“Biohaus”: The Bauhaus and the Biopolitics of Global Space

TRANSIT Vol. 13, No. 1

Aron Korozs

Abstract

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, art historians and urban studies scholars have been pleading for a more nuanced analysis of the Bauhaus in order to divorce from the one-sided affirmative reading of the iconic German art school. Yet, within the prevailing heroic narrative that still dominates contemporary public discourse after the 100-year anniversary of the school, the Bauhaus is praised for its affordable as well as working class-oriented design and it is thus depicted as intrinsically antithetical to today’s neoliberal housing market and bourgeois planning practices. To complicate this somewhat lopsided account, this paper draws on Henri Lefebvre’s critique of functionalist architecture and Michel Foucault’s notion of biopower to examine the late Bauhaus through a biopolitical lens. It first presents the Törten working-class housing estate in Dessau, Germany to scrutinize how biopolitical socio-spatial practices crystalize in Bauhaus urban planning and architecture. The second part of the paper turns to the film screen to discuss how the Weimar-era narrative of bio-functional modernism materializes in Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy’s late 20s, early 30s filmic works on urban life, the so-called “city symphonies.” Considering the postwar afterlives of the Bauhäusler, the Conclusion places these findings in a broader historical perspective and reflects on the contemporary implications of a Foucauldo-Lefebvrian rereading of the Bauhaus. It is within this final contextualization that the paper inquires into the possibilities of people-centered urban dwelling in the age of biopower.

I. Introduction

In 2019, countries throughout Europe marked the Bauhaus centennial with numerous events, exhibitions, and museum openings. The ephemeral German art school, which operated until its shutdown under Nazi pressure in 1933, trained over a hundred artists, architects and designers and is widely celebrated today for its protagonists’ efforts “to put art and architecture to use as social regeneration for the world’s working classes” (Saval). On the eve of its centennial, many contemporary journalists and public intellectuals contrasted the left-wing, “daring,” and even “obstreperous” attitude of the Bauhäusler with the conforming and market-oriented stance of present-day star architects and city planners (cf. Rauterberg, “Die Zukunft ist jetzt,” “Ins Zeitlose entrückt”; Berghausen). Within this contemporary heroic narrative, the Bauhaus appears as intrinsically antithetical to the current neoliberal housing market and elitist planning practices. At the official opening festival “100 Years Bauhaus”, German President Frank Walter Steinmeier embraced this account and echoed the message of the Bauhaus to the world, demanding “[t]he best possible life for as many people as possible” (Bundespräsidialamt 5). With its lingering and versatile influence on architecture and design, Steinmeier considers the movement “synonymous with modernity” (2).

But what kind of modernity? In the Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre highlights “the essential link between modern architecture and the project of capitalist modernization” (Stanek, Henri Lefebvre 148). He insists that the Bauhaus “despite the fact that its advent was hailed as a revolution – even as the anti-bourgeois revolution in architecture […] – […] expressed, formulated and met the architectural requirements of state capitalism” (Lefebvre 304). According to him, the Bauhaus, similar to other 20th century architecture schools and movements, fused “knowledge with power” in a way that ultimately fostered a top-down, unitary conception of building, production, and consumption. This, as Lefebvre puts it, “authoritarian and brutal spatial practice” (308) of the architectural avant-garde of the 1920s could be applied to utterly different politico-economic contexts. With standardized processes, underpinned by clearly articulated theories and ideologies, space at this point becomes what Lefebvre calls (125) “global space,” producible, interchangeable and governable on a larger scale than ever before, “waiting to be filled […]” (125) with the “worldwide, homogeneous and monotonous architecture of the state […]” (126).

In Michel Foucault’s oeuvre, space is a primary apparatus of biopower (Security 11), for the biopolitical control of the population could have not been achievable without the systematic management of bodies in space. Numerous scholars have scrutinized the materialization of biopower in modern towns and buildings based on this Foucauldian assumption (cf. Wallenstein; Stanek, “Biopolitics of Scale”). Yet the Bauhaus, in spite of its collectivist and technocratic spatial practice pointed out by Lefebvre, has received little scholarly attention in biopolitical studies.

In this paper, I argue that Lefebvre’s critique of the Bauhäusler’s “mastering [of] global space” (Lefebvre 125) confronts a similar dilemma of expert-driven population management as Foucault’s biopolitical thought. Putting the two theorists into conversation within the context of Weimar Germany, the paper unfolds the Bauhaus school’s role in the ever-expanding spatialization of biopower on two distinct albeit interrelated sites. It first presents the Törten working-class housing estate in Dessau, Germany to how biopolitical socio-spatial practices crystalize in Bauhaus urban planning and architecture. The second part of the analysis turns to film as a spatial mass medium as well as cultural artifact, displaying how bio-functionalist modernism materializes in Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy’s late 20s and early 30s filmic works on urban life. Subsequently leaving Weimar Germany behind and following Lefebvre’s concept of “global space,” the paper complicates these results in light of the transnational afterlife of the Bauhäusler. The conclusion briefly returns to the contemporary imaginary of “[t]he best possible life for as many people as possible” (Bundespräsidialamt 5) and addresses how Lefebvre’s vision of “differential space” (Lefebvre 381-383) as a conceptual antidote to homogenized “global space” offers an ethical potential for rethinking urban dwelling today.

II. Critique, Theory, Context

In The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre notes that “[t]he historian of space who is concerned with modernity may quite confidently affirm the historic role of the Bauhaus” (125). Although Lefebvre does not give a comprehensive account of the school’s history, his depiction of the institution and its founder, Walter Gropius, corresponds more closely to the period subsequent to the infamous functionalist reorientation of the Bauhaus in 1923.

