Towards a European Postmigrant Aesthetics: Christian Petzold’s Transit (2018), Phoenix (2014), and Jerichow (2008)

TRANSIT Vol. 13, No. 1

Jennifer Ruth Hosek

Abstract

A contested polity and an imagined community, Europe is confronting a myriad of political, economic, and climatic shifts. Ethnographer Regina Römhild has recently argued that understanding Europe as homogeneous and clearly demarcated inaccurately conjures a truncated White entity quite distinct from that which its early founders imagined. Römhild juxtaposes a Europe traditionally, historically, and fundamentally constituted by migrancy. She shows the fundamental importance of neo/colonial entanglements, sketches Europe as part of a black Mediterranean (cp: Paul Gilroy), and explains how resistant, anti-colonial imaginations variously shape this union. In these ways and more, Europe has always already been constituted through exchange, movement, and porousness. Drawing on Römhild, I analyze Berlin School filmmaker Christian Petzold’s films Transit (2018), Phoenix (2014) and Jerichow (2008) with an eye towards what I dub their postmigrant aesthetics. Drawing on sociologist Jin Haritaworn, I pay special attention to these works’ commentaries on “regenerative” minorities. Further, I argue that these films also highlight limitations of the concept of postmigrant Europe. Even if historically accurate, it cannot (yet) be understood as normative, but rather aspirational, because in our real-existing Europe, power dynamics between individuals and communities inhere and continue to thwart equitable participation. Artistic production and aesthetics have especially important work to do under such circumstances; I suggest that these recent films by Petzold invite viewers to notice and (re)consider complicities in this power differential and to imagine and work toward a postmigrant Europe.

At the June 2020 e-conference “Postmigrant Aesthetics: How to Narrate a Future Europe?” keynote speaker, Humboldt University professor of ethnography Regina Römhild argued for defining Europe as postmigrant.[1] Römhild genealogized such a Europe, reconceptualizing it against contemporary normative definitions. In the latter, Europe is imagined as a relatively homogeneous polity whose well-defined borders are in danger of being overrun by waves of immigrants. This Fortress Europe is under attack, especially by way of the Mediterranean Sea route. Against this ideological, false myth of what Römhild considers an amputated, White Europe, she juxtaposes a really existing entity traditionally, historically, and fundamentally constituted by migrancy, even if its real-world existence is not typically recognized by majority opinion. Most notably, the mainstream has yet to recognize the ways in which Europe has for centuries deployed colonial entanglements and, more recently, neocolonial entanglements to its great benefit. Drawing on Paul Gilroy’s conceptualization of the Black Atlantic, Römhild evidences Europe and the Black Mediterranean as in fact mutually constitutive. She highlights the “minor cosmopolitanism” of British author Johny Pitts’s Afropeaness.[2] She demonstrates how resistant, anti-colonial imaginations influenced and still influence Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and the former colonies. Römhild shows that although “multicultural” Europe is typically understood as new, this heterogeneous polity is actually a more historically accurate way of describing Europe from its beginnings. The postmigrant condition fundamentally constitutes Europe.

This conceptualization of Europe provides a rich basis for consideration of postmigrant aesthetics, that is, expressions of this postmigrant reality in cultural production. Nascent as the concept—if not the reality—of postmigrant Europe is, Römhild suggests that attendant postmigrant aesthetics are only just becoming legible. For at least the purposes of this paper, I define postmigrant aesthetics as an aesthetics that narrates Europe and European nations as fundamentally postmigrant. By my definition, such aesthetics tend to unsettle ideologies—such as notions of Leitkultur—that misleadingly cast migrants as threatening to a homogeneous “real Europe.”[3] They further non-dominant, more equitable understandings of an expansive, heterogeneous Europe. As such, postmigrant aesthetics work on at least a double track. First, they articulate what Römhild insists Europe is in reality—even if a majority of intellectuals and average citizens persist in championing a mythical “amputated, White Europe.” Second, through such articulations, postmigrant aesthetics express and work towards a utopic future in which postmigrant understandings of Europe are more common and robust.[4] In what follows, I analyze Christian Petzold’s Transit (2018), Phoenix (2014), and Jerichow (2008) in terms of their postmigrant aesthetics. I deploy sociologist Jin Haritaworn’s work on hate crime in Europe to argue that and show how these melodramas express (the double tracks of) postmigrant reality and utopia, notably through critical depictions of voice/silencing in diegetic Germanies variously marked by fascism, racism, and xenophobia. By contextualizing these filmic narratives in relation to real-world issues concurrent with their particular temporal moments of production, I also show how their specific postmigrant aesthetics press upon and supplement the notion of postmigrant Europe as theorized by Römhild. Namely, these films invite recognition that the gaps between this notion and hegemonic perceptions of Europe harbor particular dangers—corporeal, psychic, and social—for those who continue to be normatively understood and treated as “hateful others.”

In Queer Lovers and Hateful Others: Regenerating Violent Times and Places, Haritaworn demonstrates how practices that benefit certain minority groups can work to the detriment of other, differently intersectioned minorities. Haritaworn investigates German anti-hate crime legislation that protects particular queer communities while passively enabling crimes against people of color. In this situation, members of the former minority group function “regeneratively” (3); they index societal progress even as their relatively improved societal acceptance camouflages continuing persecutions of the latter minorities as “hateful others.”[5]

Transit, Phoenix, and Jerichow variously express this regenerative phenomenon recognized by Haritaworn. Broadly described, the films first narrate the main, identificatory minority characters as regenerative. This phenomenon starts with the ways in which ongoing “circles of conversation”[6] of and around these protagonists capture audience attention, drawing viewers into their diverse plights and subjectivities in the process. By identifying with and attending to the struggles of these fictional minorities who are vulnerable and under duress, viewers also construe themselves on the side of progress, allies against perpetrators.[7] Subsequently, the films expose the limitations of identification with regenerative minorities; such identification has precluded recognition of concomitant vulnerabilities and struggles of other minorities. Each revelation occurs through a climactic turning point in the narrative that releases what had been a protracted silencing of another, a hateful minority character.[8] In a more utopic reality, all minorities would always already be perceived and treated as intrinsic to the fabric of postmigrant Europe.

