Displacement vs. Mobility; or, Who Owns the World: An Aesthetic Inquiry into Infrastructure, Comm on Possession, and Violence in Karim Aïnouz’s Documentary Film Central Airport THF (2017)

by Astrid Deuber-Mankowsky

TRANSIT vol. 14, no. 1

Translated by Ross Shields

Abstract

Central Airport THF is a documentary film about the temporary housing of refugees in the halls of the former Tempelhof Airport, located at the edge of Berlin’s Tempelhofer Feld. As if by accident, the director contrasts the arrested life in the adapted shelter to the mobility of life in the politically contested Tempelhof Park adjacent to it. Beginning with the specific locality of Central Airport Tempelhof, its architecture, history, and current use as refugee housing, the film employs aesthetic means to render an affectively knowable violence that extends to the very ground of what we call ‘infrastructure.’ The analysis of these aesthetic moments leads to questions that are only rarely addressed in the context of displacement and asylum, but are no less central to the relationship between displacement and mobility: What is common possession? Who owns the world? Does the world fall—can it even fall—under the categories of property or ownership?

Introduction

Central Airport THF is a documentary film about the temporary housing of refugees in the halls of the former Tempelhof Airport, located at the edge of Berlin’s Tempelhofer Feld. Over the course of a year, from May 2016 to May 2017, the director follows the daily lives of two figures: an eighteen-year-old Syrian refugee named Ibrahim Al Hussein and the somewhat older Qutaiba Nafer, a professional translator who fled Iraq. Both men want to rebuild their lives after being displaced. Both are forced to wait. Director Karim Aïnouz places their arrested lives in the adapted airplane hangar in striking contrast to the mobility of the neighboring Tempelhof Park. While those in the terminal wait, those on the former airport’s landing strip take advantage of the vast space for recreational activities. They enjoy various forms of exercise such as electric biking, Nordic walking, skateboarding, windsurfing and kitesurfing, and use vehicles of different sizes such as e-scooters, pedal cars, gocarts and Segways.

The history of Tempelhofer Feld and the airport play a decisive role in the film, showing the relationship between invisibility and visualization, which is central to the aesthetic investigation of infrastructure and violence [Gewalt]. My intention is not, as one might suppose, to reveal the invisible components of technical infrastructure and their logistics: the cables and pipes hidden in ceilings, in walls, and on the floor of the ocean. Nor am I concerned, at least not primarily, with the hidden data streams that organize and control both human affects and individual movements within large crowds. Instead, I want to show how Aïnouz, starting out from the specific locality of Central Airport Tempelhof, its architecture, history, and present, employs filmic means to render hidden violence—that reaches to the very ground of the airport’s infrastructure and the history of its construction—visible, that is knowable. What the film reveals, on both affective and aesthetic levels, is how this violence extends throughout the history of what we call infrastructure, a history that is nevertheless predated by that violence.

I understand affect in the sense of Deleuze and Guattari, who conceive it in aesthetic (and not psychological) terms, hence, as a phenomenon of expression.[1] In opposition to aesthetic systems that define works of art as representations, Deleuze and Guattari conceive of works of art as preserved sensations, which they ultimately define as “beings of sensation” (êtres de sensations).[2] According to Deleuze and Guattari, works of art are created when an artist succeeds in materializing perceptions and affects in an (often transitory) state so that they can exist independently of empirical sensations as beings of sensation. I argue that such “beings of sensation” can be discerned in Central Airport THF, and will reveal how they correspond to the violence inscribed in the development of infrastructure as such. The analysis of these aesthetic moments leads us to questions that are only rarely addressed in the context of displacement and asylum, but are nevertheless central to the relationship between displacement and mobility: What is common property? Who owns the world? Does the world fall—can it even fall—under the categories of property or ownership? Immanuel Kant addresses precisely these questions in his treatise on the “Metaphysical First Principles of the Doctrine of Right” in context of his justification of universal human rights[3]. I will show the ways in which Kant not only accepts violence, but also uses it to support his concept of property rights and the right to common property, and to define man as an ambivalent natural and rational being.

The technical concept of infrastructure was introduced in France in the second half of the nineteenth century in the context of railroad construction, where it designated the preparation of land and soil to support heavy rails. Infrastructure was thus a presupposition not only for the networking of transportation and supply systems but also for the industrialization and concomitant colonialization of the world, which was carried out rapidly in the second half of the nineteenth century. It is significant that the English word infrastructure refers to the aggregate of buildings, constructions, and equipment that support the mobilization of armies. Necessary for the operation of airports, for the establishment of cultural, educational, transport- or border-security systems, and even for the supply of energy, water, and foodstuffs, infrastructure requires financing through state funds or private investments. It is therefore closely related to questions that arise concerning the division of land and the relationship between private and public interests, and, accordingly, between politics and economy.