The Staatliches Bauhaus was founded in 1919, in the immediate aftermath of the First World War and the subsequent November Revolution, which marked the end of the Hohenzollern monarchy and gave birth to the short-lived Weimar Republic (1919-1933). The complexity of the Weimar era crystalized into the school’s variegated weltanschauung, which – quite radically – shifted from an expressionist, neoromantic pedagogy focusing on individual artistic development to a rigid functionalist-technological approach (Colini, Eckardt 9; Forgács; Rennie Short). This was no unanimous decision, but rather a directorial response to the growing political and economic pressures of the time (Forgács 101). The 1923 Bauhaus exhibition under the new credo “Kunst und Technik – eine neue Einheit” (“Art and Technology – a new unity”) marked the start of a new era in Bauhaus history, in which technology became the ultimate leitmotif, and functionality, wide-range applicability as well as marketability started dominating the school’s agenda (Forgács 104-106; Rennie Short 143). This new functionalist model gave rise to the standardization and mass production of Bauhaus products and a top-down education and planning approach, which further evolved after the Bauhaus left Weimar for Dessau in 1925 (Koehler 20-21).

Lefebvre critiques Gropius’ post-1923 “Neue Einheit” program, which entailed the integration of artistic education in state-sponsored production (cf. Lefebvre 304). According to Lefebvre, the new techniques and controlled “planning procedures […] introduced by the architectural avant-gardes were essential for the development of capitalism,” facilitating “the unity of processes of production, distribution, and consumption in developed capitalism” (Stanek, Henri Lefebvre 148). As the primary tool of this modern “total project” of “global space” (Lefebvre 125), Lefebvre identifies the systematic fusion of living spaces and spaces of production. He accredits the Bauhaus with both the theoretical foundation and the subsequent spread of this practice (124). Under Gropius, this novel, albeit widely applicable spatial tradition of fusing dwelling and productive spaces becomes a “worldwide strategy” (105) of “bringing forms, functions and structures together in accordance with a unitary conception” (125).

Although Lefebvre was critical of Michel Foucault and his presumed “detachment from everyday life” (Harvey 429), Lukasz Stanek argues that “Foucault’s account of […] the biopolitical management of population as a whole pointed at a similar dynamic that Lefebvre addressed in his hypothesis of the […] homogenization of state-produced space” (Henri Lefebvre 154). In a similar vein, I propose that both Lefebvre’s argument about the authoritarian fusion of workplaces and dwelling-places within a trans-ideological “total project” of architecture as well as his thorough critique of state productivism echo Foucault’s thoughts on biopolitics: I argue that the Lefebvrian link between workplaces and dwelling-places hints at a biopolitical symbiosis between production and (spatialized) population, which Foucault laid out in his late lectures at the Collège de France.

In the final lecture of Society Must Be Defended (1975-1976), Foucault conceptualizes biopolitics as a “new technology of power” emerging in the early 18th century (243) which is concerned with the management and control of a given population as a whole, rather than with the disciplining of individual bodies. In The History of Sexuality, Foucault importantly links biopolitics with both capitalism (140-141) and the notion of modernity (143): Modern capitalism required the systematic management of productive bodies as well as the precise alignment of population-related phenomena with economic processes.

Throughout his subsequent lecture series, Security, Territory, Population (1977-1978), Foucault not only illuminates the economic motivation for the biopolitical shift, but also depicts its spatial consequences: The new town planning and building practices of the 18th century were meant to “modify and impose norms on living conditions” (367) and hence to surveil, manage and protect the productive population. We can find further hints of these spatialized biopolitical “fields of applications” (239) in Society Must Be Defended, where the “urban problem” (245) as a domain of biopower appears. Biopower is hence not only concerned with human beings as parts of a given population, but also with “their environment, the milieu in which they live” (245). Within the city and the milieu, Foucault sheds a critical light on working-class housing estates as sites of biopower (251), where a series of disciplinary and regulatory mechanisms (such as the location of the estate, its layout, hygienic rules, and welfare policies) target both the individual worker’s body and the working-class population as a whole.

Foucault’s examples of the biopolitical urban shift first and foremost deal with his native France. If we want to apply his analysis onto the German context, the Weimar Republic offers a rarely discussed example of biopolitical social as well as urban engineering (Dickinson 1). The biopolitical dimensions of the first Deutsche Republik have profound implications for the Dessau Bauhaus’ alignment with state economy, as pointed out by Lefebvre. Although Lefebvre does not explicitly mention the Weimar Republic in The Production of Space, several art historians argue that the history of the Bauhaus is deeply embedded in the context of Weimar Germany (Colini, Eckardt; Rennie Short; James-Chakraborty, Bauhaus Culture; —., “Beyond”). If we complicate these claims as well as Lefebvre’s account of Gropius’ statist reorientation with the biopolitical nature of Weimar’s welfare state, a Foucauldian rereading of the Bauhaus becomes inevitable.

Given the vast demographic, economic, and territorial losses of the First World War, public hygiene and public health gained new relevance in the welfare system of the young republic as well as in the panic-stricken and moralizing, bourgeois discourse of the time (Walter 342). Pathologizing urban life was a typical discursive element of Weimar intellectual life (320). Finding a “scientific” solution to “urban problems” (cf. Foucault, Society) and thus securing the necessary “biological foundations” (Walter 320) for post-war national resurgence was the ultimate goal of the German expert community of the time. The putative “phenomena of social and biological decay” included prostitution, vagrancy, child neglect and suicide, which – according to the scholars of the time – were “to be recognized as epidemies in modern, civilized states” (337).

In praxis, social hygiene (Sozialhygiene) emerged as the ultimate reactionary paradigm of the Weimar state. It constituted a normative interdisciplinary field (Gesamtdisziplin), which brought into focus every aspect of public and social life that could potentially affect the body. The discipline aimed at the greatest possible prevention against bodily harm as well as at the greatest possible protection of bodies in the largest possible (if not in the entire) population (Eckart, “Gesundheitspflege” 223-224). As Wolfgang Eckart highlights in his comprehensive study on Weimar public health (223), the practical social hygiene measures not only operated in the field of medicine, but also encroached upon other welfare policies concerning insurance, mother-child relation, work, and recreation as well as housing (226-229). Quite problematically, eugenics or racial hygiene also became an integral part of the social hygiene dogma of the time, with the objective of improving the alleged “biological substance of the German population” (Hau 120). This practice discloses the selective nature of biopower and the connection between biopolitics and racism that Foucault also points out in his work (Society 254).

