Animals in Architecture

by Sabine Scho

TRANSIT vol. 12, no. 1

Translated by Bradley A. Schmidt

Translator’s Introduction

Sabine Scho’s work is hard to pin down. The German publisher of Animals in Architecture—Kookbooks—is largely dedicated to contemporary poetry, perhaps leading one to an over-hasty taxonomy. Upon closer inspection, Scho’s work, in particular Animals in Architecture, is a hybrid combining prose miniatures, poetry translations and fragments, sociological reflections, and photos with a green color filter. Indeed, Scho’s work on this project first started with photography, spanning nearly a decade of visiting zoos across the globe. In 2012, she started a blog as a kind of accountability mechanism for finishing the book. However, there remained questions of form, content, even language. Largely written while living in São Paulo, Animals in Architecture contains many traces of Anglophone and Portuguese influence.

In each of the book’s twenty-two sections, Scho closes in on animals, whether camels, bats, penguins, or octopus. A quote from Hans Blumenberg is one of the two epigraphs to her introductory essay—aptly describing a central paradox of zoos: the relationships between the animals in the enclosures and the homo sapiens outside. Many of her poems remind us that it is often unclear who is watching whom. John Berger’s essay “Why Look at Animals?” notes that zoos are simultaneously a “living monument” to the disappearance of caged creatures from our culture. People go to zoos to see animals, but it is unlikely that the animals want to see humans. Animals in Architecture documents an attempt to reconnect with these animals and its ultimate futility.

Although I try to keep a close watch on the contemporary German poetry scene and had come across some of Sabine Scho’s work before Animals in Architecture was published in 2013, I was quite surprised by this work’s genre-bending mix of elements. In the following year, I tried my hand at translating these challenging texts and managed to place a couple poems in No Man’s Land, an online journal dedicated to publishing German literature in English translation.

Scho’s regard has only increased in current German-language discourse. In particular, the significance of her contributions to debates on human relations with the environment have continued to grow; she was recognized with the Deutscher Preis für Nature Writing alongside the poet Christian Lehnert in the summer of 2018. The following essay is among the most concise German-language takes on the subject of zoos, animals, humans, and the ways in which architecture exemplifies our fraught relationship.

Translation

Animals in Architecture

Humans are animals who keep other animals. First as pets, then much later as exhibits.

– Hans Blumenberg

One forms an image of a man’s nature and character according to his place of residence and the neighborhood he inhabits, and that is exactly what I did with the animals of the Zoological Garden.

– Walter Benjamin

Zoological gardens are interfaces that bear witness to the lives of every other species. Their design reflects the self-understanding of a society that constantly redefines its place in evolution.

A visit to the zoo today no longer requires an image of symbolic order, as it was still embodied by Louis XIV’s menagerie. His architect, Louis Le Vau, arranged the enclosures into so-called lodges. Corresponding to the concept of absolute rule, he organized them concentrically from the perspective of the Sun King.

Animal-appropriate enclosures built today provide more than constructed hegemony. It is not positivistic thirst for education that drives us. Rather, we search for reservations of longing in the backdrops of landscape. Correspondingly, the zoo project has been inverted as it were: we artificially rebuild in detail what we destroy en masse. Large open areas replace individual enclosures and collect biotic communities from the most varied climate zones.

The US trailblazes with the realization of such geographic spaces. In the San Diego Zoo, visitors float in the “cage,” the aerial tram, over strange imitation landscapes and become acquainted with the park from a bird’s eye view.

On the Monterey Bay near San Francisco and in Long Beach by Los Angeles exist two examples of what is likely the most popular type of architecture for animals: aquariums. These days they have become representative structures by star architects. Frank O. Gehry, for example, designed the Aquarium of the Pacific for Long Beach. There was an emphasis here on a particular aesthetic added value, using architecture to stage the multicolored sea dwellers as living dioramas. The need for making contact was also factored in: shark and ray touch pools are state of the art and shouldn’t be absent from any aquarium today.

