Attack of the Cyberzombies: Media, Reconstruction, and the Future of Germany’s Architectural Past

TRANSIT vol. 10, no. 2

Rob McFarland

Abstract

While in Frankfurt a few weeks ago, I visited the site of the Dom/Römer project, a series of 35 buildings that are under construction in the historical center of Frankfurt am Main. While most of the buildings are going to be modern interpretations of the houses that once stood on the small parcels in Frankfurt’s city center, fifteen of the buildings will be historical reconstructions of historical buildings. As I approached the building site, I walked along a fence that had been covered with a vinyl picture of an artist’s rendition of the finished project. Scrawled across the picture was a graffito: “Bitte richtig alt. Kein Zombie!” The term “zombie” has been a battle cry for anti-reconstructionists from all over Germany as they watch historical reconstruction projects fill the empty spaces in their destroyed historical city centers. In this paper, I will investigate the current discourse that has conflated architecture with necromancy in German city planning. Are these reconstructions the signs of a crisis in Modernism, a sweeping wave of uncritical nostalgia, or dangerous returns to evil ideologies of the past? Using Walter Benjamin’s Kunstwerk essay, I will explore the role of historical reconstruction as medial architecture, buildings that function more like film than the so-called “authentic” architecture that is preferred by the current generation of Denkmalpfleger. What happens when a destroyed Bauwerk reaches the age of its technological reproducibility? These “zombie” buildings, I will argue, reveal mythical underpinnings in the projects of Modernism and the religious practices inherent in the concept of authenticity historical monuments.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to my generous mentor Prof. X, who once unknowingly leaned on a surviving stone fragment of Berlin’s Stadtschloss while I was talking with him in a library in Berlin.

Go to any blockbuster film this season, and you are sure to see some city in peril. Supervillains seem to prefer urban settings for their conquests, at least that is where the superheroes always seem to meet them for a final battle. As the ultimate public space, cities serve as the place where we ritually overcome aliens, comets, volcanoes, earthquakes, and many other real or imagined threats to civilization as we know it. And, as the films 28 Days Later, I am Legend, World War Z and countless video games have made clear, there is no place like a city for a zombie invasion, driven by whatever biohazard thrives on high concentrations of humans. Like the superheroes in the megaplex cinemas, contemporary architects have eagerly attacked the latest hypothetical challenge to the carefully engineered urban environment. Since 2010, the “Zombie Safe House Competition” has invited architects to design buildings that keep urban inhabitants safe from lurching, brain-hungry zombies intent on driving humanity to extinction (“N.A.”). Good design is more than a silver bullet: we can avoid monsters and destruction altogether if we put our trust in well-conceived architecture.

Architects and architectural critics not only keep us safe from biohazards, but also from other species of walking dead that might arise in the urban landscape. In his 2013 article in Der Spiegel titled “S.P.O.N.—Der Kritiker: Aufstand der Zombies,” Georg Diez warns that zombies are in the process of taking over Berlin. There is no architectural protection from these zombies, however: the zombies themselves are architectural phenomena:

Es ist ein wahrer Zombieaufstand, den Berlin da gerade erlebt. Untote Ideen kommen ans Licht, ewige Wiedergänger wie die leidige Traufhöhe, das sogenannte Ensemble, all die Kampfworte aus dem Kalten Krieg des Bauens, der ausgetragen wurde, nachdem die Mauer gefallen war und doch die Demokratie mal hätte gefragt werden können, was ihre Form ist, was ihre Schönheit ist, was sie will und verlangt, Offenheit vielleicht und Orte für alle und eine echte Bürgerlichkeit.

Undead concepts such as “ensemble” and “uniform building height” are again rising from the ground in Berlin. And it is not just concepts that are returning from the dead, but entire historical buildings are rising out of the buried foundations of the past. In a 2014 post on the London Review of Books blog, critic Glen Newey looked at Berlin’s plans to rebuild its city palace and sent out a grave alarm that “Berlin’s Zombie Dawn” was upon us (Newey). Indeed, the world has watched the rise of the long-dead palace by means of webcams placed on surrounding buildings. First, the skeletal historical foundations were unearthed and studied, then the site was prepared, and finally the rising new shape of the Berlin City Palace, now called the Humboldtforum, rose to obscure the cathedral behind it, like a revenant feasting on the bodies of the living architecture around it.

