Digital Humanities as Translation: Visualizing Franz Rosenzweig’s Archive

Matthew Handelman

Abstract

This article consists of a theoretical framework for and a demonstration of the process of visualizing the finding aid to Franz Rosenzweig’s archive at the University of Kassel, which contains metadata describing documents and letters pertaining to the German-Jewish philosopher, pedagogue, and translator. Its main contention is that much of the work undertaken by the digital humanities, especially data conversion, refinement, and visualization, involves salient yet undertheorized moments of translation. Indeed, Rosenzweig’s own theory of translation, which advocates radical formal fidelity to the original, offers a revealing lens to understand the potential and limitations of visualizing the metadata of his archive – a lens I use to guide my translation of the archival metadata. As I show, the visualization’s inclusion of peripheral voices in his archive implied by such fidelity exposes a correspondence between the journalist Siegfried Kracauer and educator Ernst Simon that calls the ideological implications of Rosenzweig’s theory of translation into question. This dialectical movement between theory and praxis, metadata and material archive, I contend, is the promise and productive threat that the digital humanities represent for German Studies: as much as the digital humanities pave new inroads for research, they also require and return us to critical concepts central to German literary and cultural discourse, such as translation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the graduate students at the University of Pennsylvania for their invitation to give the short talk and demonstration, out of which this article evolved, and Thomas Padilla at Michigan State University Libraries for his help preparing this demonstration. My thanks and gratitude are also due to Brigitte Pfeil and Sabine Wagener at the Universitätsbibliothek-Landesbibliothek and Murhardsche Bibliothek in Kassel, Germany for their continuing help navigating Rosenzweig’s archive and to Suhrkamp Verlag, for generously granting me permission to cite from Siegfried Kracauer’s letters held therein.

The finding aid for Franz Rosenzweig’s Teilnachlass embodies the promise as well as many of the questions and anxieties that the digital humanities increasingly bring to the field of German Studies.[1] Ostensibly, the document is a thirty-six-page list of letters and documents in Rosenzweig’s archive housed at the University of Kassel’s library, their catalogue numbers, authors, recipients, dates, and places of composition. The aid assists staff and researchers sort through the nearly one thousand documents left by the preeminent German-Jewish philosopher, theologian, and translator Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929) and sold to the University in 2006.[2] On the one hand, the finding aid’s digital potential lies in the wealth of metadata that it contains. Such metadata, and the documents they describe, not only lend themselves to data visualization through digital network and geospatial mapping tools, but also indicate new inroads to understand Rosenzweig more comprehensively as a seminal yet often underestimated modernist intellectual, as well as many of his early-twentieth century Jewish and Christian peers, including Martin Buber, Ernst Simon, Rudolf Ehrenberg, and Eugen Rosenstock.

On the other hand, the finding aid and its digital manipulation may be a cause of apprehension and anxiety for some scholars, not the least because working with this relatively inaccessible PDF entails considerable time, conversion, and translation. Yet if working with the finding aid is a matter of translation and conversion, then Rosenzweig’s life and work provide not only ideal material for digital scholarship, but also insight into how one can best proceed with such an intervention: in 1913, Rosenzweig nearly converted to Christianity and, after 1924, published extensively on translation.[3] Indeed, his theory of translation, which calls for radical linguistic fidelity to the original, offers a unique opportunity to reflect on the deeper transformations, which take place in the digital humanities which are often glossed by seemingly innocuous terms such as “cleaning” or “refining,” and about which we may, undeniably, have cause for concern. Amidst ongoing debates over what digital tools actually reveal in humanities research and how they are redefining the academy, the translation of the finding aid from a textual list to a visual timeline, map, and network renders visible neglected sources and conversations that intervene in and, hence, force us to revisit questions central to the humanities, in particular translation theory.[4] Moreover, these visualizations underscore not only the relevance, but also the necessity of the theoretical and critical approaches to translations that serve as mainstays in German cultural and literary discourse—from “Abrogans” to Schleiermacher and Rosenzweig, and, now more than ever, in the digital age.

This article consists of a proposed theoretical framework for and a demonstration of the process of visualizing Rosenzweig’s finding aid and a meta-reflection on the results produced by the digital tools Tabula, OpenRefine, and Palladio. Given the unorthodox form and content of the following analysis, the reader may find it useful to keep in mind a few questions that I view as dialectically entwined. In terms of the humanities, what, if anything, can data visualization tell us about Rosenzweig’s life and work, or about German-Jewish history more broadly? In terms of digital scholarship, how does Rosenzweig’s theory of translation reveal and help us conceptualize the inadvertent additions or elisions that hide behind the otherwise everyday jargon of “extracting,” “converting,” “refining,” and “cutting, copying, and pasting” data? How, ultimately, do a discipline that is deeply concerned with the question and consequences of technology—such as German Studies—and an emerging set of research tools that help ask novel hermeneutic questions and force us to revisit key critical tropes—such as the digital humanities—reciprocally inform each other both practically and theoretically? In addressing these issues, I contend, first, in the words of Lawrence Venuti, that digital work entails an analogous “choice concerning the degree and direction of the violence” that we do to a text through translation and, second, that the digital humanities are—or should be seen to be—embedded in the complex histories and theorizations of translation itself (15).

Not just the Kassel finding aid, but also Rosenzweig as a thinker and historical figure present ideal subjects for a digital project. Rosenzweig was, for instance, a prolific letter writer and his work is mostly in the public domain, in need of preservation, and highly interdisciplinary: drawing on the German Idealist and neo-Kantian philosophical traditions, theological sources from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the natural sciences and mathematics, and German literature and culture.[5] Visualizing Rosenzweig’s archive thus works in the service of larger, international efforts to bring Rosenzweig into, and help preserve his legacy through, the digital age, which consist in creating and curating an online digital edition of his magnum opus, The Star of Redemption (1921) and digitizing his archives around the globe.[6] My aim here, however, is not to make a strict thematic argument about Rosenzweig or his theory of translation, which critical literature already aptly covers.[7] Instead, by building on recent forays from German Studies into the digital, the visualization and theorization of Rosenzweig’s archive within the framework of translation theory emphasizes the timeliness of traditions—religious then and humanistic now—at historical moments in which these practices may seem increasingly archaic and irrelevant.[8] The visualization of Rosenzweig’s archive thus leads us not only back to the material archive by revealing letters long thought lost from the journalist and film theorist Siegfried Kracauer to the educator and philosopher Ernst Simon. It also returns us to the problems of history and the archive, and the relationship between language and truth in the age of media and technology—a relationship raised in Buber and Rosenzweig’s collaborative Bible translation and famously criticized by Kracauer.

