mikael Vogel’s recent publications include the 2018 Dodos auf der Flucht (Verlagshaus Berlin), Massenhaft Tiere (Verlagshaus J. Frank, 2014), and Kassandra im Fenster (Offizin S., 2008), a cooperative work with Friederike Mayröcker and Bettina Galvagni. A 2015 recipient of the Yakiuta Reisestipendium, Vogel’s projects involve acute engagement with the material record of his subject matter—a practice which has taken Dodos years in the making. He was awarded a Jahresstipendien für Schriftsteller for 2019 from the state of Baden-Württemberg and has been selected as one of the year’s German-language authors for Versopolis Poetry, a digital literary platform and analog network facilitating contact, translation, and exchange between 15 European literary festivals from London to Lviv. A selection of his poetry with English translations was published digitally by Versopolis in 2019.

The following translations include the poem “Der Carolinasittich” and excerpts from the short essay, “Von Seltenheit,” one of several prose afterwords to Dodos auf der Flucht. With its emphasis on the fragility of Earth’s island ecosystems, the essay provides contextualization for his larger project: reflections on the fraught relationship between migration and the natural and human landscapes which continue to facilitate the modern wave of mass extinction, our Anthropocene.

Translations

On Scarcity (Confessions of a Japanese Strychnine Eater)[1]

25% of species comprise between 90-95% of all individuals on Earth.

On the other hand, three-quarters of the species on our planet are rare. The diversity of life on Earth is, in this sense, a question of scarcity.

Although islands represent only 3% of the Earth’s landmass, they harbor more than half of its endangered species.

This is not only because the human impact on plants and animals is more immediate there—due to islands’ relatively small surface areas, they have less room to avoid us. It is also because islands have always been a place of uniqueness, of eccentricity. They are natural experimental labs for the extravagant, the fantastical. Islands also have especially much at stake to lose: precious beings that often exist there and nowhere else.

Japan is an archipelago of 6852 islands, the largest of which is the main island of Honshū. Diversity is actually unusual on islands; Hawai’i’s biodiversity (before the arrival of human beings) was an exception to this rule. Islands display staff vacancies: There are not always enough pioneers to occupy all niches in the daily winning of bread. Islands may be free of cats, foxes, or martens, and these niches are then filled by other animals like birds. Islands can be completely free of spiders. Or free of mammals, like New Zealand, whose only large predator before the arrival of Homo sapiens was Haast’s eagle. Despite its three-meter wingspan, it was slated for extinction when human beings eliminated its primary sustenance out from under its talons—the giant, flightless Moa bird. Islands are incomplete collections of unique specimens. Consequently, one could also say that islands are collections in the works. Collections in which evolution retains room for new, surprising ideas.

Japan has the dubious glory of having been inhabited by two different species of wolf, and having deliberately exterminated both of them. The Honshū wolf, Nihon Ōkami, lived on the islands of Honshū, Kyūshū, and Shikoku. With the sunken sea-levels of a past ice age, its ancestors migrated long ago to Japan from the Korean Peninsula. Generation after generation, a transformation occurred which can happen to larger animals on islands with scarce resources and confined habitats: The Honshū wolf shrank until—with a shoulder-height of merely 50 centimeters—it was presumably the smallest species of wolf in the world. One day, it found itself in the way of human beings nonetheless. Previously, humans had tolerated them from a distance; contrary to their reputations, the wolves observed their human neighbors with caution. In fact, the Honshū wolf was already so rare, so infrequently sighted, that it had long been regarded as a ghost. Nothing but a voice, a nocturnal howl: an abstraction inviting myth. Incorporeal. The ancient Japanese called it The Pure and Great-Mouthed God. Holy to peasant farmers, protector of seeds from wild boars, rodents, deer. In gratitude, they left offerings of beans and rice for the wolves’ newborns before their lairs. Shrines stood along the roadways for their worship; wolf talismans protected against thievery, arson, sickness. And then the deal-breaker: the arrival of rabies in Japan. The first case of rabies was reported in 1732 in Dejima by Nagasaki—during the Edo period, the only port open for trade and exchange to the outside world. Just four years later, it had reached Edo, modern-day Tokyo. By 1761, it had spread to the northernmost extensions of Honshū and large swathes of greater Japan. The sick wolves fly at you just like birds Nishimura Hakū maintained in his account of the 1730s, Enka kidan, first published in 1773. The primary carriers were dogs—also the primary victims of the illness. Nevertheless, ceremonies drew together clamoring bands of armed samurais with standard bearers and hundreds of volunteers to rid the forest of what had become demonic, human-eating wolves. The image of the wolf had been irreparably transformed. All signs pointed to its extermination. In pursuit of a deer, the last Honshū wolf fell before the rifles of three local hunters near Washikaguchi on January 21, 1905. The hunters threw its corpse onto the trash. Two days later, they fished it back out, having heard that a foreigner staying at the Hōgetsurō Guesthouse was passing through and purchasing the bodies of dead animals. The foreigner was none other than the American, Malcolm Andersen, traveling under contract by the London Zoological Society and the British Museum of Natural History to acquire the pelts and hides of exotic animals. After haggling with the help of a translator (who later noted all this down), the price for the last Honshū wolf killed came to ¥8, a value of approximately €150 today. The last Honshū wolf stands taxidermied in the British Museum in London. Other than this specimen, only four preserved bodies remain worldwide of the Honshū wolf today: three in Japan, one in Holland.