Central to all of these questions is the concept of ownership and the relations between property, rights, law and violence.[4] After all, the figure of the possessor is “founded”—to borrow Kant’s formulation—on the “common possession of the land,”by which we must understand, as I will later explain, the idea of an “original community of the land.”[5] Kant was the first philosopher to provide a systematic justification for a state and legal order that would ensure a unified society and permanent safeguard to peace. For Kant, the primacy of the right of ownership is not only the only condition of civil society—which is for him a society oriented toward the peaceful resolution of conflict—but also a condition of the idea of universal human rights. The “original [ursprüngliche] community of the land” is—as Kant emphasized—an idea, which may have an “objective (legal-practical) reality, but must never be confused with the “primordial” [uranfänglichen] community whose existence could be verified by empirical evidence. Yet, how does the historical reality of relations of ownership and possession, with their demarcations, inclusions, and exclusions, relate to the “idea of an original community of the land”? And how are law and violence situated in relation to this foundation, to this grounding, of property in the idea of a “common possession of the land”? Finally, what role does justice play in all of this?

Central Airport THF raises precisely these questions with its specific aesthetic, which is informed by formal decisions and techniques including camera work and movement, framing perspectives, mise-en-scène, close-up shots, voices, and sound. As a specific shaping of space and time, of light and sound, the massive building’s architecture also plays a decisive role in the film’s aesthetic.

Queer aesthetics and architecture

Karim Aïnouz studied architecture at the University of Brazil before moving to the United States during the 1990s to study film at New York University. Born to a Brazilian mother and an Algerian father, he spent a considerable portion of his life in Berlin. Between 1989 and 1992 he worked as an assistant to Todd Haynes and was involved in the production of the experimental film Poison (1991). With Poison, Haynes co-founded the queer cinema movement at the height of Act-Up and the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York. This experience together with his experimental filmmaking went on to influence Aïnouz’s later work. His first feature length film, Madam Satã, which premiered at Cannes in 2002, tells the life of the Brazilian transgender and underground drag performer João Francisco dos Santos. His two subsequent films, Suely in the Sky (2006) and I Travel Because I Have To, I Come Back Because I Love You (2009), which was co-directed with Marcelo Gomes, were set in Brazil’s poverty-stricken north. In both films, the vastness of the arid land plays an important role in the story of two men fighting against precarious conditions in which they live. Praja da futuro (2014) tells the story of a queer love affair spanning two continents and two cities, from Fortaleza, a city on the East coast of Brazil, to Berlin. In his earlier work, mood and atmosphere, especially feelings connected to the environment, the city, and its architecture, to the landscape and its light, together with movement across boundaries, all play important roles. His 2019 film, The Invisible Life of Euridice Gusmao, depicts the lives of two sisters in 1950’s Rio de Janeiro who are violently separated by a father intent on breaking their will. The film thematizes the hypermasculinity of Brazil in a way that presents the sisters’ lives as a waking, through a series of intensive images embedded in the sound of the city which carry the sisters’ quiet resistance into the political reality of contemporary Brazil. Aïnouz also writes screenplays and shoots experimental videos, including a contribution to the 3D film Cathedrals of Cultures (2014). Focusing on one prominent large building each, Aïnouz, Wim Wenders, Michael Glawogg, Michael Madson, Robert Redford, and Margreth Olin provide filmic answers to the question: If these walls could talk, what would they say? Through a sequence of tranquil shots, Aïnouz’s segment presents Paris’s Centre Pompidou as a “living, breathing culture machine.”[6]

As in his previous work, Central Airport THF starts out from Aïnouz’s interest in architecture and the relationship between buildings and landscapes, and in history as a meshwork of living relations. As a result, the film presents the airport and its surroundings, together with its architecture and infrastructure, as a document of history that is inscribed in the building, in which it participates and which it transcends at the same time. As we will see, this extension of agency from human actors to architecture, infrastructure, and the surrounding landscape puts into question not only the right of ownership, but also the very representation, tied up with that right, of the body itself as property. The right of ownership, as can be seen in Kant, is connected with the idea of human being as a rational being who disposes of his body as of his property. This is particularly clear in Kant’s definition of marriage as a contractual “union of two persons of different sexes for the life-long, mutual possession of their sexual properties.”[7] And it is here that the film reveals its commitment to the tradition and concerns of queer cinema.

The airport, the field, the refugees

Tempelhof Airport lies in the center of Berlin. It was constructed in 1923 on Tempelhofer Feld, which was controlled by the army in the eighteenth century and used for military parades and exercises. The district of Tempelhof purchased the grounds in 1910, authorizing construction on parts of it. But the resulting airport, which was completed in 1928, was soon recognized as too small. In 1934, Ernst Sagebiel, one of the most important architects of National Socialism and a member of the NSDAP and SA, set to work expanding the airport as “World Airport,” according to Hitler’s plans. In fact, Tempelhof was the first airport that would fulfill all of the infrastructural requirements of a major airport. However, because of the war, the soon-to-be-completed airport was, as of 1940, used exclusively by the arms industry. Thousands of forced laborers were displaced there in order to service and assemble dive bombers, living in camps and quarters that were distributed across the entire field.