When such silencing occurs not “exegetically,” but diegetically, it is typically through circles of conversation. The sudden juxtaposition in cinematic perspective at the respective plot turning point gives voice—in word and attention—to the excluded. In so doing, this climatic pivot invites recognition of distinctions made between the oppressions and lives of the regenerative and the hateful minority characters. In his canonical monograph, Marco Abel has demonstrated that Berlin School works “forge relations with our world so that the preexisting life-world reappears as strange” (21). These Berlin School films emplot privileged circles of conversation and concomitant oppressive silencing in manners that encourage critical reflection about power, voice, and chauvinisms within and beyond the diegetic.[9]

Readers might object that deploying theory primarily understood as queer theory is out of place here, as Petzold’s characters are heteronormative and cisgender. Indeed, the current scholarly debate swings between charges of opportunistic theoretical/cultural appropriation of the margins by the mainstream and hopes for potential benefits gained by critiquing the mainstream through the margins. The very definitions of center and margin have long been debated as well. The proof of the method may well be found in the resultant pudding. In Movement and Performance in Berlin School Cinema, for instance, Olivia Landry expertly deploys José Esteban Muñoz’s theory of worldmaking to unpack meanings of car crashes in Berlin School cinema and subsequently marshals Alexander G. Weheliye’s scholarship in black studies about the body in flight to analyze actress Nina Hoss’s performance. According to Landry, Weheliye himself favors the extension of black studies theory to understand “the human condition tout court” (Movement and Performance 161). I submit that although Haritaworn takes queer minorities as their case in point, the general phenomenon that they have recognized is translatable to other instances in which differently intersectioned minorities experience different access and acceptance in society. Furthermore, it is widely accepted that theories considered mainstream do not have an explanatory monopoly on all phenomena. Likewise, theories considered to be non-mainstream can explain more than a specific phenomenon.[10] The transferability of Haritaworn’s theory must be judged by its ability to illuminate other situations. It is worth noting that other engaged scholars have similarly argued that the acceptance of certain social groups—while arguably not intrinsically wrong-headed or wrong-hearted—variously obscures and/or promotes the oppression of others.[11]

Transit, Phoenix, and Jerichow engage with the dynamics of power and privilege that Haritaworn identifies in their example of “regenerative queers.” The films articulate both the potentially liberatory aspects of attention to minorities and the necessity of attending to hateful minorities; Petzold’s regenerative characters embody intersectionalities and live concomitant oppressions. These characters function increasingly regeneratively for viewers who identify more and more with them and are drawn into their sustained circles of conversation in the diegetic. Then, an unexpected revelatory moment invites viewers to recognize that these privileged subordinate conversations have drowned out and silenced the stories of the less privileged minorities. Attention to and embrace of the sufferings of the regenerative minorities have occluded the injustices lived by the hateful minorities. Through such aesthetics of identification and revelation, these films encourage both recognition and embrace of real-existing Europe as always already postmigrant and also recognition and embrace of a yet-to-be-realized utopia in which all minorities have voice and are acknowledged to be constitutive of postmigrant Europe.

These recent films critically represent fascism and racism as sustainedly permeating European space and time, an aesthetically postmigrant portrayal. As White Europe is a myth, so non-chauvinist Europe is a fantasy; the fascism expressed in WWII was not a short-lived anomaly, but a particularly intense expression of mindsets that fundamentally shape Europe. The critical sensibility in these films of Petzold’s builds on long-standing convictions of guilt and responsibility for fascism among Europeans and particularly Germans. Since at least the 1960s, many left-leaning thinkers and activists have expressed their felt responsibility towards WWII fascism through anti-colonialist and anti-racist attitudes.[12] Drawing upon this viewer sensibility, the films link historical fascist chauvinisms to those more contemporary and racializing. Further, by articulating and valorizing such anti-fascist sensibilities, the films encourage viewers to attend particularly to the regenerative minority figures, because they emblematize minorities who are subjugated by fascistic attitudes and power structures. Finally, the films invite recognition of the potential fates of hateful minorities even during the struggle for wide-spread acceptance of the real-existing postmigrant Europe and its utopian successor; the climactic diegetic reveals suggest how chauvinisms facilitate silencings.

Phoenix and Transit are both explicitly set in relation to Nazi Germany and resonate with contemporary concerns. Their narrative arcs move from the beginning of the Nazis’ rise to power towards the present and their open endings also encourage viewers to connect the Nazi past with continued racisms in the present. Phoenix‘s climactic turning point occurs in a scene among privileged friends in a suburban Berlin villa. The viewer is encouraged to make parallels between the Nazi period and the present through a particular circle of conversation: the non-Jewish Germans vigorously occlude the just-ended War through uninterrupted prattle. This occlusion in the diegetic resonates with Normalization debates in Germany during the time that the film was being made.[13] The WWII tale Transit is set in a Marseille that is both historical and contemporary. For instance, a RAID badge—indicator of the present-day, counterterrorist, anti-migrant tactical unit Recherche, Assistance, Intervention, Dissuasion (Search, Assistance, Intervention, Deterrence)—features prominently on the uniform of the French police officer arresting persons in transit (“RAID [French Police Unit]”). Diegetically, the objective is reprieve; the risky solution is to escape from 1940s Europe, perhaps via the Mediterranean or the Pyrenees. Extra-diegetically, this objective persists in today’s Europe, especially for those having entered sans-papiers via sea or land routes. By collapsing fascist time and contemporary time into one filmic space and logic, Transit connects Nazi and contemporary Germany to contemporary France and contemporary Europe with their brutal policing of movement across borders.