The rising historical buildings are not ruined corpses, but reinforced, technologically enhanced versions of their historical selves, more cyber-zombies than your garden-variety lurching, rotted revenants. These technical monstrosities, at least as far as Georg Diez is concerned, are poised to destroy the ideal “Offenheit” and “echte Bürgerlichkeit” of the modern German city. Diez’ view of the reconstructed zombies is calm compared to those of architectural critic Christian Welsbacher, who calls the modern German city “das wilde Rekonstruktistan” full of “Kannibalen” who eat their own relatives in order to assimilate the “Kräfte der Vergangenheit” (12, 14).

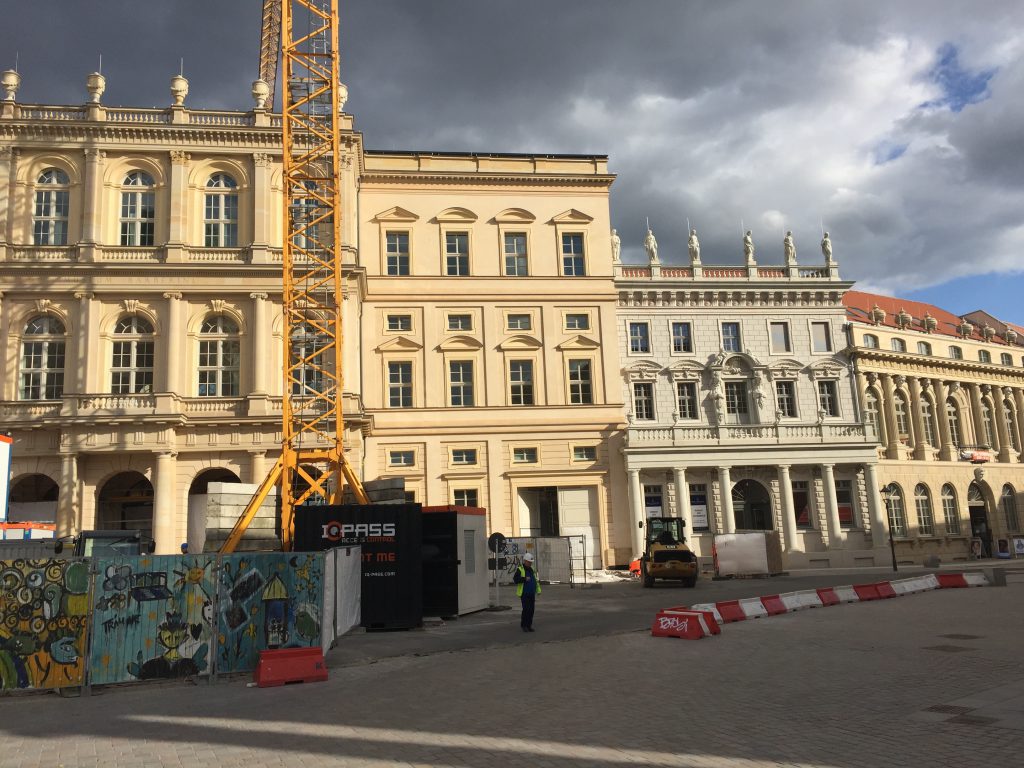

As a part of a religious and cultural tradition that has traditionally included the concept of the resurrection from the dead, why are German historical reconstructions cast as monstrous, as zombies rather than as other more benign resurrected beings? Perhaps the sheer number of reconstructions is fueling the backlash among architectural critics who decry the doom of post-Wende Germany and its cities. The Berlin City Palace/Humboldtforum project is currently the most high-profile historical reconstruction site in Germany, but other reconstruction projects are capturing headlines in many different cities across that nation. The city of Potsdam has regained its own city palace, now the home of the Landtag assembly for the state of Brandenburg. Around the palace, reconstructions of three more baroque buildings have just been completed, including the so-called “Palais Barberini,” which will house a collection of East German art from the DDR period. Dresden’s Frauenkirche is possibly the most famous and influential German reconstruction. The completion of its cream-colored stone bell not only inspired the rise of a reconstructed Altstadt around it, but also created a profound shift in the arguments surrounding reconstructions everywhere. Webcams documented fascinating scenes of huge, uneven blocks of rubble being perfectly fitted into computer-generated and laser-straightened new church walls, and the ethical question of “dürfen” (are we allowed to rebuild?) turned into a technological discussion of “können” (are we capable of rebuilding?) (McFarland and Guthrie 227-229).