Having migrated far more recently from Siberia, the Hokkaidō wolf, Ezo Ōkami, stood comparable to North American and Eurasian wolves at a shoulder-height of 80 centimeters. It, too, was once revered—less an animal in the zoological sense of the word than one in transcendence into myth—as messenger of the gods, acting only as a positive, spiritual entity. For how should it be an actual, corporeal being when encounters consisted merely of the sounds of distant howling in the woods at night? The discrepancy with the Western image of the wolf could hardly be more blatant: In Germany, during the Middle Ages, one could pay taxes in wolfskins—the destruction of a wolf’s life was worth at least as much as cash. In early Japanese poetry, wolves were still portrayed as godlike beings: filling poets’ lines with wabi, that specifically Japanese and largely untranslatable feeling of misery, solitude, loss, and transience. In embodying the forests—those sacred and potentially savage regions beyond palace and settlement walls—wolves reflected back humanity and its insecurities, the uncertainties of our capacity for imagination. With the end of Japan’s isolation—its transition to modernity and its orientation toward the West—came Western solutions for Japan’s wolves, too, executed with Japanese efficiency. At the conclusion of their systematic total annihilation, the only two remaining bodies of the Hokkaidō wolf stand mounted in a small, inconspicuous museum building in the sumptuous greenery of the University of Sapporo’s Botanical Garden. The pastel, lime-green wooden house containing them bears no inscription, no further indication that it displays something ancient and wild, something of the holy uncanny Hokkaidō within its walls. It appears like a set piece from the Wild West—one further reflection of Western influence there. The staging of the specimens inside offers an indication of how even extinction is threatened by history’s perpetual recording from the perspective of the victor. How, instead, might a historiography have appeared from the perspective of the Hokkaidō wolf? How might this eater of strychnine—in reflection on its life, the cause and the effect—have depicted this escalation of events? Would it, too, have regarded these as inevitable?

It is puzzling that even in the animistic Japanese culture—in which toys, dolls, and even everyday objects like pots and pans are considered to have souls—a once venerated being could become the object of unconditional annihilation. Even today, dolls in Japan are not thrown away by all. Some are still ceremonially cremated in a temple during the ritual of ningyo kuyo, the doll funeral, to appease these discarded companions and friends. Every September 25th, at the Kiyōmizu Kannon-dō Temple in Ueno Park in Tokyo, visitors can observe monks burning the year’s abandoned stuffed animals and dolls—brought as sacrificial offerings by women desiring children of their own. According to an old belief, every artifact develops a soul after a symbolic age of 99 years. As soon as it is no longer in use, it begins to haunt. This artifact could be an old hat, a used suit, a chest of drawers, pliers, grandpa’s childhood bike, or a VHS tape—that lonely straggler from the ranks of an extinct technology. This belief has its roots in the uniquely Japanese nature religion, Shintō, according to which not only human beings have souls, but all beings possess this potential: animate and inanimate alike. Still, remarkably, the habitats of endangered endemic species like the Amami rabbit or the Okinawa rail are repeatedly destroyed for the construction of golf courses and resorts. Despite the fact that these animals are protected by law. Because the destruction of habitats—so goes the argument—doesn’t harm the animals directly, this remains legal. In contrast to animism, Western understandings of philosophy and religion continue to facilitate our ability to ignore their suffering with the belief that animals have no souls. One way or another, in the end, humans succeed in maintaining our license to kill. To legitimize exploitation and abuse.

In some cases, the historiography of an extinct animal is limited—at least from a human perspective—to one single moment. Only a single snapshot. And no name is as connected, for me, with the isolated descriptions of lost species than that of Heinrich von Kittlitz. In the Pacific theater of the early 19th century, this German ornithologist, naturalist, artist, and traveler continually arrived at the ‘right’ place and the ‘right’ time to discover and document bird species as yet unknown to Western science. Travelling from island to island as a ship passenger at his own expense, he managed to document the first and only accounts of these rare animals, many of which had already gone extinct by the time Kittlitz returned from his world tour. Without lucky Henry, zoology would never have known many of these now-extinct species of birds. The Kosrae crake, also known as Kittlitz’s rail, was discovered by von Kittlitz during his stay from December 1827 to January 1828 on the Island of Kosrae in the Eastern Carolinas—one of the more than 2000 islands and atolls of Micronesia. At an unknown date sometime in the following fifty years, the bird was driven to extinction, presumably by rats brought to the island aboard whaling vessels. The Kosrae crake was never seen alive by another Western scientist. The Bonin grosbeak was found only on the Island of Chichijima in the remote Japanese archipelago Ogasawara-guntō, also known as the Bonin Islands, lying 1000 kilometers southeast of Honshū. Von Kittlitz was also the only one to ever describe this bird alive, and probably the last to see, capture, and kill living exemplars. I had to search through the entirety of Kittlitz’ life works to find this single description in his Kupfertafeln zur Naturgeschichte der Vögel [Copper Plates on the Natural History of Birds], published in 1832: The Bonin grosbeak lived solitarily or in pairs in coastal woodlands, untimid, though often remaining hidden from view. It preferred walking on the forest floor to perching in the trees. It was never plentiful…