Set in post-1989 Eastern Germany, Jerichow connects fascist logics to the present precisely by showing their continued influence in the categorization and perception of regenerative and hateful minorities. As in Phoenix and Transit, this connection becomes most apparent at the climax of the story. The revelation of the Turkish-German character’s sustained silencing also reveals his positionality as hateful racialized minority against the regenerative White German characters. Jerichow intervenes in a post-unification German context in which public concern and government policies shifted to support “ethnic” Germans from the former Soviet Alliance, to the detriment of support for racialized minority Germans.[14] Jaimey Fisher highlights that Petzold himself noticed challenges faced by the many Germans of Turkish descent who had migrated to the new states of Germany when he was travelling for his film Yella (120). Furthermore, Petzold is married to filmmaker Aysun Bademsoy, a relationship that influences his engagement with migrant themes, and, Joy Castro suggests, may otherwise influence his works (“Intimate Terrains”). Phoenix, Transit, and Jerichow each thematize fascism and racism in manners that encourage viewers to identify with regenerative minorities and then finally to recognize how this embrace silences and facilitates the continued oppression of hateful minorities.[15]

It may seem surprising that these films operationalize viewer sympathy. Petzold’s work is known for emphasizing subjectivizing structures and discourses such as economics, social background, and gender. Often his characters are best understood as embodied nexuses of these power discourses.[16] That said, Petzold’s earlier films, notably what is commonly called his Gespenster trilogy (Die innere Sicherheit [The State I am In] 2002, Gespenster [Ghosts] 2005, and Yella 2007), feature more Brechtian aesthetic and less psychologization than his later ones, including those that Petzold calls his “Love in the Time of Oppressive Systems” trilogy: Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014) and Transit (2018). This shift may have to do with a decreasing influence of documentarist Harun Farocki on Petzold’s work, the fact that Farocki introduced Petzold to Anna Segher’s novel Transit notwithstanding (Nelson).[17] (Farocki passed in 2014, a tremendous loss). Of Berlin School films from 2012, Landry notes “an ineluctable shift in style” towards more accessibility (158). I am reminded of New German Cinema’s Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s (in)famous turn toward more mainstream poetics. The melodramas under consideration here encourage more viewer sympathy than earlier ones. This sympathy ‘once removed’—if measured by Hollywood standards—is an attenuated sympathy that develops over the course of events and via the circles of conversations between or about the more subjectivized minority characters. By sympathizing with these regenerative minorities, viewers can complacently view themselves as holding regenerative perspectives—perspectives that express and further social progress, including rejecting fascism and its legacies.

I begin in detail with Transit for its easily legible circles of conversation. Transit‘s intricate narrative twists and turns highlight tension-laden, repetitive, and copious flows of conversation that both focus and strain the attention of viewers. Characters come into enmeshed, punctuated, and cyclical relationality with each other and with multiple embodiments of state power through their desperate machinations aimed at furthering their escape from Europe. These characters with (still) legal status in France engage in what seem endless conversations. Waiting publicly in streets, restaurants, and government offices, they speak to ferret out tips and share information about possible courses of action or inaction. They aim to solidify truths and lies about their circumstances and identities. They talk to while away the time, comfort themselves and release tensions. Their utterances are frequently alternating monologues spoken by eager mouths towards indifferent ears. Words become so much white noise, even as this palaver indexes the continued tense survival of these interlocutors.[18] At first, the main protagonist Georg wearily denounces the alienating chatter of peripheral characters who are also seeking passage, chatter that surrounds him in every public place. Subsequently, this Jewish-German camp escapee more sympathetically characterizes their words as a constitutive weft of the crowded port city Marseille that they inhabit together.

These circles of conversation incessantly engage viewers with both the regenerative peripheral minoritarian characters and with Georg himself. Many explanatory narrations are in a third-person, participant voice-over that expresses Georg’s point-of-view.[19] This privileged access to Georg’s perception of the world and his interiority encourages viewer sympathy for the regenerative minority protagonist. The initial voice-over narration articulates Georg’s intense emotional and intellectual experience while reading humanist fiction, an act all the more meaningful because it recalls Anna Seghers’ novel Transit and Seghers’s own life as an exiled Jewish-Communist author. Georg also becomes increasingly sympathetic as it becomes clear that he may be the only character in Marseille’s regenerative circles of conversation whose affections for others are not completely instrumental. He gradually falls for and seeks to help his love interest, Marie, and also develops a caring relationship to the young North African migrant Driss.

Viewers access Georg in several other ways that shore up his sympathy as a character. One visual and aural aspect is George (Franz Rogowski)’s mild, visible cleft lip that also influences his speech. While arguably “character-granting” for the normatively attractive[20] character and actor, cleft palates are characteristics that the NS answered with euthanasia. This physical attribute highlights minority status in nazifying Europe. In today’s context of disability studies and disability rights movements, the cleft lip also grants viewers who sympathize with Georg’s doubly sound regenerative positioning as they increasingly ally with the character over the course of the narrative. Phoenix and Jerichow also deploy embodiment strategically to engage viewer sympathies.

Initially estranging, the camerawork presents this refugee increasingly intimately. At first, Georg’s understated, even flat, affect and facial expressions separate him from viewers.[21] The camera supports this distancing through medium and long shots, and by depicting not more than half of Georg’s face, often with his head lowered as he looks sideways at his interlocutors. As Georg later speaks tenderly with Driss and his mother Melissa in their apartment, the camera shows Georg’s full face close up for the first time in a shot-cross shot with Melissa. While at their table, Georg also sings a children’s song that his deceased mother had sung to him, as the narrator describes his interior state and welling tears. During this intimate scene, which foreshadows the subsequent pivotal moment, Driss and Melissa silently watch Georg singing his past, as they had requested of him. The affective life story of this Jewish-German regenerative minority is the center of attention for Melissa and Driss, the camera, and viewers.