Flight operations resumed immediately after the war. During the Berlin Blockade from June 1948 to May 1949, Tempelhof Airport received international attention due to the so-called raisin bombers, which landed there while supplying West Berlin with food and supplies. In this way, the Cold War eclipses the period of National Socialism here as well.

Today, Tempelhof Airport first brings to mind neither National Socialism nor the Berlin Blockade. Instead, one recalls the successful resistance of the Berlin public to the zoning plans of the Berlin senate after air traffic was permanently discontinued in 2008. The vast plain of Tempelhofer Feld, open to the public in its full imposing expanse, serves as a kind of memorial to the success of resistance. The Senate’s plans stipulated that the grounds be made available to both public and private investors for the construction of offices, apartments, and shops. To prevent the concomitant privatization, commercialization, and gentrification of the space, protesters and activists organized demonstrations and occupied the grounds. They received broad public support for their efforts. This pressure resulted in the Senate temporarily setting aside Tempelhofer Feld for use as a public park. The opening of the Tempelhofer Feld—previously inaccessible, with its airstrips, imposing emptiness, and borderless expanse—felt like a revolution. Visitors flowed in, submitting themselves to the sublime aesthetic of the empty expanse in the middle of the city, perhaps only unconsciously aware that it was the very place where Albert Speer orchestrated the gigantic spectacle of Hitler and the NSDAP’s first military parade. What a contrast to Hitler’s shaped masses this new spectacle presented, with its scattered individuals spread out across the great plane, vulnerable and small on their bicycles and other modes of transport! Tempelhofer Feld soon became one of the biggest tourist attractions in the city. In 2011, a citizens’ initiative organized the 100% Tempelhofer Feld referendum, which aimed to permanently preserve the entire grounds for public use. The vote took place in 2014 and was approved by a large majority of the Berlin populace. And so, the former airport, along with its infrastructure, was converted permanently into an immense, public, and nature-oriented recreational area.

When Aïnouz decided to make a film about Tempelhof Airport in 2015, it was the place’s specific history, and above all its recent history, that fascinated him. As he explains in a 2019 interview,[8] Tempelhofer Feld with its expansive meadows and green spaces providing refuge for animals, birds, bees, insects, and foxes—struck him as a utopian place with high imaginative potential. The empty airport and landing strips seemed to indicate a historical shift in the field’s history and intended purpose: the real possibility of seizing and appropriating an enormous piece of land by and for the people. The seemingly infinite space now stood for the creation of a vast commons in the middle of the city, invoking a new history beyond capitalism and fascism. The film was intended to document this moment. But it turned out to be quite different.

Aïnouz’s film plans coincided with the first wave of refugees to Germany in October 2015. In late October 2015, the hangars were repurposed to serve as temporary emergency housing for the refugees. The presence of the refugees and the use of the former airport hangar to house those refugees also changed public perception of the airport and of the bordering Tempelhofer Feld. Aïnouz and his team first observed the changes in the airport and carefully built relationships with its new inhabitants. They finally received a film permit and began shooting in May 2016, continuing until June 2017.

An airport is a place of transition and transit, a passage and a border. At one point in the film, Ibrahim Al Hussein, the young man from Syria, relates how some of those who arrived in emergency housing in late 2015 were initially dismayed, fearing that they had been sent back to their places of origin. It took them some time to realize that the airport had been repurposed and that they would now be living in it. An airport is also a place of transition and transit in the sense that it invites—and therefore provokes—dreaming of other places. The people physically waited, not allowed to move freely, yet they remained mobile in their fantasies, in their dreams, and in their stories.

The film documents the presence and lives of refugees in the hangars immediately bordering on Tempelhofer Feld, whose lines of sight lead into a seemingly infinite sky. In doing so, it raises and renews the question of the relationship of historical ownership to demarcations of an “objective idea” of a “common possession of the land” and the “idea of an original community of the land.”[9] This all the more to the extent that Kant connects the foundation of property in the idea of an ‘original community of the land per se’ to the universal human right of people “to stay there, wherever nature or contingency (without their willing it) has placed them.”[10] For Kant, this universal right to a place in the world derives from the fact that the surface of the earth as a spherical surface is infinite in itself and yet uniform. The world as a sphere corresponds via this formal connection of unity and infinite variety with the idea of a human community, which as universal is more than the sum of all individual wills. And thus more than the sum of all the places that people occupy with their bodies on earth. The idea of an “original community of the land” stands for Kant, to put it differently, in a conditional relation to the existence of a universal will, to which in turn the universal human rights and the observance of these rights are linked. But how can one reconcile this abstract, conditional relation, in which all people are equal, which is located only in the universal, with historical conditions that are so different for individual people?