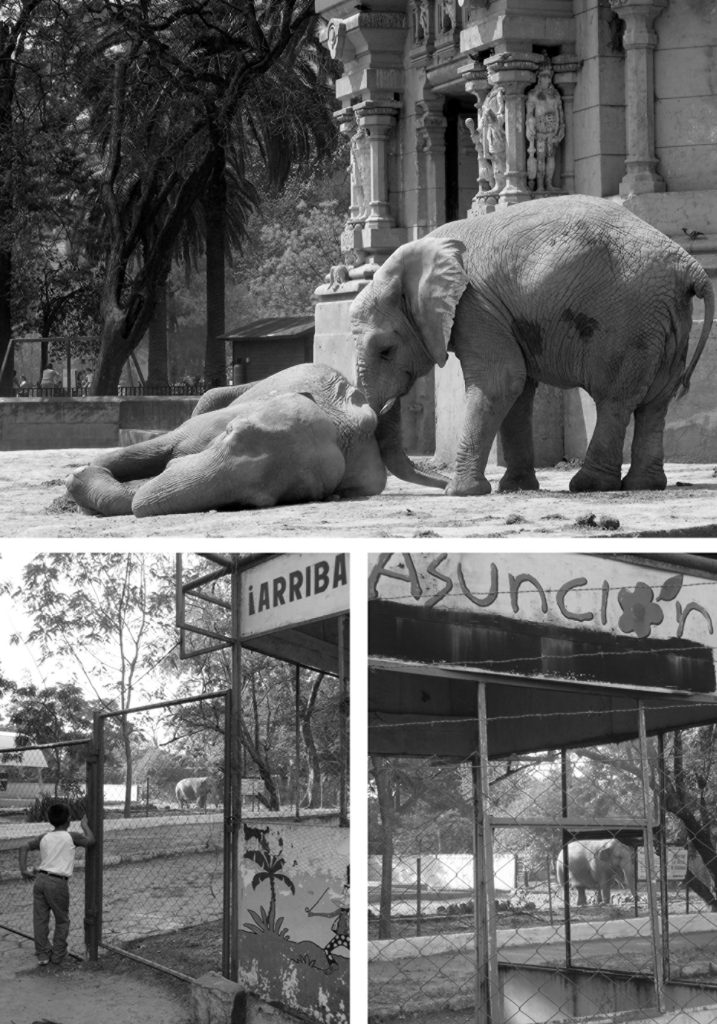

Even the most perfect of natural simulations cannot hide the fact that zoos—regardless of their emphasis on conservation and education—have produced entertainment architecture. In addition to providing mutual protection for animals and audience, they demand optimal visuals and proximity. No zoo in the world can afford to have its animals completely retreat from human gaze, whether through replicating nature or making cages to resemble constructivist stages (such as those designed by Berthold Lubetkin in the 1930s for London’s Regent Park and the Dudley Zoo near Birmingham, or Carl James Bühring’s work for the Leipzig Zoo in 1926, inspired by brick expressionism). And today bars need no longer serve as barriers when water or dry ditches can appear as natural obstacles.

The concept of open enclosures is not so new when one thinks of Carl Hagenbeck and his utopia of a zoo without bars—realized in Stellingen near Hamburg in 1907. Hagenbeck, who got his start as a fishmonger in the St. Pauli neighborhood of Hamburg, earned his money as an animal dealer, touring across the world with his infamous ethnological expositions, as well as his circus and portable panoramas. He had quickly grasped the essential element of the entertainment enterprises that were 20th century zoos: Edenic conditions.

Yet what comes together to form a seemingly coherent image starts with an imitation mountain ridge and ends with a Japanese garden, corresponding completely with the model of a landscape pastiche.