Seen in literary form, as in reality, it may be difficult to distinguish between natural and human-related scarcity—because scarcity was seldom observed before the human impact on a place had already left its mark. Schrödinger’s cat would understand this problem. In the future, will scarcity continue to have its place on our planet? If so, where? In niches still smaller and more isolated than islands? For a time, there will be a temporary boom in scarcity as more and more species are driven to the margins of existence. Thereafter, scarcity, too, will become a rarity.

Along with bacteria and viruses, humans represent the inverse of scarcity on this planet. As a land mammal of more than 50 kilograms, we are already 135 times more plentiful than any other land mammal of our weight class in the history of life on Earth. Population trends are rising. Our biomass, the sum total of the weight of all humans, is estimated to be ten-times higher than the combined weight of all wild mammals on Earth. Our domestic animals, in particular cattle and swine, comprise an even greater biomass: 25 times more than that of all wild mammals. Noah has filled his ark with factory farms.

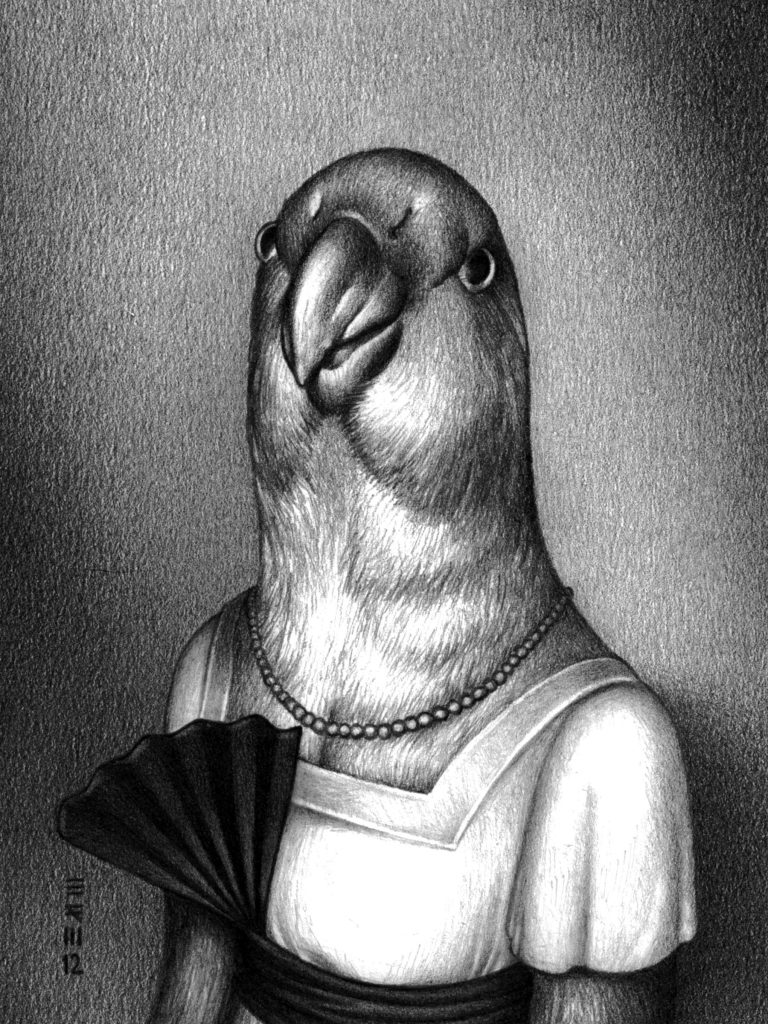

The Carolina Parakeet

Husky

Voice, chattering

Incessantly, with yellow-orange crest

Scarlet brow as if from crushing strawberries

Cascading luminescent green from its throat..

Sole parrot of North America’s East Coast

At home in deepest winter, blizzards. Was toxic: Cats

Died from consumption. By plantation masters decried as

Vermin because it ate their seeds, plucked their fruit – abusing their affection for one another

For carnage, shooting down to screeching death those flying to their fellows’ aid

En masse until the flock was annulled.

Riparian woods with ancient, hollow trees ripped out from

Beneath its claws

Its feathers and taxidermied body

Coveted as pageantry for women’s hats. Undesirable as pet:

Gnawed furniture, its shrieks unbearable.. dunked incessantly in

Water as domestication rite, forever wild, refusing to acquire human speech.

Left-footed. The last Carolina parakeet [his name was Incas]

Died on February 21, 1918 at the Cincinnati Zoo

In the same cage in which

Four years before, the last passenger pigeon Martha

Died

[1] A longer version of this essay was first published together with a collection of other short essays at the conclusion of Dodos auf der Flucht as “Sonagramme aus der Aussterbewelle” [Sonograms from the Extinction Wave].