In light of the ongoing housing crisis of the time, Weimar-era housing policies aligned the biopolitical social hygiene approach with the Lefebvrian dwelling–production symbiosis. While unproductive bodies, the so-called “asoziale Elemente” were denied public housing (Silverman 129), families of unemployed or part-time workers, the potentially useful workforce, were settled in state funded working-class housing “on the outskirts of major cities,” strategically located in sufficient proximity to local factories (131). The biopolitical motivation behind these measures is unmistakable: Edward Ross Dickinson argues that these policies were not born of pure philanthropy, but were carefully designed to “turn people into power, prosperity, and profit” (32). This is precisely how the biopolitical critique of the Bauhaus complicates the narrative of the school’s presumed objective of providing “[t]he best possible life for as many people as possible” (Bundespräsidialamt 5).

There is a clear tension between the normative imaginary of a best possible life and the practical motivation behind the advancement of living conditions in the era of biopolitics. Therefore, considering Lefevbre’s critique of the statist (re-)orientation of the Bauhaus and the rarely discussed biopolitical workings of the Weimar state, can we speak of a biopolitical shift in the history of the iconic German art school? To what extent did the late Bauhaus – as a supposedly “antifascist bulwark of democratic and/or socialist ideals” (James-Chakrabokry, “Beyond” 11) – follow the above-discussed Weimar-era biopolitical policies and socio-spatial practices? And to what extent did the Bauhaus discourse reflect the biopolitical as well as the pathologizing narratives of Weimar?

III. The Bauhaus Neighborhood: The Törten Working-class Housing Estate

Gropius’ Neue Einheit program marked a practical reorientation to functionalist education and design at the Bauhaus as well as a shift to architecture. Subsequent to the school’s move to Dessau, Gropius appointed Hannes Meyer as the head of the architecture department, whose functionalist-scientific approach greatly shaped the late Bauhaus (Forgács 159-181; Colini, Eckardt 9).

For Meyer, the architect’s atelier was “a scientific laboratory,” using rational observations and technological innovations to serve the collective good (Forgács 154). His curriculum thus relied on “scientific principles” (Colini, Eckardt 11) and “was primary concerned with housing in relation to its environment: the house in its symbiosis with the surroundings and various functions, from fruit trees through health issues to traffic” (Forgács 155). Under the now-famous slogan “Volksbedarf statt Luxusbedarf” (“The needs of the people instead of the need for luxury”), Meyer shared Gropius’ “minimum housing concept,” according to which the design process should only consider the biological needs of the dwellers (Colini, Eckardt 10-11). Meyer’s fascination with the biological functions and the environment of the dwellers may be best demonstrated in his twelve design principles:

1. sex life; 2. sleeping habits; 3. pets; 4. gardening; 5. personal hygiene; 6. weather protection; 7. hygiene in the home; 8. car maintenance; 9. cooking; 10. heating; 11. exposure to the sun 12. service; these are the only motives when building a house. We examine the daily routine of everyone who lives in the house and this gives us the functional diagram – the functional diagram and the economic program are the determining principles of the building project. (1928, as cited in Van Leeuwen, 71)