Conversely, what Rosenzweig brings to debates in the digital humanities is a critical sensitivity to the consequences of the processes and terms—often employed unreflectively by digital humanists—which new technologies offer to humanities scholarship. These processes range, for instance, from the removal of unwanted metadata or changes in its structure and formatting (mentioned above as data “cleaning” or “refining”) to the large-scale, algorithmic manipulation of texts and text corpora in topic modelling.[9] More recent criticism, such as that from Lisa Gitelman and Virgina Jackson, has begun to fill this critical lacuna, interrogating the “unnoticed assumption that data are transparent, that information is self-evident, the fundamental stuff of truth itself” and the constructed nature of working with data (2).[10] A similar inclination motivates the demonstration and analysis presented below: that the problem of translation lies unresolved and irreducible at the heart of much of the work being done under the name “the digital humanities,” whether these translations involve moving data from one format or media to another or in transforming questions in the humanities into quantities and datasets legible to a computer. To borrow Venuti’s term for translators in Anglo-American translation discourse, a certain invisibility shrouds much digital humanities work and the following article attempts to reveal these conspicuous yet often unseen assumptions and processes in three phases (1-34). First, it outlines the basis, context, and potential contribution of Rosenzweig’s theory of translation. Second, it demonstrates the basics of visualizing Rosenzweig’s finding aid using tools chosen for their availability and ease of use. Third, it analyzes how Rosenzweig’s theory of translation not only applies to, but also is revised by the new perspectives provided by the visualization. My goal, however, is not just to provide new information about Rosenzweig, nor is it to defend the humanities against new incursions made by technology. Rather, my goal is to show that both the promise and productive threat of the digital humanities lie in how they both reinstate and radicalize concerns central to the humanities, such as the problematic and constructed nature of the archive. If the digital humanities are redefining the way we conduct humanities scholarship, then they also require some of the more compelling discourses in the humanities, and in German Studies, to comprehend this very same redefinition.

1.

Translation emerges as a central concern for Rosenzweig later in his career, after he had gained notoriety in the early Weimar Republic as a public intellectual and educator through The Star of Redemption and his leadership at the Freies Jüdisches Lehrhaus in Frankfurt am Main. Rosenzweig’s translation legacy rests today on his contribution to translating the Hebrew Bible with Martin Buber, which Buber, after Rosenzweig’s death in 1929, finished in Israel in the 1960s. While in letters and published texts Buber and Rosenzweig produced a wealth of theory on translation, the foundation of Rosenzweig’s own thoughts on the subject builds on his translation of the medieval Hebrew poet Jehuda Halevi in 1924.[11] The “Afterword” to these translations distils two methodological principals advantageous for the visualization of his archive and also indicative of the cultural context to which they respond. In general, the turn to translation that Rosenzweig systematizes in his work on Halevi continues the philosophical-intellectual project inaugurated by The Star of Redemption in 1921. Focusing on the interrelationship between philosophy and theology, Rosenzweig argues for the neglected philosophical significance of the temporal here-and-now of lived religious experience and thereby maintains that, even in a modern and secular world, Judaism remains a philosophically cogent system of revelation and redemption.[12] Both Rosenzweig and his work on translation are representative of broader religious renewal programs in Christianity and Judaism around the First World War. In the Jewish context, these discourses centered on the restoration of Jewish identity and faith in the wake of the historical processes of emancipation and assimilation and in a Germany rapidly modernizing into a mass, protestant-secular, capitalist society. The subtext to Rosenzweig’s work on translation thus reads as an attempt to enable traditional forms of knowledge and experience, such as medieval Hebrew poetry, to retain their original revelatory message and aesthetic power in a society and culture in which the very ideas of knowledge and experience were radically changing or had already changed.

The first methodological consideration applicable to our work on Rosenzweig’s archive is the central tenet of his translation theory as he articulates it in 1924: a successful rendering into German should not “Germanize what is foreign [nicht das Fremde einzudeutschen],” but rather “make foreign what is German [das Deutsche umzufremden]” (“Afterword” 170 and “Nachwort” 154). But Rosenzweig represents neither the first nor the only theorist to advocate a practice of foreignization in German translation. Friedrich Schleiermacher frames, for instance, translation as a choice between moving the foreign language towards the reader (e.g. Luther’s “common man”) and bending the reader to the foreign language—Schleiermacher advocates the latter.[13] In contrast to Schleiermacher’s desire to find the closest approximation for foreign terms, Rosenzweig’s theory of foreignization sacrifices the poetic subjectivity of the translator for the sake of maintaining the linguistic—syntactic and semantic—integrity of the original:

So it was not my aim to make the reader believe that Jehuda Halevi composed in German, nor that he composed Christian church songs, nor that he is a poet of today, even if only a Familienblatt poet of today—all this as far as I can see the aims of my predecessors in translation, especially the most recent ones. Instead, these translations want to be nothing but translations. Not for a moment do they want to make the reader forget that he is reading poems not by me, but by Jehuda Halevi, and that Jehuda Halevi is neither a German poet nor a contemporary. In a word: this translation is not a free rendering [Nachdichtung], and yet if here and there it is so, then only for need of rhyme. Basically my intention was to translate literally, and in approximately five-sixths of these lines of verse I may have succeeded (“Afterword” 170 and “Nachwort” 153).

What Rosenzweig has in mind is not a modernization of Halevi’s poetry, as his contemporaries such as Emil Cohn had undertaken in 1920. Instead, the “Afterword” aims at creating a path, through language and literature, for primarily assimilated German Jews to reconnect with an otherwise forgotten or obscured Jewish tradition and an unintelligible Jewish language. Yet the passage touches on more than just Jewish identity in modern Germany, as the curious word “Nachdichtung,” not fully captured by “free rendering,” indicates. Rosenzweig also hints at a sensitivity to the mediation (“Dichtung”) after (“Nach-”) the aesthetic fact as well, which may obscure or estrange Halevi’s message. Indeed, phonetic and structural differences between languages, as Rosenzweig recognizes in bringing poetry from one language to another, and technical specifications in displaying data, as I note below in visualizing the finding aid with a tool like Palladio, impose limitations on the complete elimination of “Nachdichtung” imposed by the translator. Nonetheless, Rosenzweig’s theory of translation forces us to take critical account of the potential effects set in motion by “Nachdichtung,” by the elements we mediate—add, subtract, or obscure—in translation and data visualization.