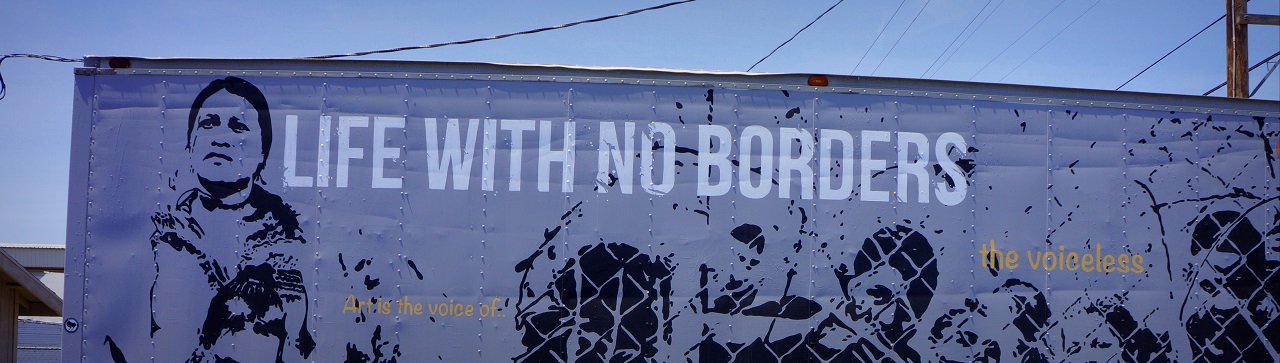

The subsequent revelatory moment interpolates viewers to recognize whose stories have not been told. Tellingly, the scene is generated by an interruption in Georg’s own circles of conversation with the people of the consulates and the cafés, as Marie and her lover Richard obtain passage on a departing ship. The rupture leaves him untethered. Now again recalling Driss, Georg heads to their building. When he knocks on the blue door of their rental apartment it is opened by an unfamiliar person, revealing a crowd of new occupants who appear to be North African migrants. To Georg’s question about Driss and Melissa’s whereabouts, the only response is that they went far away (Fig. 1-3).

Fig. 1-3. Transit (2018), dir. Christian Petzold

Fig. 1-3. Transit (2018), dir. Christian Petzold

This jarring, sudden turn in the plot invites viewers to recognize both the existence and the unarticulated complexity of the stories of those whom Haritaworn dubs “hateful others.” In that these fictional narratives speak to contemporary real-world issues, this alienating twist also encourages viewers to recognize real-world complicities in silencing hateful minorities through attention to more regenerative stories. The touching, grating, circular, ‘white noise’ conversations of the self-absorbed, relatively privileged migrants drown out others; the character Georg and his narrated story are revealed to be regenerative. Meanwhile, the story of this racialized family remains unspoken. Driss’s off-hand invitation to Georg to “travel to the mountains” with Melissa and him is legible only retrospectively as his mother’s age-appropriate description to her son of their planned flight across the Pyrenees—a trip that the strong, healthy, adult Georg had earlier described to others as suicidal. The literally mute character Melissa also remains symbolically voiceless; her probable circumstances as an undocumented migrant of color from North Africa in an about-to-be occupied France do not figure or participate in the public circles of conversation monopolized by the Jewish-German, visually White minority characters. Through a postmigrant aesthetics that juxtaposes these unarticulated and articulated conversations, Transit invites viewers to consider their complicity in maintaining a real-world status quo that continues to oppress hateful migrants while sympathizing with regenerative ones.

Jerichow‘s postmigrant aesthetics also function by drawing in and then disrupting viewer sympathy, but this film set in 2000s Eastern Germany deploys stereotypically Germanic beauty norms in doing so. Viewers position themselves as allies when they sympathize with the two main regenerative protagonists. Subsequently, a revelatory turn at the climax discloses that such sympathy has enabled the continued oppression of the hateful racialized minority character.

Thomas (Benno Fürmann) is an Eastern German Afghanistan war veteran—perhaps dishonorably discharged and certainly fallen on hard times—who inherits his dilapidated family home in the countryside in Saxony-Anhalt near the small town of Jerichow. Struggling to find decent work, Thomas enters the employ of the unattractive, older Turkish-German Ali (Hilmi Sözer), who has built up a successful network of fast-food franchises and married an attractive, younger, German woman. The indebted ex-convict Laura (Nina Hoss) now works with Ali rather than in the bar de nuit where they met and suffers his occasional beatings, jealousy, and alcoholism.

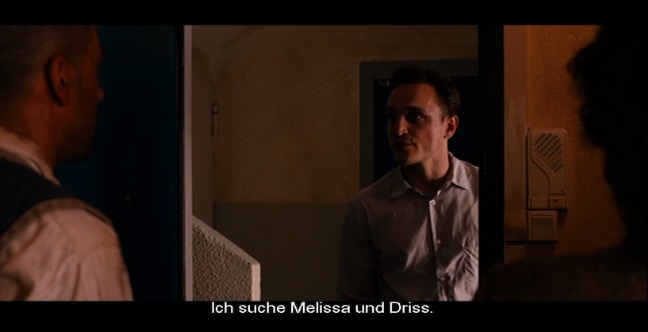

The film works persistently to bring viewers to sympathize with the penniless Thomas and Laura as a couple. The most striking example is the plot’s focus on the sunny morning-after scene at Thomas’s house rather than on Ali’s experiences on his concurrent out-of-town sojourn. A series of full, medium, and close shot-reverse shots of the pair present two beautiful, blonde German bodies of matched size with obvious chemistry (Fig. 5-7).[22] Unlike Ali, who treats Laura harshly, Thomas touches her tenderly and calls out the wounds Ali has left on her body to justify their own relationship and what he terms his love for her. Versions of this sympathy-inducing scene are iterated throughout the film. Indeed, in a foreshadowing of the reveal moment, one situation is instigated by Ali himself, as he very nearly forces his indentured wife Laura and his paid employee Thomas to dance in each other’s arms on the beach (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Jerichow (2008), dir. Christian Petzold