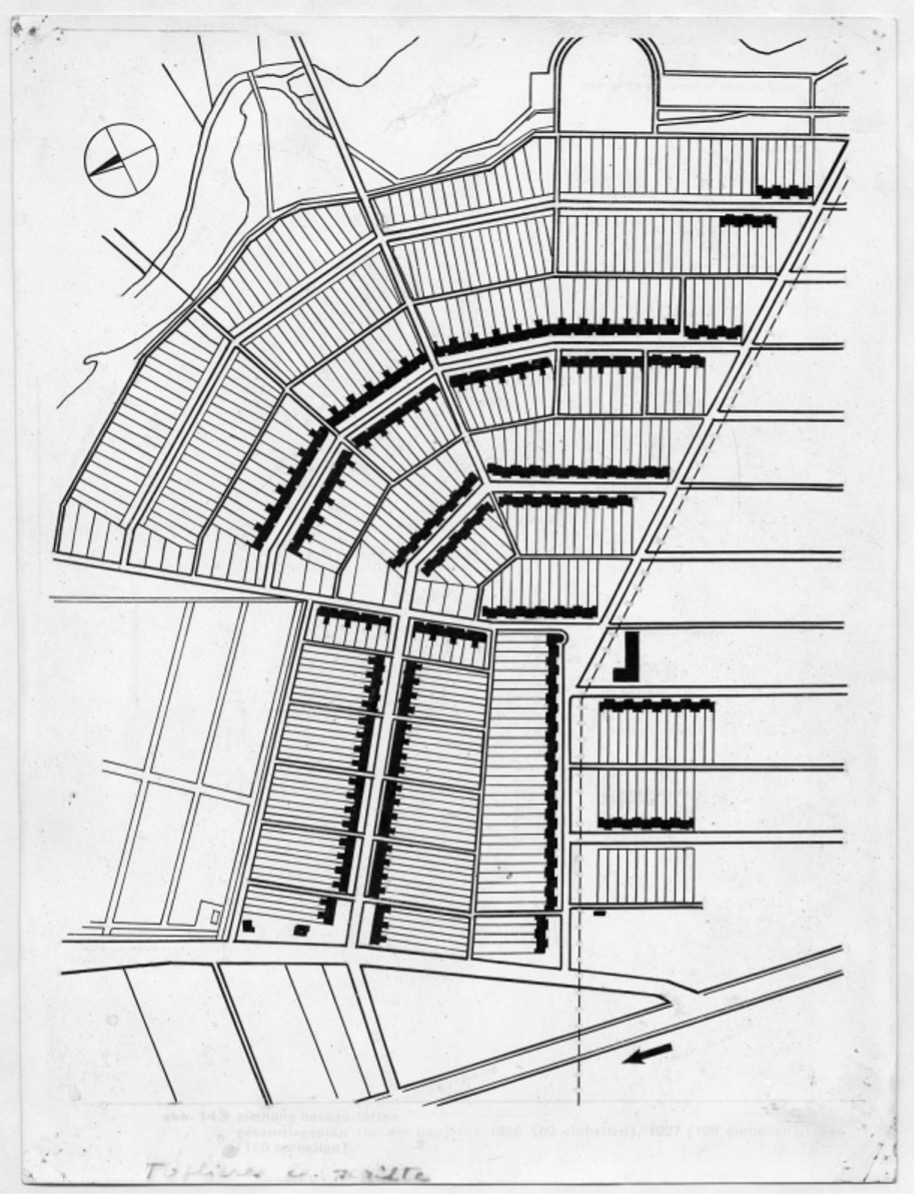

This Meyerian idea of scrutinizing the bodily aspects of dwelling (and aligning these with economic incentives) as a basis of architectural design reflects Foucault’s notion of biopower, which is concerned with both the population and the relations between bodies and their (built) environment (cf. Foucault, Society 245). In practice, Gropius and Meyer’s “biological concept” (Tomita) took shape in the Törten working-class housing estate (1926-1928), supported both by the city of Dessau and the local Junkers Aircraft and Motorworks, which “needed low-cost housing for its workers” (Forgács 153). The estate conformed with the Weimar-era housing paradigm of modern working-class neighborhoods on the outskirts of major cities but in proximity to production sites. Its 316 two-story “Volkswohnungen” (“people’s flats”) were complemented with gardens for food self-sufficiency and with direct access to the kitchen (Winkelmann 1-2). The aim of the design of the houses was to reduce production costs, which resulted in the exclusive focus on basic biological needs, primarily on sufficient space, ventilation, light, and hygiene (2). The construction was partly funded by the Reich Ministry of Labor and the Reichsforschungsgesellschaft für Wirtschaftlichkeit im Bau- und Wohnungswesen (Reich Society for Economic Efficiency in Building and Housing), which sought “to promote experimental housing research” (Isaacs 128). Thus, economic incentives such as providing housing for local workers and facilitating the research of cheap mass housing fell in line with clear-cut biopolitical calculations. Furthermore, Törten not only integrated production and dwelling within the planned housing estate: The housing blocks form a semi-circle around the so-called “Konsumgebäude” (“consumption building”), representing the “unity […] of production, distribution, and consumption” (Stanek, Henri Lefebvre 148), which Lefebvre later criticized (see figure 1).

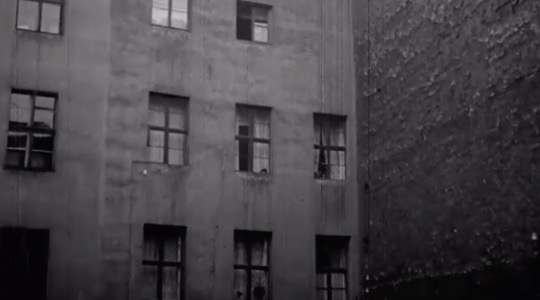

The 1928 documentary film, Wie wohnen wir gesund und wirtschaftlich? (“How to dwell healthily and economically?”) centers on the Törten housing estate and juxtaposes the Weimar “urban problem” with a functionalist urban future, which, as the title already suggests, ought to be cheap and healthy. The first part of the film employs the language of Weimar-era social hygiene, discussed earlier, and stages a dystopic housing crisis (“Wohnungsnot”) in big cities. The opening scene shows an aerial shot of Berlin’s crowded working-class neighborhoods and zooms in on their deteriorating condition (see figure 2). In the style of the avant-garde, the sequence provides a “collective spatial experience facilitated by” aerial photography, a novel technique which at the time “allowed the wide public to perceive the metropolis in its wholly new scale” (Stanek, Henri Lefebvre 150). Following the aerial shots, the title card reads that “[d]ark yards are true breeding grounds for vermin and disease, especially for children” (“Dunkle Höfe sind wahre Brutstätten für Ungeziefer und Krankheiten und besonders für Kinder verhängnisvoll”), introducing the motifs of public hygiene and child neglect with a number of pathologizing snapshots (see figures 3 and 4). According to Lefebvre, this modernist “pathology of space” and the image of “ailing neighborhoods” makes it possible for architects and planners to become the “doctors of space” and to “promote […] the idea that the modern city is a product not of the capitalist […] system but rather of some putative ‘sickness’ of society” (Lefebvre 99). Foucault calls this the “urban problem” (Foucault, Society 245) and describes it as a discursive instrument of biopolitical management. Subsequently, the intertitle suggests that the crowded housing conditions result in problematic activities such as “gossip, spat and strife” (“Klatsch, Zank und Hader”), reinforcing the image of the “unproductive” population as a collective burden for society. Shortly thereafter, inner-city neighborhoods are depicted as sites of “alcoholism, prostitution and crime” (“Trunksucht, Prostitution und Verbrechen”), a clear reference to the often-discussed asoziale Elemente of Weimar urban life (cf. Silverman, discussed above).

In the second part of the film, new neighborhood projects are presented as positive examples of modern dwelling. According to the intertitle, the large-scale garden city projects embody the shift from designing unique, single-unit houses to city planning. Oblique and abstract images show these new, organized and spacious settlements (see figure 5) – milieus in Foucauldian terms – evoking a strong contrast with the opening shots of Berlin’s narrow, crowded streets. In Wie wohnen wir gesund und wirtschaftlich?, Törten appears as the epitome of the modern housing project with its “extremely cheap” (“äußerst billig”) houses and its unique construction methods (“nach einem besonderen Bauverfahren hergestellt”). Minute-long scenes document the construction works in the style of 1920s industrial films (Goergen 111). The modern building elements and technological equipment on site are shot from different angles and appear both efficient and grandiose (see figure 6). The machines, especially the cranes, move in complete symbiosis with the working bodies.

Not only machines become symbolic elements in the film. Comparing the two parts of the documentary, darkness connotes disease. As the intertitle reads in the beginning: “If the sunlight does not come into your house, the doctor will” (“Wo die Sonne nicht hinkommt, kommt der Arzt hin”). The differences in living conditions between the inner city and the estate are hence both narratively and aesthetically underpinned with the absence of light in Berlin vis-à-vis the well-illuminated, close-to-nature Törten. The new housing estates fulfill the modernist requirement for the “illusory clarity of space” (Lefebvre 320) and thus seem legible and safe. While the Berliners are depicted as dark and besmirched by the dust of the city, well-dressed dwellers with a lighter complexion inhabit the houses in Dessau.