And the phenomenon of historical reconstruction is not limited to the urban centers of the former East Germany: Frankfurt am Main has torn down its modern “Technologisches Rathaus” and is in the process of restoring the “Dom/Römer” quarter, including several reconstructions of historic buildings that line the newly-constructed contours of ancient streets and squares. The German urban landscape looks older now than it did a few decades ago, as long-lost historical buildings rise from the dead, returning as if they had never been gone.

Another reason that architectural critics have responded with such vehemence against historical reconstruction has to do with some of the core doctrines of Modernism. In his architectural history entitled Todsünden gegen die Architektur, Herbert Weisskamp explores the Calvinistic impulses that drove early Modernists such as Adolf Loos, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Turning Modernist rationality against itself, he shows how architectural doctrines have come to inhabit a blurred space between Humanist ethics and religious morality (13-29). In the decades since the fall of the Berlin Wall, one particularly religiously-laden architectural doctrine has received a lot of playtime in the discussion of the reconstructions in Germany: the commandment that architecture shall be “ehrlich,” or honest, or, to use an equally fraught but less religiously-loaded term, authentic. Because reconstructions are by definition not authentic, contemporary architectural critics see them not only as morally dishonest, but counterproductive. A modern copy of a building, Thomas Will explains, does not serve to represent the urban historical process. Instead, the reproduction actually obscures history:

Auf der anderen Ebene ist nach der Autorität von Bauten als Geschichtszeugen zu fragen. Hier kann es im Gegensatz zur ästhetischen Ebene keine Annäherung durch Abbildungen geben. Im Gegenteil: Wo die Imitate dem historischen Vorbild allzu ähnlich werden, wirkt der Hinweis auf “die” Geschichte gerade verfehlt, denn diese verschleiern sie gerade. (31)

The more successful the copy, Will argues, the more useless it becomes to the city’s interaction with history. The manifesto of the initiative to stop the reconstruction of the Berliner Stadtschloss, titled “Kein Schloss in meinem Namen,” also criticizes the planned reproduction as a “Vergessensmaschine” and an “Idealbaukörper […], der alle Verwerfungen und Wandel deutscher Geschichte verdrängt und nach der erneuten Tabula-Rasa die Fiktion einer intakten Tradition zur Schau stellt” (“Kein Schloss”). Will agrees with the idea that reconstructions are devoid of the attributes of a true architectural monument (Baudenkmal), and will represent “libertine” ideals:

Die geschichtliche Autorität, die sich im überlieferten Werk, besonders im Baudenkmal ausdrückt, versperrt sich jedenfalls jedem Versuch der Übernahme in künstliche Abbilder. Spätestens hier müssen die Illusionen zerbrechen, die aus der libertineren Vorstellung erwachsen können, dass heute alles möglich sei.” (31)

According to Will, a Baudenkmal possesses historical authority because of its authenticity. No copy—no matter how technically perfect—can reproduce this authority. In fact, several critics of reconstruction claim that such projects erode the authenticity of “authentic” buildings. Reinhard Seiß reports that historians are worried about the effect that the reproductions might have upon Germany’s surviving historical architecture: “Wenn man sich die Freiheit nehme, herausragende Werke der Geschichte nach Belieben zu wiederholen, entwerte man alle authentischen Baudenkmäler.” Peter Kulka sees an even darker future: reconstructions will not only undermine the authority of Germany’s built history, but they will serve as the beginning of an ongoing assault on the authenticity of all architecture: “Seine Bauten haben mit den historischen Gebäuden und ihren einstigen Funktionen nur wenig gemein. […] Was ist noch echt in Deutschland? In einigen Jahren wird man nicht mehr differenzieren können, was authentisch ist und was nachgebaut” (Kulka). Continuing Kulka’s pessimistic train of thought, Will maintains that because reconstructions are devoid of the authority of authentic edifices, they are not only deceitful, but potentially harmful to the “Rest der Aura” that remains in truly historical architecture (Will 31). As he uses the term “Aura,” Will tips the careful reader off to the mythical underpinnings of the idea of authenticity in architecture.