Fig. 4. Jerichow (2008), dir. Christian Petzold

Fig. 5-7. Jerichow (2008), dir. Christian Petzold

Fig. 5-7. Jerichow (2008), dir. Christian Petzold

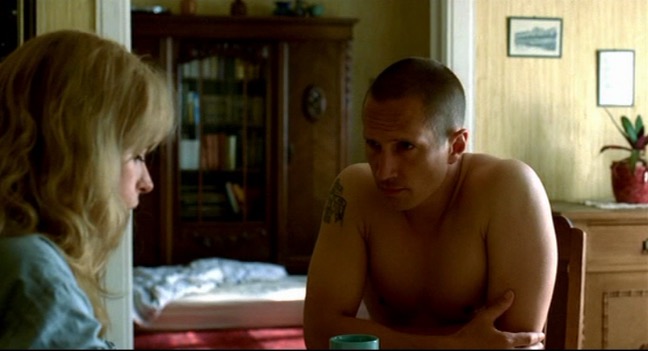

The revelatory scene occurs after Thomas and Laura have decided to murder Ali and start a new life together with Ali’s wealth. In a pre-journey discussion with Thomas, Ali had described a plan to visit his Turkish “Heimat” (“homeland”). (The migrant’s seeming symbolic rejection of Germany here also plays into viewer sympathies with the Germanic lovers.) Ali’s self-censoring prevarication is only revealed upon his return; he secretly visited a heart clinic. Now with a terminal prognosis and weeks to live, Ali tells Laura of his illness for the first time. Seemingly up to this point, the hateful migrant considered silence about his condition strategically protective. He admits that he knows that “he lives in a country that hates him with a wife that he bought.” Then he explains that he has a plan that will secure Laura’s future without him and with Thomas’s help. Ali may have been good-heartedly organizing Laura’s future for quite some time; Fisher reads the beach dance scene this way (130). Critically, the film enables viewers to read Ali’s actions as magnanimous only retrospectively, from its narrative plot pivot, that is, from Ali’s spoken disclosure in this second beach scene. As shown in the screen captures above, Transit‘s revelatory moment relies primarily on visuality to interrupt the silencing of the othered; at Jerichow‘s turning point, the hateful minority’s own voice offers a qualitatively new entrée, here into Ali’s subjective experience as a racialized German.

Fig. 8-10. Jerichow (2008), dir. Christian Petzold

Fig. 8-10. Jerichow (2008), dir. Christian Petzold

While Ali tells his story (Fig. 8-10), viewers are invited to recognize retroactively that his reality has been silenced through the narrative plot focus on the characters of Thomas and Laura and on their increasingly intimate circles of conversation. Further, they can understand that Ali’s protective hush up of his own story by means of a cover-up narrative that matches stereotypical expectations of the hateful other is symptomatic of his precarious positioning. Privy to Thomas and Laura’s mercenary plans, moreover, viewers may now recognize how their sympathy for the redemptive lower working class characters—an “Aryan” Eastern German man and “Aryan” German woman—have furthered inattention to the hateful minority Ali’s oppression. Jerichow loosely remakes The Postman always Rings Twice; intertextual comparison of the good-hearted husband and self-centered, violent lovers in Cain’s 1946 American noir also highlights Ali’s innocence and Laura and Thomas’s guilt.[23]

Phoenix‘s exploration of silencing focuses on privileged circles of conversation that aim to discipline minorities into regenerative minorities, making them assimilable on dominant terms in Kassam’s sense of the Acceptable Muslim (see footnote 11). Phoenix highlights the ways in which the hegemonic society not only determines which minorities function regeneratively, but also seeks to fit minorities into regenerative molds that they have defined for their own benefit.

In this film, the Jewish-German concentration camp survivor Nelly (Nina Hoss) returns to Berlin having undergone reconstructive facial surgery. She finds her non-Jewish, German husband, Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld), who seems not to recognize her. Why? Probably due to his guilt at having denounced her and saved himself, perhaps because he would only wish to find a pre-deportation Nelly who would by her presence also obviate his guilt, or, improbably, because the surgery had been completely botched. Hard up for cash and hoping to emigrate, Johnny quickly conjures a scheme to obtain his putatively dead wife’s inheritance with the assistance of this Nelly “look alike.” Brad Prager has insightfully and in detail argued that the film depicts Johnny’s drawn-out, Pygmalion-style plan as ineffectively led, illogical, and arbitrary. At several points Nelly’s rendition of herself is so superbly accurate as to leave no doubt that she is indeed Johnny’s wife: she remakes her previous appearance with chestnut hair and red dress; she reproduces her handwriting and signature flawlessly; she knows the bench where the two used to sit and mimics how she used to sit on it. At each point, however, Johnny’s confusing, perlocutionary rejections trump mutual, simultaneous recognition of the truth.

What function does this protracted, torturous roleplaying exercise that Johnny so painstakingly and vocally describes, defines, and directs actually serve? This training indeed aims to conjure a fictional Nelly, compelling in look and in performance, untouched by the War, as if just liberated from Weimarian amber. I submit that even more importantly, this indoctrination aimed at conjuring a fictional pre-War Nelly also aims to lastingly silence the real Nelly. As Prager has pointed out, Johnny verbally forecloses Nelly’s few, feeble attempts to articulate her experiences in Nazi Germany (63). It is thus particularly telling that Johnny ends Nelly’s training immediately after she imagines and whispers out loud a narration of her capture that exonerates him (1hr13min—bicycle scene). This voluntarily offered pardon evidences the triumph of Johnny’s heavily scripted training; Nelly has accepted her new regenerative role-playing Johnny’s version of herself. In response to Nelly’s exculpatory discursive monologue, Johnny begins to direct her in the next circle of conversation, with their non-Jewish, German friends.