In the accompanying brochure Wie wohnen wir gesund und wirtschaftlich?, Richard Paulick addresses both architects and politicians in an impelling tone. Paulick pleads for “modern land, settlement, construction and housing policies, […] rational regional and city planning […] as well as rational construction techniques and dwelling culture” (as cited in Goergen 113). The film hence combines elements of economic modernization and social hygiene discourses to promote the functionalist practices of Gropius and Meyer. The final product is an industrial film with a “genre-typical pedagogical impetus” (118) as well as a filmic artifact that aesthetically demonstrates the various discursive influences shaping the post-1923 Bauhaus. While the Bauhaus neighborhood stands in stark contrast with Weimar’s urban present, it very much shapes the future of the German city, both materially and ideologically. As Törten concomitantly stands for production as well as “gesundes und wirtschaftliches Wohnen” (healthy and economic living), the Bauhaus symbolizes the Gesundung (recovery) of the German state and economy.

IV. Bauhaus film: László Moholy-Nagy’s City Symphonies

Hungarian artist and scholar László Moholy-Nagy joined the Bauhaus in 1923 and soon became celebrated for his experimental works in printing, photography, and film. His artistic credo was to merge art and technology and to provide a “new way of seeing, and hence a new version of utopia” (Washton Long 51). The modern city was one of the principal objects of this Moholyian “new way of seeing” and thus, in the late 1920s, Moholy-Nagy became “one of the founders of the city symphony genre” (Hagener 46). The avant-garde city symphonies aimed at the “cinematic exploration of both the most spectacular constructions and the mundane elements of urban modernity” (Jacobs, Kinik et al. 30) combined with social critique and self-reflection. The main motifs of the genre included “motorized traffic and crowds, industrial activity and leisure, high-rise structures and skyscrapers, billboards and shop windows” (27), but also the depiction of social contrasts and the marginalized poor of the city. According to Malte Hagener, this tragic ambiguity of urban life appears in Moholy-Nagy’s films, which “present the modern city as a complex and multi-dimensional environment that can never be grasped in its entirety” (54).

In a more critical fashion, I argue that Moholy-Nagy’s city symphonies, rather than merely documenting the diversity of urban space in a (hyper-)realistic and self-reflective manner, juxtapose the “old” and the “modern” within a bio-functionalist, utopian narrative. Moholy’s Impressions of the Old Marseille Harbor (Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen) from 1929, the Berlin Still Life (Berliner Stilleben) from 1932, and the Urban Gypsies (Groß-Stadt-Zigeuner) of the same year demonstrate how the artist’s discursive and aesthetic toolkits aim at animating this dichotomy and thereby suggest a normative endorsement of biopolitical modernization.

At the beginning, Impressions of the Old Marseille Harbor shows a map of the Mediterranean city. Following a similar trajectory as Wie wohnen wir gesund und wirtschaftlich?, the cartographic aerial shot slowly zooms in on the dynamic streets of Marseille filled with cars, trams and hurrying pedestrians. We then see a sequence of close-ups of slower-paced figures, which appear as anomalies within the constant flow of the traffic: a woman opening an overflowing manhole, a horse-drawn carriage transporting people who could be Ursari Roma, and a leg amputee. Moholy-Nagy presents the streets and faces of the Marseille port from different angles and distances until the camera reaches the grandiose metal construct of the city’s transporter bridge (pont transbordeur). Moholy-Nagy was fascinated by this modern “architecture-machine” (Simay 2), which inspired both his filmic and photographic works. For Philippe Simay, Moholy’s 1929 photograph of the bridge “celebrates the potentials of the modern” and simultaneously interrogates the uncertain future of human experience in the modern world (3). This ambivalence does not appear in Moholy’s Impressions. Just as the crane of the Törten construction (see figure 6), the bridge is presented from different angles and appears both optically and symbolically superior to the Vieux-Port (see figure 7). The images of the “architecture-machine,” the endless skies and the sea suddenly disappear, and the camera returns to the crowded harbor streets of Marseille, with children playing and elderly sitting on the pavement. Sudden close-ups of waste and debris, nudity and urination dominate the final scenes of the film. The work appears as a filmic struggle between the idealized and colossal modern and the poverty-stricken and chaotic old.

Similar motifs feature in Moholy’s Berlin Still Life, which documents the deprivation of the Weimar working class with the Mietskaserne tenement) as a spatialized realm of misery. Comparing this piece to the first part of Wie wohnen wir gesund und wirtschaftlich?, the imageries appear almost identical (see figures 8 and 9): dark tenement yards, children playing in the dirty streets, a cat urinating; similar angles and camera movements. Moholy-Nagy does not interrogate the structural causes of the embodied poverty and marginality he presents to the viewer. As Malte Hagener suggests, “the overall structure of the film accepts poverty and misery as given conditions, the roots and causes of social imbalance remain beyond the scope of the film” (50). Moholy-Nagy solely offers a filmic “pathology of space” (cf. Lefebvre 99) in the course of which a number of biopolitical themes such as the housing shortage, disease, and child neglect enter the picture within a distinctive discursive as well as aesthetic framework.

The theme of social hygiene reappears in Moholy-Nagy’s Urban Gypsies, albeit problematically presented through racialized Romani characters (see figure 10, cf. Baumgarten 140-141; Reuter 166-168; Hadziavdic, Hoffmann 702): gambling men, children playing in the dust, violent Romani women, the “gypsy fortune-teller” and the vagrant, horse-riding Rom contrasted with cutaways of inner-city car traffic. Moholy’s video collage does not simply draw on preexisting perceptual conventions and patterns like many early filmic works of Romani communities did (cf. Reuter 166): Urban Gypsies evokes the camp as a space of alterity, placelessness, poverty, and mystery with sudden cutaway scenes of an emerging post-industrial city (cf. Hadziavdic, Hoffmann 705).