The second method the “Afterword” brings to the digital humanities relates to the temporal displacement of original text and translation, in particular in the context of Jewish thought in the diaspora. Along with an elimination of “Nachdichtung,” Rosenzweig’s translation program forwards the practice of “Musivstil” (“inlaid-style”), which Halevi himself employed by including frequent Bible citations and which Mara Benjamin elucidates as “the appearance of epochs that are literally in the age of minority” or subordinate to the text’s epoch (80-83). In Rosenzweig’s rendering, “Musivstil” transforms a literary technique into a philosophical antidote to the metaphysical state of Jewish exile:

All Jewish poetry in exile scorns to ignore this being-in-exile. It would have ignored its exile if it ever, like other poetry, took in the world directly. For the world which surrounds it is exile, and is supposed to remain so to it. And the moment that it would surrender this attitude, when it would open itself to the inflow of this world, this world would be as a home for it, and it would cease to be exile. This exiting of the surrounding world is achieved through the constant presence of the scriptural word. With the scriptural word another present thrusts itself in front of the surrounding present and downgrades the latter to an appearance, or more precisely, as parable (“Afterword” 177 and “Nachwort” 161).

Enabled by the “foreignness” and “exile” that “Nachdichtung” tends to obscure, the passage proposes an inversion of lyrical time: the “scriptural world” becomes privileged over the “surrounding present,” indeed “trusts itself in front of” that present, which, so subordinated, only signifies the Biblical past. “Musivstil” thus does not “scorn” mediation as such. Rather, as an aesthetic program it expands translation as the mediation of geographic and linguistic distance to include the mediation of temporal difference between the past “scriptural word” and the present “being-in-exile.” Through this temporal inversion, Rosenzweig hopes to expose and reconnect contemporary readers to a religious truth (i.e. the word of God) covered up by Jewish assimilation into Christian society and the homogenizing and secularizing forces of modern mass culture.

Rosenzweig’s aims of eliminating “Nachdichtung” and retaining temporal difference in translation not only inform the decisions guiding the visualization outlined below, but also bring the contours of my conceptual translation of Rosenzweig’s theory into focus. As Rosenzweig attempts to avoid transforming Halevi and his poetry into things that they are not (“a German poet” or “Christian church songs”), so too I strive to avoid translating the finding aid into visualizations that suggest that the finding aid is complete, contains no mistakes, or represents only documents to and from Franz Rosenzweig. In praxis, these goals may seem obvious or trivial, but decisions regarding the retention or elimination of inconsistencies and ostensibly peripheral data points (e.g. Simon and Kracauer’s letters) are precisely where one could impose their own aesthetic and editorial paradigm, such as visual neatness or an intellectual focus on Rosenzweig alone. Similarly, as Rosenzweig’s translations work to remind his readers of the Biblical word, my translation works to render legible to readers and viewers the finding aid’s material and textual basis: the human effort that went into assembling, preserving, and cataloguing the archive and the intentional yet ultimately, historically contingent assemblage of documents and information that the finding aid represents. Indeed, such a comparison reveals the stark difference between Rosenzweig’s project and my own: to render faithfully the word of God and, respectively, to preserve the coincidences and constructions that make up an archive. But, as we shall see below, this comparison also lays bare not only that, but also which ideological commitments and limitations are implied by past Jewish renewal movements in Germany—to reestablish a lost sense of religious truth and community—as well as by my approach to the digital humanities—to stress the enduring necessity of humanities questions and concerns when these traditions seem to be in crisis.

2.

This section outlines three stages necessary to prepare and process the finding aid to Rosenzweig’s Kassel Teilnachlass into a timeline, geospatial map, and network graph. These include extracting the data with Tabula, refining them with OpenRefine, and visualizing them with Palladio. It intends to provide an introduction and guide for scholars with similar digital humanities questions or problematic documents which they too may wish to visualize. Moreover, similar to the “Notes” (“Bemerkungen”) that Rosenzweig includes in his translation of Haveli (185-286 and 171-259), this guide and discussion also serves as a critical apparatus elucidating the choices I have made in translating the archival metadata from their “original” state (see Figure 1) and as a means of sharing these data with those scholars interested in developing, refining, and using them further. Download the finding aid here (File 1).

Certainly, a major difference in scope separates Rosenzweig’s notes, which present detailed historical, bibliographical, theological, and etymological commentary on Halevi’s poems and Rosenzweig’s translation, from what I provide below. But if one goal of our translation is preserving the legacy of German-Jewish history in the present, then we should provide as much relevant information about the entries in the archives and their translation as Rosenzweig did about the words in Halevi’s poetry. As laid out above, the translational principle followed in these remarks targets a literal translation, which, aware of its technological limitations, strives in visualization to remind readers of the once textual and archival nature of its source, replete with its inconsistencies, incongruences, and problems.