Central Airport THF

The film begins with a black screen accompanied by the dampened sound of airplanes taking off and landing in the distance. After a moment of hesitation, the quiet voice of a young man begins to speak quietly in Arabic over the background noises. He describes his first impressions upon arriving in Berlin at the turn of 2016 when the streets were still festooned with Christmas decorations. It is an excerpt from the diary that Al Hussein began writing when he first arrived in the city. We read the translation in white letters against a black background. As the voice calmly relates, these first hours were full of joy. Multilingualism, scenes of translation, of comprehension, and German class became an important part of the daily lives of refugees. The film communicates the complexity and tension of this situation through the interplay of its visual and auditory dimensions, of text, moving images, and sound.

The impression of frailty and vulnerability in Hussein’s voice is amplified by a hard cut to a panoramic shot, in central perspective, of the airport’s façade, where the illuminated letters “Zentralflughafen” hang over the entrance. The camera remains still, which intensifies the impression of monumentality before a second cut to a view of the entrance hall, again shot in central perspective. The persisting sound of take-offs and landings is replaced by the resonant hum that is typical of large rooms, as the soft yet piercing sound of a trumpet infuses the image. We hear a female voice describing the history of the airport to a group of quiet visitors and, by extension, to the film’s audience. The voice continues over a sequence of carefully composed static views of every nook and cranny in the hall. The camera accompanies the tour but never comes too close to the group, but instead remains static and at a distance. An impressive view of a picture hanging on a wall reveals an aerial perspective of the airport as an extension of the Platz der Luftbrücke, from which Columbiadamm and Tempelhofer Damm extend along the airfield like two sides of a triangle. As the group takes photos, the woman’s voice explains that the airport contains air raid shelters that were used during WWII.

The first tones of the overture to Wagner’s Rienzi, der letzte der Tribunen resound as soundtrack over the images of the hall. As the music swells, we witness a sequence of shots: the group descends into the air-raid shelter, looks out through a window from inside the airport, and then gazes out from the roof at the apparently infinite expanse of Tempelhofer Feld. Finally, we see an impressive panorama view of the airport from far above. From here, everything appears very small indeed. This does not change with the next sequence of shots, which reveal, to the rhythm of Wagner’s Rienzi, unusual and always strongly perspectival views in and of the architecture, concluding in an extreme, eye-level long shot from the airfield of the airport’s rear exit, with children on segues riding in circles the foreground. A certain perplexity is engendered by the contrast between the tiny, helmeted humans on their segues, on the one hand and the monumentality of Wagner’s music and the airport’s architecture, on the other. Aïnouz’s static camera and long and extreme long shots culminate in a drones-eye-view panorama over the airport and into the city. The contrast between the small helmeted people on their Segways and the monumental claim of the Wagnerian music in connection with the strictly central perspective architecture of the world airport, lets the built-up claim of great power disintegrate. How do history and the present connect via infrastructure and architecture?

The contrast inscribes a question in the image. The shot is an affection image, which, as Deleuze writes, “regards the potential or quality as such, that is, as expressed.”[11]As Deleuze has shown, the movement of expression was typified in early film by the close-up of the human face, that’s why he called the close-up of the human face affection image. But he emphasizes that a landscape or its architecture can also become a face, as is the case here. Thus, a landscape can mutate into a formal movement of expression when it has the aesthetic form of a unity that combines the two poles of reflective unity and intense micro-movements, as we know from the close-up of a face. This idea is underlined by Wagner’s music in the background, which seeks to immerse the soul in infinite spaces.

It is no coincidence that the connection between unity and the infinitely small micro-movements that characterize Deleuze’s affection image recalls Kant’s association of the earth represented as a sphere, which synthesizes unity and infinite variety. “Because,” Kant writes, “if it [ the earth, ADM ] were an infinite surface, then people might disperse themselves across it in such a way, that they would never come together as a community, which would invalidate the latter as a necessary consequence of their existence on earth.”[12] In other words, Kant makes the existence of human community, which is founded in the idea of universal humanity, dependent on the representation of the earth as a sphere. It is different for Deleuze, for whom the affection image culminates in the provocation of two questions: “What are you thinking about” and/or “What do you feel?”[13] Here Deleuze refers to Descartes, who defines amazement [Staunen] as that which presents a maximum of reflected unity, invoking the English verb “to wonder” for its preservation of the connection between amazement and thinking. The affection image forms a subject that wonders and, in the best case, begins to think. The documentation of life in the hangar begins only after problematizing and conveying the history of the location in this way.