Hagener offers two possible interpretations of this piece: Moholy’s goal is either to expose the appalling living conditions that prevail in the Romani camp or, he sees the site as a potential realm of artistic experiment (Hagener 51). I propose that regardless of which interpretation we choose, Urban Gypsies reproduces racial stereotypes along with threat scenarios of social hygiene and thereby inscribes such narratives onto the Romani body. Thus, poverty and insecurity here are not only embodied, but both essentialized and racialized.

While the Moholy-Nagy films and Wie wohnen wir gesund und wirtschaftlich? represent two genres with great cinematographic differences, many of their frames propagate the very same biopolitical themes and motifs. Camille Bui argues that “the avant-garde mise-en-scène of city space not only reflects urban modernity but takes part in its invention”, creating “the specific scopic regime of modernity” (744). To expand on Bui’s observations, I propose that Moholy-Nagy, in a distinctive avant-garde manner, not only reflects biopolitical modernity as a leitmotif of the (Dessau) Bauhaus, but also takes part in its invention. Film thus becomes a site of spatialized biopolitics: It not only documents, but also co-creates modern biopower.

Urban Gypsies is especially fascinating in this context, as – by reinforcing both racialized tropes and biopolitical concerns –, it aesthetically captures the symbiotic relationship between biopolitics and racism (as pointed out by Foucault in Society Must Be Defended). As mentioned earlier, while revealing the omnipresence of biopower in modern society, biopolitical studies concomitantly uncover the tension between the normative imaginary of the best possible life and the practical motivation behind (state) measures for population health and control. At the same time, Foucault problematized another paradox of biopower, namely the establishment of racial caesuras that introduce a break between the own “good” and hence protectable population and the “bad” population, the population of the enemy Other (Foucault, Society 254-255). The bad population is deemed not only dangerous, but also unworthy of (the best possible) life. Analyzing Urban Gypsies through a Foucauldian lens, Moholy’s film seems to offer a problematic aesthetic depiction of biopolitical caesuras and is therefore a quintessential cultural artifact for the understanding of both the Bauhaus and Weimar Germany in general.

V. Conclusion and Outlook: Traveling Forms

While the practical achievements of the Bauhaus undoubtedly enhanced individual human lives, the collectivist objective of its Dessau period should be seen in critical light of the ever-expanding spatialization of biopower. This has important implications beyond the Weimar Republic, considering the global influence of the school as well as the “after-lives” of those Bauhaus artists who fled Nazi Germany. Gropius and Moholy-Nagy’s work in the Unites States prolongs the school’s trajectory towards state capitalism: For, as Nicole Huber suggests, the Chicago-based “New Bauhaus” directed by Moholy-Nagy “devoted itself yet again to developing a new synthesis between art and technology” and thus “responded to the challenges of corporate America […]” (166). Leaving behind the shadows of both post-war Weimar and the Third Reich, the American Bauhaus addressed the post-1945 U.S. “industrial-military complex in terms of culture and control” (Huber 166), just as it had once followed the policies dictated by the Weimar state.

Further South, Hannes Meyer’s proposal of a colonia obrera (workers’ estate) in Lomas de Becerra in the outskirts of Mexico City suggests similar continuities. With his project based on the plans of Dessau-Törten (Franklin Unkind 33-34), Meyer intended to provide healthy and comfortable living for the local working class in order to promote greater productivity in the surrounding industry (32; cf. Lazo 58). He believed that the living conditions of the blue collars impacted their work, proposing that “a worker who lives in his house in comfort, who sleeps eight hours […], who has a […] bathroom, [and] a balcony to rest […] will be more productive at his workplace” (Meyer 71, as cited by Franklin Unkind 33). This new fusion of workplaces and dwelling-places could never take shape in Lomas de Becerra: Meyer abandoned his project in the outskirts of the rapidly growing capital as he was appointed architectural secretary of the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS), commissioned to oversee the planning and building of hospitals and clinics (Lazo 58).

Beyond Gropius and Moholy-Nagy in the U.S. and Meyer in Mexico, the Bauhaus “diaspora” included among others Wassily Kandinsky in Russia, Marcel Breuer at Harvard, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in Chicago and Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky in Vienna. We can find Bauhaus neighborhoods not only in Berlin, Dessau or Frankfurt, but also in Mexico City, Bujumbura or Tel Aviv (Clammer 128). This transboundary network of neighborhoods exemplifies Lefebvre’s “global space” filled with “the worldwide, homogenous and monotonous architecture of the state” (Lefebvre 126). In The Production of Space, Lefebvre highlights the quintessential role of the Bauhaus in mastering global space in vivid terms: in the Bauhaus realm of “nature rediscovered, with its sun and light, beneath the banner of life, metal and glass still rise above the street, above the reality of the city” (305). Here, Lefebvre ironically points out the tension between the school’s credo of enhancing individual human lives and its detachment from the everyday micro-reality of urban living for the sake of a statist grand-project.

By further fleshing out this tension in the operation of the late Bauhaus, this paper demonstrated how the Dessau school catered to the economic incentives of Weimar Germany and conformed to the state’s biopolitical agenda. These findings contribute to the scholarship that argues against an overemphasis on totalitarian politico-economic settings in biopolitical studies (cf. Dickinson 1; Dubreuil 96) and point to the fact that – to borrow a Derridean term – the specters of biopower are omnipresent in our urban modernity. They not only haunt the camp and the plantation (cf. Agamben; Mbembe), but also the city, the house, and the screen.

While the Bauhäusler introduced in this paper clearly articulated the vision of “[t]he best possible life for as many people as possible” (Bundespräsidialamt 5), their practical achievements adopted a new strategic orientation towards the industry and “were engineered from the very outset to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of production itself” (Gilloch 188), both in Germany and the Americas. Against the backdrop of this discrepancy, the biopolitical rereading of the Bauhaus expands on Lefebvre’s critique of the architects and planners of “global space” and offers a tribute to Lefebvre’s programmatic vision of “differential space.” Lefebvre pleaded for a political movement that challenges the centralized state “as the power that controls urbanization, the construction of buildings and spatial planning in general […], by grass-roots opposition, in the form of counter-plans and counter-projects designed to thwart strategies, plans and programs imposed from above” (Lefebvre 383). Lefebvre’s differential space is self-governed by a heterogenous multiplicity of dwellers on a local level, in spite of their potentially conflicting interests. It is a space of nonuniformity, desire, creativity and art; much like the early Bauhaus.