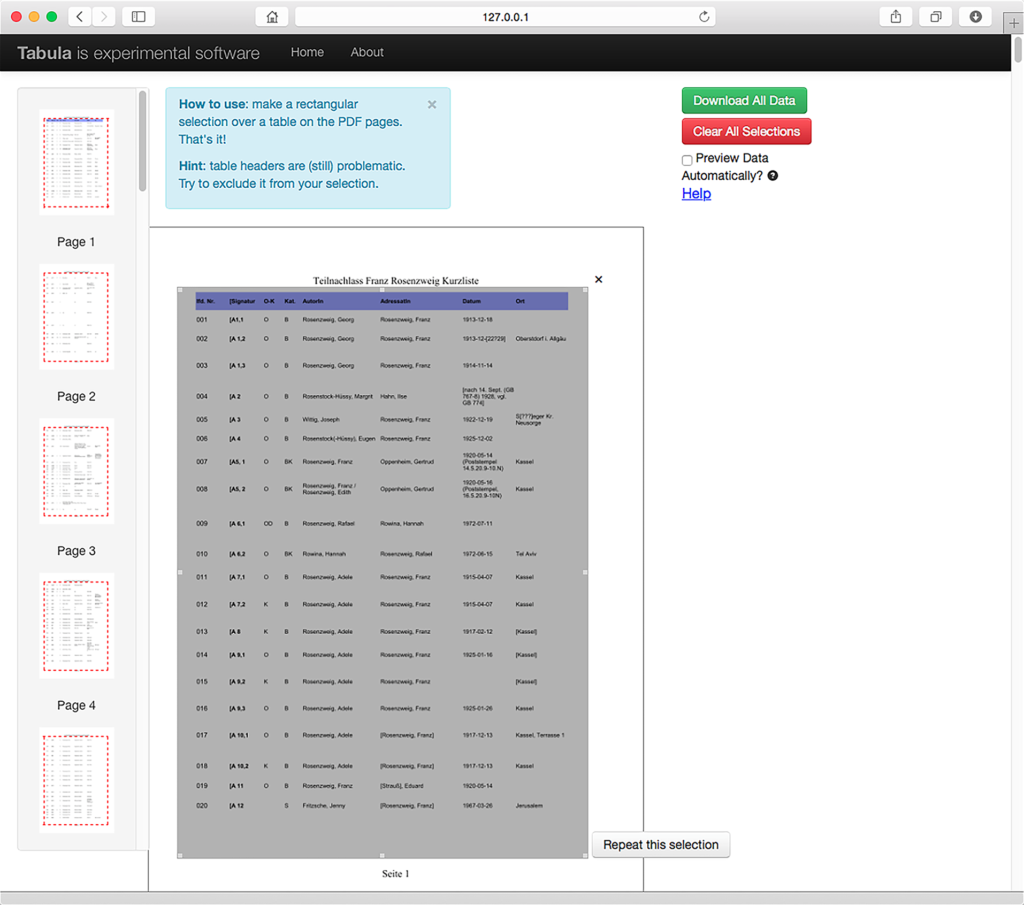

The initial step towards visualization necessitates converting the metadata in the finding aid from a PDF format into a data form legible to network visualization software.[14] As with many network analysis programs, the one I chose, Palladio, expects data to be in an Excel-style, spreadsheet format (i.e. in a CSV or XLS file). While more straightforward methods of extracting the data produce unusable results (for instance, copying and pasting from the PDF document to Excel), the free program Tabula extracts tables embedded in PDF documents and exports them as spreadsheet files. To extract the data using Tabula, we select the entire table (or range of data) in the PDF file and repeat this selection for all thirty-six pages of the finding aid (see Figure 2). Download Tabula data here (File 2).

Beyond the algorithms at work in Tabula itself, it is here that the first real question of translation arises: the data at our disposal at the stage of visualization will depend on the range of metadata we select, and thus indicate to Tabula to extract. In other words, even if the example is trivial at this stage, as translators we nonetheless make a decision regarding the scope of what materials from the finding aid we wish either to include or exclude from the visualization. In the service of literal translation, I chose to include all data points (excluding the title and page numbers) present in the PDF finding aid as available online, even as certain data points may be lacking, incomplete, or tangential to Rosenzweig in the finding aid or elided in the process of extraction.

Even with the assistance of a specialized program such as Tabula, the spreadsheet data produced remains too inconsistent for any network analysis program to read. While not always in the correct column, the extracted data must fall into eight categories: the list number, the archival signature (bin and document), a letter signifying if the document is an original (“O”) or copy (“K”), the type of document (letter “B”, work “W,” etc.), author, addressee, date, and place.[15] For our purposes, Palladio requires the data in these columns to be in three standard column formats: to create a network graph, we need columns of authors and recipients; the timeline needs dates formatted as YYYY-MM-DD; and the mapping function needs letter place names (i.e. “Kassel”) to be translated into geospatial coordinates (latitude, longitude). The main effort of translating Rosenzweig’s archive thus resides in using a data-refinement program, such as OpenRefine, to transform the data into a format accessible to Palladio.[16] As the second stage of preparing the data for visualization, I have distilled this step into various points. While I adhere to the goal of eliminating “Nachdichtung” and attempt to avoid my own intercessions on the data as translator, at least two particular translational limitations emerge during this stage pertaining to choices I make regarding date and place information.

- Before using OpenRefine, I manually rearranged data that Tabula had clearly placed in the incorrect column (see Figure 3). Download refined data here (File 3).

- One of the more striking features of the finding aid is the presence of brackets (“[“ and “]”), most likely indicating information not contained in the documents themselves, but added by archivists during the process of cataloguing the archive (Figure 4). Hence, when OpenRefine suggests standardizing variations of “Strauss, Eduard” with “(“ and “]” as “(Strauss, Eduard),” I retained the numerous variations of these archival additions (see row four in Figure 5). For simplicity, I chose to standardized the order of commas and brackets based on the most frequent usage and converted “ÄŸ” back to “ß”, after consulting the finding aid (see row three in Figure 5).

- Much of the finding aid’s metadata lacks author or recipient information, or, because it is a document, lacks obvious authorship. In such cases, as with Hans Ehrenberg’s letter to an unknown recipient or involving a document pertaining to Rosenzweig’s marriage to Edith Hahn, I added “Unknown – Recipient” and “Unknown – Author” respectively (Figure 6). Download refined author data (File 4) and refined recipient data (5), respectively.

- I have retained letter and document dates when they are mentioned. In cases where the finding aid indicates the date provided stems from the postmark (“Poststempel,” or anagrams thereof) rather than the document itself, I used the postmark dates (see Figure 7). Here, incomplete date information reveals a potential weakness in my translation: because Palladio only recognizes dates as years, months, and days (see Figure 4), I was forced to compensate for incomplete day or month information by adding the first day of the month or January. Moreover, as Excel often switches dates to a MM/DD/YY format, I often had to reformat dates manually into a YYYY-MM-DD style.

- In order to generate geospatial coordinates for place names, I used the free online program “GPS Visualizer” which enables users to generate latitude and longitude information from an address, i.e. “Kassel, Germany.” Similar to the incomplete date information above, another potential drawback of my translation is that it, for consistency and simplicity, replaces the occasional stipulation of a specific address with the geographic centers of cities, such as “Berlin” or “Leipzig.”

- Finally, I cleaned up orthographical errors missed by OpenRefine and other seemingly obvious inaccuracies, such as the confluence of the name “Fritzsche, Jenny” and the city “Jerusalem” into “Fritzsche / Jennyrusalem.”[17] Download the final dataset (File 6).