In this staged, public return, the ‘new’ Nelly who now taciturnly inhabits this regenerative minority role arrives by train at the station. Prager suggests that Johnny and Nelly’s friends are in on the game of self-pardon that also promises Johnny financial benefit. They each play their orchestrated speaking roles of welcome flawlessly, then whisk Nelly off to drinks and discussion at the villa where they had spent many hours together before the War. The incessant and sycophantic chatter of these non-Jewish Germans—some of them former Nazis—circumvent past and present truths and articulate self-serving lies. The closed circle of conversation at the villa preemptively silences Nelly’s wartime experience as Johnny’s discursive verdicts about Nelly’s rehearsals did at his apartment. Their words occlude the wartime reality of Jewish-Germans as hateful others and shape this particular Jewish-German as a regenerative minority for their own ends. This scene and the climatic turning point of the subsequent scene in which—as Prager also argues—Nelly finds her voice, invite viewers to recognize parallels with contemporary, real-world hypocrisies; Phoenix‘s narrative of silencing speaks to contemporary debates about the status of guilt, responsibility, and historical occlusions in a Normalizing Germany post-1990.

At the climactic, pivotal moment (Fig. 11-13), Nelly’s singing voice and her tattooed body speak beyond censure. Performing for their friends at Nelly’s behest, she and Johnny face each other across a piano. Nelly expresses her true self through her unique-as-a-signature vocals while singing “their song.” Further, the lyrics—”Time is so old. And love so brief. Love is pure gold. And time a thief”—are poetic accusations of Johnny’s instrumentalization of her emotions for his benefit: from his vantage point, their “love,” at least this time around, is all about the gold. The penultimate cross-shot sequence alternates between Johnny’s countenance and Nelly’s camp tattoo visible on her bared inner forearm, directly in his line of sight. As their eyes meet, Johnny’s expression marks their mutual recognition of the truth: her distinctive, hallmark oration and this indelible, corporeal articulation of Nelly’s story conclusively expose Johnny’s duplicity, and by extension those of the other non-Jewish, German characters who seek to re-narrate their Jewish-German minority ‘friend’ regeneratively on their terms.

Fig. 11-13. Phoenix (2014), dir. Christian Petzold

Fig. 11-13. Phoenix (2014), dir. Christian Petzold

Phoenix indicates no clear space for Jewish-Germans on their own terms in post-War Germany or, by extension, in contemporary Germany. A comparison of Nelly and her friend Lene highlights this situation. Nelly undertakes Johnny’s project in part because she herself seeks to belie her experiences and Jewishness and to reassimilate to mainstream German society. The film juxtaposes Nelly’s accommodating stance with that of the non-accommodating Lene. Lene is angry at and unforgiving of German actions during and post the Nazi period. She commits suicide when Nelly chooses Germany and Johnny over Israel and her. Lene could be read as embodying a hateful minority; at the same time, she precludes interactions with those who would subjectify her into this status. Lene’s unrelenting, even dogmatic stance and her suicide suggest a present-day critique of what would become an Israeli state grounded in anti-postmigrant sensibilities. Yet Lene’s forthrightness also helps Nelly reclaim her voice. After all, it is thanks to Lene that Nelly learns the truth of Johnny’s divorce that left Nelly legally exposed. This discovery shortly before her debut in their friendship circle turns Nelly away from Johnny, although she does not use the pistol that Lene also provided her. Instead, Nelly rejects both the roles of regenerative and hateful other. After revealing her story, Nelly turns from the piano and disappears through the open door into a sunlit-white garden in a final soft dissolve; her future painfully unclear, although potentially bright (Fig 14).

Fig. 14. Phoenix (2014), dir. Christian Petzold

Fig. 14. Phoenix (2014), dir. Christian Petzold

As Transit engages and illuminates current migration injustices and Jerichow post-unification racism (Miller), Phoenix intervenes in debates around German Normalization and concomitant revisions of German history. Understood in relation to these contemporary questions, the films’ postmigrant aesthetics articulate realities of European heterogeneity through fiction. They engender viewer sympathies with privileged regenerative others and then also invite critical reflection on how such sympathy can advance chauvinism vis-a-vis hateful minorities. Such reflections also prompt scrutiny of progress narratives of regeneration expressed in dominant circles of conversation. In these manners, the works also invite recognition of multiplicities of oppressions. Finally, the melodramas articulate perils of silencing in real-existing but not fully recognized postmigrant Europe, even with an aspirational postmigrant Europe on the horizon. In so doing, Transit, Jerichow, and Phoenix warn against premature affirmation of an extant postmigrant Europe given that oppressions of many of its political subjects continue.

Works Cited

Abel, Marco. The Counter-Cinema of the Berlin School. Camden House, 2013.

————. “Intensifying Life: The Cinema of the “Berlin School”.” Cineaste, vol. 33, no.4 (Fall 2008). https://www.cineaste.com/fall2008/intensifying-life-the-cinema-of-the-berlin-school.

“afropean.” Urban Dictionary, 2012. Web. 3 May 2021.

Haneen, Maikey. Beyond Propaganda: Reorienting Anti-Pinkwashing Organizing. A Community Conversation with alQaws’s Haneen Maikey and Nas Abd Elal and Adalah Justice Project’s Sumaya Awad. Adalah Justice Project. 22 October 2020. https://www.adalahjusticeproject.org/equalityreport/2020/10/27/beyond-propaganda-reorienting-anti-pinkwashing-organizing. Webinar.

Baer, Hester. “Affectless economies: the Berlin School and Neoliberalism.” Discourse, vol. 35, no. 1, 2013, pp. 72-100, 128.

Biendarra, Anke S. “Ghostly Business: Place, Space, and Gender in Christian Petzold’s Yella.” Seminar: A Journal of Germanic Studies, vol. 47, no. 4, 2011, pp. 465-478.

Castro, Joy. “Intimate Terrains: Contemporary German Cinema, Migration, and the Films of Aysun Bademsoy.” Senses of Cinema, no. 92, October 2019, http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2019/feature-articles/intimate-terrains-contemporary-german-cinema-migration-and-the-films-of-aysun-bademsoy/.