In their decrying of the immorality and monstrosity of historical reconstructions such as Dresden’s, the Berlin Stadtschloss and Frankfurt’s new/old Dom/Römer quarter and calling these projects “lies” and “artificial replicas,” critics have perpetuated an outmoded tradition in art criticism that places authenticity as one of the most important attributes of great art. In his canonical essay “Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit,” the early twentieth-century cultural critic Walter Benjamin investigates the relationship between an “authentic” work of art and a technically-produced reproduction of the same work. Going back to the earliest works of human art, Benjamin illustrates how the aura of artworks is embedded in the ritual practices of magic and religion. The authenticity of art is integral to its status as a cult object. Thus, when art historians speak of their “pilgrimages” to Dresden’s Galerie Alte Meister to stand before the very copy of the Sistine Madonna painted by the hand of Raphael himself, they are revealing the role of the museum as the heir of the church. Benjamin speaks of a watershed moment in the history of art when the ability to make and multiply copies of art reached a level of technical sophistication that affected the privileged position of an authentic work of art. With the advent of photography and especially with the development of film, copies became more than imitations. Like any good Freudian doppelgänger, reproductions can turn maliciously upon their original works of art, bringing elements of the original to light (by means of enlargement, slow-motion, etc.) that would have been previously unattainable (Benjamin, “Das Kunstwerk” 476). Benjamin imagines the positive force of technological reproduction as it works toward its destructive, cathartic goal, “die Liquidierung des Traditionswertes am Kulturerbe” (478).

Although his “Kunstwerk” essay is best known for its extensive discussion of film, Benjamin also gives a privileged position to architecture. The power of the masses vis-à-vis art has always been present in architecture, as opposed to other artistic media. In the final section of his essay, he explains how the very nature of human interaction with art changes when the interaction becomes a mass phenomenon. The mystical power no longer belongs to the work of art: whereas a painting or sculpture previously engulfed the individual viewer, the masses—now themselves unleashing their own mythic power—drown the work of art themselves. Because humans have an inherent, habitual, tactile relationship to the buildings that shelter them all of their lives, architecture cannot easily lull them into the kind of mystical state of contemplation brought about by a purely optical artwork:

Die Architektur bot von jeher den Prototyp eines Kunstwerks, dessen Rezeption in der Zerstreuung und durch das Kollektivum erfolgt […] Bauten werden auf doppelte Art rezipiert: durch Gebrauch und durch Wahrnehmung. Oder besser gesagt: taktil und optisch. (504)

Although architecture can also be experienced optically, humans have to work against their own nature to turn their scattered, unfocused vision (Zerstreuung) into the kind of focused “attention” (Aufmerken) needed to truly lose oneself in a work of art. Even though he connects this scattered mass vision to film, he qualifies his statement: “Ursprünglicher ist sie in der Architektur zuhause” (466).

If a technically perfect reproduction of a work of art reduces the cult value (Kultwert) of the original, then the technically perfect reproduction of a building could potentially have the same effect on the cultural practices that cast a work of architecture into its assumed mystical role as an authentic temple of history. What could these potential functions be for a reconstructed church, palace, or city center? Liberally appropriating Benjamin’s argument, one could see architectural copies as having the potential to counteract the unconscious use of mythology in the political and aesthetic discourse of historical construction. More than mere “forgetting machines,” historical reconstructions undermine the very idea that buildings can or should have a metaphysical connection to an idealized time, place, or person. As discussed earlier, critics of historical reconstructions see the projects as destructive to every authentic architectural monument across Germany. The reconstructed Frauenkirche, for example, has not been designated as a monument (Denkmal), for it does not fulfill the traditional definition of such a structure (Marek 135). Instead of existing as a concrete location of history, the reconstructed building becomes a part of a more ephemeral kind of building that Katja Marek calls “Medienarchitektur” (157). This media-driven architecture, as Marek explains it, exists first as pictures of the destroyed building, architectural renderings of the reproduction, and digitally manipulated images showing the virtual building inserted into the context of the real cityscape. These initial images are mass-consumed on the internet, in newspapers, on television, and on large advertising billboards, allowing them to be effectively publicized and marketed to the public (Marek 157). After the media images successfully sway public opinion in favor of the reconstruction project, more images are proliferated during construction (on webcams, for example, or at the traditional German Richtfest, or topping-out ceremony). The image of the completed building then becomes further proliferated as a part of advertising campaigns, tourist brochures, etc. The resulting edifice “ist das Ergebnis verschiedener Medien, sie ist eine Architektur, die aus Medien entstand und kann damit in diesem Wortsinn als mediale Rekonstruktionsarchitektur bezeichnet werden” (Marek 158). While a so-called “authentic” building officially recognized as a Baudenkmal certainly has its own media-driven presence as a visually recognizable icon and a tourist attraction, it also represents the kind of historical aura that transcends the indignity of advertising and tourism. Reproductions, on the other hand, are conceived, funded, and created in and through the media, and even in their built reality they maintain something of a transitory nature. Because, as Benjamin states, the copy slowly eats away at the focused, optical Kultwert of the work of art and replaces it with a new, distracted, tactile Ausstellungswert, the copy is bound to earn the scorn of those who want to defend the aura of the original work. Critics of reconstruction derisively point to the fact that these projects are conceived, financed, and built for the express purpose of attracting masses of tourists and then making money by feeding and housing them. Reinhard Seiß derides the vulgarity of this inferior purpose:

Neben aller Nostalgie sprachen auch massive wirtschaftliche Gründe für den Weg der Stadtreparatur. Schon als Baustelle war die Frauenkirche ein hervorragender Werbeträger für Dresden im Internationalen Stadtmarketing gewesen. …selbst in den USA wurde für den Wiederaufbau gesammelt, japanische Fernsehteams berichteten regelmäßig über den Baufortschritt.

The duties of an “authentic” building as a Baudenkmal, as an accurate, solemn witness of historical truth, are replaced by the media circus of the reproduction. Craven publicity campaigns attract—gasp—the Americans and the Japanese, who (characteristically, to assume from Seiß’ choice of nations) downgrade the true, local identity of Dresden into a tourist trap.

Beyond their ephemeral existence as Medienarchitektur, Germany’s historically reconstructed buildings function in a filmic way that resonates with Benjamin’s ideal of a reproducible work of art. With the often-repeated derision of reconstructed buildings as theatrical backdrops (Kulissen), critics bring attention to the connections between historical reconstructions and the medium of film. Andreas Ruby laments the status of Dresden as “eine Stadt im Kulissenwahn” (1). Ivan Reimann sees the façades of Dresden’s reconstructed Neumarkt as signs of a new “Diktatur der Ökonomie” where “nur das Jetzt, nur das Bild, die Oberfläche, eine photographierbare Kulisse zählen […]” (92). Peter Kulka sees the Neumarkt as a cinematic space: “Auf den Betonkuben dieser Gebäude werden historische Fassaden und Ornaments—wie auf Leinwände projiziert.” The most important filmic attribute of the reconstructions, however, is the distracted gaze that is brought about by the building’s permanent state of transience, so different from the mythical, eternal status of the ideal old city. Reimann identifies the façades of the Neumarkt’s hotels, the historicized restaurants, and the glass entryway to an underground garage as classic examples of what Marc Augé calls “Non-lieus,” the placeless spaces of modernity:

Orte des Flüchtigen, des Transits, der Durchreise, Orte, die nicht gelebt, sondern nur erlebt, nur gesehen werden, Orte, die im Vorbeigehen konsumiert werden[…]. Es ist eine Eigenart von Nicht-Orten, dass sie sich auf einem Postkartenbild, eine Reisebeschreibung, ein Werbespruch reduzieren lassen. Mehr noch: die Reduzierung eines Ort . . . auf ein Bild schafft eine merkwürdige Distanz zwischen der Stadt . . . und dem Reisenden, der sie besucht und der an einem Ort, so wie er wirklich ist, oder war, nie ankommen wird. (91)

Reconstructed buildings are useless as monuments, for they are not conducive to the kind of concentrated, time-intensive interaction that one might seek in a historically authentic space. Instead of being deeply erlebt (experienced), it is only superficially gesehen (seen). It is a place of distraction, of passing, in short—not a place at all. The traveller is perpetually separated from the reality of the place, and must stand outside and watch. In short, the viewer of a reconstructed building is the perfect modern viewing subject. Benjamin describes this modern interaction with space in his essay titled “Loggien” from his collection Berliner Kindheit um 1900. Standing in the courtyard of a building he knew as a child, he reflects upon the past, the present, and his own position as a viewer: “Seitdem ich Kind war, haben sich die Loggien weniger verändert als die anderen Räume. Doch nicht darum sind sie mir noch nah. Es ist vielmehr des Trostes wegen, der in ihrer Unbewohnbarkeit für den liegt, der nicht mehr recht zum Wohnen kommt” (296). Although time and space come together in this personally meaningful place, the courtyard and the balcony are both still uninhabitable for him, for they are places caught in a past from which he is hopelessly alienated. In other words, this uninhabitable place is a perfect habitation for the modern subject, and the perfect screen on which to cast the transient modern gaze.