After stage three—plugging the resulting spreadsheet into Palladio—the key question arises: What do the timeline, map, and network graph tell us about the materials in the archive and, hopefully, about Rosenzweig’s intellectual if not also personal biography? What one first gleans from the information provided by Palladio, in particular the timeline, may seem self-evident. Most of the documents fall in the early years of the Weimar Republic, with a precipitous drop off around 1930, the year after Rosenzweig’s death (see Figure 8).

According to the map, most of the documents also originate in cities in which Rosenzweig, along with friends and family, lived, worked, and studied (see Figure 9). But what we can glean from the map is that Frankfurt, Kassel, and Göttingen displace Berlin as the center of intellectual activity during the Weimar Republic, at least according to the snapshot offered by Rosenzweig’s archive.

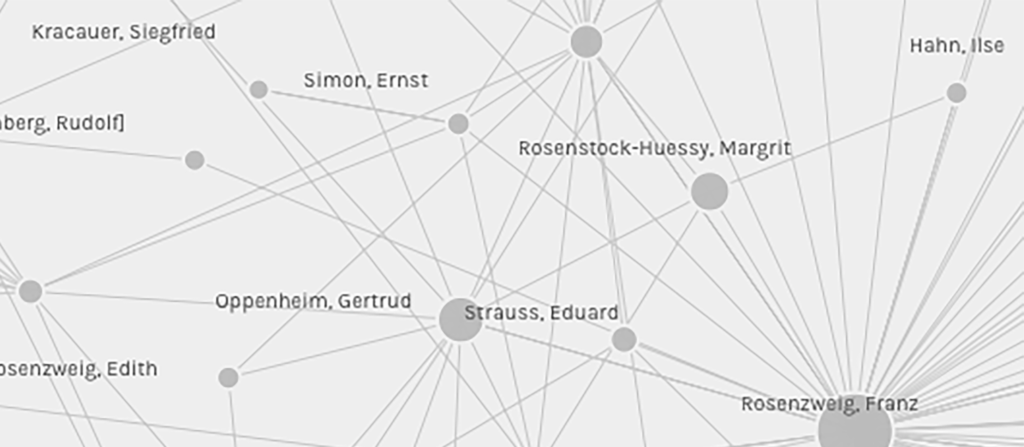

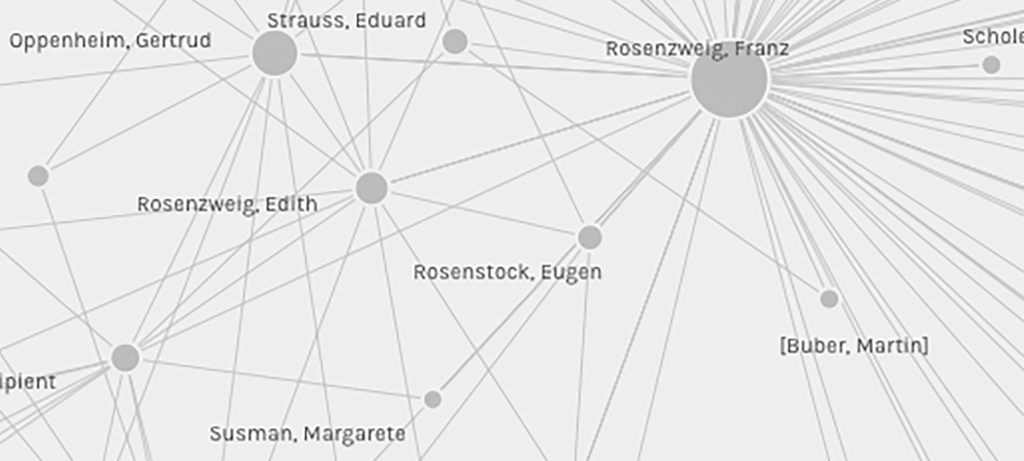

More telling, however, is the network visualization (Figure 10), which offers insights that potentially carry serious consequences for Rosenzweig studies. First, the network visualization reveals significant gaps in the archival metadata as well as the presence of archival additions through the prominence of “Unknown – Author” and “Unknown – Recipient” as well as the doubling of some figures (“[Strauss, Eduard]” and “[Strauss,] Eduard”).[18]

Second, the network visualization indicates the prominence of interlocutors marginalized in the scholarship on Rosenzweig or previously rendered voiceless in his collected works, such as his cousin Gertrud Oppenheim, as in Figure 12, and his wife Edith Rosenzweig.[19]

Finally, the visualization points us to letters neither written nor received by Rosenzweig himself, but rather by his friends, contemporaries, and critics, such as between Simon, Kracauer, or between Oppenheim and numerous correspondents (Figure 13).

Cross-checked in the finding aid, the Simon-Kracauer “edge” (the connecting link between two nodes, see Weingarten) corresponds to four letters sent between Simon and Kracauer in May 1926, shortly after the appearance of Kracauer’s critical review “The Bible in German” of the first installment of Buber and Rosenzweig’s translation of the Hebrew Bible, mentioned above. In more general terms, the act of literally translating the finding aid into a visual medium thus sorts, rearranges, and renders visible potentially significant exchanges and underrepresented voices in the archive that would have been excluded had our focus fallen only on letters to and from Rosenzweig himself. And, in the case of Simon and Kracauer, digital translation also prompts a return to the material archive itself, if not also the philosophical underpinnings of Rosenzweig’s theory of translations and its potential critiques.

3.