Life in the hangar and life in Tempelhofer Feld

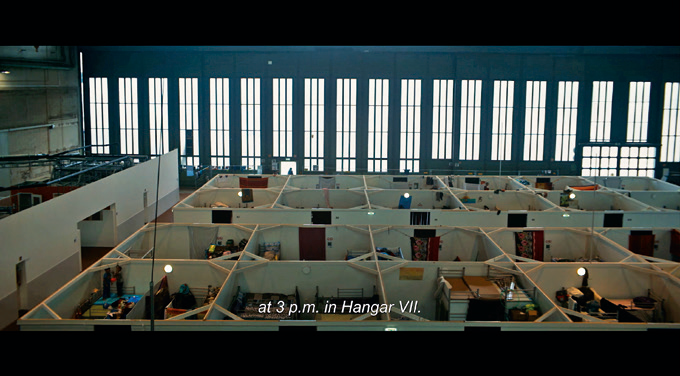

The emergency housing set up in fall 2015 in the hangars of Central Airport Tempelhof was only meant to be temporary. Instead of lasting for two weeks, it lasted for more than two years, and accommodated up to 3,000 people. The film depicts the year from May 2016 to May 2017, showing without comment, quietly and distantly, how the airport’s existing infrastructure has been used for new purposes. The scanners that used to check travelers and luggage through the airport’s security checkpoint are seamlessly repurposed for inspecting refugees and checking their few belongings. The former offices are used for registering arriving refugees. A variety of languages prevail: Russian, Arabic, German, all in need of translation. The intercom that once told passengers to proceed to their gates now asks the first arrivals, in the same friendly tone and in a variety of languages, to proceed to another hangar for mandatory vaccinations. The reverberation of the huge hangar melts into a background noise, more felt than heard, that drowns out all these voices and negates any silence, even when it is dark: the lights of the entire hangar are turned off in the evening with a loud bang, above the open sleeping and living containers and thus for everyone.

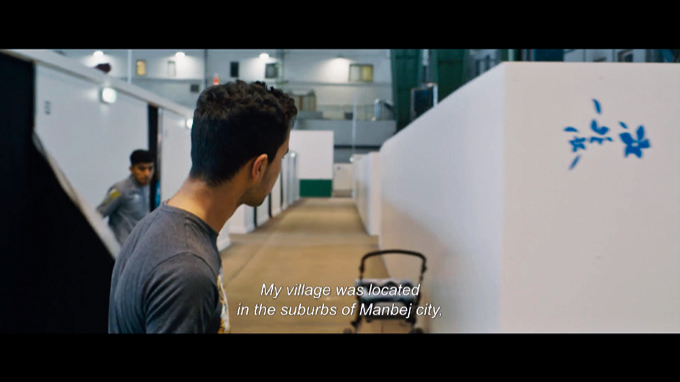

The film depicts life and waiting in the hangars on several formal levels that are interwoven. The main narrative thread consists of notes from Ibrahim Al Hussein’s diary, which he reads aloud throughout the film. We hear his voice as a voiceover, the only voiceover in the entire film. Sometimes we see him in the frame as we hear his voice, sometimes his voice seems detached from his person, superimposed on the landscape of Tempelhofer Feld. As Hussein talks about his hometown, his friends, and his family who stayed behind in Syria, we learn that he writes to remember. He describes his impressions of the new place and its inhabitants, the differences, and his experiences waiting for a decision on his asylum application. At one point, he describes his forced displacement and the moment he said goodbye to his mother.

In February 2017, towards the end of the film, we learn that his application was successful and that he is leaving Tempelhof after more than a year to move into his own apartment. He wants to improve his German and attend a vocational school to become a mechanic. We learn about the bureaucratic infrastructures that make life so precarious while seeking asylum, about waiting and the passing of time. In some scenes, we see Hussein talking with his friends, attending a German course, participating in a really miserable Christmas party organized in the hangar for the refugees, and celebrating New Year’s Eve on the roof of the airport with the fireworks over Berlin. Sometimes we see him jogging, sometimes we see him moving slowly among the visitors who spend their free time in Tempelhofer Feld, coming and going as they please. We see how alien he feels among them, how no interactions take place.

A second formal level consists of the scansion of the documented period of time as a succession of twelve months and four seasons. At intervals of four to fifteen minutes, a faded-in black screen and the voice of Ibrahim announce the new month in Arabic, the translation of which we see in white letters on the black screen. We follow the rhythm of the seasons, the change of light and the weather, and the transformation of life in the park, which is shown in perfectly composed images. Once, on a late autumn evening, we follow the park’s guards as they drive their cars in the dark across the airstrips and witness a fox transfixed in the headlights. The shots of sledding children and their families in January, accompanied by one of Schubert’s Lieder, recall images from 16th-century Dutch landscape painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

We see the beekeeper in the park securing his hives for the winter and the colors returning in the spring, the bees returning to life and the people returning to the park, while nothing seems to change in the hangar. Even after Ibrahim moves out into his own apartment after a year in the refugee shelter, we see the same images of refugees arriving as we already know from the first scenes of the film.[14]

Scenes of life in the hangar comprise the film’s third formal level. These scenes are often bound up with the depiction of the use of the airport’s infrastructure as a means to organizes the refugees’ lives. Aïnouz avoids intimate scenes or coming too close to the people in the hangars. The result of his distanced camera is that the environment, logistics, and administration take up more space. Again and again, we see how children, adults, and the elderly are subjected to health inspections; how they always walk the same paths between the living containers, which are equipped, for fire-safety reasons, with neither ceilings nor doors; how they are invited via intercom, again and again, to proceed to an adjacent hangar for vaccination. Here, the political dimension of the intertwining of infrastructure and architecture becomes visible through the new function that the infrastructure of the airport, with which we are all so familiar, takes on through its use as accommodation for refugees. “For,” Gabriele Schabacher summarizes this political dimension, “insofar as infrastructures like architectures actively divide, organize, limit or distribute space, and at the same time occupy it aesthetically and symbolically, they are genuinely connected to the question of power relations.”[15]

We see young men smoking in front of and behind the airport and talking to their families on the telephone. No less impressive are the repeated high-angle shots of the living containers in isometric perspective, which come to resemble rooms in a computer game. As one of the residents justifiably complains, private space is hardly possible. By nonetheless making an effort to respect that space, Aïnouz makes its absence all the more painful.