A recent example of historical reconstructions in their proper function as non-places can be found in the Dresden author Ingo Schultze’s essay “Einem aus dem Ort Gefallenen.” Schultze gives a nostalgic look back on the ruins of the Frauenkirche. The first time Schultze sees the new Frauenkirche and the Neumarkt around it, he is startled and sickened at the way that the buildings serve as false backdrops devoid of any real history. First, he fixes his gaze upon the dark stones of the Frauenkirche, holding onto something that had actual historical meaning. But then his gaze “slides off” of the dark stones, onto the slippery surface of the creamy new sandstone. The inauthenticity of the buildings does not allow him to fix his gaze upon anything real or historical, thus detaching him from any sense of place:

Je näher ich der Frauenkirche kam, umso mehr schien sie sich zu verwandeln, um dann, vom Neumarkt aus betrachtet, zu ihrer eigenen Wachsfigur zu erstarren. Ich umrundete die Kirche, sah ins Coselsche Palais hinein, dem zwischen 1998 und 2000 entstandenen ersten “Leitbau” an der Frauenkirche. Wieder im Freien, sah ich nur Kulissen! Kulissen, die alte Häuser aus vergangenen Jahrhunderten vorstellen sollten…Hier fällt man aus der Zeit, und verliert somit auch den Ort. Was ist das für ein Geist, der aus Dresden ein Märchen machen will, und es damit der Geschichts- und Gesichtslosigkeit preisgibt?

In Schultze’s narrative, the reproduced Frauenkirche has lost its function as the heart of Dresden: it is a simulacrum of itself, as creepy and lifelike as a wax figure. He is repelled by the kitschy, colorful flatness of the images of the old buildings on the huge sheets of synthetic material that covers the scaffolding. But more horrifying than the images on the sheets are the real buildings— Kulissen, backdrops, stage sets, filmscreens upon which the past is projected for the fleeting, superficial consumption by crowds of tourists. In other words, the Neumarkt has become cinema. Just like a film, here is no original copy: It is a flat projection space for an ethereal veneer of history. It is created for consumption by a never-ending series of audiences that are looking for historical spectacle to divert and move them before they move on. For Schultze and others, entering the Neumarkt, this set of technical reproductions, the search for something real—like Schultze’s longing gaze at the authentic dark stones—will inevitably slide off onto the slick surface of the Kulissen. Mere tourists might swoon at the beauty of Baroque Dresden, but those serious thinkers in search of the city’s heart will search in vain.

The search for the authentic Baroque city is, of course, an oxymoronic errand. The neo-retro Baroque edifices at the heart of Berlin, Potsdam, or Dresden conjure up practices that were much more at home in the Baroque city than they are in our solemn, serious contemporary urban landscapes. Whereas being called kulissenhaft is the ultimate offense in an architecture based upon metaphorical ecclesiastical values such as “honesty,” the Baroque, as Thomas Kantschew reminds us, reveled in an

[…] äußerst verfeinerte[r] Unterhaltungslust und ein[em] raffiniert täuschende[n] (Masken-)spiel bis zu den ausgeklügelsten Wirkungen. Der fantastischen Mittel gab es reichlich: geistvolles Blendwerk, die Sinne betäubende Kulissen und grell-optische Effekte […]. Auch die neuen Bürohäuser und Hotels am Neumarkt werden für eine anspruchsvolle europäische (bzw. globale) Freizeitgesellschaft mit “Echtheit” und “Lüge” spielen. Aber wir Betrachter sind Teil dieses Spiels […]. Es ist ein Spiel in einer zunehmend ohnehin zwischen virtueller und realer Welt changierenden Zeit.

To fill the vacuum left by the rejection of postmodernism in German cities, it seems that the Baroque must rise from the dead to fulfill a need for embellishment and theatricality that modernism has tried so hard to eradicate.