Buber and Rosenzweig’s Bible translation crystalizes and radicalizes essential elements of Rosenzweig’s reflections on the subject from 1924, including his emphasis on semantic and syntactic literal translation. And it is precisely the effects of these literal renderings, and their temporal consequences that Kracuaer found linguistically and culturally problematic in 1926. As the controversy is well-documented in the critical literature, it suffices to cover its central dynamic in order to frame what is at stake in Simon and Kracauer’s missives.[20] For Buber and Rosenzweig, their translation peels away layers of Christianizing mediation through Luther’s translation and responds, as Buber puts it, to the fact that “the Hebrew sounds themselves have lost their immediacy for a reader who is no longer a listener” (73). The aesthetic achievement of these cultural goals rests on the attempt to restore the spoken character of the Biblical text, by retaining in German the Hebrew’s rhyme and meter and consistently rendering repetitions of names, words, and other Leitworte. Yet, unlike Rosenzweig’s translation of Halevi, Buber and Rosenzweig’s Bible lacked a critical afterword or apparatus. By preserving and not commenting on the alliteration in the original, Buber and Rosenzweig achieve for Kracauer a language that “is to a great extent archaicizing,” reminiscent of Richard Wagner’s use of an alliterative verse evocative of a Germanic past (195-196). This “anachronistic quality of the translation” produces, for Kracauer, reactionary effects that take “flight from the realm of the ordinary public sphere” (198). The criticism provoked intellectuals from diverse religious and cultural backgrounds, providing the final divide between two diverging discourses on Jewish intellectual secularization in the Weimar Republic: advocates of Jewish renewal (Simon, Margarete Susman, Nahum Glatzer) backing Buber and Rosenzweig and the forerunners of Critical Theory (Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, and Theodor W. Adorno) siding with Kracauer.[21]

We thus witness, in Simon and Kracauer’s letters, the dynamics of this split in microcosm. Indeed, the scholarly record has included this epistolary exchange since Martin Jay’s groundbreaking essay “The Politics of Translation” (1976), which discusses Simon’s challenges to Kracauer and adeptly reconstructs Kracauer’s response.[22] At heart, Simon challenges Kracauer on multiple points relating to what he sees as the latter’s insensitivity or misrepresentation of Buber and Rosenzweig’s philosophical and cultural goals, stating—in terms that well describe Critical Theory—that, when in doubt, Kracauer always erred on the side of the distinctly negative (see 7 May, 1926). Kracauer’s responses, however, not only help clarify his polemics in the translation controversy, but also call into question the ideological underpinnings of Rosenzweig’s theory of translation—and problematize our usage of it for visualization. In them, Kracauer coalesces his criticism around the concepts of intentionality and effect. Countering Simon’s claim that his criticism wrongly ascribes to Buber and Rosenzweig’s translation efforts a “völkisch” objective, Kracauer explains: “one cannot confuse the intention, with which something is undertaken, with the reality of this same thing and its effect. I spoke of the effect, not the intention” (21 May, 1926). Kracauer’s point is delicate, but incisive. As he sees it, he neither wishes to equate Buber and Rosenzweig with the völkisch-Romantic revival of the late nineteenth century, nor state that Buber or Rosenzweig harbor völkisch-nationalistic intentions. Rather, they employ words and literary forms associated with such völkisch tendencies, because, as he writes, “words, too, have their history” (12 May, 1926). Problematic for Kracauer is that the Biblical language achieved in translation and late-nineteenth century neo-Romanticism share the aesthetic undercurrents, naively or purposefully, of “the Saga, the Book, the Bible of a people,” as Hegel put it, “which expresses for it its own original spirit” (1045). Kracauer warns—and many in the digital realm may wish to listen—that an aesthetic object, the mediation of an aesthetic object, and, in contrast, the purported immediacy of an aesthetic object can produce effects and enter into filiations that exceed the intent and control of an author and, all the more, a translator.

To be sure, Kracauer’s criticism of the Buber-Rosenzweig Bible contains many of its own shortcomings, not the least his imprecise language, which seems at points hasty to posit a direct link between Wagner and the translators, or the seeming ill will of his candor, for which Susman and Simon reproach him. But Kracauer’s responses to Simon are instructive in terms not only of the translation controversy, but also current debates in the digital humanities. As we saw with Rosenzweig’s work on Halevi, translation can mediate temporality in a way that reconnects the Biblical past, the omnipotent and omnipresent word of God with those, as Buber puts it, in the modern world willing to hear it (159). In contrast, for Kracauer there is another kind of temporality and timeliness to translation, especially when such translation, namely Buber and Rosenzweig’s Bible, hides its mediating function. Indeed, for Kracauer, the established feuilletonist and film critic of the Frankfurter Zeitung, an aesthetics that minimizes mediation is anathema to a world ever more mediated and saturated by new media, images, and technologies. And precisely this sensitivity to temporality and mediation, to questioning one’s position in and mediation through history, and to an awareness of its patterns and repetitions is what underlies and exemplifies the cultural-critical paradigm that emerges in German-Jewish thinking in the early twentieth century. Beyond, then, simply providing greater access to the historical record, visualizing Rosenzweig’s archive both reveals new information about Rosenzweig’s work on translation and, at the same time, further problematizes it. This duality of revelation and problematization, I submit, is the real promise and threat of the digital humanities as represented by Rosenzweig’s finding aid: revealing archival material only indicates that the core problems of the humanities, such as the relationship between technology and language, remain fundamentally unresolved.

How, then, do German Studies and the digital humanities mutually inform each other? And what is at stake, for scholars of German and German-Jewish Studies as well as the digital humanities, if they do? Most specifically, the digital visualization of Rosenzweig’s archive provides scholars with a basis for further research into marginalized voices in his archive and illuminates new avenues for scholarship examining the debate sparked by Buber and Rosenzweig’s Bible translation and the effects this debate had on German-Jewish intellectual life. In bringing these new perspectives to light along the lines of Rosenzweig’s theory of translation, the visualization paired with further analysis also leads to the entanglement of theory and critique in Jewish intellectual thought in the Weimar Republic. Furthermore, the combination of digital and traditional methods emphasizes, in Rosenzweig and Kracauer’s case, the assumptions and ideological commitments motivating language and translation—indeed, we observe here that there may exist even more elegant and apt techniques for translating data than Rosenzweig’s. What the digital humanities thus helps us see in Rosenzweig’s theory of translation may not be “critical” in the Frankfurt School sense of the word, but his theory of translation is symptomatic of how knowledge is constructed, negotiated, and legitimized in times when the value of traditions, such as humanistic inquiry, are up for debate. Ultimately, what is compelling and timely about Rosenzweig’s writings is not necessarily his work on translation itself, but the enduring idea that there could exist an alternative—a theory of language, critical thinking, and hermeneutics—to the epistemological paradigms of technology and mediation from which the digital humanities, at least in part, stem.