Cattien, Jana. “What Is Leitkultur?” New German Critique, vol. 48, no. 1 (142), 2021, pp. 181–209.

Chakraborty, Rhituparna. “RTG Minor Cosmopolitanisms.” University of Potsdam, 21 January 2021, https://www.uni-potsdam.de/en/minorcosmopolitanisms/.

Cooke, Paul and Stuart Taberner, editors. German Culture, Politics, and Literature into the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Normalization. Camden House, 2006.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari [1975]. Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Fisher, Jaimey. Christian Petzold. University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Habermas, Jürgen. Die Normalität einer Berliner Republik. suhrkamp, 1995.

Haritaworn, Jin. “Queer Injuries: The Racial Politics of “Homophobic Hate Crime” in Germany.” Social Justice, vol. 37, no. 1 (119), 2010, pp. 69-89.

————. Queer Lovers and Hateful Others: Regenerating Violent Times and Places. Pluto Press, 2015.

Hayward, Susan. Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts. Routledge, 2000.

Heywood, Andrew. Global Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Hosek, Jennifer Ruth. “Buena Vista Deutschland. Nation, Race und Geschlecht in Filmen von Wenders, Gaulke und Eggert.” Berliner Debatte Initial, vol. 1/2, 2008, pp. 96-110.

————. “Present History under Surveillance: Petzold’s The Gespenster Trilogy.” The Place of Politics in German Film, ed. Martin Blumenthal-Barby, Berghahn, 2014.

————. “‘Subaltern Nationalism’ and the Anti-authoritarians.” German Politics and Society, vol. 85, no. 26.1, 2008, pp. 57-81.

Imogen, Sara Smith. “Neither Here Nor There: Always leaving or being left behind, the refugee protagonists of Christian Petzold’s Transit circulate on the tides of war and history.” Film Comment, March-April 2019, https://www.filmcomment.com/article/neither-here-nor-there/.

Kassam, Shelina. “Rendering Whiteness Palatable: The Acceptable Muslim in an Era of White Rage.” Journal of Critical Race Inquiry, vol. 7, no. 2, 2020, pp. 74-96.

King, Alasdair. “The Province Always Rings Twice: Christian Petzold’s Heimatfilm noir Jerichow.” TRANSIT, vol. 6, no. 1, 2010, p. electronic, doi: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/3r61h87r.

Landry, Olivia. “The Beauty and Violence of Horror Vacui: Waiting in Christian Petzold’s Transit (2018).” The German Quarterly, vol. 93, no. 1, 2020, pp. 90-105.

————. Movement and Performance in Berlin School Cinema. Indiana University Press. 2019.

Lionnet, Françoise and Shu-mei Shih. Minor Transnationalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

Miller, Matthew. “Facts of Migration, Demands on Identity: Christian Petzold’s Yella and Jerichow in Comparison.” German Quarterly, vol. 85, no. 1 (Winter), 2012, pp. 55-76.

Nayman, Adam. Transit. 1 March 2019, http://www.reverseshot.org/reviews/entry/2488/transit.

Nelson, Max. “”Our Contemporary Winds”: Christian Petzold’s Transit.” Salmagundi, vol. 204/205, no. Fall 2019/Winter 2020, pp. 38-48, 203.

Petzold, Christian. “Christian Petzold discusses Transit.” Interview by Elena Lazic, Seventh Row, 22 March 2019, https://seventh-row.com/2019/03/22/christian-petzold-transit/.

————. “Christian Petzold on Transit, Kafka, His Love for Den of Thieves and More.” Interview by Vibram Murthi, Roger Ebert.com, 27 February 2019, https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/christian-petzold-on-transit-kafka-his-love-for-den-of-thieves-and-more.

————. “The Cinema of Identification Gets on my Nerves: An Interview with Christian Petzold.” Interview by Marco Abel, Cineaste, 2008, https://www.cineaste.com/summer2008/the-cinema-of-identification-gets-on-my-nerves.

————. “Interview: Christian Petzold.” Interview by Jordan Cronk, 28 February 2018, https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/berlin-interview-christian-petzold/.

Pitts, Johny. Afropean: Notes from Black Europe. Penguin, 2019.

Prager, Brad. Phoenix. Camden House, 2019.

“RAID (French Police Unit).” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 24 April 2021. Web. 4 May 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RAID_(French_police_unit).

Rentschler, Eric. “From New German Cinema to the Post-Wall Cinema of Consensus.” Cinema and Nation, edited by Mette Hjort and Scott MacKenzie, Routledge, 2000, pp. 260-277.

Sicinski, Michael. “Once the Wall Has Tumbled: Christian Petzold’s Jerichow.” CinemaScope, vol. 38, 2009, http://www.cinema-scope.com/cs38/feat_sicinski_jerichow.html.

Xiang, Zairong, editor. minor cosmopolitan: Thinking art, politics, and the universe together otherwise. Zürich and Berlin: Diaphanes, 2020.

[1] Originally organized for the Central European Studies Conference 2020 as part of the European Studies Research Network, University of British Columbia’s Department of Central, Eastern and Northern European Studies hosted this virtual event

[2] The Universität Potsdam, HU Berlin and FU Berlin are home to the Research Training Group Minor Cosmopolitanisms (https://www.uni-potsdam.de/en/minorcosmopolitanisms/). Were I to attempt a genealogy of minor cosmopolitanism, I would include Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature, Françoise Lionnet and Shu-mei Shih’s Minor Transnationalism and Zairong Xiang’s anthology minor cosmopolitan: Thinking art, politics, and the universe together otherwise.

According to the Urban Dictionary, Afropean is a “term to describe the trans-cultural influences of (..usually…) mixed race individuals, or members of the black diaspora living in Europe” (“afropean”).