Since its centennial, the Bauhaus has once again become a source of inspiration, an idealized antidote to the recurring housing crises of our time. Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, has even initiated the foundation of a “New European Bauhaus” to build a more “humane” 21st century (European Commission). Rather than discrediting such ideas, this paper offers a more nuanced perspective of a movement that so greatly influences our contemporary debate on dwelling. Learning from both the successes and failures of the Bauhaus may provide us some guidance to outline a more humane and a potentially more differential urban future.

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio (1995): Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Heller-Roazen, D., Trans.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998.

Bauhaus Dessau (n.d.): Dessau-Törten Housing Estate (1926–28), Walter Gropius. Retrieved from: https://www.bauhaus-dessau.de/en/architecture/bauhaus-buildings-in-dessau/dessau-toerten-housing-estate.html

Baumgartner, Gerhard. “„Zigeuner“-Fotografie aus den Ländern der Habsburgermonarchie im 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhundert.” Inszinierung des Fremden, Fotografische Darstellung von Sinti und Roma im Kontext der historischen Bildforschung, eds. Peritore, Silvio and Frank Reuter, Heidelberg: Dokumentations- und Kulturzentrum Deutscher Sinti und Roma, 2011, pp. 133-161.

Berghausen, Nadine. The Bauhaus Designing Life. 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.goethe.de/en/kul/des/dos/bau/21356390.html

Bundespräsidialamt. Speech by Federal President Frank Walter Steinmeier at the opening festival marking the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus in Berlin on 16 January 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.bundespraesident.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Reden/2019/01/190116-Bauhaus-100-Jahre-Englisch.pdf;jsessionid=6570729126EB4117371DE416385DEA89.2_cid371?__blob=publicationFile

Bui, Camille. “L’invention d’une rencontre entre le cinéma et la ville : la « symphonie urbaine » au tournant des années 1930.” Annales de Géographie, no. 695-696, 2014, pp. 744-762.

Clammer, John. “Bauhaus in Asia: Model or Modernist Past?” Bauhaus and the City: A contested heritage for a challenging future, eds. Colini, Laura and Frank Eckardt, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2011, pp 113-128.

Colini, Laura and Frank Eckardt (eds.). Bauhaus and the City: A contested heritage for a challenging future. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2011.

Dickinson, Edward Ross. “Biopolitics, Fascism, Democracy: Some Reflections on Our Discourse About “Modernity.”” Central European History, vol. 37, 2004, pp. 1 – 48.

Dubreuil, Laurent. “Leaving Politics: Bios, Zoe, Life.” Diacritics, vol. 36, no. 2, 2006, pp. 83-98.

Eckardt, Frank. “Bauhaus and the “New Frankfurt”: Limited opportunities, limited concepts.” Bauhaus and the City: A contested heritage for a challenging future, eds. Colini, Laura and Frank Eckardt, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2011, pp. 18-30.

Eckart, Wolfgang. “Öffentliche Gesundheitspflege in der Weimarer Republik und in der Frühgeschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.” Public Health. eds. Schwartz, Friedrich et al. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 1991, pp. 221-237.

European Commission. “A New European Bauhaus: op-ed article by Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission.” 15 October 2020. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/AC_20_1916

Forgács, Éva. Bauhaus idea and Bauhaus politics. Budapest, New York, NY: CEU Press, 1995.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality (Volume I). New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1990.

————. (1975-6): Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-76. Translated by David Macey, New York, NY: Picador, 2003.

————. (1977-8): Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-1978. Translated by Graham Burchell, New York, NY: Pelgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Franklin Unkind, Raquel. “Experiencias de urbanismo: los proyectos urbanos de Hannes Meyer en México (1938-1949) [Experiences of urban planning: Hannes Meyer’s urban projects in Mexico (1938-1949)].” dearq 12, 2013, pp. 28-41.

Gilloch, Graeme. “Seen From the Window: Rhythm, Improvisation and the City.” Bauhaus and the City: A contested heritage for a challenging future, eds. Colini, Laura and Frank Eckardt, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2011, pp. 185-202.

Goergen, Jeanpaul. “»wirklich alles wurde unseren wünschen entsprechend gemacht«: Das Bauhaus in Dessau im Film der zwanziger Jahre.” Maske und Kothurn, vol. 57, no. 1-2, 2011, pp. 109–122.

Gropius, Walter. “Program of the Staatliches Bauhaus.” Retrieved from: https://bauhausmanifesto.com.

Hadziavdic, Habiba and Hilde Hoffmann. “Moving images of exclusion: Persisting tropes in the filmic representation of European Roma. Identities.” Global Studies in Culture and Power, vol. 24, no. 6, 2017, pp. 701-719.

Hagener, Malte. “László Noholy-Nagy and the City (Symphony).” The City Symphony Phenomenon: Cinema, Art, and Urban Modernity between Wars, eds. Jacobs, Steven et al. London, New York, NY: Routledge, 2019, pp. 45-55.

Harvey, David. “Afterword.” In Lefebvre, H.: The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Oxford, Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1991, pp. 425-434.

Hau, Michael. “Constitutional Therapy and Clinical Racial Hygiene in Weimar and Nazi Germany.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, vol. 71, no. 2, 2015, pp. 115–143.

Huber, Nicole. “Tracing Transdisciplinary Research: Urban Laboratories from Weimar to the American West.” Bauhaus and the City: A contested heritage for a challenging future, eds. Colini, Laura and Frank Eckardt, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2011, pp. 163-184.

Isaacs, Reginald. Gropius: An Illustrated Biography of the Creator of the Bauhaus. Boston, MA: Bulfinch Press, 1983.