Conversely, at stake in bringing the concepts of translation, cultural criticism, and close and contextualized reading from German Studies into dialogue with the digital humanities is less the validity of Rosenzweig’s or my specific approach to translation, and more the visibility and benefit of further discussion. Rosenzweig’s theory of translation and Kracauer’s critique of it call on us to think clearly and rigorously through the moments of translation underpinning digital humanities work. They also force us to take account of the historical situations to which these acts of translation react, and the ideological commitments in whose service they function—then and now. Yet what Rosenzweig’s theory of translation, if not also German Studies, can reveal to the digital humanities more generally is that new inquiry aided by digital technologies is not a visual replacement of, but a renewed confrontation with the core principles of our discipline such as lesen and übersetzen. The techniques of selecting, reconfiguring, and transposing language from one medium, time, or format to another—which underpin Rosenzweig’s work on translation and our visualization of his archive—show us how both are concerned with the same intellectual legacy: the problem of and anxiety over a society and a tradition radically transformed by these very same technologies of mediation and language. This is, however, not a story of a return to a once happy union. Instead, tasks such as visualizing Rosenzweig’s archive reinstate and remind us of the intellectual tensions between what we have come to consider technology, different forms of mediation, and the humanities which have separated our disciplines and indeed our ideological outlooks on the world for decades. Hence, insisting on a tenuous yet critically productive and conscious entwinement of technology, mediation, and the humanities is perhaps the very contribution that German Studies can make to the digital humanities.

Works Cited

“The Annotated Star | A Digital Edition of Franz Rosenzweig’s STAR OF REDEMPTION.” http://www.annotatedstar.org. Online. July 20 2015.

“Archives Department.” The National Library of Israel. http://web.nli.org.il/sites/NLI/English/collections/personalsites/Pages/default.aspx. Online. July 20 2015.

Batnitzky, Leora. Idolatry and Representation: The Philosophy of Franz Rosenzweig Reconsidered. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000. Print.

Belke, Ingrid. “Siegfried Kracauer: Geschichte einer Begegnung.” Grenzgänge zwischen Dichtung, Philosophie und Kulturkritik: Über Margarete Susman. Eds. Anke Gilleir and Barbara Hahn. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2012. 35-61. Print.

Benjamin, Mara. Rosenzweig’s Bible: Reinventing Scripture for Jewish Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. Print.

Bowker, Geoffrey C. Memory Practices in the Sciences. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005. Print.

Bowker, Geoffrey C. and Susan Leigh Star. Sorting Things Out: Classification and its Consequences. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000. Print.

Brasser, Martin, ed. Rosenzweig als Leser. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 2004. Print.

————. “Kritik an Islam.” Rosenzweig Jahrbuch. Vol. 2. Freiburg: Karl Alber, 2007. Print.

————.“Paulus und die Politik.” Rosenzweig Jahrbuch. Vol. 4. Freiburg, 2009. Print.

Buber, Martin and Franz Rosenzweig. Scripture and Translation. Trans. Lawrence Rosenwald and Everett Fox. Bloomington: Indian University Press, 1994. Print.

Erlin, Matt and Lynne Tatlock, eds. Distant Readings: Topologies of German Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century. Rochester: Camden House, 2014. Print.

Forster, Michael. “Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2015 Edition). Ed. Edward N. Zalta. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2015/entries/schleiermacher. Online. July 20 2015.

Geitelman, Lisa and Virginia Jackson. “Introduction.” “Raw Data” is an Oxymoron. Ed. Lisa Gitelman. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013. Print.

“Glatzer Collection and Archives.” Jean and Alexander Library, Vanderbilt University. http://www.library.vanderbilt.edu/divinity/services/glatzer.php. Online. July 20 2015.

“GPS Visualizer.” http://www.gpsvisualizer.com/geocoder/. Online. July 20 2015.

“Guide to the Papers of Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929), 1832-1999” http://findingaids.cjh.org/?pID=121441. Online. July 20 2015.

Jacobs, Jack. The Frankfurt School, Jewish Lives, and Antisemitism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. Print.

Jay, Martin. “The Politics of Translation: Siegfried Kracauer and Walter Benjamin on the Buber-Rosenzweig Bible.” Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook. 21.1 (1976): 3-24. Print.

Jockers, Matthew. Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013. Print.

Kirsch, Adam. “Technology Is Taking Over English Departments: The False Promise of the Digital Humanities.” New Republic. May 2, 2014. https://newrepublic.com/article/117428/limits-digital-humanities-adam-kirsch. Online. 26 November 2015.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “The Bible in German.” The Mass Ornament. Trans. Tom Y. Levine. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. 189-203. Print.

————. Letter to Ernst Simon. 12 May 1926. Universitätsbibliothek-Landesbibliothek and Murhardsche Bibliothek of the City Kassel. Signature: 2° Ms. philos. 39 Box F1, Document 2.

————. Letter to Ernst Simon. 21 May 1926. Universitätsbibliothek-Landesbibliothek and Murhardsche Bibliothek of the City Kassel. Signature: 2° Ms. philos. 39 39 Box F1, Document 3.

Lesch, Martina and Walter Lesch. “Verbindungen zu einer anderen Frankfurter Schule. Zu Kracauers Auseinandersetzung mit Bubers und Rosenzweigs Bibelübersetzung.” Siegfried Kracauer: Neue Interpretationen. Eds. Thomas Y. Levine and Michael Kessler. Tübingen: Stauffenberg, 1990. 171-193. Print.

Hegel, G. W. F. Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art. Vol. 2, Trans. T.M. Knox. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975. Print.

“OpenRefine.” http://openrefine.org. Online. July 20 2015.

Padilla, Thomas. “Getting Started with OpenRefine.” http://thomaspadilla.org/dataprep/. Online. July 20 2015.

“Palladio.” Humanities + Design: a Research Lab at Stanford University. http://palladio.designhumanities.org. Online. July 20 2015.

Pollock, Benjamin. “Franz Rosenzweig.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2015 Edition). Ed. Edward N. Zalta. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2015/entries/rosenzweig/. Online. July 20 2015.

————. Franz Rosenzweig’s Conversions. World Denial and World Redemption. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014. Print.

Rooney, Ellen and Elizabeth Weed, Eds. In the Shadow of the Digital Humanities. Special issue of differences 25.1 (2014). Print.

Rosenzweig, Franz. “Afterword” and “Notes.” Franz Rosenzweig and Jehuda Havel: Translating, Translations, and Translators. Trans. and Ed. Barbara Ellen Galli. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995. Print.

————. Feldpostbriefe: Die Korresponden mit den Eltern (1914-1917). Ed. Wolfgang D. Herzfeld. Freiburg: Karl Alber, 2013. Print.