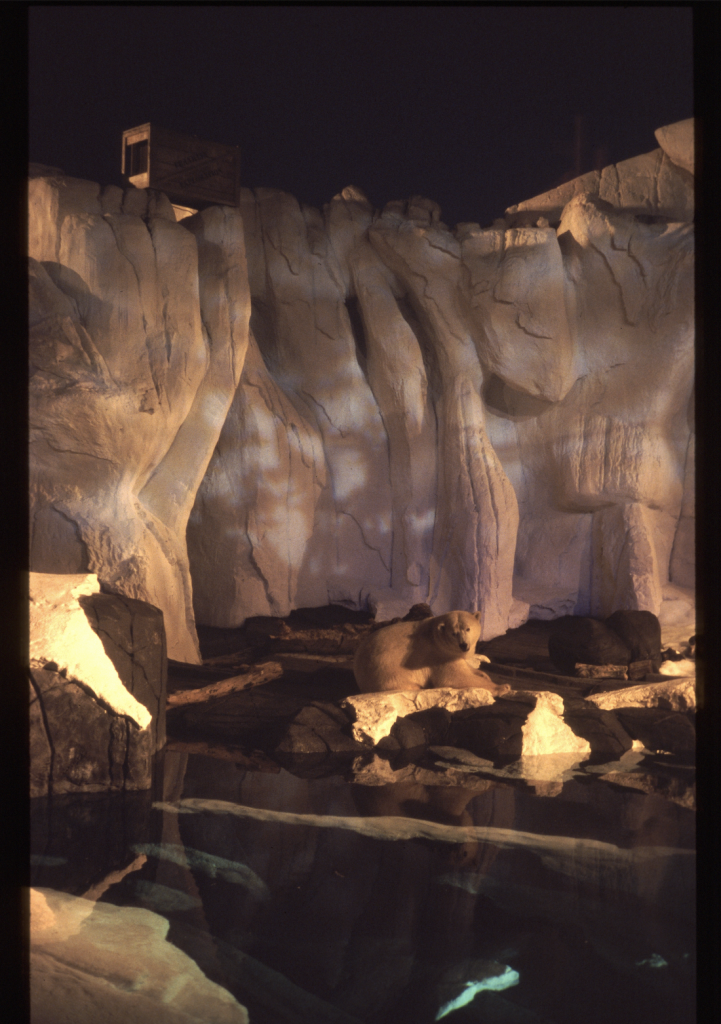

No seamless transitions exist in zoos: Rain forests are located directly next to cold storage units for animals with glacial ambiance. One can walk through swinging doors to pass from maritime touch pools into an arid desert, reversing the daily rhythm of nocturnal animals, shrouding visitors in a midday darkness. A zoo not only draws its lines between humans and animals, typically, it also draws one between the animals as well. Natural enemies ultimately disrupt the image of a zoo as paradise which, unlike in Ancient Rome, should not also be a battle arena.

Menageries are theatrical places, no less than theaters, churches, temples, arenas, or mausoleums. A defined course, calculated perspectives, vistas, viewing platforms: all of this is still taken into account in the exposition architecture of zoos.

Legendary zoological gardens include the Ammon’s Garden in Thebes of Pharaoh Hatshepsut who kept waterbucks, antelopes, gazelles, ostriches, giraffes, and elephants in 1450 BCE.

It is hardly imaginable, but Wen Wang, Emperor of China, had already constructed the Garden of Intelligence around 1000 BCE. The animal reserve’s collections included mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, and the Milu—a kind of deer that had already become extinct in its natural habitat.

With these first zoos, they were already practicing what would only be conceptualized much later: Globalization. Exotic animals have always been among the gifts of kings and queens, serving a representative role, and thus even Noah had no need to travel the whole world to load the animals onto his zoo boat.

Today, one still hopes to derive representative meaning, thus MGM keeps a small population of symbolic animals behind glass in the casino halls of its hotel in Las Vegas.

An international style has been realized by zoos and aquariums which was already familiar from hotel and restaurant chains (SeaWorld Adventure Parks, Bush Gardens, Sea Life Centres). Individualized enclosure solutions are increasingly hard to find. Once past the ticket office, architecture is hidden and nature simulated. But even the giraffe in the Santa Barbara Zoo looks out onto the freeway from its enclosure. One could almost believe that the hereditary crook in its neck comes only from the fact that it would like nothing more than to slip past the artificial cliffs, dreaming of the fluid spaces of a global society which—with its natural, free spaces—has succeeded more in hoodwinking itself than the giraffe. Or is it listening to hidden loudspeakers? Wherever the staging of savanna landscape and rain forest fails to convince optically, people have long been helped by corresponding soundscapes. Sound designs are the latest trend. And the catch is (as it has always been for set pieces): they need not guarantee authenticity; they only present what doesn’t have to be. The mere possibility that the wilderness could sound this way suffices completely, even if it actually sounds different. In addition to gurgling and bubbling sounds, aquariums play whale song and meditative music for the illusion of a place of artificial rapture and exotic.

It was not uncommon that inns were the first collecting points for animal sales and the foundation for later zoological gardens (Leipzig, Amsterdam). Zoos were founded where animals were easy to transport—near train stations and ports (Berlin, Antwerp, Sydney).

However, the original backdrop for every menagerie remains the enclosed garden, the hortus conclusus: refuge, gardens of pleasure and paradise.

Zoos remain a fractured landscape, at once subtly and disruptively sensational. The staging of a human yearning embedded in the very urbanity it seeks to repress—even though these same urban spaces facilitate a zoo’s existence in the first place. Today, zoos ultimately compete with the open ranges at the edges of our urban centers which have long stood in competition with traditional habitats for the last free-roaming animals in the wild.