One scene shows Hussein conversing with friends. They sit outside smoking shisha with a view of Tempelhofer Feld and joke about their situation: “Man,” one says with a laugh, “where else do you find a view like this. The best outlook ever. I wish we had a car so we could drive around the park.”

The right of ownership, violence, and the critique of violence

The difference between the world of the refugees in the hangars and the world of Tempelhofer Feld is made palpable by the film. Those in the park use the erstwhile airfield’s idle infrastructure for recreation, athletic exercise, and varied modes of transport. By contrast, the infrastructure in the hangars is redeployed to administrate and organize the refugees. The violence inherent to this difference is revealed in the film on both an aesthetic and sensuous level. Despite their immediate proximity, the two worlds have neither contact nor overlap. It becomes obvious how different the right to take one’s place in the world is for those who are forced to flee their homeland and for those members of the civil society who are able to use legal means to appropriate Tempelhofer Feld.

The film offers neither solution nor political prescription. Its radicality lies in raising questions. One comes to reflect that the 100% Tempelhof Initiative, whose goal was to prevent the market capitalization of the grounds by transforming them into a recreational area for public use was in no sense a critique of the primacy of the right of ownership. What felt like a revolution was not one, as a look at Kant’s philosophy of law shows. The decision to define a site as common property is entirely within the framework of the bourgeois constitution founded on the right to property.

Kant anticipated the situation of a land being declared “free, that is, open to everyone’s use” within the bourgeois legal system based on the primacy of the right of ownership. He emphasized that this in no way implies that the land is originally free or, as he writes, “rejects possession of its own accord.” Instead, it first becomes free by means of a contract and is therefore “actually in the possession of those people (taken collectively) […] who reciprocally refrained from or suspended its use.”[16] What the film reveals by contrasting life in the hangar with life on Tempelhofer Feld is the persistence and acceptance of that violence. Along the same lines as Kant, it suggests that this violence is at the heart of any community based on the primacy of ownership. As Kant’s “Metaphysical First Principles of the Doctrine of Right” makes clear, such violence and its place in any societal order founded on the right of ownership is in no way hidden, but is designated and precisely named as such. A critical engagement with Kant’s text will therefore make it possible to determine whether a critique of this violence—a violence inscribed in the very history of its infrastructure—is possible, and what its starting point might be.

Where does this violence appear and what systematic place does it assume? Kant explains that violence [Gewalt] (potestas, violentia)—in distinction from power [Macht] in the sense of potentia[17]— appears wherever the a priori idea of an “original community of the land” crosses over into the a posteriori (and hence historically concrete) external distinction between ‘yours’ and ‘mine.’ This process is historical, which for Kant implies that it is mediated by human finitude. For Kant, the human is simultaneously a rational and a natural being. To the extent that we are rational, we can freely determine ourselves and our lives; to the extent that we are natural, we are subject to the laws of nature, that is, we can die, become sick, and deceive ourselves, but above all we are subject to our passions. Both human finitude and the limits of human capacity [Unmündigkeit] stem from this natural side. The division between a realm of nature and a realm of reason goes not only through the determination of humankind, but runs through the entire philosophy of Kant and determines the thinking of humankind and our order of knowledge until today. It is bridged in Kant’s doctrine of law by means of violence. Physical violence is constitutive for the first historical taking possession of the land—a taking possession that is indeed “primordial” [anfänglich], but likewise “original” [ursprünglich] on account of its systematic significance. This can be seen in the way that Kant describes the original, historically first taking possession of land in terms of “domination” (occupatio)[18]. It occurs by means of physical violence and leads to an unequal distribution of the land. As Kant states, the land cannot of its own accord reject possession. But it can answer the question as to how far the authority of its would-be possessor extends: “If you can’t protect me then you can’t command me either.”[19]

For Kant, this violence is neither unjust nor illegitimate, even when it precedes any civil contract. Rather, it is retroactively legitimated by virtue of its civil-legal function as ‘publicly lawmaking violence.’ But here again one must keep in mind that the justness—the necessity even—of all violence accompanying the original acquisition of land lies in the a priori idea of the “original community of the land.” Violent taking possession is for this reason legitimate, even before the inauguration of civil law, since it presupposes the original community that respects the possibility of possession.