For now, Germany is happy with a diet of a few Baroque reconstructions, those fascinating anachronisms that seem to outrage the pious modernists who for so long have thumped their copies of “Ornament and Crime” like a preacher at a revival. But, if technically-enhanced Baroque buildings can return to challenge modernity’s sacred birthright to authentic architecture, then the ghosts of ages past are now at the beck and call of German city planners. How long will it take before someone actually dares to reconstruct an ornament-laden Wilhelminian-era historicist building, that ultimate bugaboo that Modernism, with its minimalist manifestos, has repressed for over a century? Such a copy will be seen as madness, as hysteria, and as a provocation. The supposedly untenable position of such religiously-loaded dogmas of honesty, asceticism, truth, etc. will be faced with the most heretical sinner yet: a long-killed-off architectural freak-show raised from the dead by technology, a cyberzombie in a prom dress. The aura-worship of puritanical Modernism is still safe for now, but in film, and now in architecture, there can always be a sequel.

Works Cited

Augé, Marc. Non-Places. Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. Trans. John Howe. New York: Verso. 1995. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. “Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit.” Gesammelte Schriften: Abhandlungen. Vol. I: 2. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp. 1991. 471-508. Print.

————. “Loggien.” Berliner Kindheit um 1900. In Gesammelte Schriften: Kleine Proas. Baudelaire Übertragungen. Vol IV: 1. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp. 1991. 294-296. Print.

Diez, Georg. “S.P.O.N.- Der Kritiker: Aufstand der Zombies.” Der Spiegel 4 June 2013. Web. 5 Jan. 2012.

Historisch kontra Modern? Erfindung oder Rekonstruktion der historischen Stadt am Beispiel des Dresdner Neumarks. Ed. Ingrid Sonntag. Dresden: Sächsische Akademie der Künste, 2008. Print.

Kantschew, Thomas. “Vom Sehen, Schein und Sein.” Neumarkt-Dresden. Web. 5 Jan. 2016.

“Kein Schloss in meinem Namen.” Schlossdebatte 6 Dec. 2008. Web. 5 Jan. 2016.

Kulka, Peter. “Peter Kulka zum Thema Identität und Rekonstruktion.” http://www.brillux.de/service/fort-und-weiterbildung/architektenforum/rueckblick/dresden-2010/vortraege/identitaet-und-rekonstruktion/?L=0. Web. 24 May 2016.

Marek, Katja. Rekonstruktion und Kulturgesellschaft. Stadtbildreparatur in Dresden, Frankfurt am Main und Berlin als Ausdruck der zeitgenössischen Suche nach Identität. Diss. Universität Kassel. 2009. Print.

McFarland, Rob with Elizabeth Guthrie. “The Bauwerk in the Age of its Mechanical Reproducibility: Historical Reconstruction, Pious Modernism and Dresden’s Süße Krankheit.” Bloom and Bust: Urban Landscapes in the East since German Reunification. Ed. Gwyneth Cliver and Carrie Smith-Prei. New York: Berghahn. 2015. 227-229. Print.

“N.A.” “Zombie-proof architecture: When the dead start to walk, you’d better start building.” Economist 17 Aug. 2012. Web. 24 May 2016.

Reimann, Ivan. “Ein unlösbares Dilemma.” Historisch kontra Modern? 89-93. Print.

Ruby, Andreas. “Las Vegas an der Elbe.” ZeitOnline 9 Nov. 2000. Web. 24 May 2016.

Schultze, Ingo. “Ich war ein begeisterter Dresdner. Zum Auftakt der 800-Jahr Feier der sächsischen Hauptstadt—Nachtgedanken eines aus dem Ort gefallenen.” Süddeutsche Zeitung 31 Mar. 2006. Web. 5 Jan. 2016.

Seiß, Reinhard. “Vorwärts in die Vergangenheit.” Wiener Zeitung 28. Okt 2005. Web. n.p.

Weisskamp, Herbert. Todsünden gegen die Architektur. Düsseldorf: ECON Verlag. 1986. Print.

Welsbacher, Christian. Durchs wilde Rekonstruktistan. Über gebaute Geschichtsbilder. Berlin: Parthas. 2010. Print.

Will, Thomas (2008) “Städtebau als Dialog. Zur Wiederbebauung des Dresdner Neumarkts. Historisch kontra Modern? 28-33. Print.