————. Der Mensch und sein Werk: Briefe und Tagebücher. Vol. 1.2, Eds. Rachel Rosenzweig and Edith Rosenzweig-Scheinmann. Haag: Nijhoff, 1979. Print.

————. Der Mensch und Sein Werk. Vol. 4/1, Ed. Rafael Rosenzweig. Haag: Nijhoff, 1983. Print.

————. “Nachwort” and “Bemerkungen.” Jehuda Halevi: Zweiundneunzig Hymnen und Gedichte. 2nd ed. Berlin: Lambert Schneider, 1927. Print.

“Rosenzweig | Projekte.” Internationale Rosenzweig Gesellschaft, e.V. http://www.rosenzweig-gesellschaft.org/projekte/. Online. July 20 2015.

Rosenwald, Lawrence. “On the Reception of Buber and Rosenzweig’s Bible.” Prooftexts 14.2 (May 1994): 141-165. Print.

Simon, Ernst. Letter to Siegfried Kracauer. 7 May 1926. Universitätsbibliothek-Landesbibliothek and Murhardsche Bibliothek of the City Kassel. Signature: 2° Ms. philos. 39 Box F1, Document 1.

“Tabula: Extract Tables from PDFs.” http://tabula.technology. Online. July 20 2015.

“Teilnachlass Franz Rosenzweig Kurzliste.” Universität Kassel. http://www.uni-kassel.de/ub/fileadmin/datas/ub/dokumente/handschriftenabteilung/Wahle_Teilnachlass_Franz_Rosenzweig.pdf. Online. July 20 2015.

Venuti, Lawerence. The Translator’s Invisibility. A History of Translation. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2008. Print.

Weingarten, Scott B. “Demystifying Networks, Parts I & II.” Journal of the Digital Humanities. 1.1 (2011). http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-1/demystifying-networks-by-scott-weingart/ Online. July 20 2015.

[1] The finding aid, “Teilnachlass Franz Rosenzweig Kurzliste,” is available online. Silke E. Wahle developed it along with “Auswertung der Bestandaufnahme der Teilnachlässe von Franz Rosenzweig und Rudolf Ehrenberg” in February 2007; both items unpublished. According to Pfeil, Director of Special Collections at the University Library in Kassel, a further refined and revised iteration of the finding aid is forthcoming.

[2] The University purchased the documents from Rosenzweig’s daughter-in-law, Ursula Rosenzweig. For more information regarding the purchase, see “Rosenzweig | Projekte.”

[3] For Rosenzweig’s near conversion to Christianity and the academic myth surrounding it, see Pollock Franz Rosenzweig’s Conversions, especially the introduction and Chapters 1 and 3; for an overview of Rosenzweig’s translation project, see Benjamin, Chapters 2 and 3.

[4] See articles such as Kirsch and recent special journal issues such as Rooney and Weed.

[5] See contributions to Brasser, Rosenzweig als Leser, “Paulus und die Politik,” and “Kritik an Islam.”

[6] For more information on these projects, see “The Annotated Star | A Digital Edition of Franz Rosenzweig’s STAR OF REDEMPTION.” Other Rosenzweig-related archival holdings can be accessed online through “Guide to the Papers of Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929), 1832-1999” (holdings at the Leo Baeck Institute, NYC), Rosenzweig’s papers in “Glatzer Collection and Archives” (Nahum Glatzer’s archive at Vanderbilt), and in Martin Buber’s papers, “Archives Department,” (National Library of Israel).

[7] Cf. Benjamin; Batnitzky, 105-142.

[8] See the essays in Erlin and Tatlock.

[9] Regarding the latter, see Jockers; in the context of German Studies, see Erlin and Tatlock.

[10] On the question of “raw data” and data standards in the sciences, see Bowker, 183-184 and Bowker and Star.

[11] Buber collected and published these essays first as Die Schrift und ihre Verdeutschung in 1936, see Buber, “Scripture and Translation.” Important, at least as we will see for Kracauer, is that these essays were not published as part of the Bible translation itself.

[12] For an overview of Star of Redemption, see Pollock, “Franz Rosenzweig.”

[13] On Schleiermacher, see Forster.

[14] Henceforth, “metadata” refers to the information in the finding aid as it pertains specifically to the archive and “data” to the “metadata” after it has been transformed via extraction, refinement, or visualization. As Palladio “only” reads and visualizes the data from the CSV file without changing their values, it is in Tabula and OpenRefine that the most major manipulations of the data take place. In extracting the data tables from the PDF, Tabula often, for instance, transposes, adds, or subtracts characters and spaces from the original finding aid. With OpenRefine, users directly manipulate the values of the dataset by choosing to collate similar data values or names and, potentially, by removing excess characters such as parenthesis or brackets. What modifications these programs enact on the level of code and algorithm is an interesting question for further study, but beyond the scope of this study.

[15] As Wahle explains: “B” corresponds to letters; “W” to works, manuscripts, and typescripts; “L” to biographical documents and photographs; and “S” to collections, which include newspaper clippings and smaller publications from those surrounding the Rosenzweig family.

[16] See Thomas Padilla’s extremely helpful guide “Getting Started with OpenRefine.”

[17] Jenny Fritzsche was a personal friend of the Rosenzweigs and the wife of Robert Arnold Fritzsche, a librarian and acquaintance of Hermann Cohen (see Rosenzweig, Der Mensch und sein Werk 1121). The error could have arisen as a spreadsheet program originally completed characters entered as “Je-” (the origin of Gershom Scholem’s letters to Rosenzweig in files A43 and A44) with information previously entered for Fritzsche’s letter to Rosenzweig in A12.I aantenceedeal, I readers more igs and ” that it lar problem and weakness in translation. Although not ideal, I readers more

[18] Another noteworthy aspect of my translation is that the practice of replacing missing information about authors or recipients with the same string, i.e. “Unknown – Author,” amalgamates all unknown authors in the visualization into a single node.

[19] Recent archival work by Wolfgang D. Herzfeld on Rosenzweig’s Feldpostbriefe takes an important editorial step in including the letters of Rosenzweig’s mother, Adele, in publication.

[20] See articles by Jay, Lesch and Lesch, and Rosenwald.

[21] See Jay’s account of Benjamin and Adorno’s reaction, 19-24 as well as Ingrid Belke’s account of Susman and Kracauer’s relationship.

[22] Jay, 16-17. See also Jacobs 25-27 and 167n131.