Kant defines possession as the “legally mine […] with which I am so connected that the use that another would like to make of it without my consent, would damage me.”[20] This definition indicates a further reason why the right of ownership takes on central importance for Kant. It suggests that “mine” and “yours” assume a meaning beyond the body’s borders that is both generally intelligible and generally respected; that an apple belonging to me is seen as a part of me, even if it just so happens to be closer to someone else. For Kant, a contract is necessary for this seemingly metaphysical expansion of the human’s borders beyond the corporeal. But a contract presupposes, if it is legitimate, compliance with the categorical imperative, or the maxim according to which “my action, or even my state of being, can coincide with the freedom of everybody according to a universal law.”[21]

We can now see that Kant’s right of ownership is connected with the universal applicability of human rights. A “legal person” [rechtliche Person] is, for Kant, characterized by one’s assertation, “in relation to others, of one’s value as the value of a person.” According to Kant, law [Recht] is grounded in the obligation that is explained “from the right of humanity in our own person.”[22] By way of this connection between law and human rights, it becomes clear that Kant connects justice to right in the following definition: “That which is right according to external laws is called just (iustum), that which is not is unjust (iniustum).”[23]

This connection between law and human rights also explains the difficulty of mounting a critique of the violence that leads to the enduring and unequal distribution of ownership in the sense of the right to use things. For such a critique will always invoke the danger of putting into question the existence of the law of reason [Vernunftrecht] and the respect for human rights that proceeds from it. From what point might such a critique start out?

A possible critique of violence

For a possible answer to this question, I would like to turn to the conclusion of Peter Fenves’s reading of Kant’s “Metaphysical First Principles of the Doctrine of Right” and Walter Benjamin’s short “Notes Toward a Work on the Category of Justice.”[24] Benjamin’s notes were written in 1916 and preserved in the diary of his somewhat younger friend, Gershom Scholem, then nineteen years old. They constitute the beginning of Benjamin’s long-standing engagement with the relation of politics, right, justice, myth, and violence, which culminated in the frequently discussed 1922 essay “Toward a Critique of Violence.” As Peter Fenves precisely and convincingly demonstrates, Benjamin’s notes accomplish, despite their shortness, a systematic contribution to the project of a critique of violence, insofar as they formulate the fourth critique never written by Kant.[25] Benjamin’s notes begin with the distinction between human rights and the (nonexistent) rights of things. For Kant, a thing is distinguished by the fact that it, unlike a person, can be used and possessed and, by virtue of this possession-character, contribute to the law of reason [Vernunftrecht] and the safeguarding of justice. By contrast, Benjamin’s notes begin with the following:

“To every good, limited as it is in the temporal and spatial order, there accrues a possession-character as an expression of its transience. But the possession, caught as it is in the same transience, is always unjust. Therefore, no order of possession, however it may be articulated, leads to justice.”[26]

In opposition to Kant, for whom justice is connected to the law of reason [Vernunftrecht] and thus to the possession-character of things, Benjamin asserts that the condition of justice is a “good” “that cannot be a possession.” He further specifies that this good, which cannot be a possession, must be a good (Gut) through which goods (Güter) become dispossessed. Benjamin begins his critique with Kant’s maxim, according to which the land, against the background of an “idea of the original common ownership of the land,” is distinguished by its possession-character as a thing that must be taken possession of so that people can constitute and respect themselves as an historical community of possessors. In other words, Benjamin begins his critique of violence with Kant’s definition of the world as a thing, distinguished by its possession-character and lack of accountability [Zurechnungsfähigkeit]. Kant refers here to Aristotle’s Metaphysics, which conceives of substance in terms of passive material. If Benjamin refers to justice not as distributive justice, but as a “state of the world” in which the world is no longer defined by its possession-character, then his critique of violence simultaneously implies a critique of the metaphysical position that implicitly subtends the “Metaphysical First Principles of the Doctrine of Right.” That the same Aristotelian metaphysics provides the basis for the Marxist critique of private ownership of the means of production is made clear by Benjamin’s interesting note on socialistic and communistic theories of the relation between possession and use:

“Every socialist or communist theory misses its goal for the following reason: because the claim of the individual extends to every good. If individual A has a need z that can be satisfied with good x, and one therefore believes that good y, which is like x, may and should be given, for the purpose of justice, to individual B in order to assuage the same need, then one errs. For there is the entirely abstract claim of the subject, in principle, to every good—a claim that in no way refers back to needs but, rather, refers to justice, the ultimate direction of which probably does not tend toward a possession-right of the person but, rather, toward a good-right of the good.”[27]

It is of central importance for any critique of the violence inscribed in and promoting infrastructure that the critique of the metaphysics subtending the Kantian, liberal, and Marxist theories of violence alike be related to the concept of the individual and the relation of body and sexuality. It is well known that Kant’s division of the human into a rational and a natural being leads, as already mentioned above, to the definition of marriage as a contract regulating the reciprocal use of the sexual organs. Benjamin’s critique of violence is demonstrated not least with respect to this concept of love, sexuality, and the relation of right to the body.