Jacobs, Steven et al. (eds.): The City Symphony Phenomenon: Cinema, Art, and Urban Modernity between Wars. London, New York, NY: Routledge, 2019.

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. (ed.): Bauhaus Culture: From Weimar to the Cold War. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. “Beyond Cold War Interpretations: Shaping a New Bauhaus Heritage.” New German Critique, No. 116, 2012, pp. 11-24.

Koehler, Karen. “The Bauhaus Manifesto: Postwar to Postwar From the Street to the Wall to the Radio to the Memoir.” Bauhaus Construct: Fashioning Identity, Discourse and Modernism, eds. Saletnik, Jeffrey and Robin Schuldenfrei, London, New York, NY: Routledge, 2009, pp. 13-36.

Lazo, Pablo. “Dislocating Modernity: Two Projects by Hannes Meyer in Mexico.” AA Files, no. 47, Summer 2002, pp. 57-63.

Lefebvre, Henri. (1974): The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Oxford, Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1991.

Mbembe, Achille. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture, vol. 15, no. 1, 2003, pp. 11-40.

Meyer, Hannes. “Higiene industrial y arquitectura industrial.” Trabajo y Previsión Social, no. 70, 1945.

Posman, Sarah. “Life Escaping: Foucault, Vitalism, and Gertrude Stein’s Life-Writing.” Understanding Foucault, Understanding Modernism, ed. Scott, David, New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2017, pp. 177-195.

Rauterberg, Hanno. “Die Zukunft ist jetzt.” Die Zeit. No. 53, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.zeit.de/2016/53/bauhaus-jubilaeum-100-hochschule-gestaltung-kultur

————. “Ins Zeitlose entrückt.” Die Zeit. No. 04, 16 January 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.zeit.de/2019/04/bauhaus-architektur-100-jahre-modernismus-mythos-revolution

Rennie Short, John. “Crystallizing the Urban Legacy of the Weimar Bauhaus.” Bauhaus and the City: A contested heritage for a challenging future, eds. Colini, Laura and Frank Eckardt, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2011, pp. 142-152.

Reuter, Frank. “Fotografische Repräsentation von Sinti und Roma: Voraussetzungen und Traditionslinien.” Inszinierung des Fremden, Fotografische Darstellung von Sinti und Roma im Kontext der historischen Bildforschung, eds. Peritore, Silvio and Frank Reuter, Heidelberg: Dokumentations- und Kulturzentrum Deutscher Sinti und Roma, 2011, pp. 163-221.

Saval, Nikil. “How Bauhaus Redefined What Design Could Do for Society.” The New York Times. 04 February 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/04/t-magazine/bauhaus-school-architecture-history.html

Schmidt, Thomas. “Auf Nietzsches Schultern.” Die Zeit. No. 16, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.zeit.de/2019/16/bauhaus-weimar-jubilaeumsjahr-architektur-museum

Silverman, Dan. “A Pledge Unredeemed: The Housing Crisis in Weimar Germany.” Central European History, vol. 3, no. 1-2, 1970, pp. 112-139.

Simay, Philippe. “Double Vue, Moholy-Nagy et le pont transbordeur.” Le pont transbordeur de Marseille, eds. Bon, François et al., Paris: Éditions Ophrys, 2013. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/5251919/Double_vue_Moholy_Nagy_et_le_pont_transbordeur

Stanek, Lukasz. Henri Lefebvre on Space: Architecture, Urban Research, and the Production of Theory. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

————. “Biopolitics of Scale: Architecture, Urbanism, the Welfare State and After.” The Politics of Life: Michel Foucault and the Biopolitics of Modernity, eds. Wallenstein, Sven-Olov and Jakob Nilsson, Stockholm: Iaspis, 2013, pp. 105-122

Thaler, Michael. “Medicine and the Rise and Fall of the Weimar Republic: Health Care, Professional Politics, and Social Reform.” German Politics & Society, vol. 14, no. 1, 1996, pp. 74-79.

Tomita, Hideo. “Hannes Meyer’s “Biological” Concept and its Loosening Influence on Form.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, vol. 7, no. 2, 2008, pp. 179-185.

Van Leeuwen, Theo. Introducing Social Semiotics. New York, NY: Routledge, 2005.

Wallenstein, Sven-Olov. Biopolitics and the Emergence of Modern Architecture. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008.

Walter, Hannes. “„Volksseuche“ oder Randerscheinung? Die „Kokainwelle“ in der Weimarer Republik aus medizinhistorischer Sicht.” NTM Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik und Medizin, no. 25, 2017, pp. 311-348.

Washton Long, Rose-Carol. “From Metaphysics to Material Culture: Painting and Photography at the Bauhaus.” Bauhaus Culture: From Weimar to the Cold War, ed. James-Chakraborty, Kathleen, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2006, pp. 43-62.

Weindling, Paul. “Weimar eugenics: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics in Social Context.” Annals of Science, vol. 42, no. 3, 1985, pp. 303-318.

Winkelmann, Arne. “Impulse vom Bauhaus: Wohnen damals und heute.” Architektur macht Schule, 26 September 2016, Architektenkammer Baden-Württemberg, Lecture.

Film material

Jahn, Ernest. Wie wohnen wir gesund und wirtschaftlich. Humboldt-Film GmbH [Bauhaus-Archiv]. 1928. Retrieved 23 July 2020 from: https://vimeo.com/292710660; https://vimeo.com/292713246; https://vimeo.com/292714014; https://vimeo.com/292714585.

Moholy-Nagy, Lálszló. [LSpiro]. Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen (Vieux Port) (Impressions of the Old Marseille Harbor). 1929. Retrieved 06 August 2020 from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QbWu3EMvUVc.

————. [Moholy-Nagy Foundation]. Berliner Stilleben. 1932. Retrieved 11 November 2020 from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1JbGMHdofwM&feature=emb_title.

————. [Johannes Kretz]. Großstadtzigeuner (Urban Gypsies). 1932. Retrieved 08 August 2020 from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2QiXpUCCA0&t=230s; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=07HgKU15uk4