Pitts writes, “When I first heard it, it encouraged me to think of myself as whole and unhyphenated: Afropean. Here was a space where blackness was taking part in shaping European identity at large” (i).

[3] For a recent treatment of “leading culture,” one that argues that this notion necessitates disavowal of German colonialism, see Cattien.

[4] Utopia is an overdetermined concept and yet I hope that its deployment here clarifies rather than confuses. I use the term in the utopistics tradition of thinkers such as Ernst Bloch, Jürgen Habermas, and Immanuel Wallerstein. Such imaginings of better worlds are not prescriptive, but energizing and aspirational. The realizations of these worlds are possible rather than inevitable. Sustained strivings in their direction tend to improve more proximate future worlds. Although Römhild shows that it is really-existing, postmigrant Europe is also utopian because it is not commonly recognized. The widespread equity and equality that could inhere were it commonly recognized remain utopistically aspirational.

[5] At the suggestion of my editor, I drop the quotes around regenerative and hateful in the remainder of this article, as I am deploying these terms according to Haritaworn’s technical definitions. In Jerichow, the White protagonists function regeneratively. Although they are not technically minority in terms of racialization, they hold subordinate positions due to low socio-economic status and, at least Thomas’s case, East German background. Women are often considered minorities due to their subordinate positionings.

[6] By circles of conversation, I mean persistent, monologic and dialogic flows of discourse that articulate some stories and suppress others. This term is inspired by the theme of the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada Congress 2019 held at University of British Columbia June 1-7, 2019: Circles of Conversation. I thank the audience for their helpful comments at my talk in the joint panel of the Canadian Association of University Teachers of German (CAUTG) and The Coalition of Women in German (WiG).

[7] See also: Haritaworn, “Queer Injuries.”

[8] By silencing here, I mean that the subjectivity of the hateful minority character has not been articulated, typically because they do not speak and the camera does not register their expressions, actions, or experiences except in support of a primary character or plotline. A perspicacious reader helpfully suggested the term “narrative neglect” rather than silencing to describe such “exegetic directorial techniques that manipulate audience sympathies.” The phrase “narrative neglect” does indeed usefully highlight that the phenomenon sometimes works through plot turns that tell the stories of some characters rather than the stories of others. In these cases—whether we consider the director, films, or both as creators—the plots of the narratives do not actually precisely neglect the stories of the hateful minorities but rather hush them strategically; their reveals at the crescendos of the plots have more effect. Therefore, in the final analysis, I still prefer silencing. The term silencing also gains traction through its resonance with critical notions of voice and voiceless. Feminist, postcolonial, and Marxist theory (e.g., Gramsci’s and Spivak’s subaltern) speak eloquently on silencing. E.g. see Hayward for sections on melodrama and postcolonial theory.

[9] By chauvinism, I mean: “the irrational belief in the superiority or dominance of one’s own group or people, who are seen as strong and virtuous, while others are considered weak or unworthy” (Heywood 166).

[10] Cf. Hosek, “Buena Vista Deutschland. Nation, Race und Geschlecht in Filmen von Wenders, Gaulke und Eggert.”

[11] For instance, AlQaws for Sexual and Gender Diversity in Palestinian Society Director Haneen Maikey uses the term “pinkwashing” to describe “presenting the [Israeli] state as a ‘progressive’ and ‘gay-friendly’ haven” to deflect attention from its violent practices towards Palestinians.” Here, progressives and gays function regeneratively against the hateful Palestinians. The speakers in the webinar argue that another feature of pinkwashing is the systematic erasure of the queer Palestinian movement. Here, progressives and gays also function as regenerative. Along similar lines, Shelina Kassam shows that the figure of the “Acceptable Muslim” obscures entrenched Islamophobia in a putatively liberal and open Canada. Cf. Kassam.

[12] Cf. Hosek, “‘Subaltern Nationalism’ and the Anti-authoritarians.”

[13] After the formal end of the Cold War and Unification, Germany shifted from more Europeanist and pacifist to more nationally minded and aggressive. Literature on this phenomenon, dubbed “Normalization,” is legion. Three most useful early texts are: Habermas, Jürgen. Die Normalität einer Berliner Republik; Rentschler, Eric. “From New German Cinema to the Post-Wall Cinema of Consensus”; and Cooke, Paul and Stuart Taberner, editors. German Culture, Politics, and Literature into the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Normalization. Discussions with Pia Brinkschulte and other students in my German 317 Fall 2015 course generated this insight about Normalization and Phoenix.

[14] Cf. Miller.

[15] While it escapes the scope of this article for me to explore Michael Haneke’s Happy End (2017), this melodrama’s postmigrant aesthetics deploys a surprising plot turn to reveal the travails of migrants in Europe.

[16] Cf. Abel; Baer; Biendarra; Fisher; Hosek, “Present History under Surveillance: Petzold’s The Gespenster Trilogy”; Petzold, “The Cinema of Identification Gets on my Nerves: An Interview with Christian Petzold.”

[17] Cf. Petzold, Christian. “Interview: Christian Petzold”; —. “Christian Petzold on Transit, Kafka, His Love for Den of Thieves and More.”

[18] On waiting in Transit, see Landry, “The Beauty and Violence of Horror Vacui: Waiting in Christian Petzold’s Transit (2018).” On tension, see Nelson. On waiting and non-places in Petzold’s work, see Imogen.

[19] The narrator is eventually revealed to be the barman in the pizzeria where most of the regenerative minorities commune. Petzold attributes his decision to use this narrative device to his own open discussion with a barman (Petzold, “Christian Petzold on Transit, Kafka, His Love for Den of Thieves and More”). Casablanca features the immortal Bogart.

[20] At the suggestion of one of my careful reviewers, I henceforth abridge the term “normative attractiveness” for the sake of prose flow; this is shorthand. The climactic pivot hinges on its reveal of White lookist privileging.

[21] Cf. Nayman.

[22] Cf. Sicinski.

[23] See King.