In this way, Benjamin approaches the concerns of those representatives of queer theory who include in their critique of identity politics the critique of liberalism and the critique of the subject that distinguishes itself by the control it exerts over itself and over the world.

Aïnouz ends his film with the image of Ibrahim Al Hussein, who has returned from his apartment to visit Tempelhofer Feld. He thinks of his family, asking himself whether he will ever see them again. We then witness a sky sliced through by the condensation trails left by planes flying over Berlin. Again, an affection image, which makes you wonder. It raises the question whether the mobility promised by flying could ever heal his longing, and thus the question concerning the relationship between displacement and mobility and the related issues: does the world fall, can it even fall under the categories of property or ownership? What does it mean that there is a universal right of people to a place in the world? How would a world look like that followed Benjamin’s insight that possession is always unjust?

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter (1995[1916]): „Notizen zu einer Arbeit über die Kategorie der Gerechtigkeit.“ Frankfurter Adorno Blätter IV, herausgegeben von Rolf Tiedemann, München: edition text + kritik, 41–51.

Bittencourt, Ela (2018): „Reinventing Space: An Interview with Karim Aïnouz”, in: Mubi.com, 6. Mai 2018, (09.09.2022).

Deleuze, Gilles (1996): Das Bewegungs-Bild: Kino 1. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Deleuze, Gilles/Guattari, Félix (2005): Qu’est-ce que la philosophie?, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

Deuber-Mankowsky, Astrid (2020): „Affektpolitische Arbeit am Dokument am Beispiel von Yael Bartana und Sharon Hayes“, in: Balke, Friedrich/Fahle, Oliver/Urban, Annette (Hg.): Durchbrochene Ordnungen. Das Dokumentarische der Gegenwart. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, S. 153-170.

Fenves, Peter (2010): „7. The Political Counterpart to Pure Practical Reason: From Kant’s Doctrine of Right to Benjamin’s Category of Justice”, in ders.: The Messianic Reduction: Walter Benjamin and the Shape of Time, Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2010, S. 187-226.

Kant, Immanuel (1968): Metaphysik der Sitten, in: Werkausgabe Band VIII: Die Metaphysik der Sitten, Hg. von Wilhelm Weischedel. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Loick, Daniel (2016): Der Missbrauch des Eigentums. Berlin: August Verlag.

Schabacher, Gabriele: “Unsichtbare Stadt. Zur Medialität urbaner Architekturen“, in: Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft 12/2015, 79-90.

Taylor, Meredith (2014): „Cathedrals of Culture (2013)”, in: Filmuforia: The Voice of Indie Cinema 10/2014 (20.04.2023).

[1] Cf. Deuber-Mankowsky (2017)

[2] Deleuze/Guattari (2005) 155. All translations by RS unless otherwise indicated.

[3] Kant (1968)

[4] Kant (1968) AB 64,65.

[5] Translator’s note: I have translated Eigentum as “property” or “ownership,” depending on the context, and Besitz as “possession.” Wherever possible I have translated “Recht” as right, even where “law” is more colloquial, with all exceptions indicated by the German in square brackets. Following Edmund Jephcott, I have translated Gewalt, whose range of meaning encompasses “violence,” “force,” and “power”, as “violence” throughout, although these other meanings should also be held in mind.

[6] Taylor (2013)

[7] Kant (1968), AA06

[8] The conversation took place on January 4, 2019, in Berlin. Cf. Ela Bittencourt: “Reinventing Space: An Interview with Karim Aïnouz.”

[9] Kant (1968), AB 64, 65.

[10] Ibid., AB 85, 85.

[11] Deleuze (1996), 136.

[12] Kant (1968), AB 84, 85.

[13] Deleuze (1996),125.

[14] Translator’s note: Central Airport THF may no longer be a refugee shelter, but the displacement documented in Aïnouz’s film has not ceased. In light of the war in Ukraine (this translation was done in spring 2022), it bears mentioning that one of the “new” refugees featured in the film was already fleeing from Donetsk, one of the centers of current fighting.

[15] Schabacher (2015), 88.

[16] Kant (1968), AB 64, 65.

[17] Ibid., AB 57, 58.

[18] Ibid., AB 83.

[19] Ibid., AB 88.

[20] Ibid.,AB 55. In his essay “Der Missbrauch des Eigentums” (2016), Daniel Loick has shown how closely the relationship between use and property is linked in the liberal theories of property, such as Locke’s and even in Hegel’s ontological justification of property. For Hegel, too, property and possession are tied to the will and therefore constitutive of becoming a subject. For Hegel, too, the possibility of property is necessary for every subject, but its distribution is a legal contingency and beyond criticism.

[21] Kant (1968), AB 33, 34.

[22] Ibid., AB 43, 44.

[23] Ibid., AB 23, 24.

[24] Cf. Fenves (2010): 187-197.

[25] Ibid., 198.

[26]Benjamin (1995 [1916]), 41.

[27] Ibid.